The new album of the iconic South African guitarist has just been released on the French label Komos. It’s a tribute to his spiritual ancestors that he told our correspondent Tseliso Monaheng about. Meeting in Pretoria (Tshwane).

There’s a small shopping complex named Kilnerpark Galleries in the Kilnerpark, Pretoria suburb where the troubadour guitarist Sibusile Xaba currently resides. Two doors down from it is the liquor store, currently closed due to the city of Tshwane’s liquor by-law which states that no liquor establishments shall operate beyond a certain time on Sundays.

I arrive in the afternoon and proceed to find a seat in the hangout area/communal cafeteria. This I do after calling Sibusile’s phone, to no avail, to let him know that I’ve arrived for our interview appointment.

A group of men whose eyes are affixed onto the TV set sit a few seats away from me. They are watching a match on television — a Premier Soccer League fixture between the billionaire Patrice Motsepe’s Sundowns, who currently occupy the third position on the score table, and SuperSport United, currently fourth.

A quick scroll down my Twitter timeline, and I land upon a tweet describing the match as “Like watching paint dry”. I dissociate from my environment, eavesdropping momentarily to hear if the situation changes.

I call Sibusile’s phone again. No response. I send a text informing him that I’m in his section, and continue waiting.

Sibusile’s music was a source of great inspiration even before his debut double-LP titled Unlearning/Open Letter to Adoniah, got released by the Joburg-based Mushroom Hour label in 2017. He is from Newcastle in the KwaZulu-Natal province, but might as well call Pretoria his revolutionary home. He’d been active on the innovative live music scene in his adopted city before going solo — initially as a member of the bands Green Orange and Four Seasons, and would also serve as a member in projects by the likes of Tumi Mogorosi (Project Elo, 2014) and Nono Nkoane (True Call, 2015).

His follow-up record, forthcoming on the Paris-based Komos label, is named Ngiwu Shwabada. The title recalls bra Ndikho Xaba, who elevated unto other planes in 2019, at first glance. Film director Nhlanhla Masondo’s Shwabada (2016) is a film about bra Ndikho’s great sonic innovations in the free jazz movement.

Ngiwu Shwabada is a grueling listen, and that has nothing to do with its length. It, like its predecessor, demands attention, patience, and an openness to being challenged, getting disfigured, and having those split pieces glued back together, note-for-note.

Naturally, Shwabada is where our conversation shall begin when he eventually emerges from the doldrums of this mostly Afrikaner suburb.

Pretoria is one of the last bastions of Afrikaner nationalism. It’s one of the dorpies where being black can literally get you killed. It’s also home to a great music heritage, and an even greater history of black resistance. Mamelodi, located eastwards, is where Sibusile’s mentor and spiritual guide Phillip Tabane resided until he also passed away in 2018. It’s clear that Sibusile and his peers — Thabang Tabane, with whom he regularly plays; Azah Mpago; Tumi Mogorosi — are the ones entrusted to advance the mantle of their forebears.

Sibusile Xaba et Thabang Tabane

“My emphasis in my existence, and in the gift that I’ve been given, is this idea of Umdali, the Creator. Ancestry is beautiful because it’s history. But when I’m gone, I will not consider myself an ancestor,” says Sibusile.

A slight miscommunication about time led to a decision to meet the next day. I find him at home in the afternoon, among the fresh produce of his garden and a plate full of assorted fruit that he offers me, and occasionally takes from himself throughout our conversation.

“The acknowledgement I will want my kids is [for them to] give to the Creator, that they created me to leave history behind. Everything goes back to that idea of the creator. The homage with Ngiwu Shwabada is that; I’m saying thank you for giving me a granddad like that, an aunt like this, my late father, the connection with the side of my mom when [she] decided to commit myself to the Xaba/Shwabada lineage. It’s me giving thanks on that level,” he continues.

“The album, everything it’s talking about, [is centred around] remembering. How did we interpret the meaning of existence as Africans? One of my teachers talks about why don’t lions get sick, unless they interact with man-made conditions? Generally, they don’t, because they have stayed true to their design, their way of living. Same with these birds here; have you ever taken a bird to a clinic? Unless it drank water that’s been polluted by man, or eaten something that’s unnatural? That’s what I’m digging into. We’ve been given infinite life. I narrow it down to my immediate surroundings, like my family,” he says.

And by family, he means both his wife, daughter, and the baby they’re expecting; and his extended community of artist-creatives who spill into the worlds of fine art, photography, dance, and the wider arts administration collectives he associates with through the work he does via Capital Arts.

As he heads into the next phase of his career, with promises of bigger tours, venues, and so forth, I ask him to reflect on the impact of his maiden offering.

“Open Letter changed my approach to music. It was like yo, okay this is composition, but it had more purpose than [just] sounding nice. The whole philosophy of approaching the music was evident. It’s what you do when you’re not playing that gives you a voice and gives you a sound. It’s outside this; giving interviews, going on tours — it’s the other side. If you’re an artist, it works like that. If you’re an entertainer, it works differently, because you have to be out and about, you have to really care, you just have to entertain,” he states.

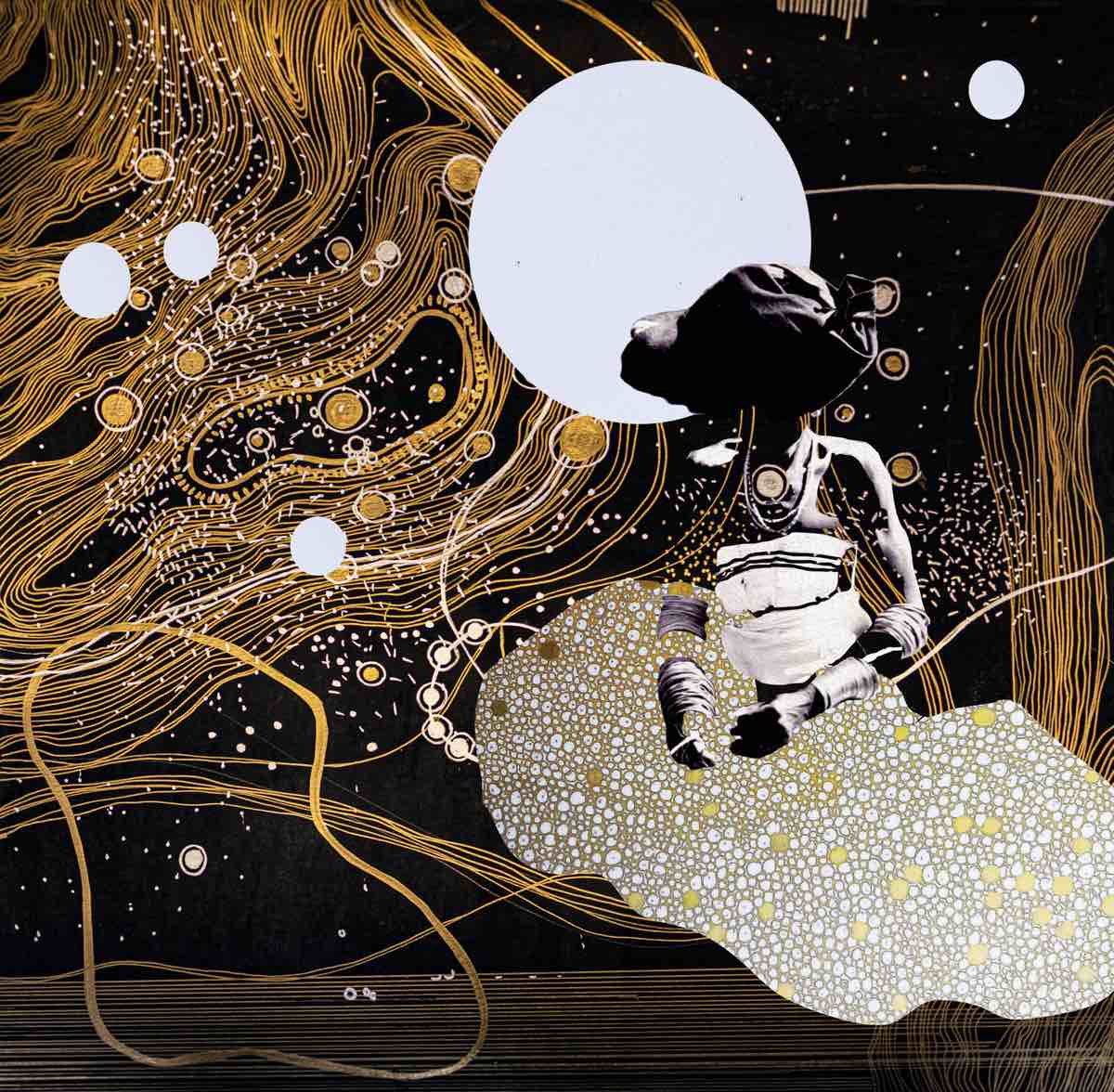

Confining Ngiwu Shwabada to genre is limiting, and shuts down ways in which it can be heard. This music is not one thing. And if we must, we shall refer to it as dream state sonics. With vocal sparring partner Naftali by his side, and the legendary Studio Pigalle studios as their forte, Sibusile sketches soundscapes for the worlds he encounters through the visitations in his dreams. It’s ancestral release, primal by design, and informed by a boundless love — for black people, for the earth from which we came, for the lineage he’s from, and for the wisdom he hopes to impart by the time his next appointment with umdali, the creator, comes.

You can listen Ngiwu Shwabada via Komos here.

- « bra » est une variation de « bro » pour « brother », héritée de « broer » en langue afrikaans