Whatever its shape, the flute stands firmly rooted in most African music. This is an insight into the role of the instrument, with a focus on the musicians who made it famous and those who place it in the spotlight today.

The n’dehou

Cameroonian citizen Francis Bebey who passed away in 2001, began his professional career as a radio journalist and diplomat before dedicating the rest of his life to music – he even went on to receive a resounding popularity in the 1970s with humorous songs such as “La Condition Masculine” [a French expression for “the male condition”, ironically mirroring contemporary concerns of “the female condition”; translator’s note]. The son of a pastor based in Douala, Bebey grew up listening to Bach and Beethoven, classical guitar, jazz music which he introduced to Manu Dibango, as well as the natural rhythms of the rain, the sanza – his favoured instrument – and Pygmy music which his father had forbid him from listening to. It was however from the Pygmies that Francis learned how to play the n’dehou, a bamboo pocket flute that created bird-like sounds, which the musician performs with in a call-and-response improvisation accompanied by the unique highly-pitched vocals of the Pygmies. “Just because they live in the forest does not mean they are uncivilized people,” he said. “On the contrary, they are highly intelligent people. They invented this amazing musical technique where they can hold conversations with their own instrument.”

Driven by a strong appetite for experimentation, Francis Bebey explored the vast potential of synthesized sounds, in producing a never-before-heard fusion of traditional and electronic music, compiled posthumously by Born Bad Records in the two excellent albums African Electronic Music 1975-1982 and Psychedelic Sanza 1982-1984. In the songs “Bissau” and “Sunny Crypt”, it is evident that Francis Bebey has always cherished the n’dehou. In 1982, he placed the pygmy heritage into the spotlight even further, with the record Pygmy Love Song. Following in the footsteps of his father, Patrick Bebey now carries the torch of the sound smuggler, which led him to playing the pygmy flute on “Everything Now”, Arcade Fire’s worldwide hit in 2017.

The sodina

In Madagascar, the great master of the sodina is Philibert Rabezaoza aka Rakoto Frah. At a young age he was introduced to the flute of Malagasy – the sodina –, which is traditionally accompanied by the vahila zither, the amponga drum and the kabôsy lute to perform hiragasy music. The luthier-musician hosted festivals and rituals of the Merina ethnic group, before founding the band Feo-Gasy with Erick Manana and recording several albums, including Flute Master of Madagascar in 1988 and Souffles de Vie in 1998. Ornette Coleman spoke of the Malagasy master as having some of the most beautiful musical phrasing in the world. His elegant technique was likewise admired by Paul Simon, Manu Dibango and Ladysmith Black Mambazo, with whom he toured alongside for a long period of time, presenting new horizons and prestige to this noble instrument from the highlands.

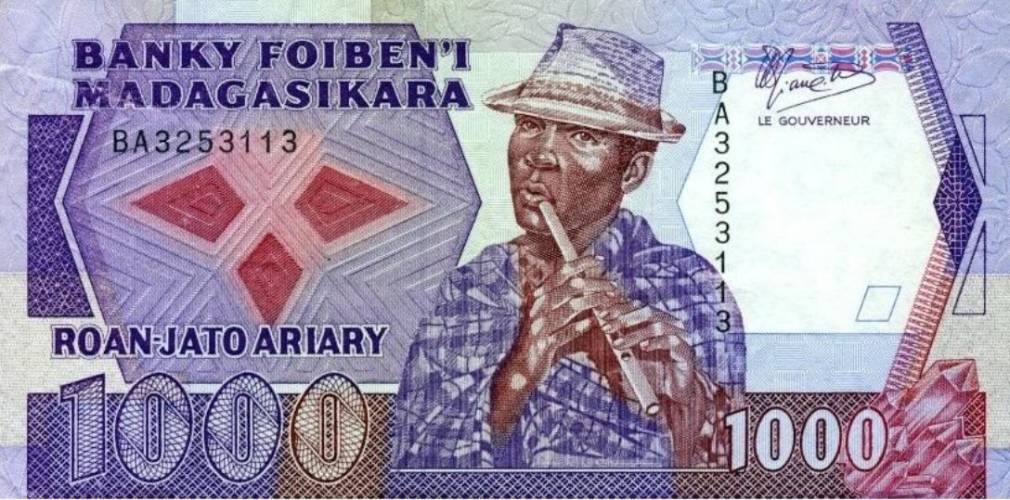

Despite his popularity – which included being immortalised onto the face of the 1000 Malagasy franc banknote; as well as being selected to be the official ambassador to welcome French president General Charles de Gaulle to the island in 1958 – Rakoto Frah made sure to pass his artform down to the youth according to Camille Marchand, who directed a beautiful documentary on this legacy. He teaches them how “the ear and the breath awake the sodina, a tiny piece of bamboo, metal or PVC, with six holes in it and no mouthpiece”. Saxophonist and teacher Nicolas Vatomanga, who was well-trained at Tony Rabeson’s school, infuses his sodina with explosions of free jazz and oriental inflections, whilst preserving “the great warmth and deep wisdom led by the masters of this tradition”.

The tambin

“The sound of the Peul flute is just so captivating… Like the water that quenches your thirst, it is also a proclamation that soothes and awakens: it is a kind soul. Between the flute and me, there’s a loving relationship,” says the Paris-based Dramane Dembélé who, much like his fellow Burkinabé musician Simon Winsé, feeds from the heritage of great masters of the tambin, from the French capital. Originally from Fouta-Djalon – Northern Guinea’s highlands –, Mohamed Saïdou Sow is one of these aforementioned masters and although he may not be a typical shepherd – in contrast to the regular tambin players – he is well and truly Peul and a luthier-musician who possesses the well-kept and fabled secrets of the master flutists.

Rather than being tied to this deep-rooted ancestral tradition, other virtuosos such as Aly Wagué preferred to fluctuate back and forth inside the Mandingo world, offering his breath to an assortment of musical legends, including Mory Kanté, Baaba Maal, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Sixun and Malian keyboardist Cheick Tidiane Seck – with whom he recorded the opening track for Sarala, produced alongside North American jazzman Hank Jones in 1995. The Peul flute unveils its charm on “Tounia Kanibala” in particular: Aly Wagué merges his voice with the breath of the instrument for an incredibly frenetic improvisation. Amongst the “crazy African jazzmen” (read the series PAM dedicated to them here), many adopted the tambin into their music, such as Eric Dolphy, Don Cherry and flutists Buddy Collette and James Newton, opening up new frontiers for North American jazz music and its future.

The gasba

Before becoming the undisputed queen mother of raï music, Cheikha Rimitti performed in the cafes and cabarets of the Algerian underground in the 1940s, using her hoarse vocals to sing unashamedly of love, pleasure, social misery and drinking habits. Brought up with the tradition of rural chants, Cheikha has always been accompanied by the ancestral guellal drum, as well as Cheikh Ould Ennems on the gasba – the long reed flute of the Berber people, whose precise tonality she was accustomed with since childhood, having been brought up closely alongside Bedouin traditions.

An essential accompaniment to the popular songs of the mêlhun, the gasba flute can induce trance through a circular breathing technique used during religious ceremonies. This technique paved the way for “electronic trance” music, as heard in the works of Moroccan producer ڭليثر Glitter٥٥, Sofiane Saïdi & Mazalda, Acid Arab, as well as in Brian Eno’s excellent “New Feet” and, more surprisingly, in the compositions of Hungarian pioneer of ethnomusicology Béla Bartók. Alongside the many that like to sample, perform on stage or study the gasba’s expandable and mysterious timbre, others have tried to reproduce it: such as Tunisian musician Nidhal Yahyaoui who, in 2007, he undertook research in situ of a vast collection of tradition songs and music from the mountainous region of Bargou, “the region of the outcasts and the poor,” he likes to specify. Teaming up with Ammar 808 and the band Bargou08, this self-proclaimed “pop music front” went on to release Targ (Glitterbeat) ten years later: Moog keyboards, bass and drums share the beat with the loutar lute, the bendir, the zokra oboe and the gasba flute. Their mission? “To make people proud of their region again,” tells Sofyann Ben Youssef.

The ney

Although the ney appears in Ancient Egyptian funeral art, the Persian-born mystical poet Djalâl ad-Dîn Rûmî is a key figure for this oblique flute, of which he praised the transcendental nature and infinite nostalgia of in many of his poems, from as early as the 13th century. Following his lead, the Sufi Mevlevi order would practice the samā, a spiritual concert where whirling dervishes perform mystical dances to the sound of the ney, the daf tambourine and the tanbur lute, in search of divine union. “Rûmî is at the center of the sacred mythology of the ney. To his ears, the instrument is the sound of the soul – there is nothing closer to the voice of God. The sound of the ney is more wild, primitive and natural than that of the flute. When you play it, you are the wind inside the reed. It is truly wonderful,” confesses musician Naïssam Jalal.

Born in Paris to Syrian parents, Naïssam grew up in a diverse cultural breeding ground, where she fell in love with the time-honored role and breath of the flute – “Look at Krishna, it’s not the drums he’s playing” –, persuading her to follow in the path laid before her. “My relationship with the ney is that of a migrant child led by their roots: it’s the instrument of my ancestors,” – an instrument she then decided to study at Damascus’ Arab Institute of Music at the age of 19, and which she upholds today in some of her compositions, which are fused with spiritual jazz and indignation. Frequently guesting in traditional music as well as instrumental “art music”, often in the shadow of the oud and the violin, the ney has also appeared as part of orchestras, notably alongside the great Oum Kalthoum. “Unlike the Egyptian kawala, whose roots are rather rural, the ney conveys a certain nobility, as it is regarded as an instrument of the elite,” explains Naïssam Jalal. “However, in Syria and Palestine for example, before keyboards replaced the real neyetis [ney players; author’s note], the nay was also played in highly festive contexts, such as weddings. The ney is the true unifier [between the various parts] of the Arab world.”

The washint

In 2018, Ethiopia lost one of the world’s most distinguished washint players, Melaku Gelaw, followed closely by Yohannes Afework who passed away the following year. These two masters of the Ethiopian flute, traditionally played solo by shepherds of the Abyssinian highlands, forged the golden age of the genre’s pentatonic melismata within the Orchestra Ethiopia in the ’60s – to which Francis Falceto’s Éthiopiques compilation series dedicated its 23rd volume. They were men of their time who were not afraid to lose themselves to Swinging Addis’ funk, rock and soul-infused fever, by lending their breath to Alèmayèhu Eshèté, Tlahoun Gèssèssè and Mulatu Astatke who, much later on, would lead Yohannes Afework’s washint towards a more bop, Latin and Coltranian jazz sound with Sketches Of Ethiopia released in 2013.

Following Derg’s dictatorship, its fall, and from the late ’90s the consequent rediscovery of the bottomless pit of grooves created in the ’60s, musicians from all walks of life today have breathed new life into these traditional hypnotic rhythms, and sometimes unto their own creators. Such is the case with France-based Arat Kilo and Akalé Wubé, the latter giving prominence to traditional instruments, including the washint in “Addis Ababa Bete”, while in Ethiopia however, things have taken a more electronic-oriented turn. Producers and pioneers of “Ethiopiyawi Electronic”, Mikael Seifu and Endeguena Mulu (aka Ethiopian Records) combine traditional folk sounds with the rhythms of UK garage, house and post-dubstep, sampling the instruments of the azmaris (traditional bards that still continue to perform in the cities’ cabarets) to turn them into pounding-beats for the dancefloors of Addis Ababa’s underground clubs – performed live, as seen at the Festival Banlieues Bleues with Ermias Nadew at the washint, is also most definitely worth checking out.

The toutoun’bambou

Politically focussed, resistant, identity-affirming and most definitely Creole, the gwo ka is to Guadeloupe what the maloya is to Réunion. In both cases, it is their profoundly African roots and their links with slavery that have often been criticized by the assimilated polite society. The gwo ka is named after the drum that marks the seven rhythms of its pulse, and the bamboo flute that accompanies it – which some say was inherited from the Peul flute – makes it one of the key ingredients to the recipe. It’s the reason why you hear it today in its various formats – wooden or transverse – in the modern mutations of gwo ka: revolutionary for Gwakasonné, fusion-styled for Olivier Vamur with the band Horizon, augmented for Magic Malik, or even serving as a cultural link for Kimbol, where flutist Célia Wa (listen to her superb solo in “Adan On Dot Soley”) made her debut under the direction of tambouyé-drummer Sonny Troupé. Both artists would meet again later in Expéka Trio with female rapper Casey – of Martinique descent – with the aim of giving a voice to the suffering Antilles society, through a unique fusion of rap, soul and gwo ka.

An ardent defender of Martinique’s musical heritage, and of the chouval bwa in particular (the music that traditionally accompanies hand-operated carousel horse rides), Dédé Saint-Prix likewise does not refrain from concealing his love for the bamboo flute that he’s played since the 1960s as a way of softening his activist outrage. From one island to another, this bamboo flute has indeed passed around the “breath of life”, an expression invented by Max Cilla, father of the flute from the Mornes region – steep mountains where the French Antilles’ Black Maroons called Neg’Marrons found refuge in after fleeing the plantations. After a few years living in Paris, Max Cilla chose to return to his native country to craft his toutoun’bambous, then played only by elders in the countryside, and almost forgotten about at the time. On the impetus of Aimé Césaire, he instilled the heritage – in particular to Eugène Mona, another Mornes-born Creole poet and flutist –, however Max Cilla also performed a “contemporary traditional music” as recorded on La Flûte des Mornes. Released in two volumes that carry both the soul and the memory of his island, the album has been a cardinal landmark for West Indians in search of their own identity. Born to Martinican parents, Christophe Chassol too would come to revisit his ancestors’ journey by creating Big Sun (2015, Tricatel), an “Antilles Space Odyssey” where you can hear, amongst the sounds of birds and seashells he collected on a road trip, the flute of Mario Masse played on two of the most stunning tracks of the record.