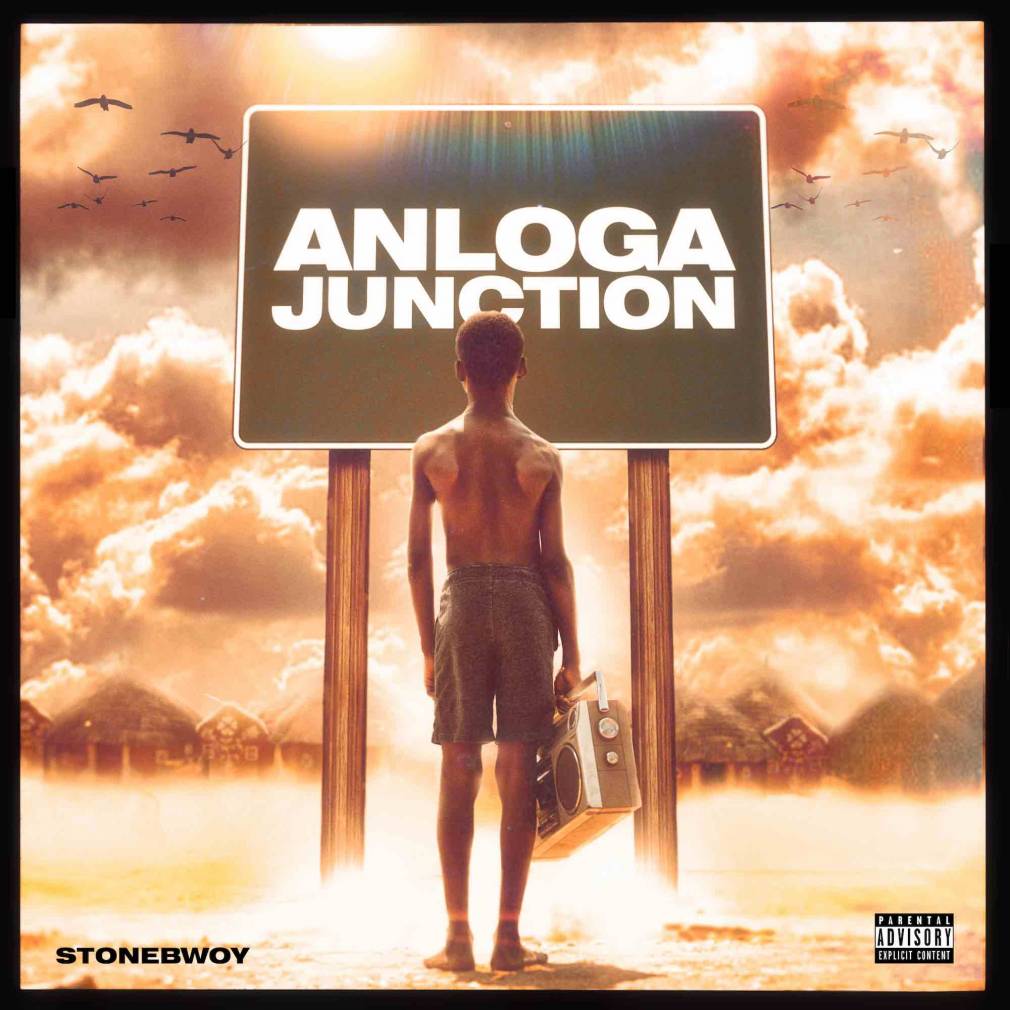

Following collaborations with the likes of Sean Paul, Sarkodie and Burna Boy, the Ghanaian singer continues his popular ascent with Anloga Junction, a star studded album riding the inspired waves of The Black Atlantic without forgetting Stonebwoy’s hometown of Anloga.

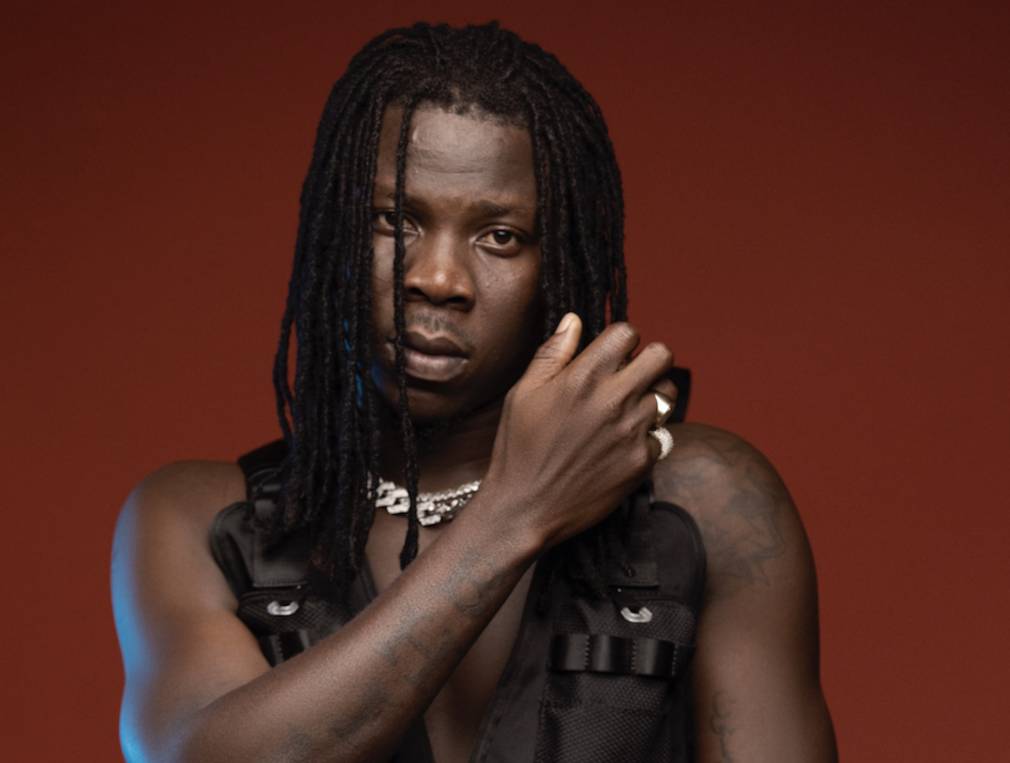

In 2019, Ghana surpassed South Africa in becoming the largest producer of gold on the African continent, whilst also going into competition with Nigeria, in establishing Ghanaian musicians on a global scale. Amongst this fountain of talent that turned Ghana into an intensive musical laboratory, a name stood out from the top of the charts for several months: Livingstone Etse Satekla, aka Stonebwoy.

Anloga

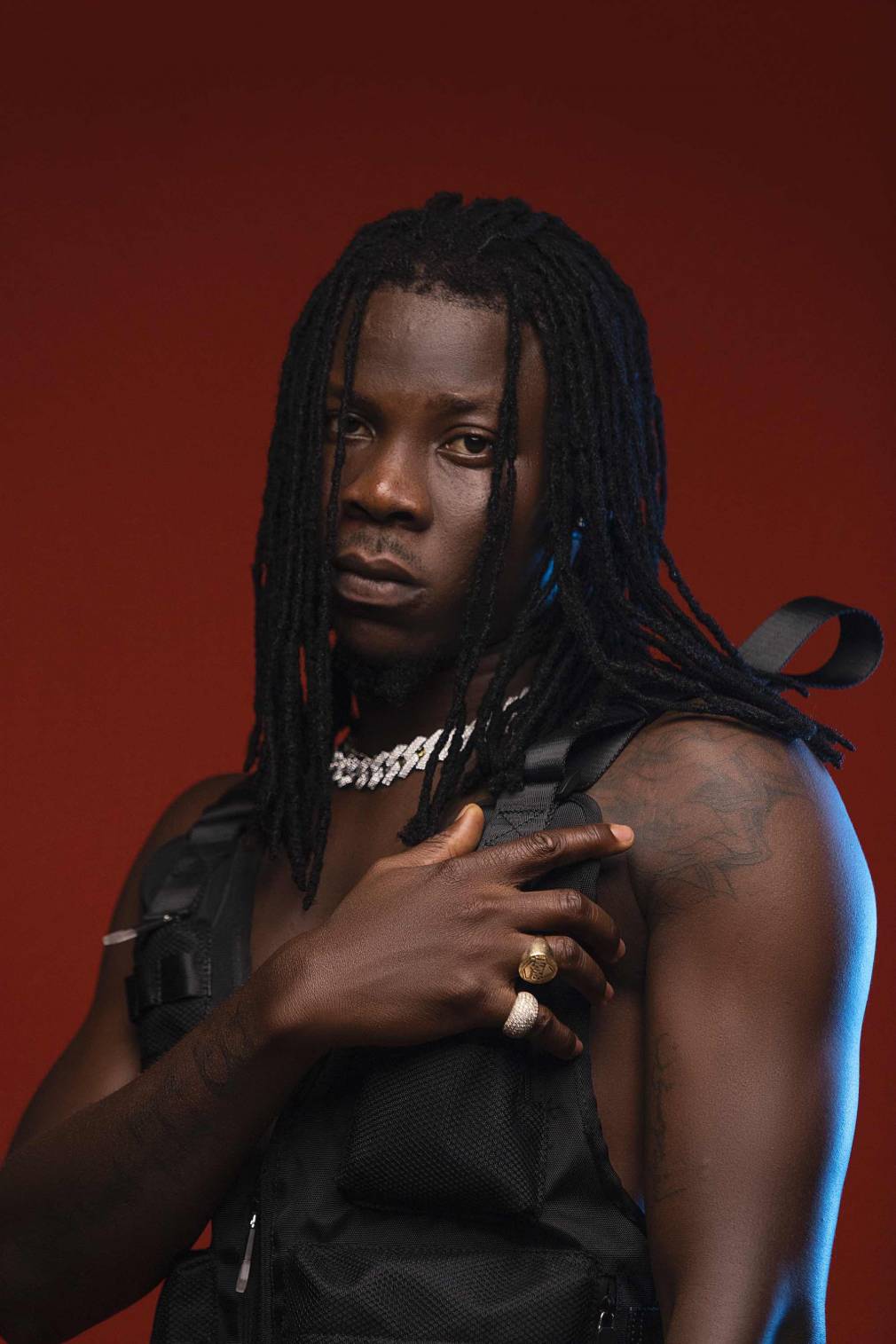

Following the raw debut productions of #Grade1 (2012) and Necessary Evil (2014), and then Epistles of Mama (2017), a more intimate double album dedicated to his mother, the singer seems to have found the perfect formula in creating his “afro-dancehall or African dancehall”, a fusion of Afrobeats and dancehall sprinkled with touches of reggae, soca, R&B and hiplife. Whilst openly claiming responsibility for the creation and success of the genre – at the risk of provoking his rivals, Shatta Wale in the first instance – Stonebwoy also recognizes that he has somewhat matured: his new opus Anloga Junction is proof, made clear as early as the opening track “Le Gba Gbe”. “I’m like a diamond being refined now. I’m at the junction of my influences, inspirations, identity and ambitions. In the last ten years, I have found a way to grow up spiritually alongside with my music, it’s a growth process. Today I’m able to celebrate my ethnicity. From being a son of the soil of Africa, in this world where people are lost, you really have to know where your roots are, to acknowledge them and to spread the diversity of our cultures.” With a clue in the title of the album, Stonebwoy’s roots are in Anloga, a fishing town made of sand in Keta Lagoon, 160 kilometers from Accra. “That’s where my parents were born, where the elders and ancestors live. It’s not far from Accra so we used to go there a lot and we always loved it. This countryside is very beautiful and wild. It’s a big inspiration for me,” he explains. Naturally, he puts his family in the spotlight for the “African Party” video. Whilst Stonebwoy has sung the majority of his hits in English, he now takes it back to Ewe, the language of the Anlo people, which holds a certain magic. More surprisingly, the record also features a few songs… in Jamaican Creole!

Bridging the gap

The son of a middle-class upbringing, Stonebwoy grew up in Ashaiman, a suburb in Accra. “I was lucky to grow up in Ashaiman. It’s a blessing, a privilege, and I’m very grateful for it. I grew up in between the low low kids from the ghetto and the upper class people. So I grew up with different cultures and a bunch of different types of musics.” Before switching to dancehall permanently – by nature more festive, lighter and perhaps even more modern – he first fell in love with reggae. That of the Jamaican founding fathers (Bob Marley, Burning Spear and Peter Tosh); that of their descendants (Damian Marley, Jah Cure and Sizzla); and that of Africans such as Lucky Dube and Rocky Dawuni, a generation that united many Ghanaian Rastafarians since the ’90s. In fact, it’s not in Ethiopia – the land of messiah Haile Selassie I’s – that the largest Rasta community on the continent lives, but in Ghana, a very tolerant country towards Jah’s worshippers, unlike many African countries where dreadlocks, vegetarianism and ganja do not mix well with the local culture. In addition, in Ghana, President Nana Akufo-Addo campaigns for the return to Mother Nature: last year he embarked on a Caribbean tour, including a visit to Jamaica, to promote what he called “The Year of Return”, responding to a growing desire from descendants of slaves to return to the origins of their ancestors. An old story in Ghana.

Stonebwoy chose the opposite route. When he landed in Kingston, Jamaica for the first time in 2016, the singer immediately felt at home and the journey confirmed his intuition: “Reggae music is the musical connexion that reveals the terrible journey that Black people, slaves, have made in between Africa and America. It really is the connexion between the lands and the people. Africa is a bigger Jamaica that’s all. We’re all brothers and sisters: reggae brings unity.” A transoceanic union Stonebwoy has pushed for since his debut and continues to evoke on Anloga Junction, specifically on the song “Journey”.

Babylon

Stonebwoy however, seems to prefer the reggae sound to Rastafarian philosophy, and enterprise of the Rasta lifestyle. Ghana encourages business: political stability, a dynamic and diversified economy and a relaxed lifestyle… At 32, Stonebwoy has long since joined the ranks of artist-entrepreneurs.

“My drive and determination are in-born,” evaluates the artist who, as early as his high school years, has done everything he can to break through. After a few homemade singles and radio freestyles that earned the singer solid notoriety in Accra’s underground scene, Stonebwoy’s career really took off when Samini, the godfather of Ghanaian dancehall, took him under his wing in 2010. Two years later, he released his first album and launched his own label, Burniton Music Group. Then things moved on quickly: a few years later, Stonebwoy opened for Lauryn Hill and Wizkid, won a number of awards including a BET Award in 2015, followed by high-profile collabs with Sean Paul, Sarkodie and Burna Boy.

As a successful businessman, Stonebwoy has developed his own clothing brand, BHIM – Bless His Imperial Majesty – and is now investing in up-and-coming artists such as Kwesi Arthur, DarkoVibes, Medikal and Kelvyn Boy. Oddly, he also jumped into the energy drinks business: Stonebwoy became the face of advertising and owner of Big Boss’s Ghanaian franchise. What about Babylon then? “A leader has responsibilities. The more you lead, the more you sacrifice,” he answers.

African Idol

Anloga Junction is a testament to Stonebwoy’s international ambition, inviting the talents of Ghanaian pop-reggae legend Kojo Antwi, South African rapper Nasty C, North American R&B diva Keri Hilson, Tanzanian bongo flava star Diamond Platnumz, London-based Jamaican singer Alicai Harley, and even Nigerian phenomenon Zlatan. A Ghanaian, Pan-African, diasporic and global XXL cast that forgets no one. Likewise on the producer side, full heavyweights feature, including Nana Rogues (Drake), Andre Harris (Usher, Chris Brown, Kanye West), Kabaka Pyramid and Phantom (Burna Boy) the latter using, as the great Timbaland and Major Lazer did, the famous “Totó La Momposina” sample on the excellent “Critical”.

Sounds like the American dream, doesn’t it? “Yes I dream big, and I’m ok with my ambitions,” admits Stonebwoy. “My main dream is a Pan-African one. This is exactly where I am on the state of mind right now. I never wanted to leave Ghana to go somewhere else. I never had an American or London dream no no. Dreaming of moving to the US or Europe is very dangerous for us Africans. We can stay here in Africa to make it better, we can bring unity and pride.” An African pride that the singer exuberates on “African Idol”, led by the smoothness of Ewe percussion. Who are his African idols? With a machine-gun-like flow, Stonebwoy off reels a list: “Kwame Nkrumah, JJ Rawlings, but also Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X and Elizabeth Nyamayaro, a Zimbabwean feminist UN officer specialized in politics. In a word, kings and queens who have fought the forces of darkness and evil, to redirect us to a good direction for us to go. I don’t wanna go political though,” he said, anticipating the next question. “Politics has often proved disappointing. I don’t like this concept of using people and dividing them for your own [interests]. There are other ways to make a better place for the people.” Instead, much like other artists in Ghana, Stonebwoy has forged his own foundation. The Livingstone Foundation positively supports disadvantaged students with access to education and has proved to be very active amongst the poorest people in society in the time of epidemics. Solidarity however is a political action, is it not?

Download/Stream Anloga Junction.