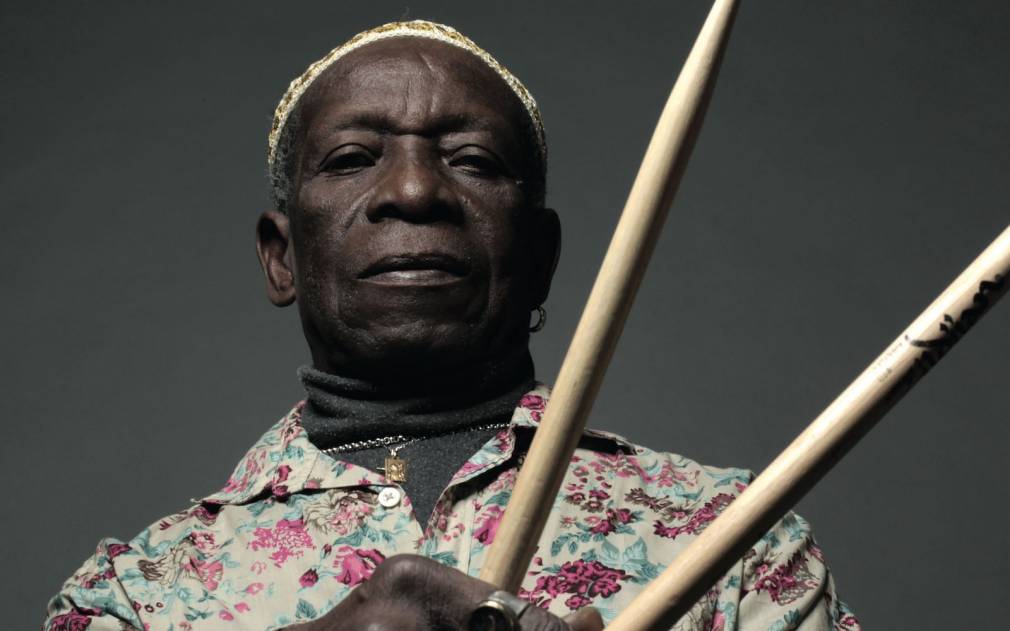

The Nigerian drummer and Fela’s travelling soulmate with whom he invented Afrobeat, passed away on April, 30th in Paris. PAM revisits the journey of the drumming genius, and his immediately recognizable sound signature which forged itself into the history of music.

“What an old man sees sitting down, a young man cannot see standing up,” says the African proverb. Sitting behind his drum kit, Tony Allen could see from afar. He now lies, rested among the other greats, following his sudden departure in Paris on April 30th. Together with Manu Dibango, he was one of the ever creative leaders, with a sixty-year career that is imperative to the history of music.

Few drummers can boast playing the lead role, like Tony Allen does. His sound was incomparable amongst the others. He repeatedly stated, “I don’t play like anybody else, and nobody plays like me”. An unpretentious claim, spoken as truth. This is why this musician who, along with Fela invented Afrobeat’s magic formula, was invited to work on so many more unique projects, where you are able to identify his unique rhythmic signature as early as the first few bars. The Afrika ’70 linchpin could have potentially taken respite following his success, but continued to pave a legacy due to his insatiable cravings to play and create, alongside diverse ranges of musicians in an equally diverse number of genres. He recently told PAM “I’m not sure I know how to stay young,”, “but I know I’m alive here and I’m doing the best I can. I don’t like to eat the same thing everyday or dress the same, otherwise I get bored easily, and the same goes for music.” Sixty years on from his debut in Lagos, Tony still hadn’t lost the lust for life and music.

From jazz to afrobeat

It was in the heart of the Nigerian megalopolis, where he was born in July 1940 that he began his professional life as a sound technician for a company from Germany. Passionate about jazz, he became fascinated by the drumming of the great Art Blakey and Max Roach. After work, he would spend his nights in clubs, soon becoming friends with musicians who allowed him to sit at their drum kits. As a self-taught drummer, he quickly made an impression and joined Dr. Victor Olaiya’s Cool Cats, one of the luminaries in Nigerian highlife. Fela had also contributed to the band, and it was at Olaiya’s club that he launched his Fela Ransome-Kuti Quintet. But it was on national radio, where Fela was hosting a music program, that he and Tony would properly hit it off. In 1965, when Fela formed the Koola Lobitos (using the name of the band he started in London during his studies), he asked Tony Allen to join him. The following fifteen years they spent together were paramount in developing their unique Afrobeat formula. They regularly performed at Club Kakadu, but their “highlife jazz” sound did not really engage much interest in Nigeria. Undefeated, they tried their luck in Ghana, where they did several tours, before flying over to the US for a trip that would change the course of their lives, and their music.

In the land of Uncle Sam, they collided with the worlds of showbiz that didn’t care much for these African musicians who came to play jazz, but also with the authorities, since their visas did not allow them to work. Stranded in Los Angeles, the band members – Tony included – started working at a factory so they could earn their living – survive – and save up to hire a lawyer. And with Fela becoming more politicized whilst in contact with activist Sandra Smith, who introduced him to the Black Panthers’ afrocentric values (1969 was also the year of the great riots in the African-American ghettos), Tony took advantage of the situation by staying put in the birthplace of jazz to master his drumming. The booming funk market also influenced the band who went on to record a few inspired tracks on the spot (later reissued under the title of The ’69 Los Angeles Sessions). If the North American odyssey was not successful already enough, they then returned to their home country being hailed as musical veterans, their suitcases packed with all the elements of this cocktail Fela had already found the name for before this trip, but not quite yet the sound for: “Afrobeat”.

Tony’s drums, mixed with percussion and bells borrowed from the musical universe of Yoruba, are the foundations of Afrobeat. Tony – the only member of the band to have had this privilege – would record two albums under his name with Africa ’70, as well as Fela of course. And it’s in this decade – with Tony on the drums – that the great future classics of the future “Black President” were recorded: “Roforofo Fight”, “Shakara”, “Zombie”, “Unknown Soldier”, “Lady”, “Water No Get Enemy”, “Yellow Fever”… The joint venture of the two men came to an end in 1978 after a concert in Berlin, Tony decided to fly solo. Times were changing. Fela renamed his revamped orchestra Egypt ’80 and Tony, after a final collaboration with Fela on Roy Ayers’ Africa, Center of the World, decided in 1984 to fly upwards onto new horizons.

The multidimensional drummer

After two years in London, he decided to settle in Paris in 1986, a city which would remain his home for the rest of his life. He recorded an album under his name in 1989, Afrobeat Express (Cobalt), however he would more often play the sideman for a number of years on a multitude of records, including Manu Dibango’s Wakafrika (1994). The Comet Records label put him back under the spotlight by teaming him up with Doctor L for the superb Black Voices, thus initiating a new phase in the drummer’s career, who would now come to take the center stage for a number of wide-ranging projects, embracing all types of genres and generations of musicians. He met with Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz) and invited him to perform on Homecooking (2002). The British musician later employed him for a number of his own projects, including The Good, the Bad & the Queen, a supergroup composed of, in addition to Albarn and Tony Allen, The Clash’s former bassist Paul Simonon and The Verve’s former guitarist Simon Tong. Naturally, Tony Allen would also embark on the Afrika Express tours organized by Albarn alongside a group of African musicians. He also released music on his young British partner’s label Honest Jon’s with Rocket Juice & The Moon in 2012. In short, as he grew older, Tony Allen became omnipresent, feeding his insatiable cravings for new experiences. We hear his signature sound on the records of Oumou Sangaré and Angélique Kidjo but also, more surprisingly, with electronic music alongside Air and Sébastien Tellier. On the “machine music” side of things, he took the experience a step further by teaming up with techno pioneer Jeff Mills for a series of live concerts and an album titled Tomorrow Comes The Harvest (2018, Decca Records).

Having synthesized the rhythms of jazz, soul, funk and traditional Nigerian percussion, he was also at ease when collaborating with a group of Haitian percussionists led by Erol Josué and Sanba Zao for a breath-taking show in Haiti’s capital Port-au-Prince, and on record with – Afro-Haitian Experimental Orchestra (2016, Glitterbeat). All of these new experiences however, never made him forget his love for jazz and Art Blakey. It was in tribute to his idol, whom he had the opportunity to meet at the end of one of his concerts, that he recorded The Source in 2017, released on the legendary Blue Note label. And once again, in tribute to jazz, and in memory of Hugh Masekela who passed in 2018, he completed the work he began with the trumpet player ten years earlier, allowing listeners to conclusively experience the force of the sound Allen collaborated with in the 1970s in Lagos, alongside Fela.

This record (Rejoice, 2020 – World Circuit) in tribute to a late brother is also, to date, the last of Tony’s. “Music is spiritual,” he told PAM in March this year. “If you know good storytelling, music heals. It can do a lot, and it all depends on your mind. In any case, it is infinite. It will remain long after us, and we’re just trying to do what we can to make good use of it when we are lucky enough to find the inspiration.”

These humble words sum up his approach, whether alongside Fela or with others, often younger than him, that the world of music placed in his path.

“What an old man sees sitting down, a young man cannot see standing up.” Sitting at his drum kit, Tony Allen could see from afar. Far enough to be able to recognize the talent of the youngest, even if they were standing up. Laying testament to the truth of this proverb.