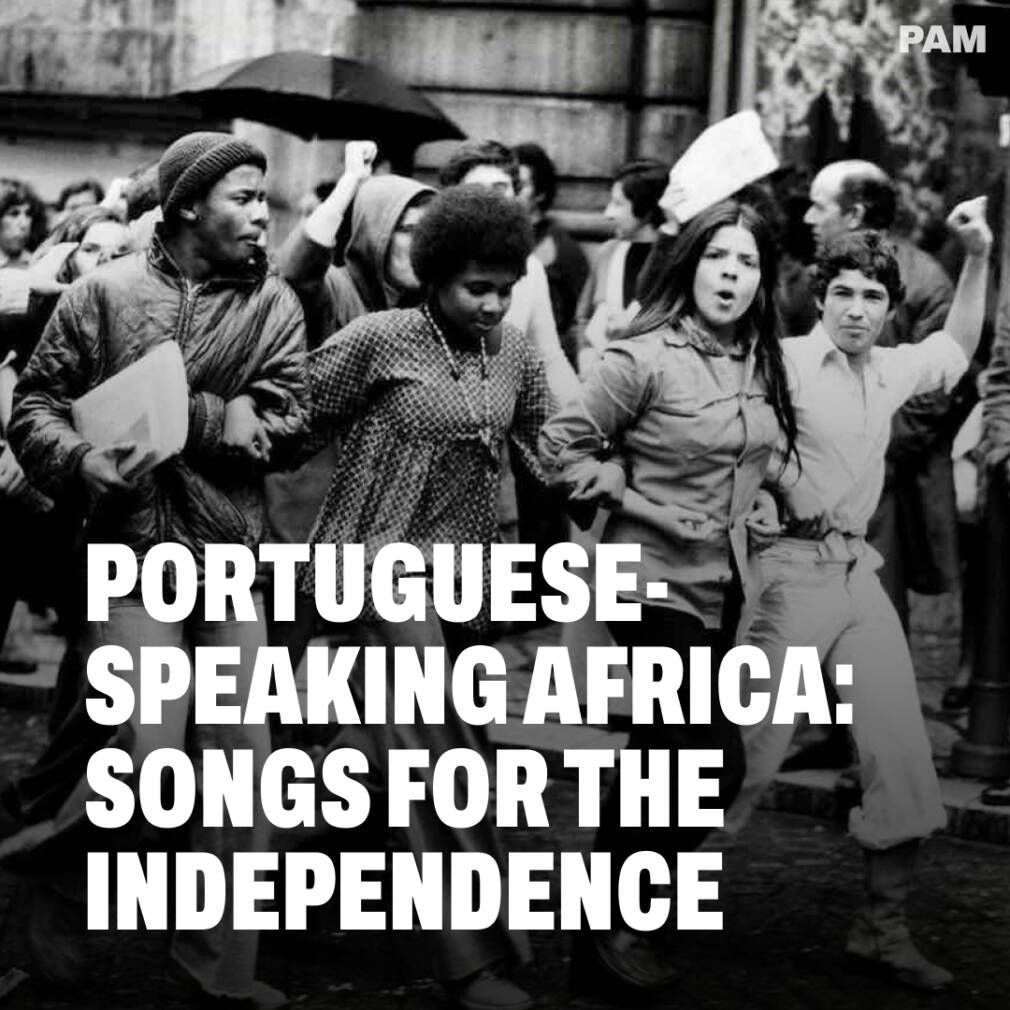

The Carnation Revolution put an end to the dictatorship in Portugal and spelled the end of its colonial empire. From Cape Verde to Angola, Mozambique to Guinea-Bissau, we look back to the soundtrack of the years of liberation. The song selection is available on our playlist on Spotify and Deezer.

April 25, 1974: the Carnation Revolution puts an end to the 41-year Salazarist dictatorship in Portugal. The military coup d’état also spelled the end of the Portuguese empire in Africa. By the time the events of April 25 took place, insurgent movements throughout Africa had exhausted the colonial troops, particularly in Guinea-Bissau, where the guerilla groups led by the PAIGC had liberated large areas of the country. Portuguese youths called upon to fight no longer wanted to die for an indefensible cause. It was in fact young officers who triggered the coup d’état by broadcasting in the middle of the night the song and revolutionary anthem “Grândola vila morena” by Zeca Afonso. And music, in Africa as well, in Guinea-Bissau as in Cape Verde, Mozambique and Angola, amplified the people’s hopes, gave voice to the freedom movements, and galvanized the resistance fighters.

The war against colonialism, through its enormous political and social impact, was the inspiration for numerous songs. Some were linked directly to the clashes or to the daily life of the insurgents, others to the life of simple citizens, in the spirit of “saudade” – the melancholy and longing for their country sung by exiles… All these songs carried critical messages (either hidden or explicitly) about colonization, the reign of terror of the fearsome PIDE (the Portuguese political police also present in the colonies) and the enforced cultural assimilation. All these messages, sung by artists thirsting for freedom who strove to reclaim their culture and their history, contributed to keeping hopes alive throughout the fifteen years of warfare, which finally came to an end with the Carnation Revolution. Here is a non-exhaustive selection of the songs that were the soundtrack to the decolonization process and the years immediately following it.

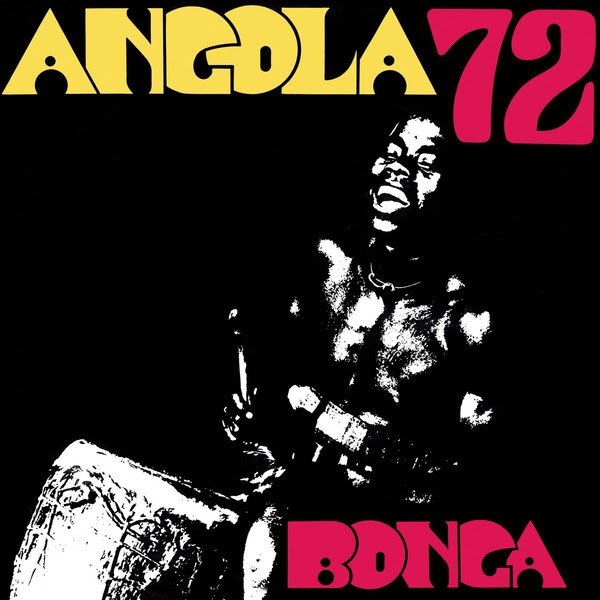

Bonga – “Mona Ki Ngi Xiça” (Angola 72, 1972)

“Watch out, I’m in mortal danger

And I already warned you

She’ll stay and I’ll leave

My child

Cruel men are after her

My child

On a tide of misfortune

God offered me this offspring

That I gave birth too

And she’ll remain here

When I’ll be gone.”

José Adelino Barceló de Carvalho, better known under the name of Bonga Kuenda, “he who gets up and walks”, is one of the greatest voices of Angola. A hoarse voice that is unforgettable. Before becoming the famous singer, the composer of “Mona Ki Ngi Xiça” was already a star athlete in Portugal in 1966. He was 23. With the Lisbon club Benfica he broke the national 400 meter record, which was to remain unbroken for ten years. He took advantage of his fame as an athlete to secretly but actively participate in the anti-colonial struggle, by informing militants and journalists outside the country about the true situation in his homeland. During this period he also performed on stage under the name of Bonga.

Bonga was then identified by the PIDE, and forced into exile. Salazar’s fearsome political police had discovered that the athlete and the so-called Bonga Kuenda were in fact one and the same. He took refuge in Rotterdam, land of welcome for numerous Portuguese-speaking Africans, Cape Verdeans in particular. He recorded his first album there, Angola 72, in eight hours, with Cape Verdean musicians; for the Morabeza label. “Mona Ki Ngi Xiça” – “The child I leave behind” is a song bearing witness to the cruelty of the world. A melancholic plaint about the pain of exile.The album was smuggled into Portugal and Angola in the suitcases of Cape Verdeans and became the soundtrack for the revolutionaries fighting for independence while the Portuguese dictatorship and the colonial regime were collapsing.

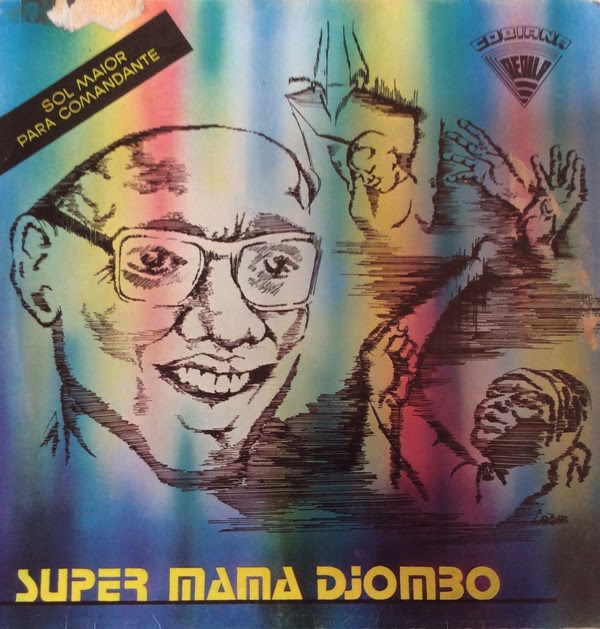

Super Mama Djombo – “Sol Maior Para Comandante” (Sol Maior Para Comandante, 1979)

“Sempri kabesa lantadu, até vitória final!”

(Always the head held high, until the final victory!)

Super Mama Djombo was unquestionably the most popular group in Guinea-Bissau when the country became independent on September 10, 1974. Formed just a year before the event, the fifteen-man orchestra was already highly productive and playing gigs in the outskirts of Bissau, the capital. Their name was taken from the protective spirit the rebel soldiers invoked in the bush: the fetish Mama Djombo. The group played a major role in the modernization of gumbé, a particularly rhythmical traditional style that is found in West African countries, but also in Mandinka music and other popular rhythms of the region.

After the ten years of guerilla warfare fighting the Portuguese forces, Super Mama Djombo sang about the pride of independence and celebrated its hero, “commander” Amílcar Cabral, in the long saga “Sol Maior Para Comandante”. The title track of their fourth album, the orchestra pays triumphant tribute to the man who led Guinea-Bissau to independence, even though he did not live to see it, having been assassinated on January 20, 1973 in Conakry, a year before the day of liberation. A lengthy show of respect and reverence, “Sol Maior Para Comandante” occupies a special place in Super Mama Djombo’s discography, even one abundant in anthems and homages, literally narrating Amilcar Cabral’s life and trajectory. The song is broadcast regularly on radio stations in Guinea-Bissau on the anniversary of the country’s independence, and also when there is a coup d’état (and there have been many since the day of independence).

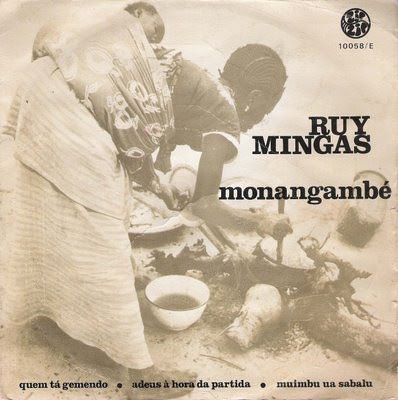

Ruy Mingas – “Monangambé” (Monangambé, 1974)

“The coffee will be roasted

Trampled on, tortured

It will be black

Black the color of the worker”

(…)

“Who makes the corn grow, the orange trees blossom?

Machines

Cars

Women…

And black faces for the motors?”

A nephew of Liceu Vieira Dias, one of the creators of the semba and a member of the legendary group N’Gola Ritmos, Ruy Mingas is a singer, composer and guitarist who has walked in the footsteps of his uncle while also making his own way. Like Bonga, Ruy was a famous athlete in his prime at Benfica. Drawn towards poetry since adolescence, he came across the poem “Monangambé”, which means “worker”, written by António Jacinto. A powerful poem for social and political intervention, it made a huge impact on him.

The words in question tackle the issue of the exploitation of Angolans by the Portuguese in a series of leading questions about the profits the colonists make from their domination. Ruy decided to put music to these crucial words that everyone needed to hear. Sheltered from indiscreet eyes and ears, Rui, who renamed himself Ruy in 1974 to make a symbolic break from Portuguese influences, wrote what became the famous humanist anthem which made him famous. In 1975, after Angola had become independent, Ruy Mingas composed his country’s national anthem, “Angola Avante!”, with Manuel Rui Monteiro. He later set aside his music career to devote himself to politics, and became the Minister for Sport as well as Angola’s ambassador to Portugal.

Teta Lando – “Angolano Segue em Frente” (Independência, 1974)

“This path is difficult

But it brings happiness”

(…)

“This is important to no one

If you are black

But what counts to us is our determination

To make Angola betterA truly free Angola

An independent Angola”

The great Alberto Teta Lando recorded the album Independência in Luanda in September 1974 for Sebastião Coelho’s label CDA (Companhia de Discos de Angola), a year before Angola’s independence. It was the only album Teta Lando released in his country before his exile to Paris in 1979, where he spent most of his career. At the moment the war for decolonization in Angola was fractured by the confrontations between the MPLA and FNLA liberation factions, he sang the hopes of his people on this album, the messenger for the faceless and anonymous, and transformed their sorrows into a message of hope and struggle. “Angolano Segue Em Frente” is that kind of song and perfectly illustrates the desire for union and peace despite the difficulties encountered in order to attain this objective.

Though venerated by the population, and despite the resounding success of the album, Teta Lando was nonetheless threatened due to his proximity to the FNLA, and was forced to flee. Before Angola’s declaration of independence by Augustino Neto’s MPLA on November 10, 1975, he fled to Zaire with his wife and children. He and his family then moved to the French capital, where he died in 2008, only sixty years old.

Teta’s voice is accompanied by the talents of other renowned Angolan artists from popular groups he had chosen for the recording: the guitarists Zé Keno from Jovens do Prenda, Carlito Vieira Dias, son of the founder of the legendary N’Gola Ritmos, Liceu Vieira Dias and Zeca Terylene from Africa Show. And the percussionists João Morgado from Negoleiros do Ritmo, Gregório Mulato from Águias Reais, as well as Vate Costa from Kiezos.

Coral Das Forças Populares De Libertação De Moçambique – “A Unidade” (Hinos Revolucionários De Moçambique, 1975)

“From the Romuva river to Maputo

Against the oppression and the exploitation

The people fight, arms in hand,

Long live FRELIMO and the vanguard

Of all the Mozambican people.”

The Choir of the Popular Forces for the Liberation of Mozambique proudly sings about the people’s newfound unity in this anthem. “A Unidade” (The Unity) is one of the most popular revolutionary songs in Mozambique. It is also a communist-leaning song to the glory of FRELIMO, the Liberation Front of Mozambique. “Our country shall be the grave of capitalism and exploitation” sing fervently in unisson the voices of the choir. This separatist political party was created in 1962 from the fusion of small nationalist groups in various regions of the country to fight against Portuguese colonialism. At the height of the cold war, they opted for the socialist path and received aid from the Eastern Bloc, whose influence can be felt in the mentoring of the young and through the use of culture for means of ideological edification. The Choir of the Popular Forces is the most compelling example. Recorded on June 20, 1975 in the studio of Radio Club du Mozambique, only five days after the country’s declaration of independence, this collection of revolutionary anthems bears perfect witness to the period.

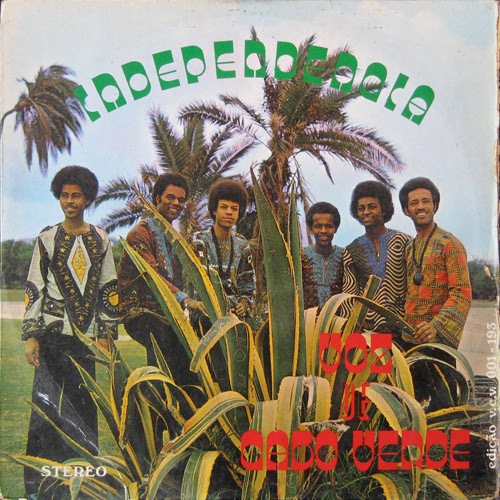

Voz de Cabo Verde – “Combatentes P.A.I.G.C” (Independência, date inconnue)

“Long live Cabral

Long live the fighters of the P.A.I.G.C

Long live freedom”

A Cape Verdean group formed in Rotterdam in the middle of the 1960’s, Voz de Cabo Verde was the first Cape Verdean group to claim themselves as such abroad and to become successful outside the archipelago. Focussing on Europe, “The Voice of Cape Verde” entertained at parties and played concerts where the diaspora met to dance to the stirring sounds of coladeira, but also to the melancholic morna, which would only become popular with Europeans with the revelation of Cesária Évora.

Similar in aspects to an Afro-Cuban orchestra (in addition to Cape Verdean music they played cha-cha-cha or salsa, which at the time was called patchanga), the group was formed by the saxophonist and clarinettist Luis Morais, the singer, trumpeter and bassist Morgadinho, the drummer Frank “Cavaquinho” Cavaquim, the bassist Jean da Lomba, and the guitarist Toy Ramos. They were later joined by another singer, Djosinha, and the organist Chico Serra.

After successive tours crowned by success that led them to France, Portugal, the United States, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau as well as Angola, Voz de Cabo Verde disbanded in 1070. Some of the original members continued to tour under the name Voz de Cabo Verde. It is probably during the 1970’s that they recorded Independencia in Lisbon. The album, inevitably influenced by the independence of the Atlantic archipelago on July 5, 1975, features the song “Combatentes P.A.I.G.C”. It was the iconic José Carlos Schwarz, whose story is told later in this article, who was the composer of this vibrant homage to the soldiers of the P.A.I.G.C over an afro-funk groove with Cape Verdean spices.

Grupo de Acção Cultural – Vozes na Luta (GAC)– “Viva A Guiné Bissau Livre Independente” (A Cantiga É Uma Arma – 1975)

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are now going to sing about Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique And Angola

And the Portuguese and African workers

Brothers in the same struggle against the exploiters

Of Guinea-Bissau, of Mozambique and of Angola”

(…)

“And of Cape Verde

And of São Tomé

And of the island of Príncipe

And of Timor”

In Portugal, the Group for Cultural Action – Voices For Freedom – was a collective of revolutionary musicians and singers that stood out particularly through its engagement against Salazar’s regime. It was formed by José Mário Branco in May 1974, just after the Carnation Revolution, to support the revolutionary movement after the fall of the Salazarist regime. The group’s songs were used for numerous causes, proving that “a song is a weapon”, like the title of their album itself, which was in fact a compilation f their first songs released as singles, such as “Viva a Guiné-Bissau Livre E Independante”. Limpid to say the least, this song is a true indictment of colonialism, committed to the sovereignty of Guinea and other African territories then still in the grip of Portugal. Between 1976 and 1978 the GAC released three major albums (Pois Canté!!, … E Vira Bom, … Ronda De Alegria!!) influenced by traditional Portuguese songs and political slogans They left behind a heritage that quickly set a new standard in Portugal and which continues to have a special resonance today.

Os Tubarões – “Labanta Braço” (Pépé Lopi – 1976)

“Cry independent people

Cry liberated people

July 5th synonym of freedom

July 5th opens the way to happiness

Cry ‘Long Live Cabral’

Honor to the fighters of our lands”

Os Tubarões, which means The Sharks, was a Cape Verdean group formed in Praia in 1969 and led by the late singer Ildo Lobo, who died of a heart attack in 2004. The Sharks, named after the sharks which are often spotted in the waters surrounding the archipelago, were perhaps the most representative group of the music of Cape Verde in the years following the independence. On Pépé Lopi, their first album, released in 1976, they becken the people to raise their voices for freedom with their fist in the air, to the sounds of a euphoric coladeira on the standout track “Labanta Braço”.

The stirring song was the hallmark of the period when the group galvanized audiences and used self-determination to show that the way to freedom was indeed in motion. The group’s bassist, Mario Bettencourt, better known under the name Russo, pointed this out to the Portuguese media Ipsilon in 2015: “This song was the emblem of the period, and for a long time whenever we played it, it caused total hysteria because people had the feeling we were truly heading towards freedom.” Twenty years after the group folded in 1994, ten years after the death of Ildo Lobo, the members of Os Tubarões reformed to tour and played some memorable concerts, such as their appearance at the Atlantic Music Conference in Praia in 2016. The Sharks have left their mark on the history of Cape-Verdean music thanks to their rich and federating repertoire that continues to span generations.

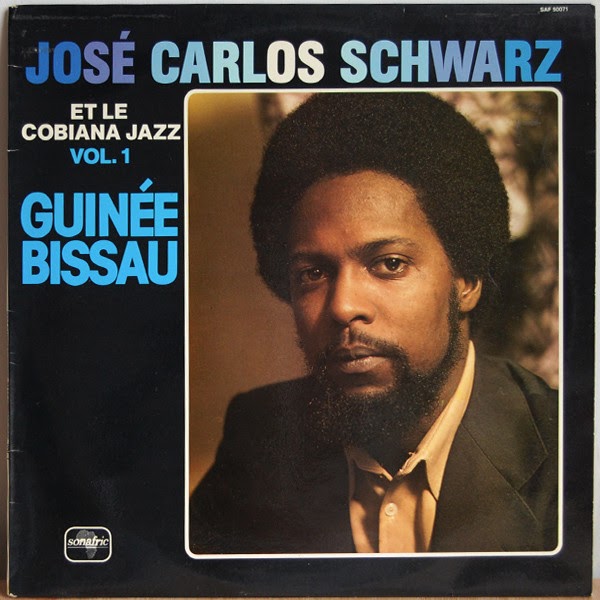

José Carlos Schwarz & le Cobiana Jazz – “Na Colonia” (Vol. 1. Guinée Bissau, 1978)

“Our brothers in Bissau don’t forget us

If you think that we are dead

We are not dead yet, we are sitting here in the colony

One day we will return to Bissau

A day, a day that is long in coming”

Poet and singer indissociable from the P.A.I.G.C, José Carlos Schwarz is considered one of the pioneers of modern Guinea-Bissauean music and a key figure in the fight for the country’s independence. He formed the group Cobiana Jazz along with Aliu Bari and Mamadu Bá e Samakê at the beginning of the 1970’s; it quickly became the most influential group in Guinea-Bissau along with the group Super Mama Djombo. By placing national identity and culture at the core of their music, which was sung in creole, the group played a crucial role in the development of a committed political and social conscience. Driven by the independentist ideals of Amicar Cabral and his right-hand man Filinto Barros, two of the P.A.I.G.C,’s key figures, José Carlos Schwarz became involved in the resistance activities against the colonial powers. During a sabotage operation in the center of Bissau he was arrested and sent to the penal colony on the island of Galinhas, where he was incarcerated and tortured for two years (and which inspired one of his most poignant songs,“Djiu Di Galinha”).

Freed in 1974, this harrowing period was the motivation several years later for the crepuscular album “Na Colonia”, released on the French label Sonafric. His voice full of emotion, he revisited his memories and addressed his comrades in Bissau to tell them that hope was not lost, that he and other prisoners had not died, and that they would one day return home. A happy fate that was not the same for numerous political prisoners, and that this heartbreaking song also emphasizes After the independence, José Carlos Schwarz was appointed Guinea-Bissau’s Director of Art and Culture. In 1977, when his influence and his opinions were seriously beginning to irritate the ruling government, he was sent to Cuba as the chargé d’affaires of Guinea-Bissau’s embassy there. He died tragically the same year in an airplane crash outside Havana. He was twenty-seven years old.

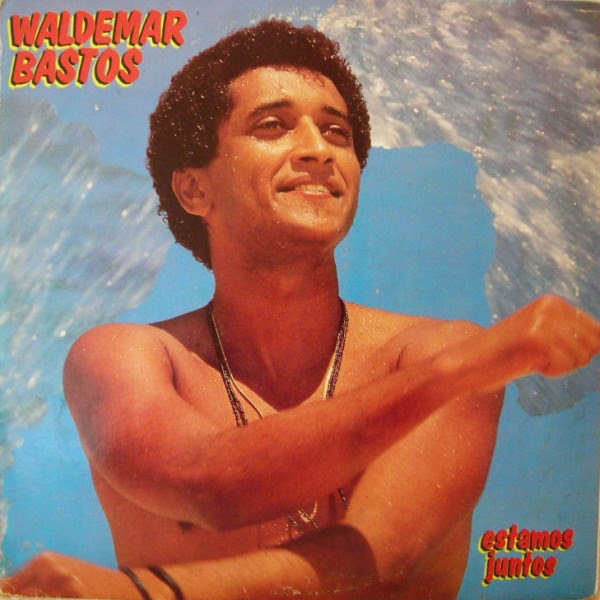

Waldemar Bastos – “Velha Chica” (Estamos Juntos – 1983)

“And we, the school children

We asked grandmother Chica

What was the reason for this poverty

For our suffering

Watch it my children, don’t talk about politics

Don’t talk about politics

Don’t talk about politics.”

The late Waldemar Bastos, who died in August 2020 at the age of 66, had one of the most beautiful voices in Angolan music. Throughout his career, the native of M’Banza Congo sublimated the sorrows of the Angolan people with his quavering voice full of melancholy. Before April 25, 1974 and even before the start of his career as a singer, he wrote “Velha Chica”, the story of an old woman, the “velha chica”, who hides the reasons to young students for the hardships in Angola. “She knew but did not want to give the reason for this suffering.” imply the words. A song that bears testimony, with candor and intense gravity, to the oppressive atmosphere in Angola at the dawn of independence. A time where fear and distrust were part of the daily life of the Angolan people, who “did not talk about politics” for fear of reprisals or of being sent to prison. The song did not become widely available until 1983, when it was finally released on vinyl, the closing track on his first album Estamos Juntos, where he was accompanied by the Brazilian singer-musician Martinho Da Vila. Over the years “Velha Chica” has become a standard of Angolan music and has also been covered by the fado star Dulce Pontes and the singer Maria de Madeiros.

Cesária – “Sodade” (Miss Perfumado, 1992)

“Who showed you this distant way?

Who showed you this distant way? The way to São Tomé

Saudade, saudade

Saudade for my land of São Nicolau

If you write me, I will write you If you forget me, I will forget you

Until the day when I come back”

Certainly, it is impossible to conclude this overview of songs of emancipation of Portuguese-speaking Africa before and after the Carnation Revolution without the eternal “Sodade” interpreted by Cesária Évora in 1992. But long before the barefoot diva, it was sung by the Cape Verdean Armando Zeferino Soares, the composer and first singer of the song in the 1950’s, and by the Angolan Bonga, who touched many hearts and popularized this vibrant lament. But it was without doubt Césaria’s voice draped with melancholy that expressed better than anyone the heart-wrenching history of forced exile to the island of São Tomé. An exile disguised in the form of employment contracts, where numerous “contratados”, Cape Verdeans, were shipped to island in order to be used as cheap labor by the Portuguese on the cacao plantations, in conditions close to slavery.

The song selection is available on our playlist on Spotify and Deezer.