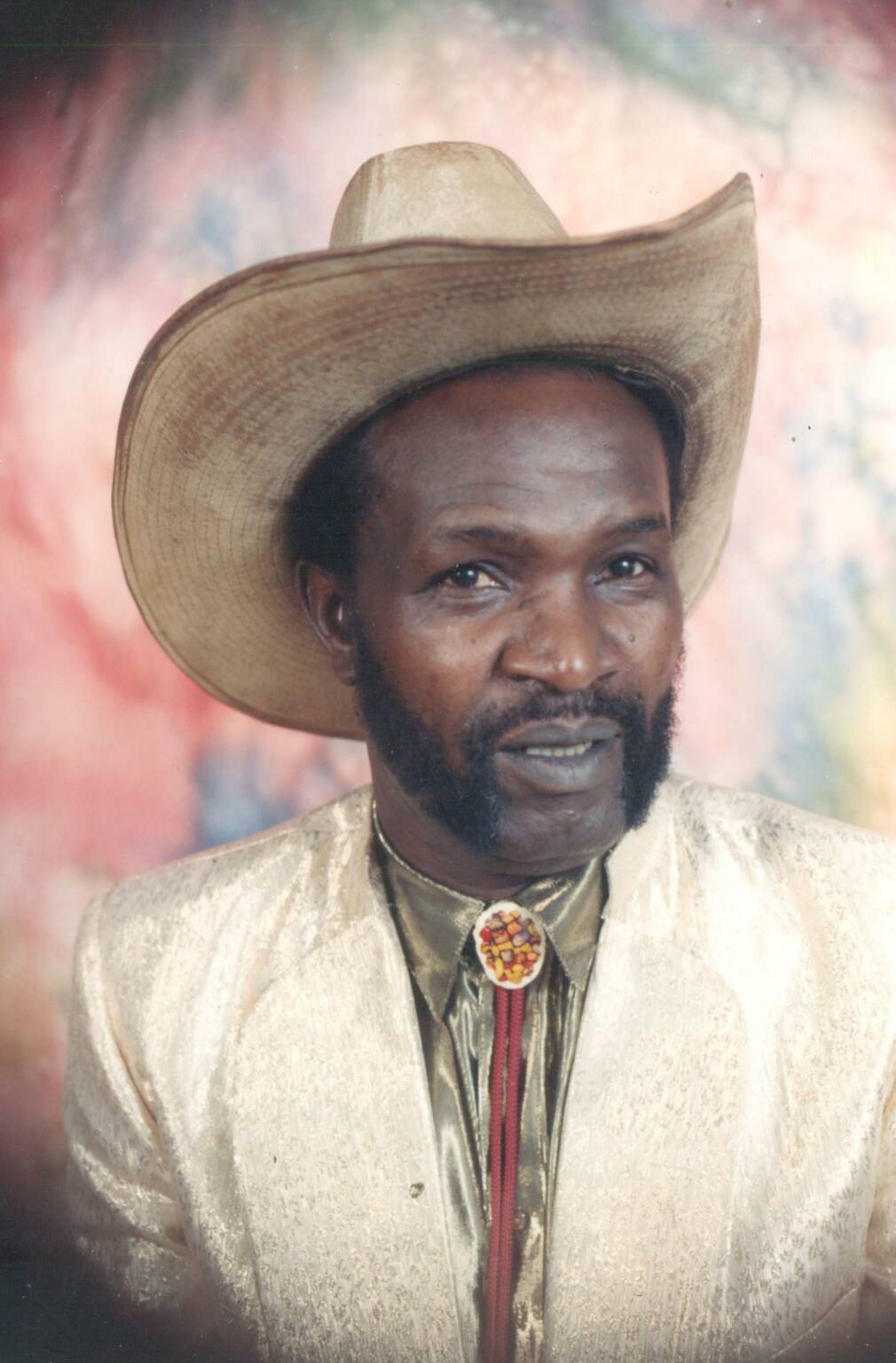

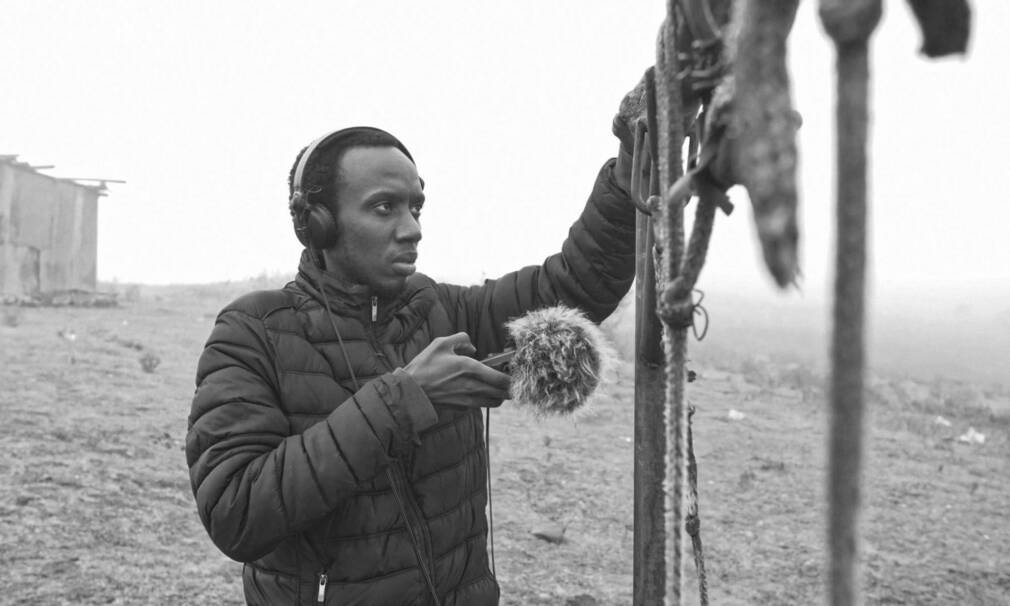

This is a tale of two Joseph Kamarus. One a giant of Kenyan folk, history, and politics, outspoken and festive, energetic and upfront. The other, an ambient electronic pioneer, reserved and delicate, modest and thoughtful. The two are bound by name and blood, but separated by two generations, a separation which has brought nuance to each’s sensibility, relationship to the world and use of technology. While Joseph senior worked in Kikuyu proverbs and played from the pulpit of political campaigns, KMRU (Joseph the younger’s moniker, which we’ll use for simplicity sake) is deft in the ways of digital audio workstations and sound samples, making quiet headway as a student in Berlin and Ableton workshop teacher in Nairobi.

Despite differences, the silent hand of destiny joins the two together, each a different octave on the same musical staff. There was an “inherent connection,” KMRU recounts, “and I think it’s because I was directly named after him.” We spoke with KMRU about his relationship with his late grandfather, trying to find the similarities in the vast differences including how KMRU thinks of his grandfather’s legacy as he works to reissue his music to the world.

Gucokia rui mukaro (returning the river back to its course)

“When I was in high school and maybe in primary school when I would mention the name Kamaru people would ask if I was related to ‘the Kamaru’.” KMRU explains via a Zoom call from his Berlin residence. “I didn’t know he was a musician or a famous person. I just knew him as my grandfather. It made me realize that my grandfather was somebody who was important and I should consider talking to him more and getting to know more of his work.”

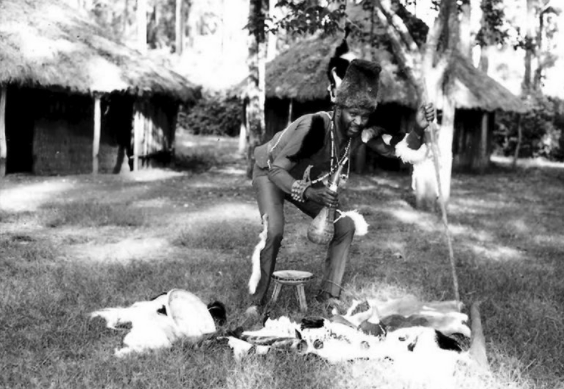

“The” Joseph Kamaru, who passed away in 2018, was Kenya’s best known folk singer. Combining benga, jazz, and Congolese soukous music with Kikuyu (one of Kenya’s largest ethnic groups) proverbs, Joseph Kamaru wrote songs that cut through the political elite and mounted a broad social commentary for a post-colonial Kenya. Growing up in a working class family, Kamaru first entered the public zeitgeist with his 1966 single “Darling ya mwarimu”, telling the story of a young girl who was sexually abused by her teacher. After the song’s release, the Kenyan National Union of Teachers (KNUT) called a nationwide strike, sparking parliamentary debate and necessitating the intervention of then President Kenyatta.

Kamaru’s polemic beginnings continued on for years, attacking taboo subjects like corruption, rape, and later in life, God. “Tiga Kuhenia Igoti” (Don’t Lie to the Court), another landmark track from Kamaru’s vast catalog of over 2,000 songs, condemns a man on trial for rape by embodying the voice of the victim. Then there’s “J.M. Kariuki,” which turned Kamaru’s presidential ally and friend into a political pariah. The song was written when a former Mau Mau detainee and a popular member of parliament, Josiah Mwangi Kariuki, popularly known as JM was found murdered in Ngong Forest with his body mutilated. “J.M. Kariuki” not only describes the grisly murder, but also asks the government to provide the answers to the death of an innocent man (KMRU). Or consider his outburst during the 1992 Madaraka Day celebrations when Joseph took the microphone in front of a stadium of people to address then President Moi directly, “Don’t sit comfortably with your fimbo (club). I know there are people telling you that you are popular, but the truth is that people do not like you.”

Joseph the senior was not only a maverick for his bold discourse, but for his knack of combining benga music on guitar with the Congolese finger-style, and the folky swag of his American analog Jim Reeves. The songs are at moments funky, at others meandering, and at all times totally original. Joseph Kamaru’s contagious intermingling of sound has made his work ripe for a new age of artists sampling his music into new genres and mixing it into DJ sets. “There’s this one, I think it was one of the most played songs I have of my grandfather, it’s called ‘Mukukaranake’,” KMRU recalls, “I heard it being played in a festival context in Nairobi where it was blended with ‘This is America’ (Childish Gambino). There were these two DJs playing, and this is also the track that has been used in the Nike ad. It’s a more up-beat funk type of music. I think it was from his first record.”

Ageni eri na karirui kao (two guests love a different song)

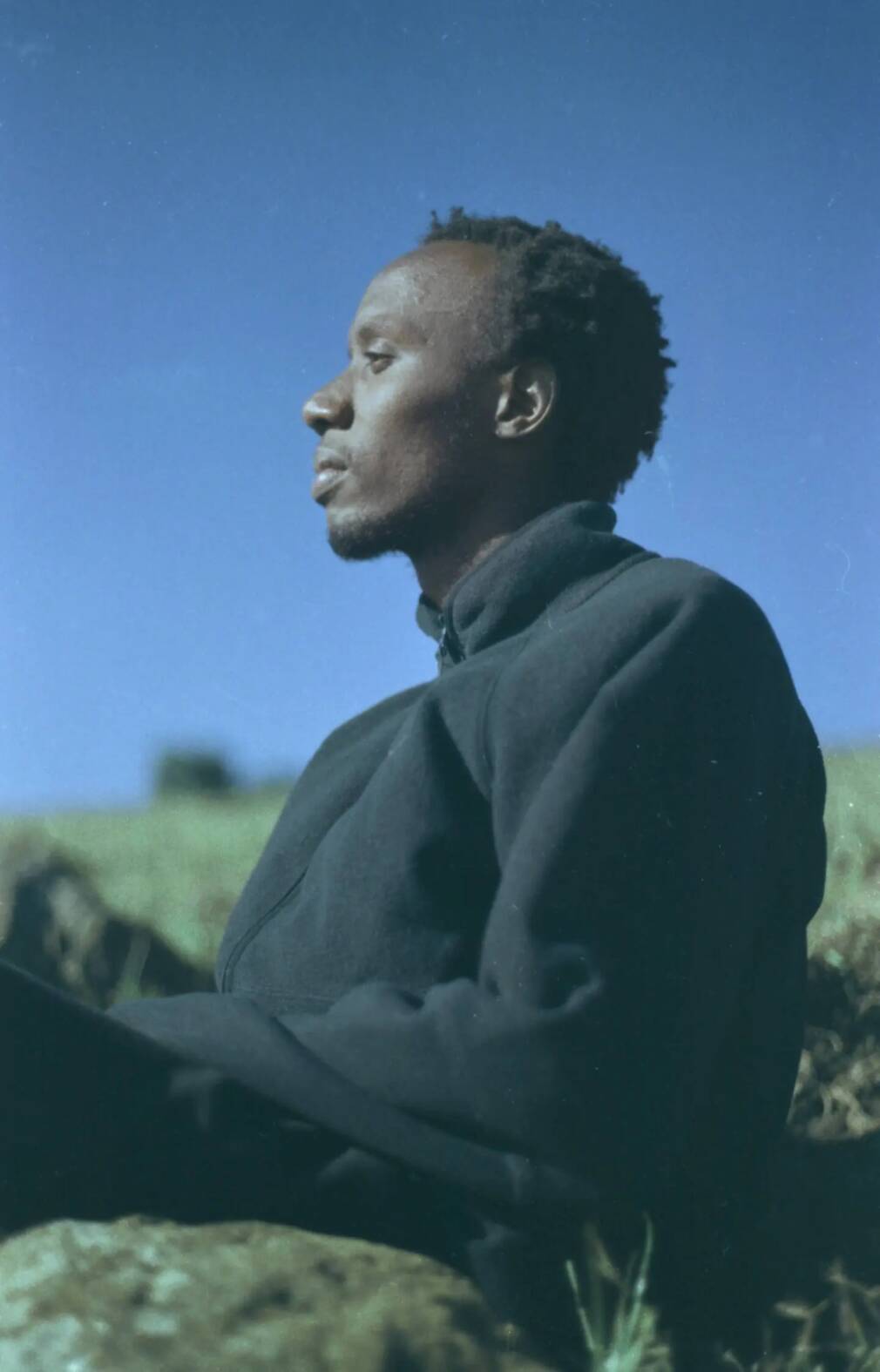

Speaking with KMRU one has a wholly different impression. From behind the screen one finds the portrait of a young artist, contemplative and graceful, kind and touchingly introverted. It’s not the figure you’d imagine haranguing a president in front of thousands of spectators or jumping onto tables during wild jam sessions (as Joseph the senior was known to do in his legendary 1950s Nairobi years).

Instead it seems KMRU has a preference for listening. The young artist’s catalog is a collage of sound samples collected with headphone mics and field recorders, reworked and stretched out into an emotive haze. One of KMRU’s breakthrough earlier works was composed during his trip on the East African Soul Train, an artistic incubator along thousands of miles of train lines. Here, KMRU diverged from his tropical house and techno beginnings, deferring to the musical clamouring of the train itself.

Since, KMRU has been a prolific recorder and producer with little regard for traditional notions of structure or glib ideas of attention span. Dabbling in 12 minute tracks and distorted sound, KMRU’s music now proudly bears the experimental essence of “ambient” and works in the realm of DAWs (Digital Audio Workstations). A stark difference from his grandfather, as KMRU notes, “I think he was a purist in musicianship and he was a tactile musician playing hardware, live guitar and singing.”

While KMRU enjoyed playing guitar with his grandfather, on his debut album OPAQUER, released in 2020, there is almost no identifiable hardware (aside from the piano strung opener) as the soundscapes take shape and evaporate like a passing mist. PEEL and JAR, also both released in 2020, abstract this process even further. For melody, one must fill in the gaps, and any attempt to conjure images is like grabbing on to flowing water (with a few exceptions).

If KMRU is carrying the musical torch for the family, it is a new flint that feeds the fire. “We had a really close relationship.” KMRU explains, “I’m the only grandson that decided to take up music.” Though the way Joseph Kamaru and KMRU express themselves musically is passing through a long stretch of time and technology, preference and demeanour.

Ambient proverbs and brave dissidence

What remains then of Joseph Kamaru by way of his grandson? Both are prolific in their own right. “My father was always asking me, ‘Have you made something new today?’” KMRU says laughing. There is also the project of restoration and re-release KMRU has undertaken (a daunting task considering the mass of music) which one can support through purchases on Bandcamp. Yet there are subtler elements transmitted, shapeless bonds of heritage that work into the keynotes of the Kamaru name.

One is the art of listening. KMRU spoke of a place on his grandfather’s porch where people were welcome to come and wax out their woes. “He had a bench outside his door where people would come and he would just give advice. Not particularly in music but just life advice for people,” KMRU explains, “When we were having conversations you could hear him pausing and letting time for someone else to speak. Or being engaged like an audience or a crowd and letting people speak and listen.”

Another is a reverence for nature, as a source of inspiration, and at times, sound objects to be placed into the music itself. “He always wanted to be in nature. And he also mentioned to me that he wanted to build a studio outside. I didn’t know what he meant. He wanted the ambience of the spaces to be present when he was making music and not like enclosed rooms. I think it wasn’t until recently, with this reissue project, but when I’m listening to his music I realized he was also aware of the surroundings.” KMRU explains, “I don’t know if it was intentional, using bird sounds or aircraft sounds in his piece. There’s one track where he’s traveling to Japan, “Safari Japan” and at the beginning of the track you can hear the plane taking off. The more I became aware of field recording and this practice of sound, I really wanted to ask my grandfather these questions like, ‘Were you really thinking about the sound aspect?’ or, ‘What was your idea of sound in music?’’”

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, is anchoring in authenticity. “He was the most honest person with his work,” KMRU says of his grandfather. “It’s a difficult task for artists to be very vulnerable and put themselves in weird situations. For my grandfather it was a bit extreme because he was telling these stories where he had to hide himself from the government because he was exposing so much stuff that was happening politically that may have even led him to be killed, but he wanted to share what’s happening, mostly after colonization. From the 60’s and 70’s there’s lots of assassinations happening with members of parliament who wanted to take over or were liked by most of the people in Kenya.” For Joseph Kamaru, truth was power.

“I remember when I started making music I was all over the place, maybe trying to find myself,” KMRU explains of his own path. “Before I was making ambient and texture based music, when I was DJing, I wasn’t sure people would relate or understand and in Nairobi people have this energy or urge to dance. I was battling with myself. Do I really want to be playing house music or just express what I’m really enjoying making at home? In 2019 is when I fully decided I’m just going to do this and see how it goes and just be free and not think so much about what people would say, just expressing myself and being honest with what I want to say with my music. It’s not in context with my grandfather exposing so much happening in social contexts but also his music was just very free.”

The fragile totem of legacy

“My grandfather’s work has been so special and also close to heart and I think very fragile.” KMRU explains. “That’s why I started to think about the reissue project which has been ongoing for two years now.”

So far KMRU has released a scattershot of singles in a semi-chronology on Bandcamp and, more recently, a full album, Kimiiri available on all DSPs. It’s not hard to imagine KMRU sitting on the floor with a spread of archives displayed before him, piecing together his grandfather’s work with the delicate care he gives his compositions. There are albums, eras, styles and greatest hits to sift through and compile, to catalog and consume.

“The last conversations I was having with my grandfather was about his music and what would happen after he’s gone. I think he knew, but he was telling me that he made so much effort to see me and there’s this huge bond that we had together and this project was an impetus. After, we were to work on a project together in the studio.”

Unfortunately the studio collaboration never came to pass. Joseph Kamaru passed away on October 3rd, 2018, and his grandson was left to pick up the pieces of his legacy. “One thing my grandfather told me,” KMRU concludes, “was to protect the name Kamaru. It’s important.” KMRU continues to protect the name, bringing it a new dimension and sense of pride far beyond Kenya for both himself and his grandfather.

RIP Joseph, play on Kamaru.

Support KMRU in the Joseph Kamaru reedition project here.