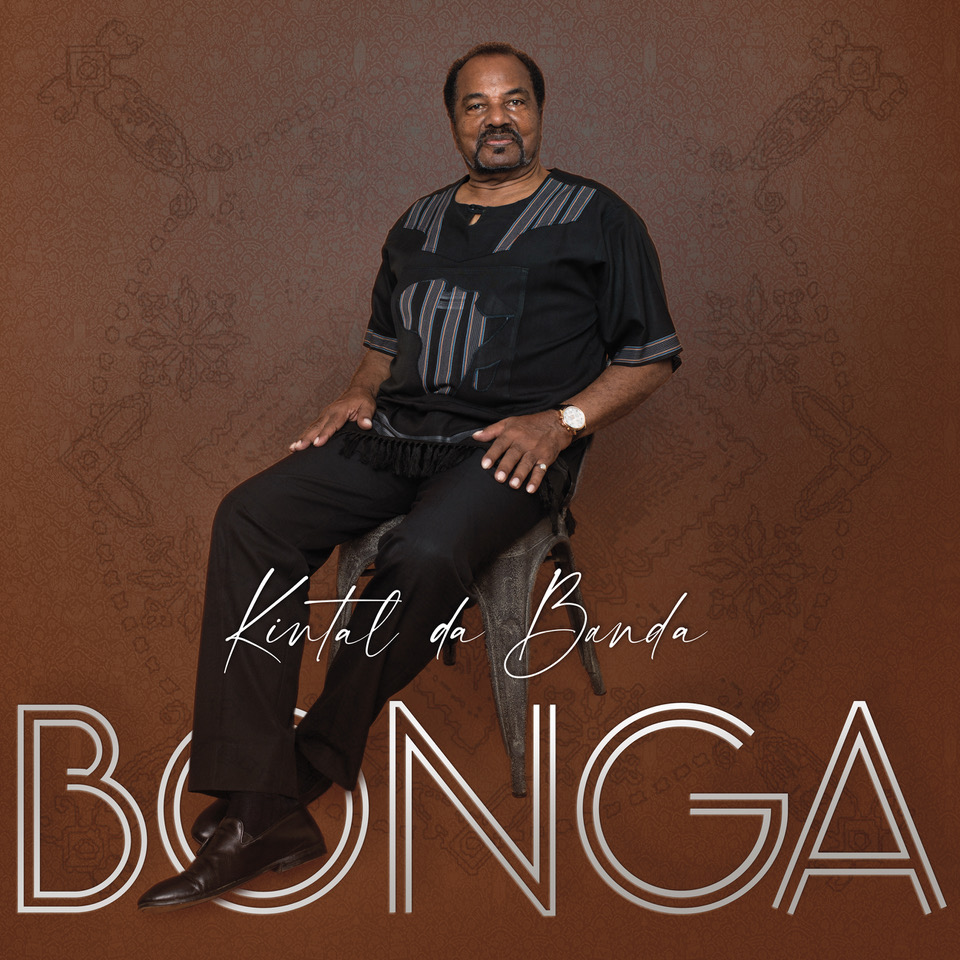

In Angola, Bonga is a legend that successive regimes have wanted to silence. Before singing about colonial oppression, exile, and globalization in over four hundred songs and thirty albums, Bonga was a sporting legend in Angol and champion in the 200 and 400 meter. Thanks to his talent on the track he was able to leave his country (still colonized at the time) for the colonial metropolis in 1966, where he pulverized the 400m in 47 seconds wearing the colors of… Portugal. At the same time, he joined the struggle for the liberation of Angola by using his travels as an athlete to deliver political messages. The dictator Salazar’s fearsome PIDE (International and State Defense Police) caught his fellow comrades in the struggle, but Bonga managed to narrowly escape to Belgium, moving to Rotterdam. It is there that he recorded his first album, Angola 72, with musicians from Cape Verde for the Dutch label Morabeza (reissued since by Lusafrica). His hit « Mona Ki Ngi Xiça » became the anthem of the Angolese independence movement and the album went gold. Still chased by the PIDE, Bonga moved to Paris, where, thanks to the late journalist Rémi Kolpa Kopoul (to whom he dedicated a song), he met numerous musicians, including the singer Bernard Lavilliers. In 1975, Angola gained its independence, but was powerless in dealing with the divisions and rifts of the nationalist groups; followed later by the musical censorship imposed by president José Eduardo Santos. So Bonga decided to remain in Europe which gave him time to cultivate a certain « Saudade », the song that Césaria Evora later covered and turned into a global hit. For over fifty years Bonga has been making us think and dance. For the release of his new album Kintal da Banda, we met with the musical athlete.

You haven’t made a record for a while now. What motivated you to return to the studio at almost 80 years old?

I’m always in demand, even fifty years after Angola 72, my first success! I have always been active, but it’s not every day that you’re motivated and inspired to make an album, even if the music is present inside me 24 hours a day.

I’m a little fed up with the negative turn the world is currently taking, and not only because of Covid. So many other harmful things are damaging us because of the cowardice of the world’s leaders. I haven’t changed, I continue to serve Angolese music and to sing in the name of all those who suffer the consequences of failing socio-political structures. I wanted to address young people. I don’t always want to sing soukouss, rap, or salsa latina: I remain faithful to my musical roots, and I’m proud of it. On this album I’ve had the chance to have wonderful guests like Camélia Jordana. The world of brotherhood is very important today!

How did you meet Camélia Jordana?

On stage! During one of my concerts she came to sing with me. And presto! It was a very powerful moment, which gave me the idea to invite her on this album, and also enabled me to get to know her better. Camélia Jordana is a strong woman, a fighter, aware: she is fantastic! In the studio I said to her, ‘you have total liberty to sing the song ‘Kudia Kuetu’ in your own style.’ And it was perfect on the first take!

This album is very inspired by traditional rhythms?

It’s an album of today, immersed in the traditional, in the rhythms of the Angolese Carnival in particular, with the vocal intonations that the old singers had. I had trouble reproducing it in the studio. Like at the Carnival in Angola with all the dancing rhythms, and yet while being very festive we say serious things like criticizing the catastrophic management by those in power of our natural resources (oil, uranium, diamonds) in Angola.

In this album you evoke personal memories, in particular those of the courtyard where you grew up…

Kintal da Banda, the title of the album, is the courtyard of the house where I grew up. We never lived in buildings. For us, houses always had a courtyard. That courtyard marked me for life! We do almost everything in sunlight: meals, music, sharing traditions, with grandmothers, family and friends. My father wasn’t a professional musician but he sang in Kimbundu and he played the concertina, an accordion, and I accompanied him. Our mother sang us songs in Lingala and in Kabinda, it was wonderful! In the courtyard, the elders were very respected. Even an old illiterate person had a philosophical depth and passed it on to children. We understood later the importance of the courtyard. And today I want to be like those elders: to convey a vision of the world and of tradition. For me, education is taught by singing. It is even more important for children who did not have the same life we had.

The other « courtyard » that educated you was Paris, where you met a lot of different people.

Ah Paris! I love Paris because it’s Paris that opened musical doors for me, like for Cesaria Evora, Manu Dibango, Salif Keita, Mory Kanté, Baden-Powell, Ray Lema… When I fled Angola I ended up in Holland, but it is in Paris that I met the most musicians.

You had to flee your country for political reasons, do you think of returning to live «in the courtyard », in Angola?

It’s complicated for me. When I’m in Angola I’m always on my toes, I have to be wary, I have bodyguards. Before, it was worse, I would go back just for a concert, and I had to be very careful. Some girls wanted to kiss me on the mouth, to put poison tablets in my mouth. Fortunately I’d been warned about this. Ever since the colonial period I’d been stalked. It wasn’t a life, even today in Portugal where I live, I protect myself. I don’t let just anyone into my home, I don’t go to nightclubs, I’m always accompanied, I watch what I eat and drink, etc. You have to have a strong spirit, it’s hard, but when I see the results and the joy it brings people, it’s worth it! It keeps me moving, so there’s no question of retiring.

Kintal da Banda, Lusafrica.