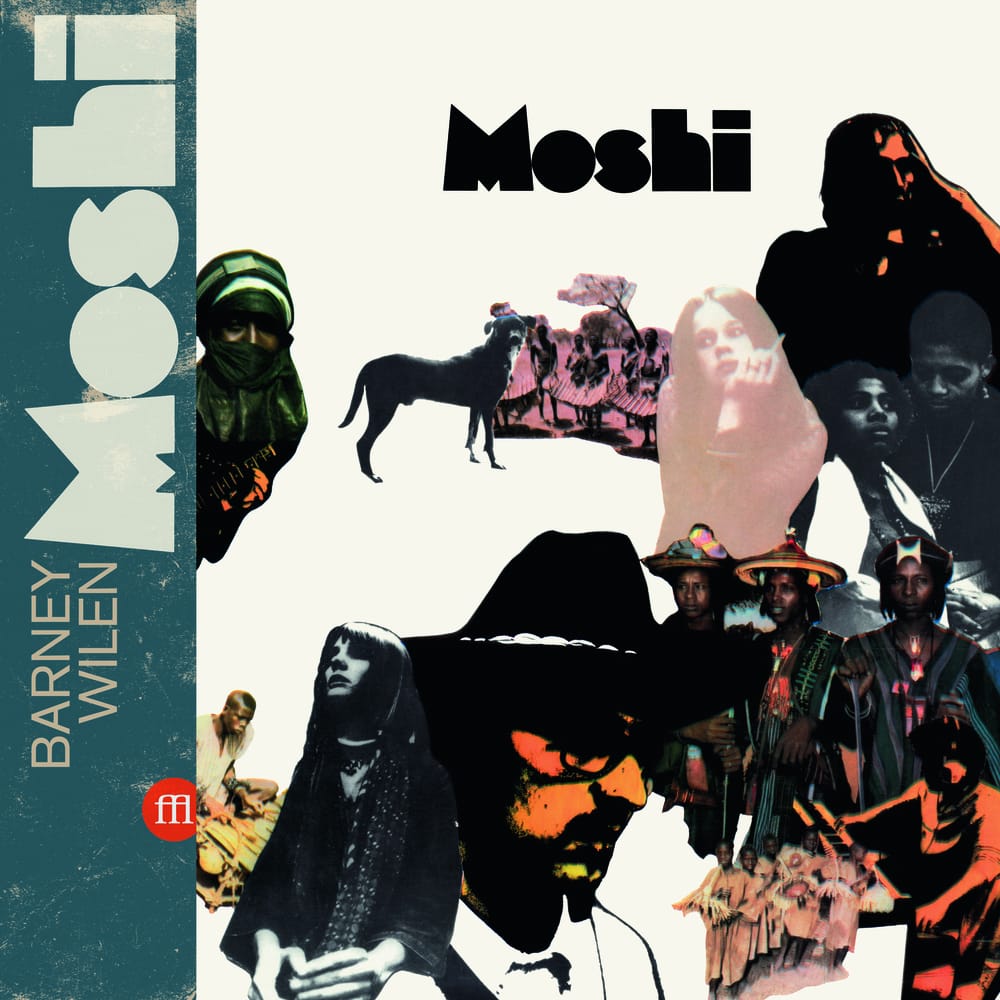

Episode 2. While everyone else was at Woodstock, the French saxophonist fled to Africa for a road trip that would give birth to the cult record, Moshi. The spirits of West Africa, funk, and free jazz come together in the same trance.

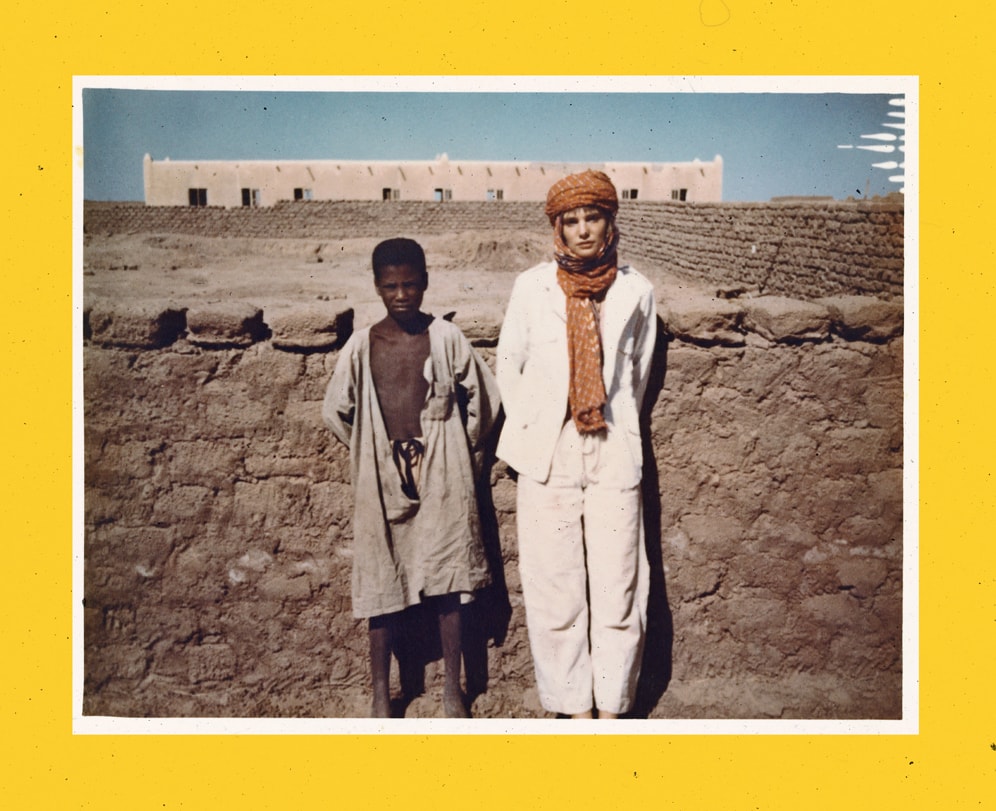

The story of this record begins in 1969. The saxophonist Barney Wilen, a prodigy of the smoky clubs of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris, and future hero of the comic La Note Bleue by Loustal and Paringaux, was in the middle of an aesthetic revolution. Two years earlier he had celebrated his 30th by recording Auto-Jazz: Tragic Destiny Of Lorenzo Bandini, recorded at the Monaco Grand Prix. Auto-jazz without a hint of auto-tune. It’s one of the milestones that those who love free jazz hope to attain. This record was followed by Dear Professor Leary a benchmark in the slanting, free jazz rock trend, somewhere between the Beatles and Ornette Coleman. A year later he decided to go to Africa, having listened to the music of Pygmy tribes. ‘We had crazy visions of jungles, deserts and bushes, lions, snakes and crocodiles, beautiful black people swinging’ and singin’. We took a map and, after a little thought, we decided to cross the continent from Tangier to Zanzibar, slithering like a snake’, wrote actress Caroline de Berdem, his then-girlfriend, in her dairy.

The objective: make a movie and record its soundtrack. They recruited a rag-tag band, and set off in a trio of Land-Rovers. On board was a 35mm camera, a cargo of musical instruments for recording, and loads of medicine they planned to distribute along the way. This was the beginning of a sound journey that was to last almost three years.

Paris to Dakar, the free jazz version

When we talk about this recording, we mean recording in the sense of something that contains a record of history. ‘When we left there were fifteen of us, but most dropped out after about six months. Those who stayed had just enough to make and record music. After two years, only three of us arrived in Dakar.’ In the end Caroline de Berdem, Barney Wilen, and lute player Didier Léon were the only ones who saw the journey from beginning to end. They returned to France laden with a pile of recorded tapes, just as many instruments, and Elvis Mammadou, a dog they had adopted whilst walking.

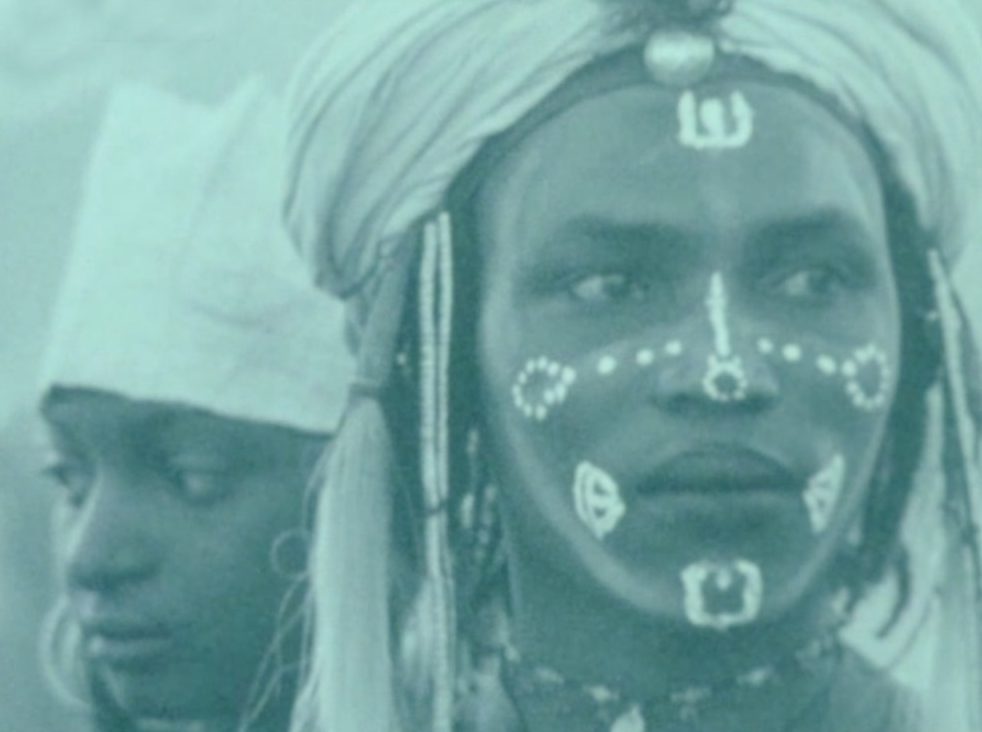

During the journey some turned back, whilst others – according to the legends – became holy men. Along the way the travellers encountered many characters, including Salah, a balafon player they met in the Hoggar mountains who accompanied the group to the shores of the Niger river, where he met an accidental death. This was not the only African who would be part of this often mystical journey. In Agadez – where they stayed for several months – they became acquainted with many passers by: Tuareg, Hausa, Beri-Beri, Mauritanians, Djerma, Arabs, and Peul-Bororos. ‘We met a lot of beautiful people in Africa, who had the beauty of heart and soul – the height of beauty for us’, described Caroline de Berdem, in rather flowery tones. ‘The house was always full.’ At night we can imagine the group singing and dancing with their new friends, the ones who would inspire them with the name Moshi. ‘It’s the way they get rid of the blues, a state of trance that includes the possession of a demon called Moshi.’

They went on to Mali at the start of the rainy season, and this was also the beginning of a string of bad luck they attributed to an ‘evil genius’. In Bamako they were denied any opportunity to record the sound of the locals, very unfortunate given the rich musicality of that city. Always tenacious however, in Niger they managed to record the sound of a griot, in the Upper Volta they recorded Balandji music, and then in Dakar they encountered the flutist Pacheco, a nickname that reminds us of the strength of Latin influences existing there. But it was here in the Senegalese capital that the journey came to an end. They would never reach their intended destination of Zanzibar. A month later it was time to pack up and head home. That, however, is the start of another story, and by no means the end of their adventures.

The art of running away together

This is a record that ‘challenges categorisation’ according to Pierre Barouh, the producer who brought the piece to life. It has a style that defies labels, that comes from deep within and hovers high above you. ‘Categories are good for radio programmers because they’re convenient. We must resist the categorisation of music, and of putting all music on punch cards into computers. That just opens the doors to a new way of splitting everything up.’ Barney Wilen’s reflections, which perhaps relate to Moshi, perfectly illustrate the issues that gave birth to this album.

Once the adventurers returned, Wilen managed to convince the label Saravah to edit the sounds that had been amassed over two years. And what a variety of sounds to contend with, if we refer to the list of the musicians thanked: the gaïta players from Jajouka in Morocco; Ali the Algerian oud player; the Touareg who looked a lot like Jimi Hendrix; Mimi the Balanji player from Mopti; Mammadou the storyteller of Bamako; Prosper the drummer from Bobo-Dioulasso…we don’t know if they all appear in these 80 minutes (reissued in full by the label Le Souffle Continu in 2017 whereas previous CD releases had hacked off several minutes), but we can certainly hear Elvis Mammadou the bush dog, in the song “Gardenia Devil”. This is, in fact, a poem about ‘Chinese people’ (it was very definitely another time…), written by Caroline de Berdem, who found herself caught in the middle of the group. The album we have today is the result of a meticulous editing process reminiscent of Teo Macero and Miles (with whom Barney Wilen had worked on Ascenseur pour l’échafaud) chiselling out electrifying grooves that just go on and on.

From there the voices were added, sometimes in chorus, sometimes alone, sometimes using spoken word or chanting, and all accompanied by the imperial Michel Graillier on electric piano. The latter was part of the team that came together to create the final album from its rough recordings, along with Pierre Chaze on the electric guitar, the bassists Simon Boissezon and Christian Tritsh, and Belgian Micheline Pelzer on drums. All at the service of a soundtrack on tour. More than just a kind of proto-world music, this record reconcilies spiritual avant-garde jazz, sliding funk, and psychedelic post-rock, amongst other things…

Moshi, with no-holds-barred

This record is something of an alien in the musical milieu. The fact that we can not only hear the instruments being played, but also a lot of the background sounds and voices that formed the ambient noise at the time of recording, lends the album the feeling of a great collection of ethnomusicology that’s been recorded in a square surrounded by busy cafes and bars. And then all of a sudden it goes crazy, an incredible maelstrom of moments, some seemingly grounded and others about to capsize, though all, in retrospect, improvised. It is hard to know where all of this unbridled creativity came from, but one thing is certain – even the most seemingly insignificant melodies gets transformed into an ecstatic trance. However, the theory behind this alchemy of sound and meaning isn’t really the important thing here; much better to just drink it all in. “Afrika Freak Out” is reminiscent of the attentive rhythms on “The Creator Has The Master Plan”. “Zombizar” only takes about seven minutes to reach the heights of spiritual jazz funk, and other titles remind the listener that if you throw together pop music with free jazz, you’re flying… no doubt this all went way beyond what Barney Wilen had first imagined.

This record, a voyage too far ahead of its time, was misunderstood upon its release. In time, Moshi would become an object of worship, the Holy Grail for listeners and musicians alike. Many jazz musicians turn to Africa looking to free themselves, only to find themselves stuck in the rut of classicism where, in the end, everything is still really controlled. Here we find the reverse – with no-holds-barred, and a desire to go beyond codes of conduct, the musicians of Moshi invented a strange afro-jazz that perfectly transcribed the atmosphere, the tears, and the joys they had experienced while travelling, constantly transforming them. An experience that is unique in every respect, impossible to recreate, and yet one that has inspired and dared others to go beyond what is expected. That’s where the great sound adventure begins…

Read next: Crazy African Jazzmen: Hank Jones meets Cheick Tidiane Seck