Western travelers are fewer and fewer in Sahel today. Especially when it comes to record music. This is exactly the moment Chris Kirkley chose to explore this territory through his label Sahel Sounds, a collective adventure.

Kidal, Gao, Toumbouctou, Agadez et Illighadad are the musical territories Chris Kirkley likes to explore. There, the artists are both his alter egos and his bodyguards. When Islamic fundamentalists started to prohibit music from the desert, the US-born gentleman-explorer decided to deal and traffic sounds: Mdou Moctar’s guitars, Bamako-based Balani Shows’ unique flow, Filles d’Illighadad’s voices, and a few compressed mp3s he found in cell phones. Today he’s just back from Niger, he’s recently released Zerzura, a collective-made movie featuring an hypnotic soundtrack, and he’s meant to shoot a remake of Titanic, set in the desert…

“They’re the ones who came up with the idea: to make a desert version of Titanic, with a truck that carries migrants to Libya and broke down in the sand. Ideas always come from the artists, for the movies and for the records. It makes my job easier!” Chris Kirkley insists: the movie he wrote with Nigerian associates Rhissa Koutata and Ahmadou Madassane is the story of cultural exchanges, more than anything else, in which “every side is equal”. Together they founded a label and a studio in Niger, Imouhar Studio, because movies go with music, and vice versa. Like the reocrds he’s released onto his label Sahel Sounds, Chris Kirkley wants his movies to be tje result of a collective work, despite the distance, the digital divide, the historical differences and the exotic fantasies.

“To put the artist at the heart of the decision process has been a rare strategy in world music until now. But it happens a lot in rock music, especially in the punk philosophy”, admits Kirkley, who arrived to Sahel the way music did: by traveling on the road!

“When I was living in Kidal, everybody thought I was a North-American spy. So when I came back to Portland, two years later, the internal security department suspected me of being a terrorist! I tried to explain to them I only wanted to record sounds and music!”

He left Paris and hitchhiked via Morocco until Mauritania. There he stayed six months so he could learn this poetic French language that bears this very specific desertic accent. This newly-gained skill opened doors to the North-American traveler, just when the political situation in Sahel had started to radicalize. At first, Kirkley hadn’t plan to found a label, but just a blog. “When I was living in Kidal, everybody thought I was a North-American spy. So when I came back to Portland, two years later, the internal security department suspected me of being a terrorist! I tried to explain to them I only wanted to record sounds and music!”

Zerzura, the first “acid western” movie shot in the Sahara

From Ikea to Kidal

One must admit that a North-American going to Northern Mali in 2008 was a rare case. At that time, Kirkley was fed up “buying useless things in Ikea.” He adds: “I was bored by the American capitalist system: you’re looking for work and you end up without free time. I wanted to be free. And I know I am privileged because my family doesn’t need my help to survive.” Chris then doesn’t know anything about Mali, except a record he had been listening on repeat in the streets of New York: Alkibar by Afel Bocoum, who’s no more than Ali Farka Touré’s nephew. “I was trying to understand how he could play so many notes with just one guitar”, recalls guitarist-boss of Sahel Sounds.

When he arrived in Niafunké to explore traditional music, Kirkley isn’t aware of the way music is traded in Mali and Niger: per kilobyte or per gigabyte. By the Niger river, you can make out the first dunes of the Sahara desert. It was an immediate call for the North-American, who decided to settle in Kidal a few weeks later. “I was recording the children, the sounds of the animals, the music… but then I would just go to the bush and the weddings, only to experience the moment. And I would forget to take my recording gear out.”

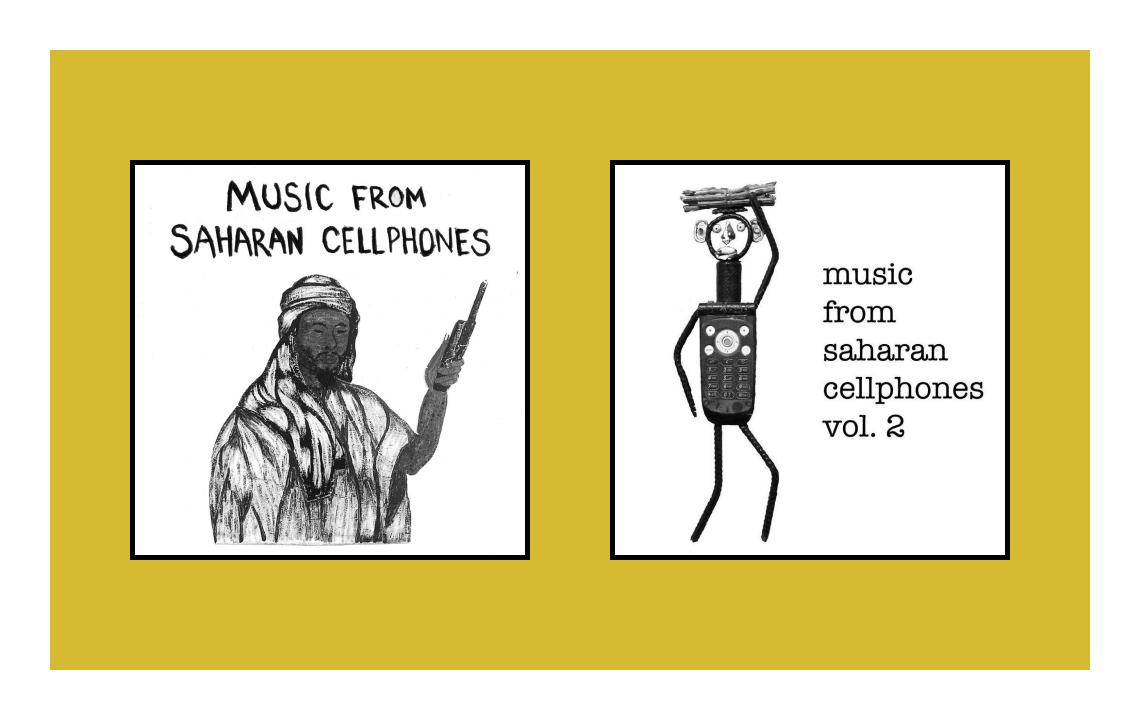

When he was recording so he could update his blog from the poorly-connected internet cafés of the Adrar region, Chris noticed that everyone was using their cellphones to record or exchange sounds. Music was being downloaded in buses or camps through bluetooth, no sooner had the tea been infused. He could have ignored the digital sounds that run through this invisible cable, and focus on his own exotic fantasies. But Chris decided to release two excellent compilations of these sounds: Music from Saharan Cellphones, Volumes 1 and 2.

The exotic sound of the desert’s cellphones

“Exotism is not necessarily a bad thing, as this is precisely what makes people like me leave abroad”, meditates Kirkley, with philosophy. “But you need to be open to novelty. In Africa you need to be ready for changing direction or idea. If you hesitate, you’re lost.”

From lost buses to hitchhiking from the markets and city streets, Kirkley started to archive everything he could duplicate, and searched for the authors. Not an easy task, though, as the tracks are not name-tagged when they’re copied to the memory cards and don’t give any additional information about the artists. And only the best of them spread into this small-scale music piracy – a network of networks that link together small portable speakers. The system offers some of the musicians enough fame to play in parties and weddings, and make a living out of it.

“This phenomenon changes music: the tracks need to be more compressed so they can fit on small memory cards, but more importantly, it opens the doors to underground music. A Gao-based penniless small rapper would be featured on the same card as Michael Jackson. It puts all the music to the same level!”

Thanks to Kirkley, you can hear everywhere the mutant music of territories where no camera is allowed to film.

When Kirkley came back home to Portland, label Mississippi Records managed to convince him to release those gems on vinyl. This is how he allowed singular musicians – such as Nigerian Mdou Moctar and Kidal-based group Amanar – to travel beyond the sand dunes and even tour in Europe or the USA. Another contribution to the ever-growing blend of nomad music, that incorporated in their mix everything they meet while traveling: rock guitars, hip-hop loops, Angolan kuduro and r’n’b… yet they never lose their own identity and history. Mdou Moctar is the perfect example of these unexpected connections. After a few odd jobs in Libya, Moctar headed to Nigeria’s studio, more than 1000 km from Niger. As the sound engineer had never heard Tuareg music, he heavily used the auto tune effect and the same production as the Indian musicals that are popular in Nigeria today! A new style was incidentally created, that was going to spread everywhere around the region. Mdou Moctar even became the star of a remake of the movie Purple Rain, filmed by Kirkley…

The Sahel Sounds compilations also feature Malian coupé-décalé and Libyan reggae. Thanks to Kirkley, you can hear the mutant music of territories where no camera is allowed to film. One of these compilations even led French dub veterans High Tones’ Dom Peter to Bamako where he met Balani Show’s MCs. Together they founded a new band, spread between France and Mali: Midnight Ravers, Sou Kono (“night birds”).

Wandering at night in unknown territories and taking risks can take you very far, far beyond the dunes, the dough, towards unidentified musical object (UMO).

Listen to the playlist of our favorite tracks from Sahel Sounds on Spotify and Deezer.

You may want to listen to: Les Filles de Illighadad’s concert at Le Guess Who Festival?

Cover photo : Chris Kirkley, Sahel Sounds’ founder, with Agadez guitarist Mdou Moctar