PAM is pleased to present the third episode of the Paris c’est l’Afrique series by Philippe Conrath (1989) via our YouTube channel. A nosedive into Mandingo culture, its griots and its rebels. We meet this time with Mory and Manfila Kanté, Salif Keïta, Alpha Blondy, Nahawa Doumbia…

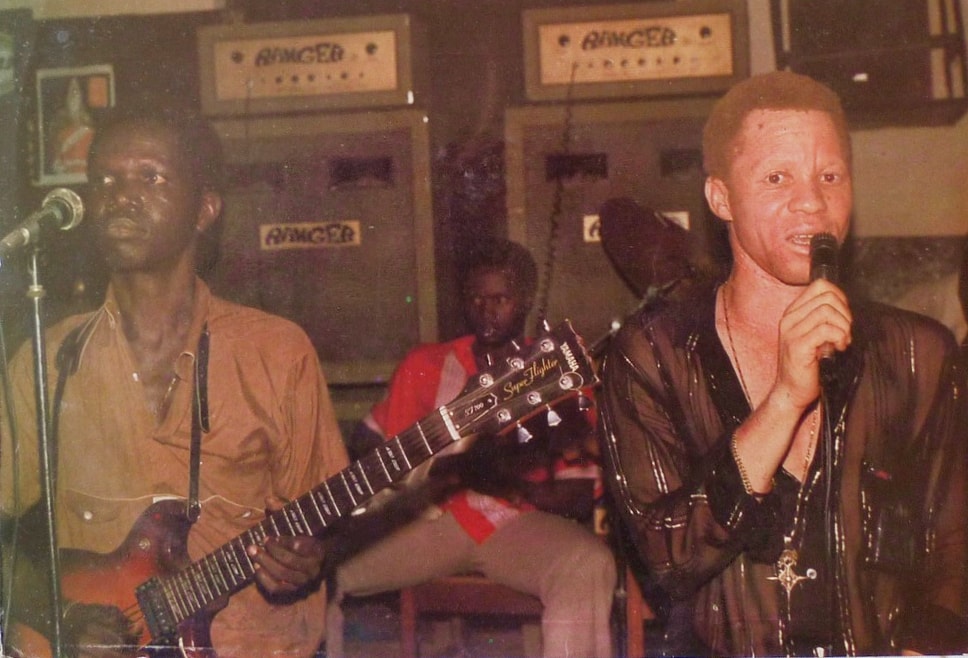

“The whites invented the tape recorder, the television and the radio… but nothing can replace a griot,” says Kanté Manfila, the great guitarist and arranger who, among other things, was a godsend for the band Les Ambassadeurs du Motel de Bamako. In this episode of Paris c’est l’Afrique, he stresses the importance of a lineage of which he and Mory Kanté are the heirs to. Mory then goes on to experience huge success with his song “Yé Ké Yé Ké” all over Europe, holding position at the top of the charts for like, forever. “I couldn’t believe such success was happening to me, an African, a griot…” Mory Kanté says, deeply moved. Almost twenty years earlier, he joined the Orchestre Rail-Band as a balafon player, before replacing Salif Keïta on lead vocals. In the documentary, Kanté Manfila rejoins the rivalry between the Rail-Band and Les Ambassadeurs, pitting griot Kanté’s talent for penning lyrics, against the unforgettable voice of the rebel Salif Keïta. Young Salif was indeed a de facto rebel, as his highborn status made it forbidden to sing or play any instrument – he was a descendant of the Emperor of the Mali Empire, Sundiata Keita.

At home with Salif Keïta’s father, in Djoliba

And then Salif’s father appears on the screen. Rare footage, if not never-before-seen. We are in the village of Djoliba, on the edge of the Niger river, where Salif grew up. His old man, dressed in a traditional hunter’s outfit, equipped with a flyswatter and a gun, recalls the time when Salif “played hide-and-seek so he could go and play the guitar” without his father catching him. A few decades later, Salif is in Paris, and his career is booming. His most recent album Soro, released by Syllart, and arranged by François Bréant and Jean-Philippe Rykiel, achieves huge success. In Paris c’est l’Afrique, he recounts his arrival in France: “I found myself in front of a wall, and this wall was show business. But I had no hammer to break this wall. It was not with strength I needed to break it, but experience and knowledge of this new environment.” And this is precisely what Salif did in Paris, Philippe Conrath reckons thirty years on: “[In Paris] Salif is forced to build a new relationship with time. Here you can’t publish songs longer than three minutes, and ‘Mandjou’ is ten-minute long!” On screen, Salif continues: “Here, you have to get to the crux of the matter quickly. You end up learning things that can be useful for you, and you can take them back home. If you have both [the Mandingo tradition and this Western way of working], then it’s great!” The same motive brought another rebel to the French capital. His name: Seydou Koné, aka Alpha Blondy.

Abidjan and Bougouni two neighborhoods in … Paris

He came into Paris in the same way as he’d step out in Marcory – a suburb of Abidjan –, with the possibility now to step back to escape a country where he was already too famous. And the philosopher who has a way with words tells us this is what crossbreeding is. A reality that France took a long time to come around to – if it actually ever did: Blondy is a “cultural mestizo”, made up of multiple identities each with their own languages – French, English, Malinke. He is all of this at once, and he likes to say he conjugates “the verb ‘to be Alpha Blondy’ in the first person”! His words are accompanied by the video for “Sweet Fanta Diallo”, shot in France, and you can still feel the enthusiasm shared through the screen.

The film ends in Bamako, at the home of another rebel, this time hailing from the Wassoulou region. We arrive in Bougouni, in the Sikasso region, in the south of Mali. We visit Nahawa Doumbia, the female singer who, like Salif, was not permitted to sing. What a shame this would have been. Accompanied by a guitar, surrounded by a group of kids, she presents the film with its conclusion and a moment of grace. Not long after, she would be producing with Cobalt – the label that Philippe Conrath revived in 1989, a few months before founding the Africolor festival.

In 2019, for Africolor’s 30th anniversary, Conrath rediscovered the footage he had buried in a dark corner of his mind, and told PAM: “When I watched these again, I realized that this is my whole life. These musicians, this culture and this music established my profession, and helped to create my business. It is thanks to Mory Kanté that I set up my company, Cobalt, because he had asked his editor Francis Kertékian to give me a percentage of “Yé Ké Yé K锑s publishing rights, as a thank-you for a favor I had done for him. I didn’t have to take on a debt to launch my label: my bank was Mory Kanté!” Can a griot finance a rebel?! To achieve these kinds of results, you have to operate on the renewable energy of human interaction. And that’s the same energy you feel running through Paris c’est l’Afrique.

Discover Paris c’est l’Afrique‘s other episodes:

- The Pioneers

- The Many Ways of Mbalax

- The Griots and the Rebels