On the anniversary of the Brixton Riots, PAM explores the impact of reggae and sound system culture through the events that reshaped Britain’s multicultural landscape in 1981.

Header image © Sound System Culture – Nowness

“In this country in 15 or 20 years time, the black man will have the whip-hand over the white man”. Enoch Powell’s 1968 statement reverberated through post-war Britain, a comfortable assertion that the position of blacks should be one of subjugation and enslavement. The ‘Mother Country’ then was devoid of spaces where ethnic minorities were equal to, let alone owners of, whites. Voiceless and marginalised, blacks in Britain were making themselves heard in a different way. Transporting reggae, dub and sound system culture from the Caribbean, the sound of Jamaica was slowly saturating the British soundscape. The thundering bass quintessential to reggae vibrated through the streets of London in the ‘70s, a warning of the rumbling tension set to erupt in 1981 –- a year which reshaped “Great Britain” forever.

The rise of Black British culture

30 years after the docking of the SS Empire Windrush in 1940s England, a new generation of black Britons were exasperated with the racism and subjugation omnipresent in British society. Black people took their fight onto the streets, and their music came with it. Unquenched by the lack of bass in British music, early migrants had brought with them the rhythms of the Caribbean. Lord Kitchener stepped off the Windrush in 1948 singing a Calypsonian ode to London, introducing a Trini energy to the smog-soaked city that would grow to be unshakeable. Many Caribbean migrants were placed in Brixton, housed in ex-army barracks. What was then a dilapidated and ravaged part of the city, would soon come to be known as the epicentre of black British culture –- the melting pot of a new era of diversity and difference.

In the early years black music was a private affair, experienced only in homes or dance halls, – shubeens – however by the 1970s, a new generation were dismantling the barricades that separated the British streets from black culture. Unwilling to tolerate a second-class citizenship in their nation state and armed with the tools their parents lacked, the second generation was unafraid and uncompromising, much like the music that defined their struggle, the soundtrack of which was to be heard on the streets’ sound systems.

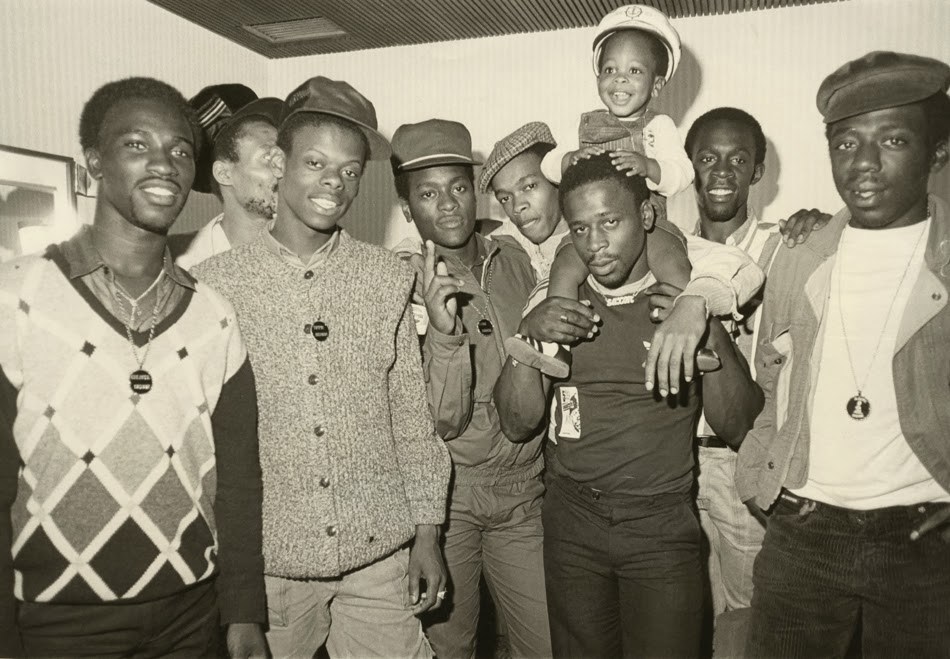

The Saxon sound system crew, 1983. (Photo courtesy of the Maxi Priest collection)

The birth of sound system culture

Sound system culture came into popularity in 1950s Jamaica, with large home-made systems travelling around the country, showcasing and battling – clashing – the best in new reggae music. By the 1970s, homegrown UK sound systems like Saxon Sound, Coxsone and Jah Shaka were declaring an independent cultural identity for black britons. The sound was protest music; bass-heavy and rebellious. As well as Jamaican imports, the systems clashed the newest in British reggae, which, possessing its own unique voice, was spearheaded by reggae all-stars Steel Pulse, Matumbi and Aswad, whose aptly titled album Babylon was at the top of the UK reggae charts on the weekend of the riots. Reggae has always been protest music, a voice for the oppressed and marginalised, yet as the 1970s progressed and racial tensions in the UK heightened, the sounds grew deeper and more politicised. Reggae artists dug to their roots. Responding to the injustices around them, the bassline was the ultimate weapon against a growing world of hatred.

Broadcasting the brutality – the New Cross Fire

As well as an expression of identity, for people of the African diaspora, music has signified survival. An integral part of the black struggle, from crossing the Middle Passage to southern slave plantations, music creates vital space for resistance and remembrance. No deeper the resonance of this than on the night of 19 January 1981 at the sixteenth birthday party of Yvonne Ruddock, when 13 black children were killed in a house fire in New Cross, South-East London. A defining moment in the black consciousness, many, including witnesses from the night, believe the fire was started as the result of a racist arson attack. The case, to this day remains unsolved, and is considered a prime example of the disregard for young black lives in Britain. Enraged by the response of the media, the police and the monarchy, the New Cross Fire saw the biggest mobilisation of black people in the UK, as 15,000 marched to Parliament to protest the injustice.

Despite the deafening silence of the British state, black British musicians broadcast the grief of the people on full blast. Roy Rankin & Raymond Naptali’s “New Cross Fire”, assertive with its emblematic dub-echo rejects the narrative imposed by an unresponsive state, declaring “Di New Cross Fire dat a murdah”. A sonic zeitgeist of the black British situation, the B-side then responds to the Brixton Riots in “Brixton Incident”. Similarly, Linton Kwesi Johnson’s “New Crass Massakah” begins with the sounds of the moment; the familiar and comforting bass that would be common at any house party of the time. The joviality is quickly interceded by “di screamin ¦ an di cryin ¦ an di dyin in di fyah”.

Equally sad and sinister is Sir Collins & His Mind Sweepers’ tributary album New Cross Fire. Reciting the alphabet with the innocence and energy of youth, Sir Collins’ son Steve opens the album and can be heard throughout. Recorded before his death, Steve Collins was one of the victims of the fire that night, and died whilst playing his sound system at the party – a gutting portrait of the inextricable link between music and the black struggle. In his poem, Johnson recounts that ‘di whole a black Britn tun a fiery red’ and rightly, the New Cross Fire was a turning point for multicultural Britain, and the first spark in the inferno that was to be 1981.

‘Event af di year’, 2 nights of revolution

With the weight of a history of oppression upon them, the black community was set to erupt. The introduction of Sus laws – the right for police to stop and search anyone they deemed suspicious – meant an overwhelmingly disproportionate number of black youths were being arrested on the streets of England. On the night of 11 April 1981, the arrest of one youth led to a weekend of revolts in Britain, the riots spreading from Brixton to Toxteth, Moss Side and Chapeltown.

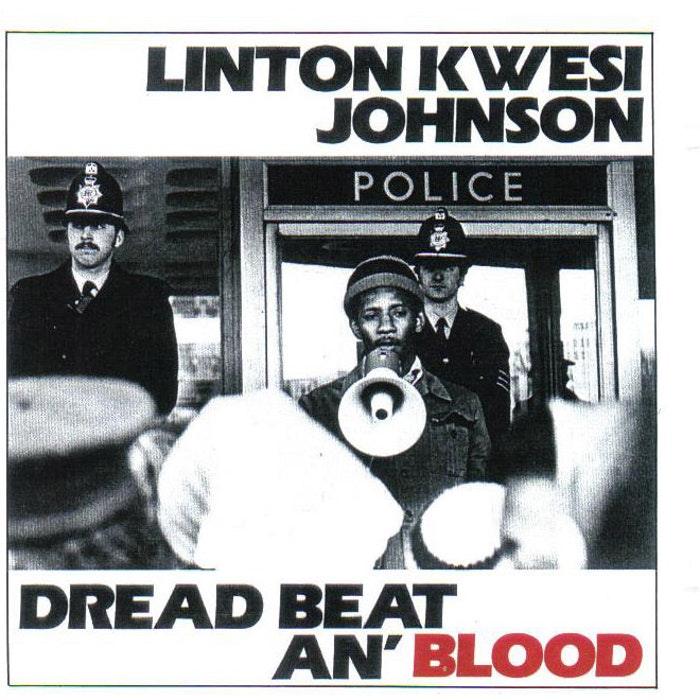

Linton Kwesi Johnson (c) Virgin Records

Few cultural artefacts document the riots better than Linton Kwesi Johnson’s “Di Great Insohreckshan”. Fusing Jamaican sounds and London life, a young black Brit born in Clarendon, Jamaica was the architect of a new style on British soils. Honouring the ancestral tradition of documenting and relaying a moment through song, the ‘father of dub poetry’, Linton Kwesi Johnson’s lyricism was a snapshot from the frontline. Accompanied by British reggae pioneer, Matumbi’s Dennis Bovell, Johnson reversed the rhetoric that was permeating British society on a black people’s resistance. Declaring this an insurrection and not a riot, the poet reaffirmed the events of 1981 as a fight against oppression, not a quest for violence.

Reiterating the agenda of black people, Johnson’s poem is a celebration of the destruction of institutions that enforce oppression and symbols of the state that were inherently racist: ‘wen wi mash up di police van ¦ wen wi mash up di wicked wan plan ¦ wen we mash up di Swamp 81’. Refuting the media’s archetype that the black man is violent and aggressive, Johnson’s poem is a reminder that the riots were not about attacking people; ‘Dem seh we bun doun di George […] we nevah bun di landlaad’. The George Inn on Railton Road, Brixton – also known as the frontline, was a pub notorious for the gathering of far-right and fascist groups. On “Brixton Incident”, Rankin and Naptali further advocate the dismantling of fascist strongholds in Brixton, referring to the ‘wicked tabernacle’, in the hope of gaining equality. The power of the reggae artists’ sonic weaponry soundtracked the people’s mobilisation. In destroying racist institutions, space was made for peace and equality, new monuments of which could be found in song. Unsurprisingly, the only song about the riots to have mainstream success was Eddy Grant’s “Electric Avenue”. Despite the upbeat R&B tempo, more palatable to a white audience than a militant roots reggae, Grant’s elusive lyrics concealed a critique of the response to the riots. Ranking high in the charts, Grant’s ode to Brixton was nominated for a Grammy for Best R&B Song to a number one spot by Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean”.

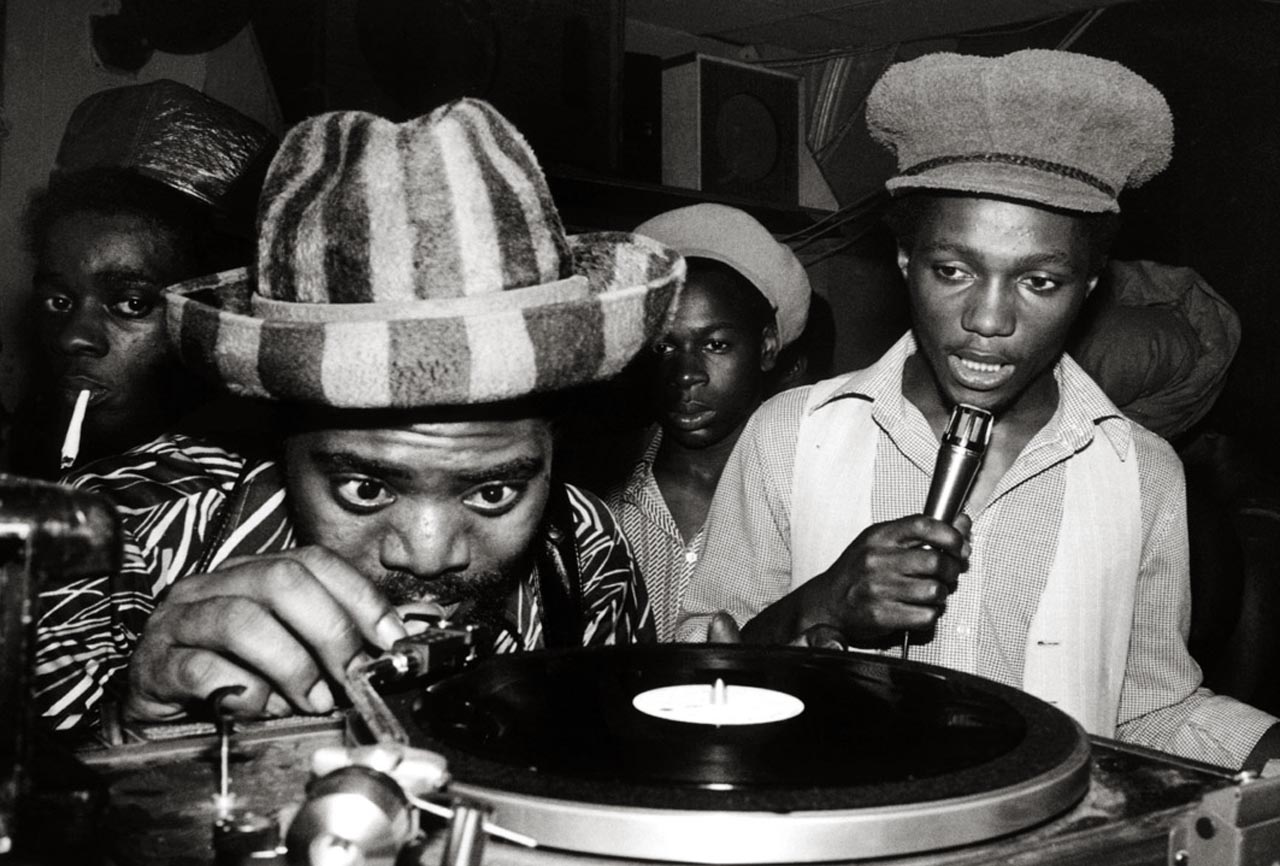

Coxsone International Sound System – Clement Dodd with the microphone

Unabashed and uncompromising, the music of the moment soundtracked an era. Not failing to make their voices heard, the Brixton Riots caused one of the biggest race-related public inquiries in the UK to date – the Scarman report, a government commissioned inquiry, attempted to address race relations in Britain, yet wholly misunderstood the communities racism affected. Despite the grief and injustices, however 1981 was a period of landmark change for ethnic minorities in England. Their cultural capital disseminated from music, claiming space and influencing spheres in politics, journalism and the arts.

As the 1980s progressed, over-politicised music fell out of fashion with a disenfranchised public who looked to pop to escape reality. However, within the communities that needed it the most, sound system culture boomed, a constant reminder to spread love and resist oppression from a fascist state, whether overtly or not. Smiley Culture, an original MC on the Saxon Sound system, released “Police Officer” in 1983. In traditional Smiley style, Culture’s ‘fast-chat’ dictated an interaction between himself and a police officer. Critiquing the state in his natural tongue-in-cheek matter, Smiley’s song remains an anthem for an over-surveilled youth. Ironically, Smiley died of a stab wound to the heart during an altercation with police in his home in 2011.

Reggae’s impact reinvented Britain in 1981 and has since spread globally. 30 years on from the riots, and with the reintroduction of sus laws in the UK, a new breed of black Brits are speaking out against modern injustices following the path carved by the second-generation. Existing to spread peace and bring joy, the message of sound systems still rings loudly against a narrative of a violent and criminal black youth. More importantly it is a symbol of the ongoing black struggle, concretising the fight in history. These defining sounds gave a voice to a marginalised society, a voice which allowed black Britons to proudly say, I am as British as you.

Listen to our Reggae, riots and resistance playlist on YouTube.