The English producer at the head of World Circuit Records has played a key role in the large circulation of African and Cuban music in the Western countries. For PAM he revisited his personal history. First milestone: his meeting with the great Ali Farka Touré.

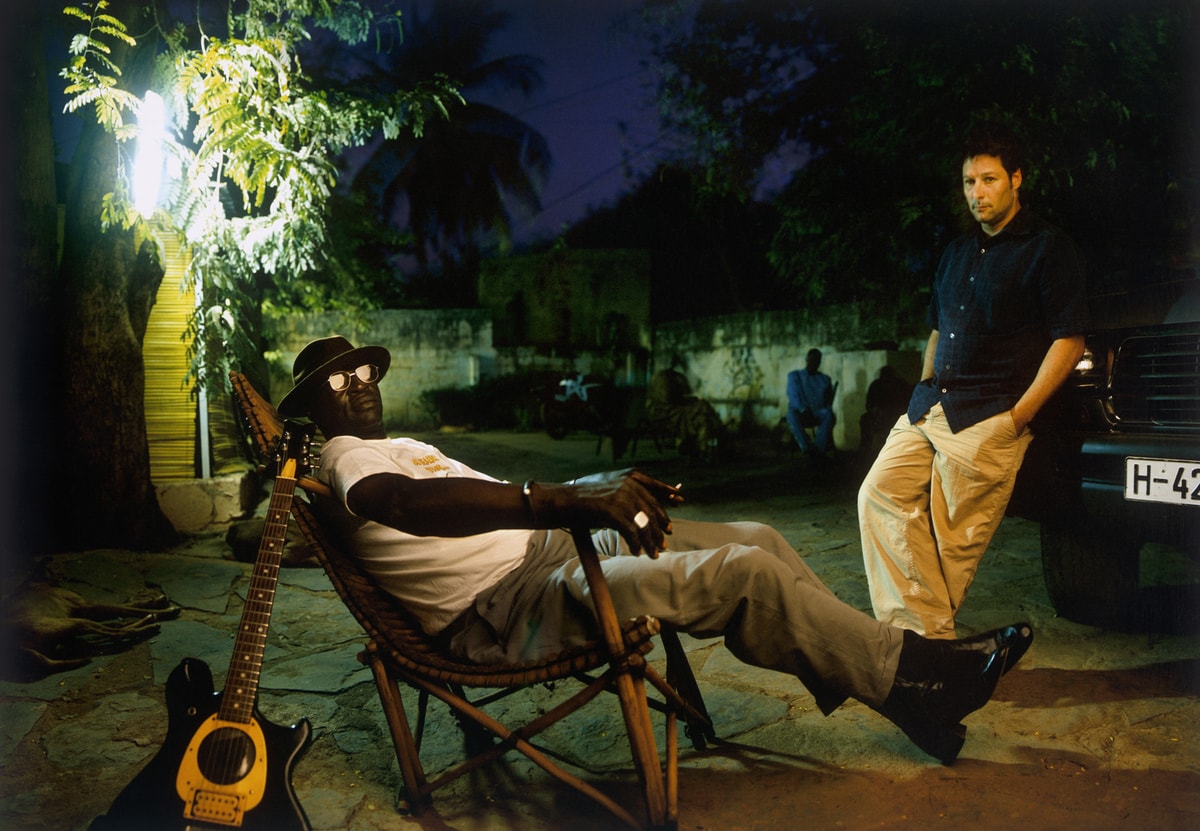

Photo: Ali Farka and Ry Cooder at studio Bogolan, Bamako © Jonas Karlsson

Paris. Sitting at the bar of an hotel located within a stone’s throw of Gare du Nord train station, Nick Gold is gazing at a wall of vinyl records and his eyes stop on the album of Franco – the Congolese musician, dashing and smart with a large smile on his face, is standing in front of Pigalle metro station. The picture was taken at a time when Paris was undoubtedly the advanced post of African music in the West. However, London also had its crew of enthusiasts, who would soon undertake wondrous projects. Nick Gold was one of them. The world owes him Buena Vista Social Club’s success and the worldwide dissemination of artists such as Cheikh Lô, Oumou Sangaré, Orchestra Baobab and Ali Farka Touré. More than thirty years have passed since the beginning of World Circuit, a label he finally sold to the BMG group, although he still runs the artistic direction. The young keen jazz listener and soon-to-be-teacher, who earned a living working in record stores, did not know that music was going to change his life to such an extent. And more particularly the sounds originating from the African continent: the first time he entered a studio, it was to record Kenya-based Shirati Jazz. Some time later, Nick Gold met a Malian artist who would eventually find a place in his own pantheon of music heroes: Ali Farka Touré.

When did you hear Ali’s music for the first time, and how did you two meet?

It was around 1986, 1987. Ali’s music was being played on the British radio at that time by two Djs, Andy Kershaw and Charlie Gillet, and this is how we got to hear about him. His albums were starting to be reviewed in magazines too. I think that Andy, one of the two radio DJs, came to Paris, and as he was buying African records, he picked up this one by chance. Ali had already released a series of records in France.

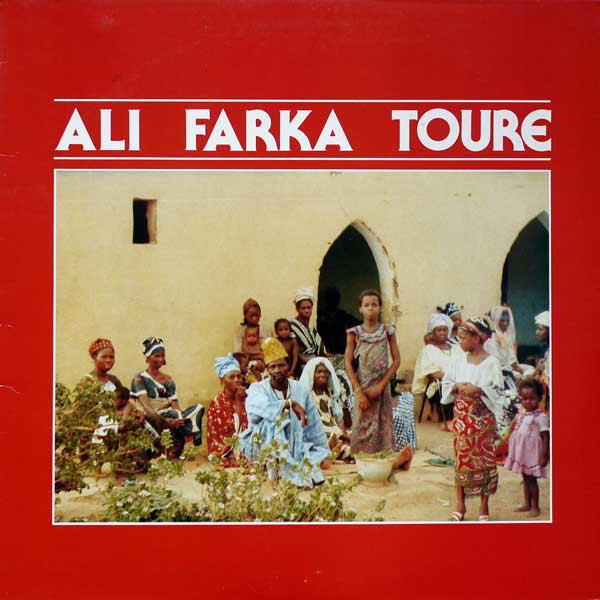

One of them, that would be known as “the Red album”, had just a photo of him and some other people on the front cover that only read “Ali Farka Touré”, with the tracklisting printed on the back. No other information at all… People loved this record because it was just acoustic guitar, voice, and percussion. It was sort of mesmerizing, you could catch glimpses of blues music, and a little quote of an Otis Redding song. This helped people identify themselves with the music, and whoever heard the album liked it immediately. It has very strong songs, the repertoire is very good and it is beautifully recorded… It’s a great record!

Although many people started to talk about it, the music still remained a mystery because of the lack of information – we didn’t even know where it was from…

Ali Farka Touré – “Red Album”

Toumani Diabaté, who was working in England with Womad [an England-based music festival founded by Peter Gabriel] at the time, assured the man was from Mali, where he was already a famous musician. This is when Anne Haunt, who I was working with, went there to find him. She went to the national radio station in Bamako, where he had used to work for many years, and she asked for him. They made a special broadcast and they just said “there’s a white woman here looking for Ali Farka Touré. If he is in Bamako, can he come to the radio station ?” Although he was living in the North of the country, in Niafunké, he happened to be in Bamako at this time, so I think it was luck. He met Anne and she brought him over in London to make a series of small concerts and record music. So the first time I met him was in the taxi, as he was just off the airplane that brought him to London.

What did you like about him?

Apart from his music which captures you very quickly and quite powerfully, he was really a “larger-than-life” character, incredibly charming and self-assured: the sort of person everyone will look at when he enters a room. Now imagine when he would start to play music in front of you!

The most beautiful thing was to watch him play the guitar because it seemed like he was at one with the instrument, literally caressing the wood in an effortless gesture. He really lived it. Every note Ali played was meant. There were no useless doodles or fills, it was very subtle and mesmerizing.

When you have been listening to records for a long time, you have a list of the heroes you think you will never meet – like Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Charlie Parker or Lester Young… You think you might be able to see them on stage – if they are not already dead. So being with Ali in a room and watching him play, you realize that he’s someone of that stature, of that level – more than anyone I had ever met before. Someone very special and important to me.

Was there any connection between his guitar playing and the way he played the traditional Malian instruments?

Yes. I think the first instrument he had was a one-string traditional guitar called “njurkel”, generally used to summon spirits during ceremonies. But musicians played it like a ngoni, with a lot of hammering-on [a playing technique performed on a stringed instrument by sharply bringing a fretting-hand finger down on the fingerboard behind a fret, causing a note to sound]. He fell in love with the instrument as a young boy. And then in 1956/57, in Guinea, he saw Kante Facelli [a famous djeli guitarist, at that time member of “Les Ballets Africains de Keita Fodeba”] play guitar: he was immediately captivated and since then he had always wanted to play guitar. At that time, earned a living as a chauffeur. I think he finally got a mandoline or a guitar, a borrowed one, and he said that he just transposed the technique of the njurkel to the guitar, a very easy task for the young amateur musician. The only problem, he said, was that as he had now six strings instead of one, he was worried about the other strings being jealous of the one he was touching. So he had to find a technique to play with the other strings too…

The Western audiences called his music “blues”, but I heard Ali wasn’t pleased with it.

It’s true. He became very frustrated after being asked about “blues” all the time. Because I think most of his music was traditional music transposed on guitar, while here in the West people could only hear echoes of the blues.

Nevertheless, I think he was aware of the existence of blues music, as he could play it and he even included in his own compositions, influences of foreign music he had listened to. you can hear it in the song “Amandrai” where he sang in Tamashek language, which is a very straight blues-sounding song. He had already heard a Tamashek version, so he brought in little bits of Western blues he had heard. He had an amazing facility: if you hear Ali’s traditional songs played on a ngoni, the melody and the obvious structure of the song isn’t so apparent, but when he played it he was able to highlight the melody so that people would hear it better. I don’t think that he was purposefully doing it to make his music “easier” to foreign listeners; I think he was just able to interpret what he thought was essential in something he had heard.

People said they heard touches of blues in Ali’s music, and I think he got frustrated and sometimes pissed by these reviews because he considered that 90% of what he was playing, and even more, were from Mali. Malian music that happened to be played on a Western guitar with little bits of stuff he had heard somewhere else… But because of these small quotations, people thought he may have borrowed more than he could compose.

Ali Farka Touré has worked for many years at Radio Mali. Do you think the experience had an impact on his ability to produce a unique synthesis of the various music styles played along the Niger river?

As an ambulance driver and as a chauffeur, Ali travelled a lot. Besides, at Radio Mali, Ali was the assistant of a sound engineer called Boubacar Traoré who was did all the recordings from the ’70s and ’80s, including the albums Ali released on Sonafric, as well as many other musicians: The Ambassadors, The Rail Band… As part of the radio activity, the pair also made various field trips where they would record local musicians around the country with portable recording equipment. They would do frequent travels into the North of the country, so Ali got to hear a huge amount of music – basically all the regional musics. Boubacar told me that Ali would be able to pick this music up very quickly.

He was Songhai but he could also sing in Bozo, Tamashek and Malinké: he picked up languages very easily too. I don’t think it’s very common for someone to be able to bring together all of these different elements. It must be noted that it was the era of the “biennales”: every two years there were regional competitions that would lead to a national final competition in Bamako. It means that all these musicians and music were coming together, at a regional level, and they all shared a strong awareness of their different cultures and music, with a true pride and a real interest in it.

This sharing of cultures was in the air. You could see that when he made the record with Toumani in 2005, In The Heart Of The Moon. I think Toumani was surprised by how much Mande music Ali knew. When they made that record, they sat down to play and Toumani said:”What are we doing first?” and Ali would just start playing a Mande song that even Toumani didn’t know so well. His musical knowledge was huge.

Nick Gold, Ali Farka Touré & Toumani Diabaté (Bamako, 2004) / photo Christina Jaspars

Working with him in a studio was also a very special experience…

He didn’t like recording very much. I don’t know if he liked the process of examining himself in this environment: playing and listening back. He would record and if you said, “Can we do that again?”, his general reaction would be:

- “Why? What’s wrong with it?

- Maybe you could do this section a bit better…

- Look, I’ll do it again if you want me to, but it won’t be better, and it won’t be worst. It might be different.”

And so he’d do it again but he didn’t like to analyze these things, he only liked to play… It made the recording process very fast. I remember the recording we made of Talking Timbuktu with Ry Cooder: it was made in two and a half days – and the days were short days – with a band that he had never met before. Ry had to work fast because even if we had worked a bit of repertoire before he entered the studio, Ali would start playing the tune, and Ry was still thinking, “which guitar should I put on that?”. Well, you had to pick up your guitar and go with it, because Ali was already off… You had to catch the train! For most of his recordings, there is very rarely “take two” or “take three”, nearly everything is the first take. “Bam! Finished, and move on.”

When it comes to the album Talking Timbuktu, how did you make the connection between Ry Cooder and Ali Farka Touré?

I got a phone call at the office one day. We had a tiny office with an intercom, and when the call came in, I heard somebody said: “there’s a call for you on line three, it’s Ry Cooder.” I said, “ok, very funny,” thinking it was a friend of mine. “Hello?” I said. Then this voice came down and it was very obviously Ry’s: “I need to find Ali Farka Touré.”

It was just a very great coincidence because Ali was staying at my apartment at that time. Ry had a concert the next day but he had free time, so I invited him over to my apartment. As we didn’t have anything to sit comfortably, I had to go buy a chair and a sofa before he arrived; I also had to cook some food so when Ry came I realized I had forgotten to get a guitar for him. There was only one guitar for the two of them, so they swapped the instrument and played a little bit. Then Ry said: “Ok let’s try to do something one day,” because he really liked Ali. This is how we started to gather bits of repertoire, and send them to Ry. Eventually, when Ali went on a North American tour, I made sure he had three days off next to where Ry worked, and I found out which studio he liked to work in, where I booked some studio time. So Ry came, and we did it quick. I think we had one day of rehearsal at Ry’s house before their recording session. And that’s all. I also booked Texas-based guitarist and violin player Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, and Ry broughtdrummer Jim Keltner. Together they just hit this music out, very quickly.

There was something fascinating with Ry: when we were recording in one of the studio’s huge rooms, he put microphones high up into the ceiling to catch the ambiance of the room. It turned out to define what the sound of the album would be. This detail was very interesting to me because at that time, the trend was close-miking everything – the engineers wanted to control everything and the real pride was your ability to record a guitar when everything else was playing, and only hear the guitar back. But for Ry, it was the complete opposite: he wanted to record the musicians’ interaction in the room. He also wanted the musicians to play really close to each others, so he and Ali were sitting very close to get some physical interaction and let the inner dynamic happen.

This very album, recorded in only three days, eventually was awarded a Grammy award in 1994 and became the label’s first international success?

Yeah… And it’s a great record.

Ali Farka & Ry Cooder with Joachim Cooder (Ry’s son), studio Ocean Way (California). Photo: Susan Titelman