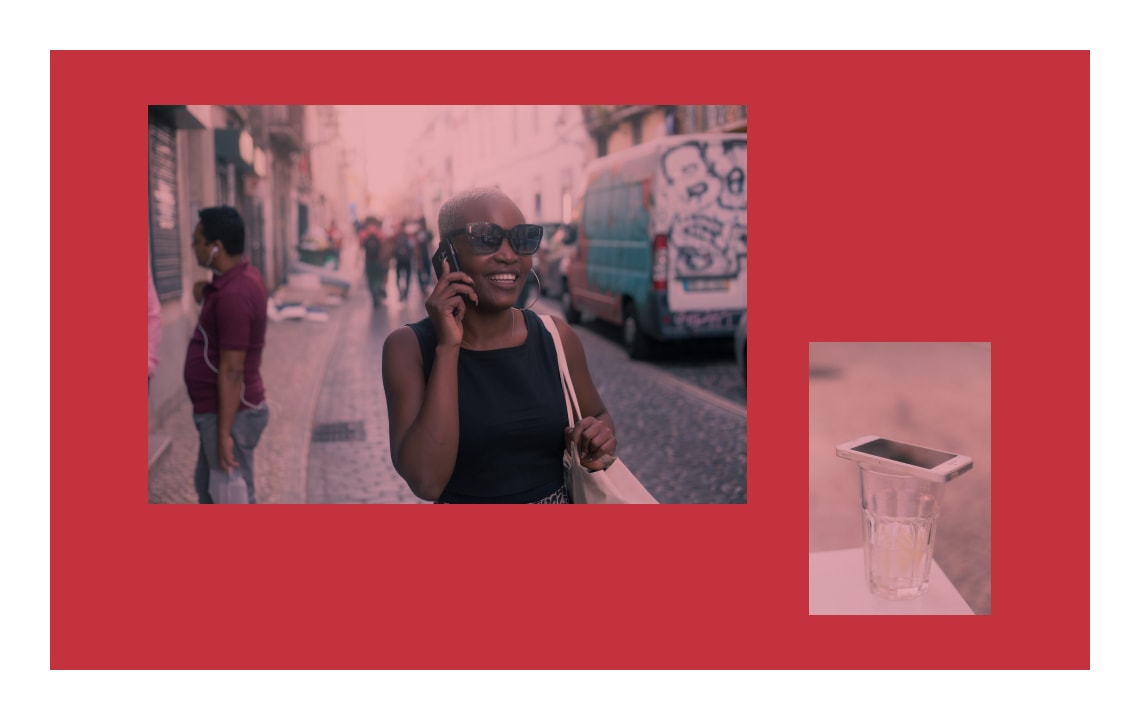

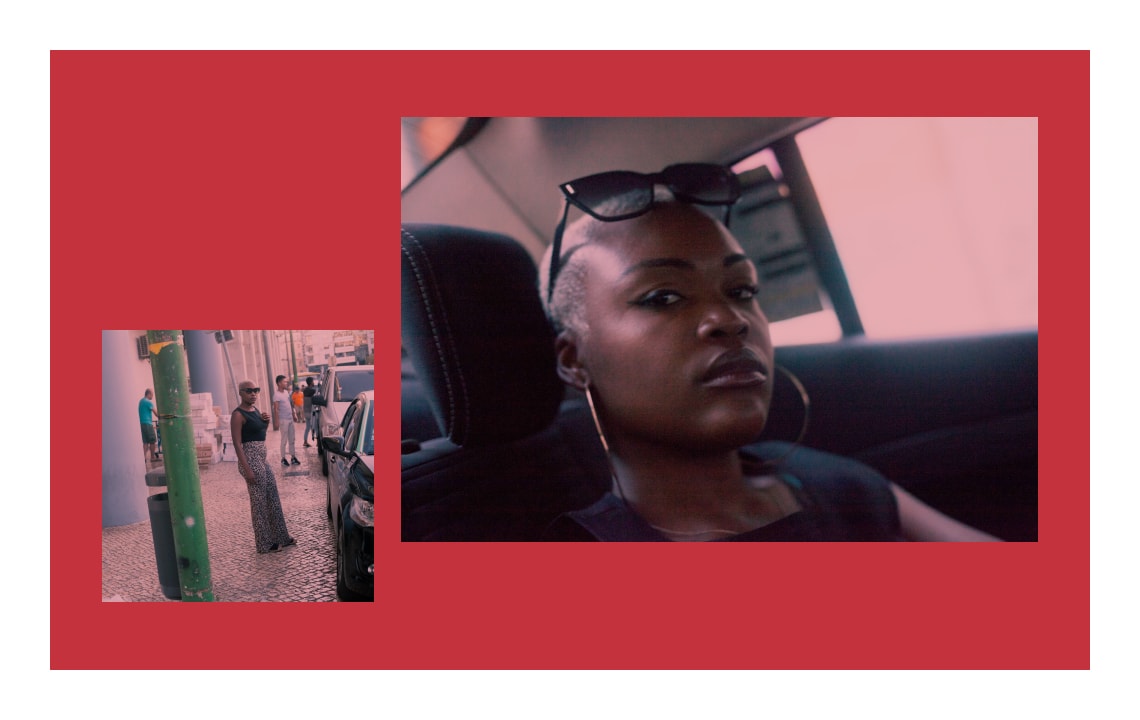

With shortly cropped bleached hair, huge gold earrings, and shiny polished nails, 25-year-old Pongo is an impressive young woman. She doesn’t go unnoticed, even in the Intendente square, in the heart of a cosmopolitan Lisbon. The city that saw her grow following her departure from her war-torn native country, Angola, and helped kick-start her career with force: featuring on Buraka Som Sistema’s single – “Wegue Wegue” – that aired on radios worldwide which engaged M.I.A. to take an interest in this new world of “electronic kuduro” music.

Photography by Nuno Barroso

Today, Pongo – real name Engrácia – has chosen not to rest on her laurels with what she created ten years ago. The same girl who brought her flow and lyrics to Lisbon suburbs, her breed of urban kuduro return with a shortened name – exit Pongo Love, a tribute to Congolese star M’Pongo Love. Five songs, in Kimbundu and Portuguese languages, musically connect the dots between kuduro, dancehall and electronic music.

A retrospective of the ten years that allowed her to mature with the fruits of an artistic rebirth, but also a more intimate one. Ten years during which Pongo Love the teenager was sent to the lion’s den and learned to fight in a hostile and sexist world to become the fearless lioness – Pongo.

Nine: The age of her arrival to Lisbon from her native Angola

“When you arrive at an early age in another culture and another country, you have a naive and innocent vision of the world. One of the things that struck me the most when I arrived at Lisbon airport, was the escalator. My brothers and sisters and I were all dressed with our baptismal day clothes, and our mother asked us to sit on the steps so she didn’t have to watch us. Obviously, we quickly found ourselves at the top of the escalator, and our clothes managed to get stuck in the escalator! My mother shouted ‘Help!’ so strong that the airport staff immediately came and stopped the machine. [Laughs] I also remember my mother, at Rossio subway station, raising her hand when the train approached, thinking it was necessary to call the driver for it to stop. [Laughs] These are very fond memories.

But quickly, while growing up, I also started noticing the negative things. We were living in Pontinha, a small city North of Lisbon, and we were among the very few Africans in the neighborhood [the majority of people of African descent born in Portugal’s former colonies have immigrated since the 1970s to neighborhoods and cities mostly West of Lisbon; Author’s note]. So you can imagine my daily life at school… I was a permanent target of mockery and bullying, purely because of my skin color, my hair, or my accent. A truly violent harassment.”

A cruelty that perhaps explains the idealization she creates from her childhood in Angola, a subject that turned out to be the main inspiration of her lyrics. “I prefer to forget these sad episodes and instead, speak about my childhood memories in Angola. The little games I played with my friends, our songs, our dances, our slang words: it’s an infinite source of anecdotes and stories waiting to be sung.”

A teenager of the African community in Lisbon’s suburbs

As a teenager, a twist of fate propelled her unexpectedly towards the path of urban music. A cheeky and reckless kid – “I was always doing stupid acrobatics” – she fell several storeys from a window and miraculously escaped with only a broken ankle. This brought her to attend regular consultations with a physiotherapist, far from her family’s home. To get there, she had to take the Sintra line train, a transport axis that serves the suburbs home to strong Afro descendent communities. Her weekly stop at Queluz station, was where she would attend the improvised music and dance performances of a group of boys who practiced kuduro on the streets, became a decisive meeting. The Denon Squad adopted her and invited her to come and dance with them, then shortly after to sing on the choruses, after they noticed her unique flow. “You’re hanging out with bad boys!”, her father reprimanded her, who nonetheless had given her the taste for music, as he too made himself a reputation as a kuduro dancer back in Angola. But there was little effect in trying to discourage young Pongo: his daughter had already placed her feet in the battle, with a broken foot nonetheless. A twist of fate that is forever etched into her skin, in the form of a long scar across her calf. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

At 15: The Buraka Som Sistema years

Forced to accept the path of his determined daughter, and unable to resist the infectious nature of the movement, her dancer-father became her manager, more capable in avoiding the low blows newcomers receive in the business, especially young female newbies. Pongo acknowledges the key role her father played in his musical education: “I drank from the same cup as my father.”

Everything then accelerated: her friends from Denon Squad sent a cassette demo of Pongo’s vocals to a collective of musicians/producers from the neighboring suburb “Buraca”. And here is when the young chorist-dancer entered Buraka Som Sistema’s studio for a test. She impresses them by debuting what would become the successful hit “Kalemba (Wegue Wegue)”, a unique collage of her childhood memories in the Cuca district of Luanda, with a hyper and ultra-precise flow.

A legendary MusicBox concert, in the heart of Lisbon, with shows in all the major festivals then following. The Portuguese capital loves Pongo and Pongo serves the city well: she quickly became a key figure in the Afro music community, until the generous Hernâni Miguel, a key figure in Lisbon’s club night scene since the 1980s, took her under his wing. The Guinean immigrant who helped revolutionize the musical circuit of a city that had just been liberated from the burdens of the dictatorship, saw in Pongo the strong liberating potential of the artist’s flow and charisma.

But Pongo, a minor born in Angola, saw her wings clipped by the Portuguese and European administrative machine, who made it difficult, even impossible for her to obtain the travel documents she needed to tour outside of Portugal. In addition to this institutional racism, was also a tension amongst the band about the role she was meant to play on stage and in the studio, and Pongo eventually decided to throw in the towel. At the same time, it’s at her family home that she is needed the most: forced between an alcoholic and physically abusive father towards his daughter and his wife; an overwhelmed mother; and brothers and sisters in need of being raised and supervised. Following a release, that went rather unnoticed in 2013, “Mangolé”, Pongo left music, founded a family, and continued to remember her happy childhood in Angola.

At 25: Pongo is free and wants to free her audience

Today, Pongo lives in Queluz, a few minutes from the physiotherapist consulting room, and by the train station that put her on the tracks to kuduro. Determined to keep transmitting her Angolan culture – slang, legends and way of life – and to show that music can be a healing therapy for souls, the young mother has taken up the pen and penned five songs in her own image: an eternal child, impulsive, fanciful, mischievous and teasing. A lioness in the making that you won’t try and put in a cage any time soon.

Follow Pongo on Facebook and Instagram.

Listen to EP Baia here.

Read next: Karol Conka, Curitiba’s free spirit