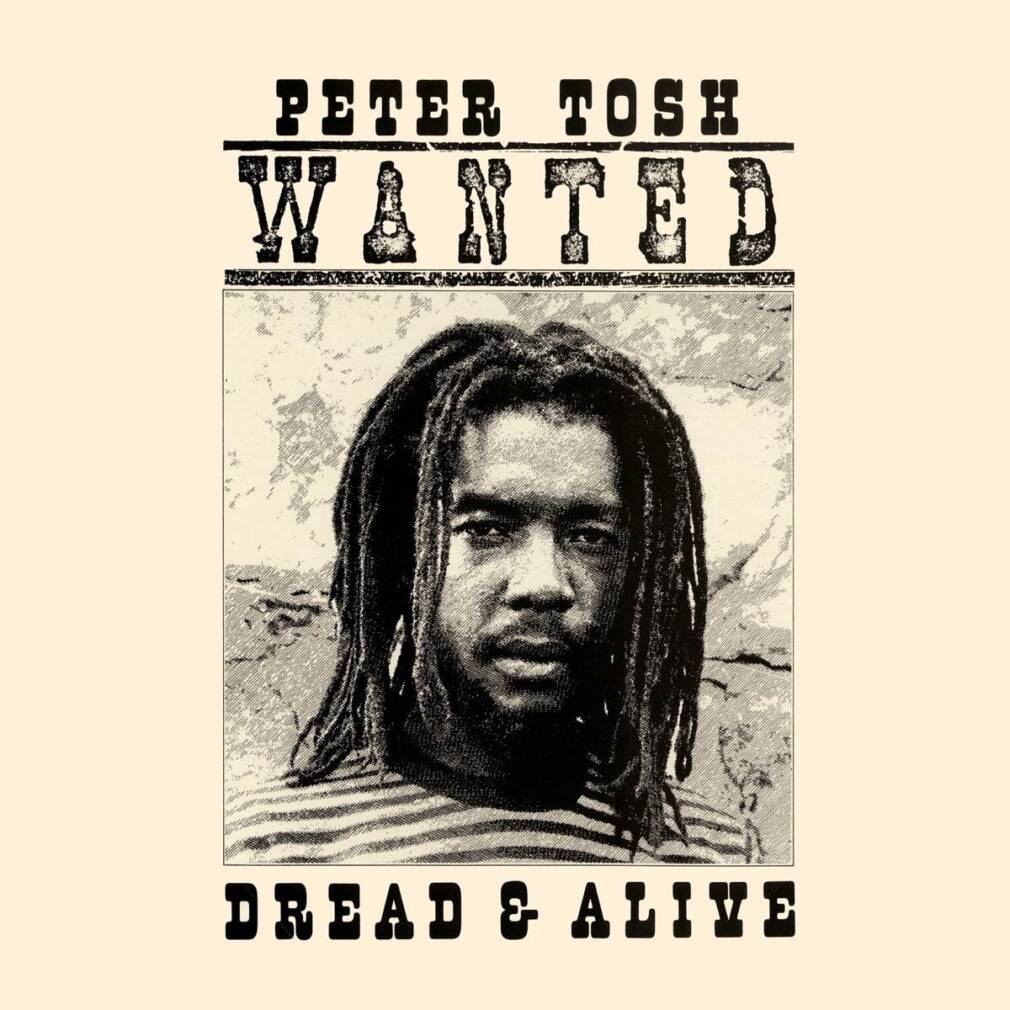

The murder of an artist often precedes the end of an era, the brutal and visible putrefaction of the soil of the years that made the success of this much admired legend but which also crystallized protean hatreds. It turns sour, and the icon fades mercilessly. Peter Tosh was murdered surrounded by his friends, at his home, by ghetto thugs that he himself had rubbed shoulders with… Marley’s posterity has often overshadowed his own.

As with the murder of other popular black figures (Sam Cooke, Tupac, Lucky Dube, Malcolm X and others), a murderer is identified, but the real case is often more complex and shrouded in silence.

The death of Peter Tosh, in a way, sums up his life; an artist who often sang about the ghetto, who fought all his life, including just before he died, and who still wondered, in “Fools Die”, why kill your own brother? “Tosh was like Malcolm X, you could feel those vibes when he spoke! He was a revolutionary, he had too much power for some, he was disturbing,” summarizes the dub poet Mutabaruka.

Jamaican Nightmare

On September 11, 1987, in the twilight of his last hours on earth, Peter Tosh had become a star. He toured and recorded with the Rolling Stones, he went to Africa to sing, he saw witch doctors and healers, and the ex-Wailers moved to the chic Barbican district in Kingston. Far from the ghetto.

That evening was spent with his wife, Marlene, and friends, including musician Santa Davis, Milton Brown and Michael Robinson. The singer heard dogs barking. Robinson is sent to check the door. Three armed men manage to enter the property. Among them is Leppo, an old acquaintance whom Tosh had helped after his release from prison where he had been sent for murdering a policemen.

Rumors say that the famous Leppo came regularly to ask Tosh for money. Peter Tosh seemed to fear no one. He was often brutally beaten up by the police, he was a martial arts fan and would hold up his machine-gun guitar and spliff without batting an eyelid in front of the audience. He was very articulate, but he always explained that he lived with a fear, the fear of evil and of the famous duppies, those evil spirits, which he talks about in his autobiographical tapes that will become the material of the film Stepping Razor.

But that evening, the threat was human and palpable: the gunmen asked him for money. At this moment, the host Free I Dixon (with whom Peter Tosh had then the project to create a rasta radio) and his wife arrived. The aggressors opened fire and killed Tosh, Free I and Milton Brown, and seriously wounded Santa Davis.

Shortly afterwards, Leppo surrendered to the police, he escaped the death penalty but never revealed the names of his acolytes and in the end declared himself innocent.

“In those days, with what we sang, you could expect anything from anywhere,” said Bob Marley, after miraculously escaping mysterious assailants who came to shoot him in 1976 after he supported the campaign of Prime Minister Michael Manley. Tosh’s assassination also came in the midst of a tense election campaign. “Jamaican society was not yet ready for Rasta ideas to be broadcast on radio,” explains Joy Dixon, Free I’s widow, in the film Stepping Razor, which recounts the creation of Rasta radio.

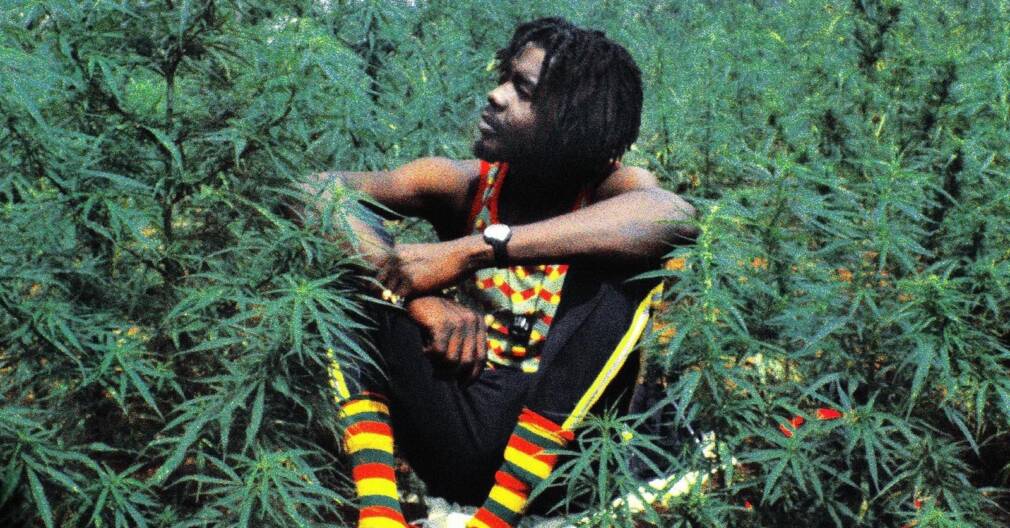

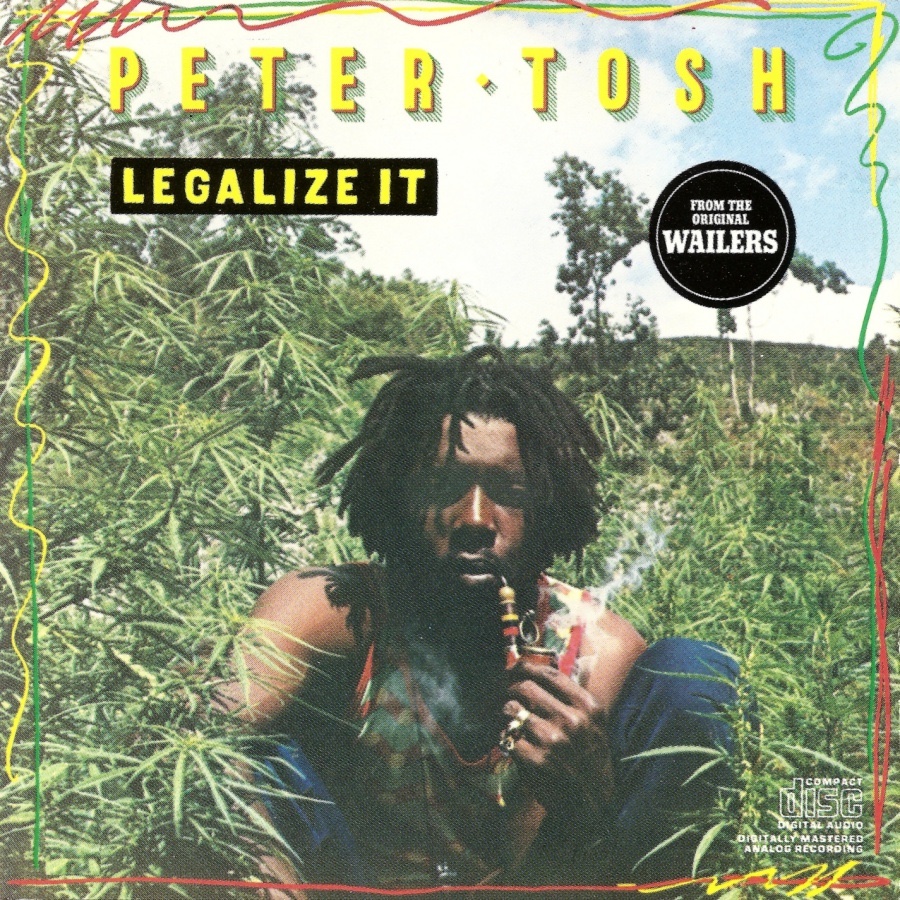

Since the death of Tosh, the author of the hit “Legalize It”, Jamaica has indeed changed: Irie FM has become an official reggae radio, and since 2015, weed is legalized, we no longer smoke the varieties sensimilla or “goat shit” that Tosh liked, but the American Dream or Amnesia Haze.

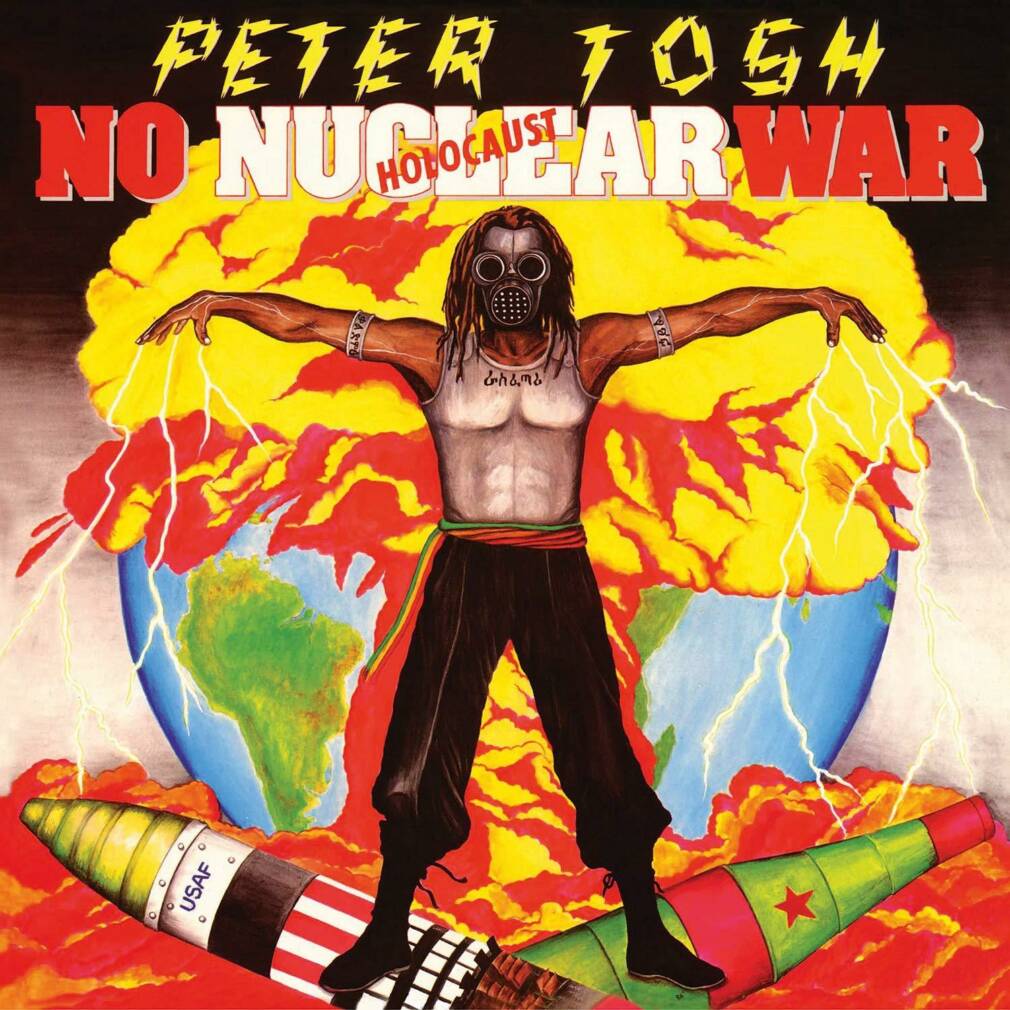

Legalize It

Yet Peter Tosh had a hard time recording his first solo record, Legalize It, whose famous cover shows him in a grass field. “We struggled to make the first record without money,” says Lee Jaffe, cover artist, producer and musician. “It wasn’t easy to find partners or a label because people were afraid of Peter.” It was 1976, Marley was on the rise, but Peter Tosh was struggling to get his solo career off the ground after leaving the Wailers. It must be said that he remains, even today, associated with Marley, whereas he is also an immense composer and the author of several hits of which the famous “Get Up, Stand Up”. He always said that he had learned the guitar from Marley, his younger brother.

Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer and Marley had many things in common: they were all young country boys who had come to the capital to find themselves, or get lost, when they met, on the outskirts of Kingston, in Trenchtown. All of them had grown up without a father and they were soon taken under the wing of some Rasta mentors like Joe Higgs, Vincent Tata Ford, Mortimer Planno, who helped them shape their musical talents and contributed to make the Wailers the historic trio that it became. “Together, they were a real family, and they all had real family ties, which bonded them and surely helped them develop their art!” explains Neville Garrick, author of many Bob Marley and the Wailers covers.

Simmer Down

Their hard work paid off in the early 60s, when they were young and clean-shaven. After a successful audition for Coxsone, the Wailers recorded their first song at Studio One. “The first time I met Bob, Peter and Bunny, I was working with the Skatallites on Brentford Road at Studio One,” said the late trumpeter Johnny Dizzy Moore. “We saw that there was something unique about these young people. In those days we didn’t rehearse the songs themselves, we played harmonies, scales, learned how to distribute notes and ideas and then injected all that into the music. I think it was this method that made the music so unique because there was a personal touch to the sound.”

The Wailers’ first recording became a hit a few months later. Recorded in December 1963, it reached number 1 in February 1964. The song is called “Simmer Down” and is already a call, perhaps prophetic, from Tosh to those who live by crime …. This first success intersects well with the themes that will be dear to Tosh and Marley: spirituality, the revolution and the expression of discontentment of the poor districts.

On the advice of Studio One boss Sir Coxsone, the Wailers changed their name from the Wailin’ Rude Boys to the Wailin’ Wailers so as not to be lumped in with the thugs.

But since then, Jamaica’s inner-city roughnecks have become gunmen as their artillery has grown heavier and their violence has continually pushed the human envelope and run amok in annual homicide statistics. Like these criminals, Tosh, the Stepping Razor, nevertheless always lived on the edge, rejecting what he called the “Shit-stem” and the establishment. He died on his feet, alongside the common people he always defended: dignified rudeboys, gunmen and wailers.