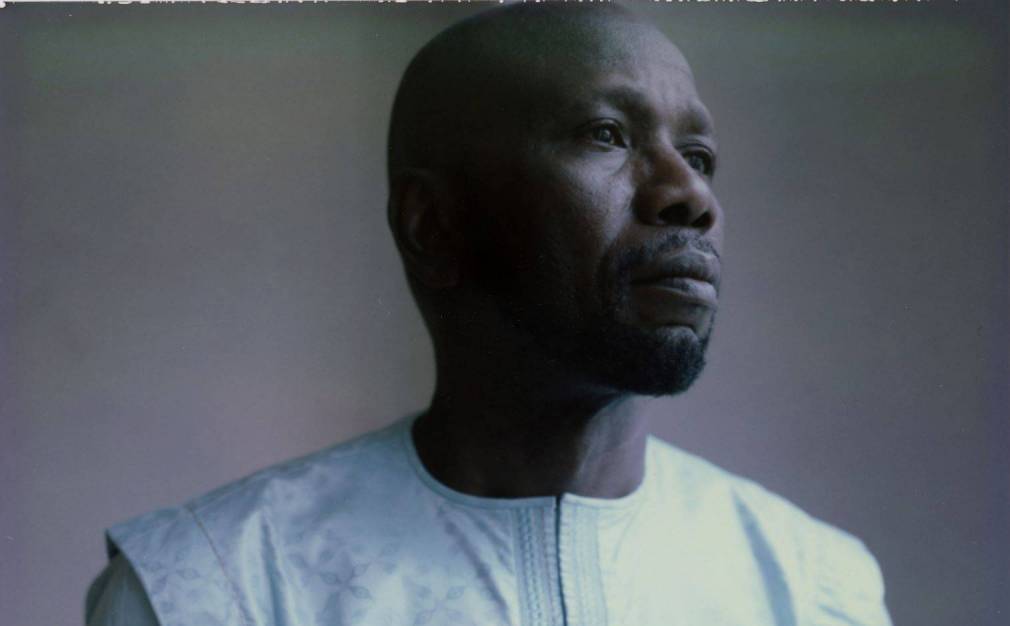

The West African jalis, also known as griots, are – as we well know – a caste of musical artists. They are the masters of the word, sentinels of universal values, preservers of oral tradition, perveyors of all types of mediation, and users metaphors and proverbs to illustrate their stories. Son of Djelimady Sissoko, Ballaké Sissoko was only thirteen in 1981 when he joined the well reknowned Ensemble Instrumental National du Mali (created in 1961) in which his late father had also played. When he took over from his father in the legendary musical group, the teenager already had a solid knowledge of the kora and a head full of wisdom.

At the age of 23, he resigned from the Ensemble Instrumental to follow his own path. Since then his solo career has been far from lonely, as Ballaké is so fond of meeting new people. He has never forgotten the Bambara proverb that says: “when birds fly in a group, you can hear the music of their wing beats.’ In other parts of the world, we’d say something like: “strength in unity.”

To gather, to unite and to highlight the uniqueness of diversity. That is Djourou’s mission, the fourth album from our Malian maestro on the label No Format. To weave this chord or rope (“djourou” in Malinké) connecting him to his fellow human beings, Ballaké has invited some unique guests, calling upon the voices of Salif Kéïta, Oxmo Puccino, Camille, Arthur Teboul and his friends from the group Feu! Chatterton. After the success of his two duet albums with collaborator Vincent Ségal, and after his time in a trio with the Moroccan Driss El Maloumi and Madagascan Rajery, Ballaké shows once again how much he excels in the art of musical conversation, bringing together artists from the most diverse of backgrounds for unique and resolutely poetic meetings, centred around the kora. Ségal of course also appears on the album with clarinettist Patrick Messina for a Euro-Mandinkan adaptation of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique. Before its release, PAM spoke to Ballaké about his career and about what Djourou means to him.

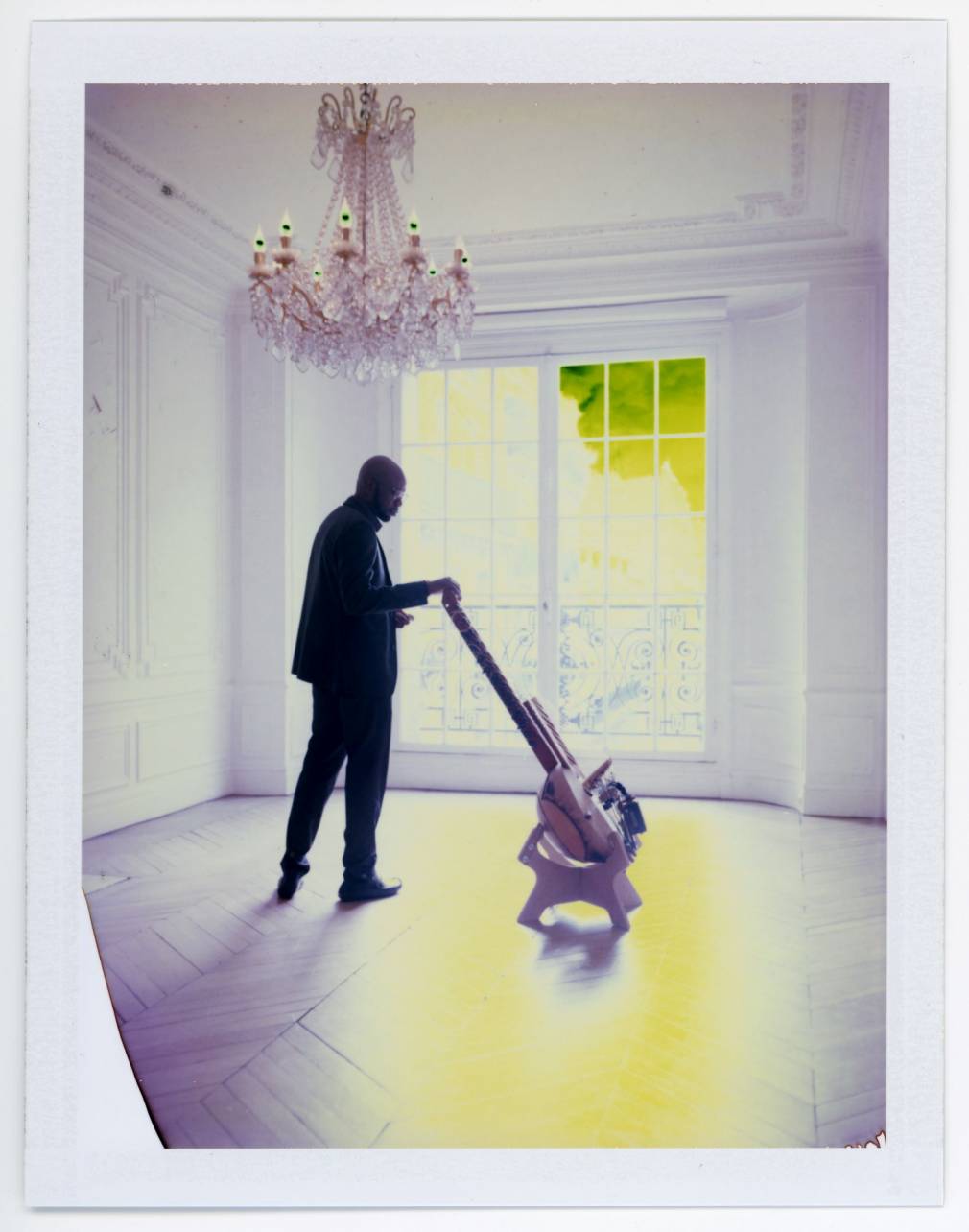

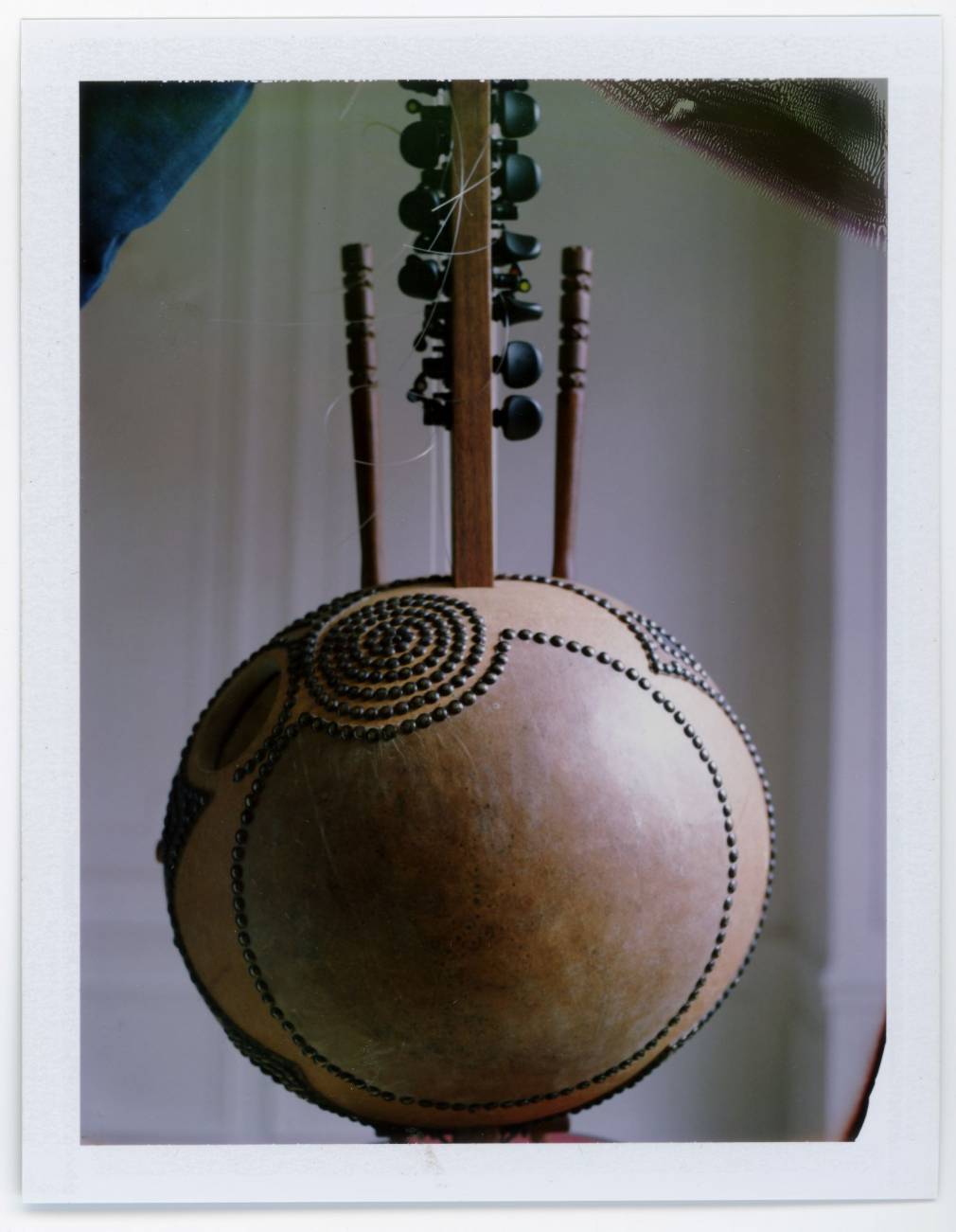

Ballaké, the musical instrument you play is known as the kora. What is its name in the Bamanan language?

In Bamanan or, let’s say, in Madinkan, it is called a korimbato. Korimbato is actually the name of the calabash in the language of the Korin people. So korimbato is the Korin calabash, that is to say, the kora. So, its authentic name is korimbato.

OK so the korimbato or kora in question is the instrument you play in your music. Where did you learn to play it?

I learned to play the kora in my family’s backyard. How did I learn it there? I used to watch my father when he played. But my father wasn’t my teacher. My teachers were my grandfather, my uncles Sidiki Diabaté (Toumani Diabaté’s father – ed.), N’Fa Diabaté and Batrou Sékou Kouyaté. I grew up with all of them. I learned to play mainly with the members of my wider family, not particularly with my father.

How come you didin’t learn from him?

First I learnt to play alone, instinctively, by watching my father, and I knew I’d never be deprived of his knowledge. You know in the Mandé we say, ‘the thing you have at home exists elsewhere’. We are strongly advised to go and soak up what we can find in other places. By acquiring outside knowledge, then adding it to what you already have, you get a richer result. So I had to go out and find other members of the family.

You like to play solo, and Djourou has two such tracks. But you’ve always liked working with other musicians, especially Vincent Ségal. Why do you like musical dialogue so much?

I like this question a lot. What is it to be farsighted? Before I went elsewhere in the world, I first played with different artists at home in my country. I gained experience with these artists. Then I thought it would be wise to observe what’s being done elsewhere, outside of my country, to immerse myself in it and see how knowledge from abroad could be combined with that of my country’s in order to move my art forward. That doesn’t mean I’m neglecting my musical roots, or that I’ll forget them. It’s not that at all. You know, having vision is about marrying different skills that can enrich any other skill. If you develop your abilities, it can only benefit you. That’s being farsighted.

Tell us about the people you brought together in this project?

You know, I don’t cultivate short-term friendships. I prefer long-term ones. One of my first friendships here in Europe was with Vincent (Ségal). And through Vincent, I met Oxmo and Patrick. Sona Jobarteh is my niece. I also met Piers Faccini through Vincent. I owe all these friendships to one person: Vincent Ségal. And all this because we admire each other. It’s sincerity that binds friendships together. And in that friendship there is understanding and collaboration. Vincent’s also forged good relationships and collaborations through me. I benefited from his connections in Europe and he benefited from mine in Africa. I’d already heard Camille’s work (Vincent knows her well, by the way) and, like Arthur, it was through Laurent Bizot (producer and head of the No Format label – ed.) that I met them.

On this new album you do a Salif Kéïta cover called “Guelen”. Why did you choose this particular song?

I discovered “Guelen” one day on one of his albums. I really liked the song. Since then I’ve often played it solo in my concerts.

One day, before making Djourou, I went to visit Salif at his studio in Bamako. There were some students doing an internship with him. I told Salif that I liked “Guelen” so much that I would like to include it in my new album. He told me that I could cover his song and backed up his support with an image in Bambara, kounadjè guiè-lé léé, ne fana guièlé-lé léé – my word is as clear as my light albino skin.

We both wanted to have a jam session right away. The guys in the studio got the microphones ready, and then Salif and I started to play “Guelen”.

Why did I cover this particular Salif song? First of all, because he’s an elder who has done me a lot of favours. He’s a star in Mali so I’m delighted to be able to pay tribute to him by covering one of his works. You know, human interdependence isn’t built in one day, it takes constant action.

Second, in Mandinkan culture, Guelen is an emblematic place where all of society’s major issues are debated. It is the place of fair and honest speech, where truths come together. It is the place where disagreements are put aside to make room for the deep, immutable values of wisdom.

We’ve noticed how much you love to improvise. What makes you favour this style of playing?

It’s just not that same here as in the West (the implication being, we don’t have written scores in Mali – ed.). I started playing with Djéli Mousso, Jali women. When you’re a beginner you start off by sort of feeling your way around. When you start to play you have no reference points. So I started by feeling my way around. The orchestra can start playing and suddenly change scale. If you don’t have a steady, attentive mind, you’ll have trouble getting your bearings and finding your place. I have practised the exercise of adapting to the constant change of scale for many years. As a result, whatever the variations in a piece, I find my way around quite easily. And I have acquired this flexibility because in my country I’ve played with various different ethnic groups: the Bobos, the Senoufos, the Mandinkas, the Peuls, the Koroboros. It is through this experience of diversity that I have learned to adapt. So, whatever the genre, I’m rarely surprised. In each new situation I manage to get my bearings.

Your new record is called Djourou (rope or chord). Why did you choose this name? What does it mean to you?

“Djourou” is a metaphor for the union of those whom I have brought together so that we can be bound by the same ties in order to achieve something that points the way for everyone; that we may be united by a beautiful spirit, to fulfil the callings of those who gave us life.

Djourou, available on all platforms via No Format.