On the eve of independence, highlife was the fashionable music in Ghana. It was the music of high society and of the local elites who gathered for dance parties where people dressed in suits and top hats. As entry to these parties was too expensive for most, those who listened and watched from the outside named it ‘highlife’ – music for those living the high life. It was a mixture of local traditional music with a hint of calypso and jazz – which gave it its edge. And the king of highlife was Emmanuel Teteh Mensah, or E.T. Mensah to his friends.

A saxophonist and trumpeter born in the aftermath of the First World War, he spent his youth playing in great African orchestras. The Second World War made Accra, the capital of Ghana, an important base for the Royal Navy, and British and American military personnel founded orchestras there. Amongst them was the Scottish saxophonist Sergeant Jack Leopard, who recruited E.T. Mensah into his band, The Leopard and his Black and White Spots. For an orchestra that brought together Africans and Europeans, the name was rather apt. E.T. Mensah also had another job as a pharmacist, which helped him to make ends meet as playing the saxophone and highlife music were not yet enough to live by. In the early 1950s he led the Tempos and founded his own club, the Paramount.

It was there that he perfected the sound that would become the sound of independence. His success was enormous and after making a few records in the Decca studios, he left for London. For African musicians, London was the place to be.

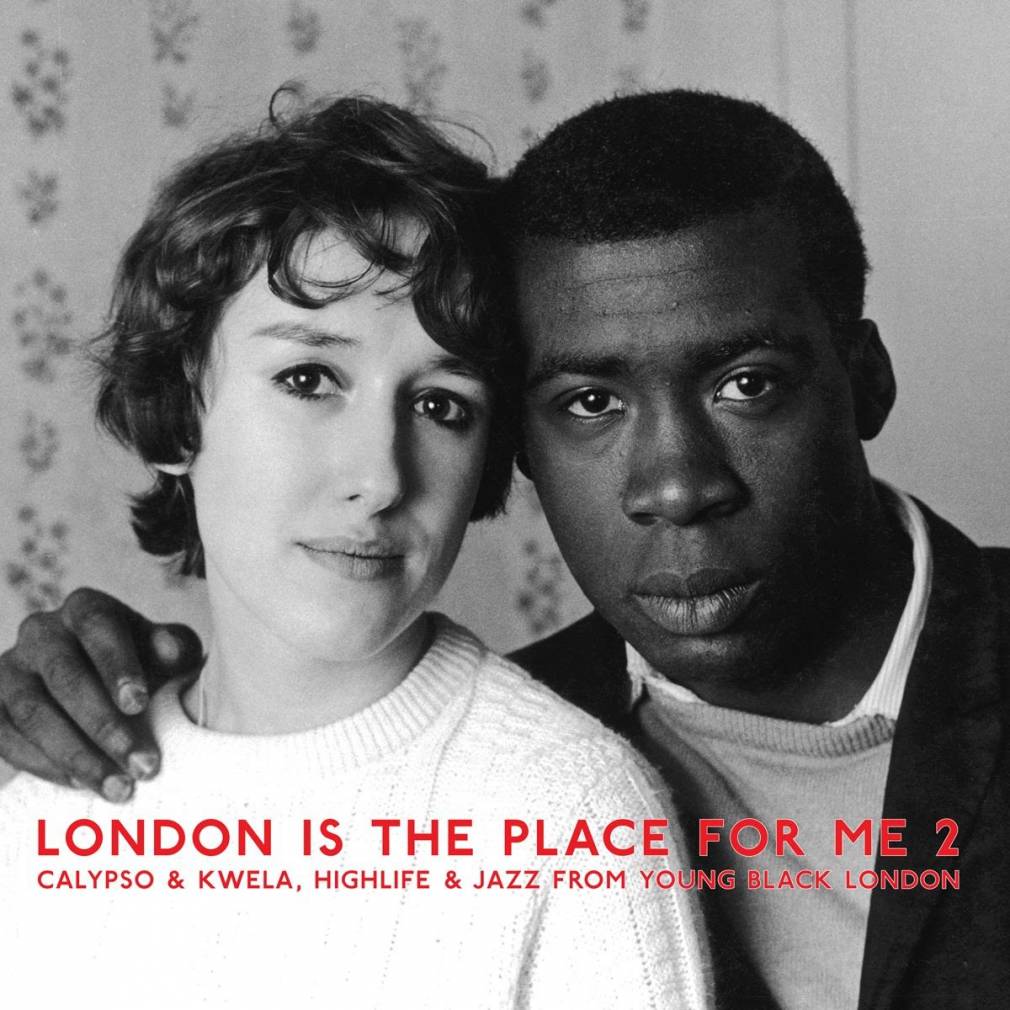

London was a crossroads where people from all over the British Empire met. They came from Africa – Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya, but also from the Caribbean – Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and not forgetting all the African Americans who came through. All these people, students, dockers and artists met in the clubs of Piccadilly. It was there that these cousins, scattered across the ocean by the slave trade, brewed a musical melting pot. It was into this truly pan-African mix that E.T. Mensah happily threw himself. He recorded a few records with Nigerians and Jamaicans from London and met the famous Trinidadian Lord Kitchener.

Kitch, as he was known by his fans, was one of the stars of calypso, a genre born in Trinidad and Tobago, and whose social and political works perfectly reflected the spirit of the age. When E.T. Mensah saw him on stage, Kitch had fallen in love with the latest jazz trend, Be-Bop. Lord Kitchener recorded a calypso tribute to his heroes: Dizzie Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis, each of whom he quotes and imitates in his song ‘Kitch’s Bebop of Calypso’.

Jazz, so popular among these musicians, was a reflection of the Piccadilly clubs. It is the music of cross pollination combining African cultures with those of Europe, producing a variety of fruits depending on the histories of those involved. On the African continent, dozens or orchestras had the word ‘jazz’ in their names: African Jazz, OK Jazz in Congo, Bembeya Jazz and Palm Jazz in Guinea, Mystère Jazz in Mali. Despite finding ‘jazz’ in their name, these orchestras weren’t really playing jazz music, at least not what was heard on records at the time. However, the word ‘jazz’ had become the byword for African and diaspora musicians playing their music with Western instruments, synthesising their own traditions with influences from elsewhere. This is perhaps a broader definition of jazz, be it from the United States, African nations, or elsewhere.

At the same time as this music was infusing black cultures, it was also accompanying a movement of ideas. Pan-Africanism was in full swing – a wave of ideas that posited a common destiny for the world’s black populations, all of whom were living under the yoke of colonial rule or segregation.

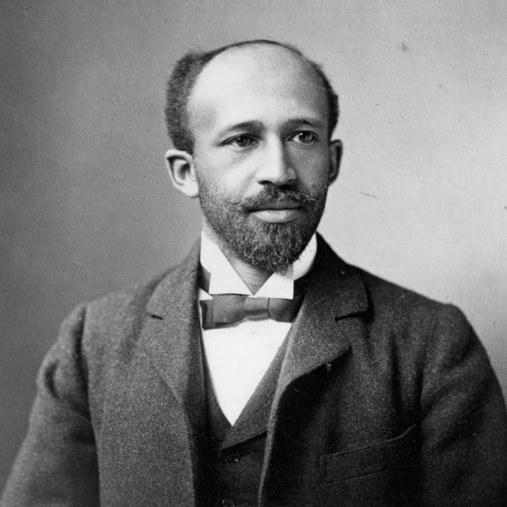

In Manchester, Kwame Nkrumah organised the Pan-African Congress with the African-American du Bois, one of the fathers of Pan-Africanism, and George Padmore, a Jamaican close to the communist party. Although impressed by his ideas, Nkrumah never had the chance to meet Marcus Garvey (about whom the Rastas would sing so much), who advocated the return of black Americans to the African motherland. Garvey founded the Black Star Line, a short-lived shipping company responsible for this transfer.

It is in reference to this Black Star Line that a black star appears on the flag of Ghana. Fed by each of his encounters, Kwame Nkrumah wanted to make his country a home for Africans in the diaspora. As for our king of highlife, E.T. Mensah came back from his London trip full of ideas, more enthusiastic than ever about calypso and jazz. He was ready to become highlife’s pioneer and one of its biggest stars.