Rumba as a bridge between Africa and Northern America via the Caribbean: ÌFÉ is the musical and spiritual project of the Afro-American DJ, producer, percussionist and composer Otura Mun, born Mark Underwood in the US, and turned priest of the Yoruba’s religion Ifá when he settled in Puerto Rico 18 years ago. If it’s not electronic rumba they’re playing, could it be post-rumba then?

July 2017. It’s 8.30 in Sines, Portugal. The sun still lazily occupies the horizon above the sea, and will light the sky for another hour. Five musicians dressed in white minimalist clothes appear on the “beach stage” of FMM Festival, facing the ocean [read our report of the festival here]. They sit behind white sheets that cover acoustic percussions and electronic machines. “And breathe in… And let it out! Raaah! One, two, three…” and then enter handclaps, synth blips, drum beats, and five voices harmonizing around repeated lyrics. The rhythm clearly sounds as cuban traditional music, and for the specialist, it has this rumba feeling you can’t miss, provided by the specific 2-3 clave: ta-ta… ta, ta-ta. Still, the electronic sounds and a few added percussions change the feeling from time to time, thus appealing the music both to rumba fans and to r’n’b lovers. Lyrics in English, Spanish and Yoruba add a large scope of emotions and levels of understanding. And the sunset on the Atlantic Ocean just makes the whole show a deep and sweet travel to the Caribbean.

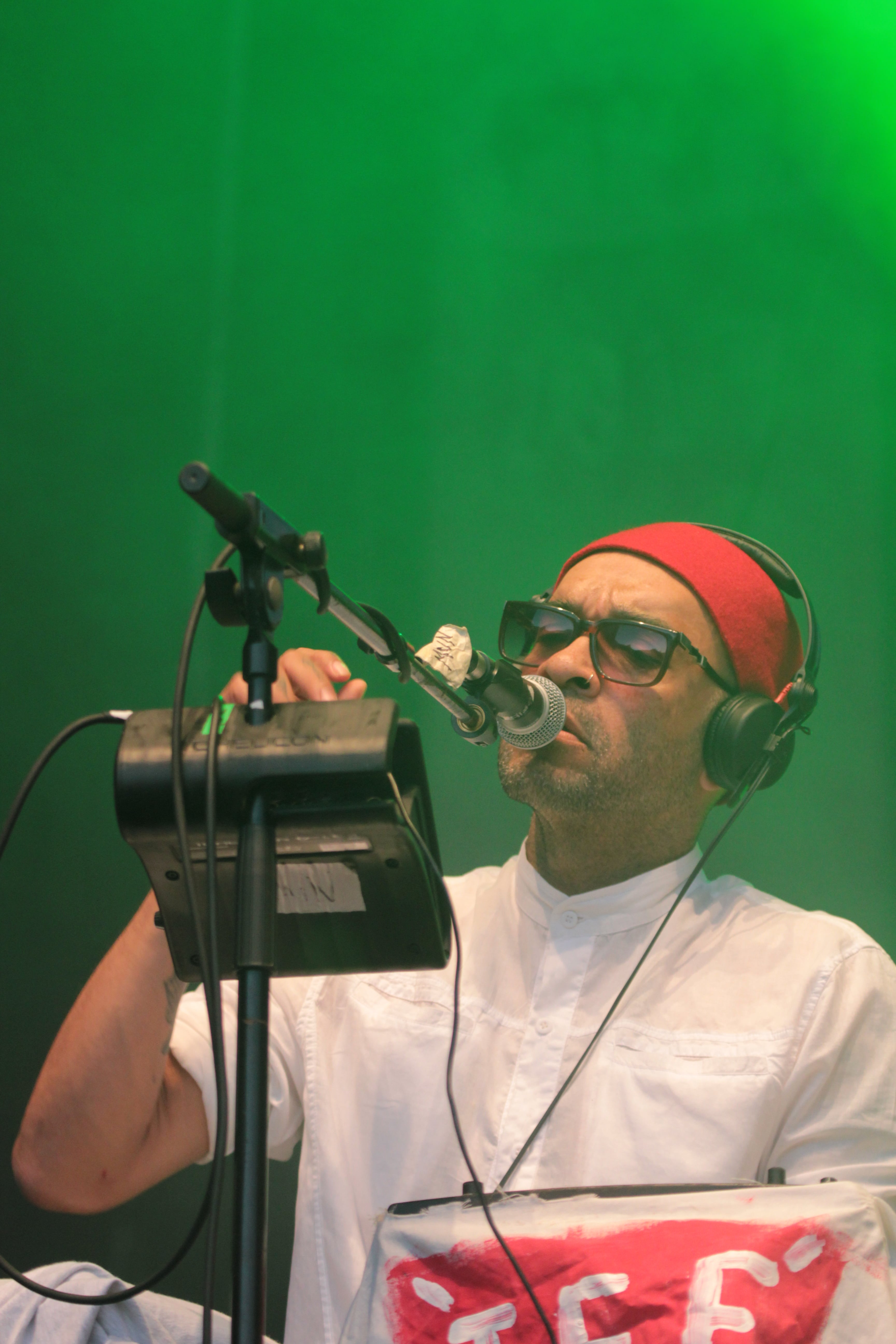

Three hours earlier, we had a chat with ÌFÉ‘s main man, Otura Mun, in the backstage after soundcheck. He gave us a deep and detailed insight into his own mix of Cuban rumba, dancehall, r’n’b and Yoruba spirituality. ÌFÉ is the Yoruban word for “Love” and for “Expansion”.

In Puerto Rico, you became a babalawo priest. Can you tell us about the way spirituality enters your compositions?

Otura Mun: What you hear on the album, lyrics-wise, is me going through changes in the way I understand the world from a different perspective. Seven years ago I was starting to be into yoruba religion where the sacred pieces are stones you need to pray to. But I couldn’t see a stone having life and I couldn’t pray to a rock! A friend of mine told me: “why not?” This very simple answer just convinced me! This chair I’m sitting in could be expressing itself right now. I understood that things could be different from what I thought they were.

I also try to write lyrics that have various levels of engagement, like on the song “Umbo (Come Down)”: the drums themselves are playing a pattern for an orisha called Olokun, during the whole song. You don’t have to sing because the drums are already talking about this orisha that lives in the bottom of the ocean. So when I heard the rhythm I tried to imagine what it would be like if I was diving into the ocean and sink to a medium point where I could see the light refracted from above and the deepness of the ocean below. To me, that mid-way point is like the mid-way point between Heaven and Earth in the idea of spiritual position. The drumming’s purpose is to bring the spirit to the ground so we can communicate with them. This point symbolizes the moment when you are in the moment of need and you need one particular person to help you get to this next place, whether it is your girlfriend, best buddy, or father… So in this song I wrote the lyrics “Umbo, come down, come down, only your love can turn me round, I feel you all around” where “umbo” is Yoruba for “bringing down”. I’m asking the spirit to come down. Someone who doesn’t understand the orisha practice is just hearing me acknowledging the fact that I’m needing somebody. And the day you start to know about orishas, you realize the drums were talking to you the whole song! At the same time, I believe that even if you don’t speak Yoruba, Spanish or English, you can still feel what I mean in my music.

How did you end up in Puerto Rico from the US?

I grew up in a small town in the Midwest (Indiana), only 15 000 people. The closest major city was Chicago, about three hours away. The world around that we saw through media was like Fantasyland to me: L.A., New York… I had the same mentality about Caribbean before going there: palm trees, reggae… I did not even know Porto Rico was in the Caribbean! I had a free plane ticket when I was studying in Texas, and as I was really into Jamaican music at the time, I asked the plane company for Jamaica. But they only had Porto Rico. And that’s where life directed me, by chance!

As an African American and US-born person, how was it to travel and settle in a African-Caribbean island? Would you say there is a common culture between the countries of the archipelago? What about the link with Africa?

As an African American, when I thought about my past tracing my history back to Africa, I would always jump directly from the US to West Africa. But living in the Caribbean helped me to understand that my history is really linked to the Caribbean. It has to do with the racial cast system that we’re living within the US: African Americans are Blacks from America, and we don’t think about having brothers and sisters in Brazil, Panama, Cape Verde…

Musically speaking, what was your approach to African-Caribean music?

When I was a young kid, maybe 17, I heard my first Tito Puente album, and I started a Latin percussion group in my high school. Then as a young adult, I got really into reggae. So I was always into both into Caribbean sound both from Spanish-speaking countries and African-Caribbean places.

When you started your first band, that you describe as “Latin percussion band”, have you already had the notion of the existence of Afro-Caribbean culture, or was it more a general “Latin” culture – that sometimes hides the African roots of it?

I had lived in Porto Rico since 1999 and I took a hiatus in 2007 in Texas, where I started DJ dancehall and reggae in African clubs. There are these big Kenyan, Nigerian and Ethiopian communities, and they would come to my dancehall nights. Then through other African DJs, I got into new afro beats. I took that experience back to Porto Rico and realized the similarity between dancehall and new afro beats.

Then in 2010 it happened something important: I was diagnosed with diabetes and I had to stop drinking alcohol. As you know, everybody is into rum in Puerto Rico. So that meant that if I was in a place where the music wasn’t very good and the conversation wasn’t very good, I didn’t have anything to do. So I started looking into being in places where music was really something immersive. I started to listen to more Cuban rumba live – for example, Yubá Iré. There, rumba is a bit like I imagine be-bop was in its days: the audience is a pretty street audience that understands the genre on a very high level intellectually. It’s not just four guys playing drums; the conversations are very complex and it’s there for you if you want to study that. Like if you go see John Coltrane play, you don’t have to know jazz harmony and structures to enjoy it. But if you do know, you gonna understand what he’s doing on a much higher level.

RUMBA HAS A SPIRITUAL SIDE THROUGH POLYRHYTHMS: YOU CAN PLAY THEM ONLY IF YOU’RE ABLE TO HOLD A CENTER WHILE EVERYTHING IS MOVING AROUND YOU.

What made you want to stay in Puerto Rico?

I had always wanted to learn how to play Cuban rumba and I also felt there was something missing in my life on a spiritual level: I wanted to find out what the invisible world was and how to interface with it. I came across the yoruba practice in Puerto Rico right from the start, with people that were playing music for the orishas, that we called santeros and santeras [people who are entitled to work with orishas within the santería after having completed a ceremony]. They were singing in yoruba in Puerto Rico and this language could be understood by Nigerians! “Wow, you sound like my great-grandfather”, once said a great Nigerian drummer. For an African-American, to see that straight line drawn between Caribbean and Africa was so powerful. I had only seen abstractions of Africa before. I knew there was something there for me, and that I had to dedicate myself to this practice. I came back in 2012 and started to study rumba with a teacher, and initiate and consult Ifá [a religion] with Babaláwos [the priests of Ifá].

Those two elements – religion and music – are not necessarily linked, even if rumba has a spiritual side through polyrhythms: you can play them only if you’re able to hold a center while everything is moving around you.

Why did you chose rumba as the main style? Would you say you play a “modernized” version of rumba?

As a drummer, I knew rumba had the complexity I was looking for, both rhythmically and intellectually.

I wanted to make extra smart music that kids would be able to access, beyond what their parents could even understand, like at the time of Dizzie [Gillespie] or John [Coltrane]. The framework is ancient: rumba is at least 100 years old, and the batá music is probably thousands years old. Yet, the sounds in ÌFÉ – that means “Love and expansion” – couldn’t be retro. It had to be newest sounds, even if they sound cheesy because I knew that I was gonna use them in a way they’re not used yet.

So i’m mixing those ancient genres with dancehall and afro beats, where you have the beats 2 and 4 – and sometimes only the 4 like in dancehall. And as rumba will never give you those 2 and 4, I took that 4 beat – which is a very American thing – and brought it into rumba. You can hear it on “Miami Vice” by Vybz Kartel, and on one of my songs, “House of Love”.

Now I’ll never sing as a rumbero because I didn’t grow up in Cuba singing that stuff, so I’m closer to dancehall which I’ve listened a lot for the last 20 years, and r’n’b – things like D’Angelo. I just put those things together both by choice and by happenstance: I guess there are not that many people who like dancehall and speak Spanish and love rumba as much as I do.

You’re focussing essentially on rumba. As a drummer, are you interested in other percussion-based genres that the African slaves invented in the West Indies, like gwoka in Guadalupe or bèlè in Martinique?

I’m interested in other genres, but I just don’t know them yet. I came across rumba through the drummers I know in Porto Rico and it’s a very demanding music. It’s only 4 years that I’ve been playing rumba, and I’m not that good at it, but I’m touring the world doing that. And even if I know I’ll never be a master of rumba, I want to learn everything. The Afro-American painter Kerry James Marshall – who had a retrospective at the MET in NYC – said that if you were going to paint and be part of something that’s academically labeled, then you have to know what everyone else has done before you. Even if I’m not playing rumba, or even electronic rumba, most of the people think that’s what I’m doing, so I have to perform on the level of the greats that are touring right now: Pedrito Martinez, Osain del Monte, etc. They’re all masters, and I have to be a master, eventually. And that’s a lifelong commitment I’m ready to do. So right now I don’t have that much space to learn about other genres. It’s kind of daunting, as a musician.

What is your relationship with the African diaspora in the Caribbean and in other places in the world?

Anytime I travel to a new Caribbean island, I know I’m going to bump into something that seems quite familiar. There I’m trying to recontextualize what I thought I already knew about Black American music.

What about the African diaspora in the rest of the world?

Right now I’m touring a lot with the ÌFÉ project, and I’m learning Europe and about the African diaspora in Europe: in Barbès-Rochechouart in Paris, for example.

How is life in Puerto Rico right now?

It’s tough times on the island… Puerto Rico has a huge debt crisis to deal with, politically it’s a mess… As I’m enjoying the privilege that I have to be able to travel, I’m trying to stay as grounded as possible to my brothers and sisters over there. And everywhere I go, all I can see is home: Puerto Rico.

(c) João Barbosa (website)