On 30 June 1960, the Congo (DRC) became independent. Alan Brain, director of the movie The Rumba Kings, and Manda Tchebwa, historian of Congolese music, have reconstructed in detail, with the help of archives, African Jazz orchestra’s journey. On their way to Belgium, the orchestra was in charge of brightening up the nights of the delegates participating in the negotiations, and composed the ‘Independence Cha Cha’.

The Democratic Republic of The Congo is probably the only country in the world where independence truly has a musical meaning. Beyond the deeds of their politicians, most Congolese associate independence with an all-star orchestra, a continental hit song, and a series of triumphal concerts beyond the homeland. Next to political figures that were key to Congo’s independence such as Patrice Lumumba or Joseph Kasavubu, the Congolese have placed the names of musicians such as Grand Kallé, Docteur Nico, Dechaud, Vicky Longomba, Brazzos, Roger Izeidi and Petit Pierre. All of them are considered as the musical fathers of Congo’s independence.

Those honors are historically justified. In 1960, while more than 150 Congolese politicians were negotiating the country’s independence in Brussels, the African Jazz orchestra performed a series of concerts, in Brussels and other cities of Europe, conquering audiences with the sweet sounds of Congolese rumba. They even managed to compose an iconic song called “Indépendance Cha Cha” that became the soundtrack for independence, not only in Congo but in all Sub-Saharan Africa.

A good way to grasp at the scale of this sui generis circumstance is to imagine a hypothetical scenario where, for example, the United Kingdom became independent in 1965. And, in that parallel reality, the British decide to bring The Beatles to play for the politicians and compose a song about independence. That is how meaningful it was for the Congolese: Congo’s most beloved musical stars accompanied their politicians in the final battle for the country’s independence.

“The politicians won the political negotiations and we, the musicians, showed the Europeans that Congo was already culturally independent and that we had our own cultural identity.”

Petit Pierre

For decades, we knew the basic facts about the trip of the African Jazz orchestra to Europe but we did not know the details. We didn’t know if African Jazz played at the Palais des Congrès in Brussels, where the political negotiations occurred. We didn’t know how many shows they did in Europe. And, most importantly, we didn’t know in what circumstances the song “Indépendance Cha Cha” was composed or interpreted for the first time.

In 2020, together with Congolese historian Manda Tchebwa, we decided to reconstruct, once and for all, the epic European adventure of African Jazz. The information included in photos and newspaper articles told us the story of a musical victory beyond everything the Congolese imagined. The band played more than 60 concerts between Belgium, France and the Netherlands. They performed in some of the most exclusive venues in Belgium and became celebrities gaining fans wherever they went. As Manda Tchebwa said: “The victory of African Jazz in Europe is a light at the end of the long colonial night”.

A cha-cha-cha for independence

Congo’s independence arrived in 1960 after more than seven decades of Belgian rule. In January of that year, dozens of Congolese politicians arrived in Brussels to discuss the terms of the independence of Congo. Those negotiations were known as the “Table Ronde”.

A few days after the Table Ronde started, a strong nostalgia for the homeland and its music had already invaded the Congolese politicians in Brussels. In an unexpected decision that shaped the history of their country, the politicians came up with the idea of bringing a Congolese rumba orchestra to Brussels.

In an interview with François Ryckmans that was published in the book Mémoires noires, Thomas Kanza, one of the organizers of the trip of African Jazz, recalls how it all started:

“The project was that the Congolese who were going to be in Belgium during the winter, could find, in the evening in Brussels, a Congolese atmosphere. It was necessary to give them that chance! That was the idea.”

The brothers Thomas and Philippe Kanza, who were the owners of the Congo newspaper, took over the organization of the whole trip. Thomas asked his brother Philippe, who was in Léopoldville, to recruit the best Congolese rumba band to come to Brussels. Philippe Kanza managed to select the core of African Jazz with some reinforcements from O. K. Jazz. The group that was assembled to go to Europe consisted of: Grand Kallé as director and main singer, Vicky Longomba on vocals, Docteur Nico on solo guitar, Dechaud on rhythm guitar, Brazzos on double bass, Roger Izeidi on maracas and Petit Pierre on percussion. Vicky Longomba and Brazzos were members of the O.K. Jazz orchestra, but they agreed to reinforce African Jazz in this memorable adventure. Since the majority of the musicians were from African Jazz, and since Grand Kallé was the leader and main singer, the band was promoted as a special version of African Jazz.

According to an article published in the Actualités africaines newspaper on January 30, 1960, this special formation of African Jazz, before its departure for Brussels, gave a farewell concert on January 28, 1960, in the Lisala Bar in Léopoldville.

Thanks to another article published in the newspaper Présence congolaise, we know that Philippe Kanza accompanied the ensemble to Maya Maya airport across the Congo river in Brazzaville. On January 29, 1960, they took a flight to Brussels, via Paris. Grand Kallé explained the reasons for this trip in an interview he gave to Actualités africaines:

“We are going there to play, on February first, at the Ball of the Table Ronde. This February first coincides with the anniversary of the newspaper Congo. And it is at the expense of the African Advertising Agency that we are making this trip to Europe.”

The African Advertising Agency was a sort of modern marketing and public relations agency. They financed the trip, handled the contracts of the band, and found opportunities of sponsorship. Grand Kallé confirms this in an interview published by Actualités africaines on February 20, 1960:

“The African Advertising Agency had promised us a trip to Europe without this ever happening. But, suddenly, its representative in Léopoldville came to find me a week before our departure to tell me that everything was ready for the trip. We could say that The African Advertising Agency is our manager.”

African Jazz arrived in Brussels, via Paris, on January 30, 1960. Taking into account that the Table Ronde started ten days before, on January 20, it’s evident that African Jazz did not play at the opening of the Table Ronde. Furthermore, the band did not stay at the fancy Hotel Plaza, where the Congolese politicians were staying, but rather at a modest family pension located at 52 Rue de l’Association in Brussels.

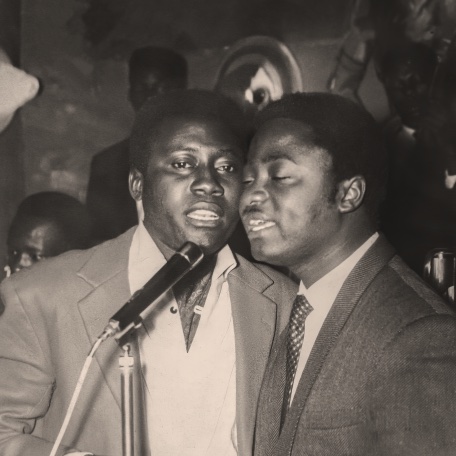

The first official performance of African Jazz in Brussels happened on February 1 in the Hotel Plaza, located in the center of Brussels. A long article published in Actualités africaines provides all the details about that extraordinary night. The soirée was promoted as “Le Bal Congo” or “Le Bal de l’indépendance”, and it was an exclusive gala organized by the Congo newspaper to celebrate the just attained Congolese independence. The place was brimming with Belgian and Congolese politicians, African students, ambassadors and football players, Belgian authorities, and Africans living in Brussels. Many Congolese had traveled from different places in Belgium to see African Jazz. The Flemish public TV broadcaster even sent a crew to film the event.

Around 10 p.m., on that night of February 1, 1960, Philippe Kanza delivered a speech about the obstacles that Congo faced in the struggle for independence. His brother Thomas reminded the guests why “Le Bal de l’Indépendance” was organized and then introduced, one by one, the African Jazz musicians. He ended with a passionate: “Kallé, Chauffez Bruxelles!”.

Immediately after the battle cry of Kanza, Grand Kallé and African Jazz launched into their new song “Indépendance Cha Cha”. A few seconds later, the dance floor was jam-packed. Africans and Europeans were dancing together to the captivating beat of Congolese rumba. Patrice Lumumba, Joseph Kasavubu and the other politicians from the Congolese delegation were happy to hear their names mentioned in the song. African Jazz continued grooving to an enthusiastic crowd until 5 a.m. the next morning.

For the members of African Jazz, it was hard to believe that a Belgian TV crew was filming their performance and that many European journalists were trying to interview them. After decades of Belgian colonization, that experience was a historic victory for Congolese culture: the night when African Jazz had conquered Belgium with music.

The best sources of information we have about the creation of the song “Indépendance Cha Cha” are the memories of Thomas Kanza and the musicians. All of them remember that the night before that first show in Europe, the night of January 31, Thomas Kanza went to the family pension where the group was staying. He asked Grand Kallé to compose a song for the country’s independence and handed him a paper with the names of the Congolese politicians participating in the Table Ronde. Under the direction of Grand Kallé and with the help of Thomas Kanza, the band worked almost until the next morning to finish the legendary song.

When Congolese rumba invaded Belgium

African Jazz spent three months in Europe with a busy schedule. Every Tuesday and Friday, from 8 p.m. to 2 a.m., the ensemble provided live music for the Congolese politicians in the dancing bar of the Hotel Plaza. This was one of the main reasons for the band to be in Brussels, and it is a strong testament about the essential role of dance and music in Congolese society.

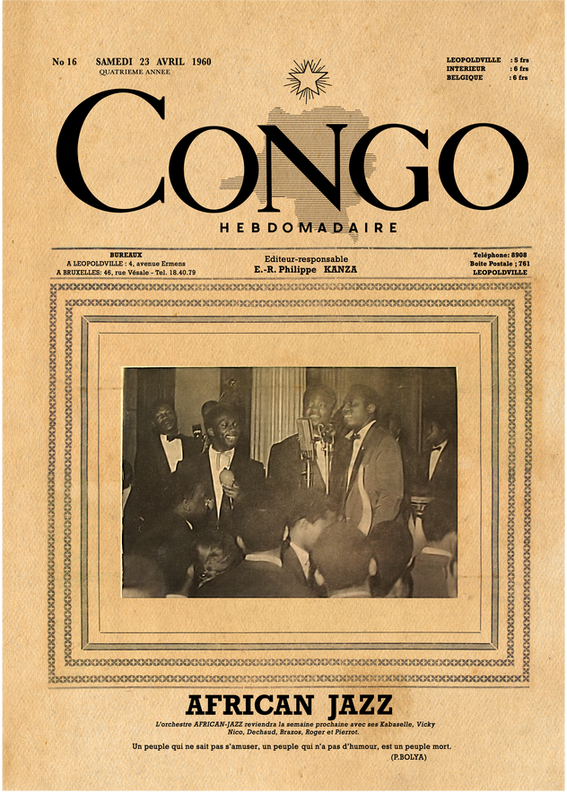

“A nation that does not know how to have fun, a nation that does not have humor, is a dead nation.”

Paul Bolya (Congolese politician)

Every Wednesday and Sunday, from 8 p.m. to 2 a.m., African Jazz turned up the heat at the small but charming café Le Dauphin Royal, located at Rue Royale in the commune of Schaerbeek in Brussels. Throngs of Congolese crammed the café for every show. Le Dauphin Royal was the place where African Jazz felt more at home. So much so, that one night, Grand Kallé and Docteur Nico played a traditional Congolese song for a fan who had just become the father of twins.

In less than a week, the Congolese orchestra had become popular in Brussels and some prominent brands had started to notice. The famous department store Grands Magasins de la Bourse, located in front of the Brussels Stock Exchange building in the Boulevard Anspach, hired African Jazz to create a nice mood in its store. Every day with the exception of Sundays, from 2 p.m. until 6 p.m., they would entertain the clientele of Grands Magasins de la Bourse. In an interview with the Actualités africaines newspaper, Grand Kallé described one of those gigs:

“We played at La Bourse in front of 1,300 young students. You had to see how they applauded us. We were supposed to play only from 5 to 8 p.m., but they didn’t want to let us go until 10:30 p.m.”

The African Jazz shows in Europe were not limited to commercial campaigns, hotels and small bars. The ensemble brought Congolese rumba to the famous Au Midi Dansant, a dancing hall where most of the great European orchestras were featured regularly. The music of African Jazz was such a revelation for the spectators that the band was invited to play for a second time.

Around the last week of February, African Jazz was invited to participate in a music festival called “La Nuit de St Vincent”. The concert headliners were some of the most famous Belgian music acts, among them the singer Annie Cordy. Grand Kallé told a reporter from Actualités africaines that all those artists were pleasantly surprised with the music of the Congolese ensemble.

On February 27, African Jazz gifted its European followers with another outstanding performance in the Casino de Chaudfontaine in Liège. They were hired by the administration of the Belgian soccer team Royal Standard de Liège to enliven their annual celebration called “Le Grand Bal du Standard”. Initially, the famous orchestra of Vicky Down was going to be the only musical attraction of the event. But, after listening to the vibrant rhythms of African Jazz, the organizers decided to include them in the soirée. African Jazz created such a buzz in Belgium that once the soccer team announced that the Congolese were going to play in Liège, all the tickets for the gala were sold in a few days.

The soirée started with Vicky Down warming up the venue with its usual repertoire of boleros, tangos and other international music styles. At midnight, African Jazz took the stage. Some people in the audience – composed of soccer players, businessmen, celebrities, and friends of the team – were wondering if the Congolese could play at the same level as the Vicky Down orchestra.

Docteur Nico, maybe responding to the attendees’ doubts, broke the ice playing some guitar improvisations. Then, Grand Kallé commanded the band into an explosive cha-cha-cha groove and started improvising over the music. Knowing that he needed to win the hearts of the listeners, Grand Kallé started singing the victories of the soccer team, as well as the names of the soccer players. The crowd went wild. Nobody expected such a gesture. Suddenly, a sort of dancing fever descended over the ballroom. There was not even space to do the cha-cha-cha steps properly.

As the night went on, the heat only went up. Vicky Down, who was watching from the sidelines, confessed to a journalist that he had never seen a concert with such lively ambience before. The seductive sound waves of Congolese rumba did not stop until 5 a.m. when the organizers were forced to close the casino.

African Jazz did many more shows in Belgium: they played at the bar Les Anges Noirs, at a dancing bar called Eden, and at the Castle of Beaulieu, most likely the one located in Machelen. They also initiated Dutch audiences in the mesmerizing pulse of Congolese rumba during a concert in the city of Hilversum in the Netherlands. But, none of that equaled what happened in France. An association of foreign students in french universities called La Fondation d’Outre-Mer hired the ensemble to play for two nights in Paris. According to what Grand Kallé and Vicky Longomba mentioned in an interview published in Actualités Africaines on 9 May 1960, the enjoyment and dancing skills of the concertgoers made these concerts truly special for the band.

“African Jazz Mokili Mobimba”

(“African Jazz is everywhere”)

Grand Kallé: “Not only did we have the greatest success of our career there, but we also met the best dancers in the world. At the first ball, most of the audience barely knew how to do the steps of a rumba. Go see them now, they dance it with an elegance and a perfection that Maître Taureau himself would be jealous of.”

Vicky Longomba: “The first ball for the Table Ronde in Brussels really impressed me. But it is indisputable that the two balls in Paris will always remain engraved in my memory.”

Soon enough and without planning it, African Jazz acquired a passionate group of fans that waited for them at every venue. Petit Pierre recalls that some of them even rented buses to follow the orchestra around.

Somehow, each member of the band had become a celebrity. Petit Pierre impressed everybody with his talent and youth. He was barely eighteen years old. Brazzos impeccably commanded the rhythm section from the double bass. Although It seemed that he had played that instrument for half a life, Brazzos never played it until he arrived in Brussels. On arrival in Brussels, the African Jazz musicians realized that they had two rhythm players, Dechaud and Brazzos, but no double bass player. Brazzos, who had witnessed the breathtaking guitar synergy between the brothers Nicolas Kabamba wa Kasanda (Docteur Nico) and Charles Mwamba wa Kabamba (Dechaud), decided to step away from the rhythm guitar and take over the double bass. He learned to play it in less than three days. Roger Izeidi was a sensation shaking his maracas with contagious energy while he taught the audience how to do the cha-cha-cha. Vicky Longomba conquered the listeners with his velvety and elegant tenor voice. Grand Kallé enchanted everyone with his high-pitched voice, his passion, his magnetic personality and his exquisite sense of rhythm.

But the musician who really stole the show and left the European concertgoers speechless was Docteur Nico. Each time that Nico’s fingers elicited a note from its guitar, the listeners would start wondering where the piano player was. Only to realize in awe, seconds later, that those catchy melodies were coming out of Docteur Nico’s guitar. They simply could not believe it. The nickname “Docteur” was given to Nico Kasanda during a radio interview. The radio host told Nico that he was so skilled with the guitar that he seemed like a doctor executing a complicated operation.

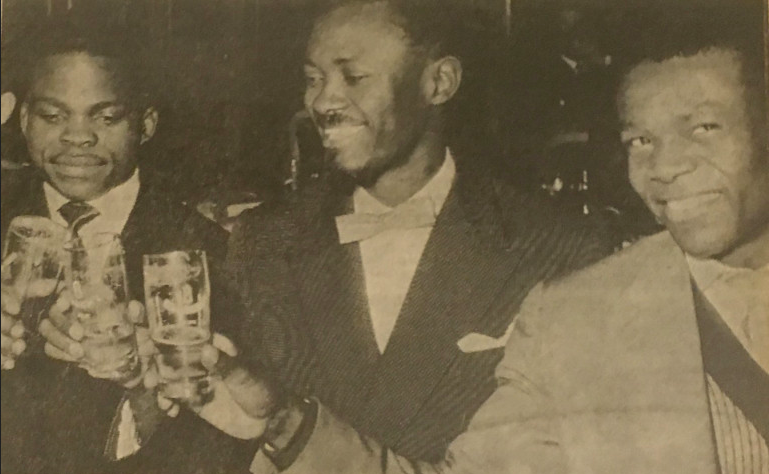

The financial role of the African Advertising Agency in the spectacular sojourn of African Jazz in Europe is corroborated by a couple of publicity stunts in the schedule of the artists. The whole band visited the famous Martini Club in Brussels and posed for the press. They also visited the macaroni factory of Soubry and had lunch with the owners of the company.

It is important to mention that there is no evidence to support the idea that African Jazz played in the Palais des Congrès in Brussels, where the Table Ronde was held. As much as this is a common belief among musicians and Congolese rumba aficionados, it seems to be a confusion born out of the gentle erosion that time creates in our memories, even the most cherished ones.

The unexpected 3-month European tour was long for the musicians – who missed their homeland – but it was too short to reap the musical victories. African Jazz had received invitations to perform in Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union, but there was no time left to keep touring.

Before ending its European tour, African Jazz performed in two more special galas at the Hotel Plaza. On April 22, 1960, they played at “Le Bal de la Table Ronde” celebrating the end of the political negotiations. One week later, on April 27, the orchestra played its last show in Europe, a farewell to their most loyal fans. This gala was promoted as “Le Bal de Journal Congo” or “Bal d’Adieu de l’African Jazz”.

Grand Kallé: “Everywhere, people believed that we came from the Congo but not that we were capable of making such impressive music. We have confirmed to other nations, to some extent, that the Congo is ready to enjoy its independence.”

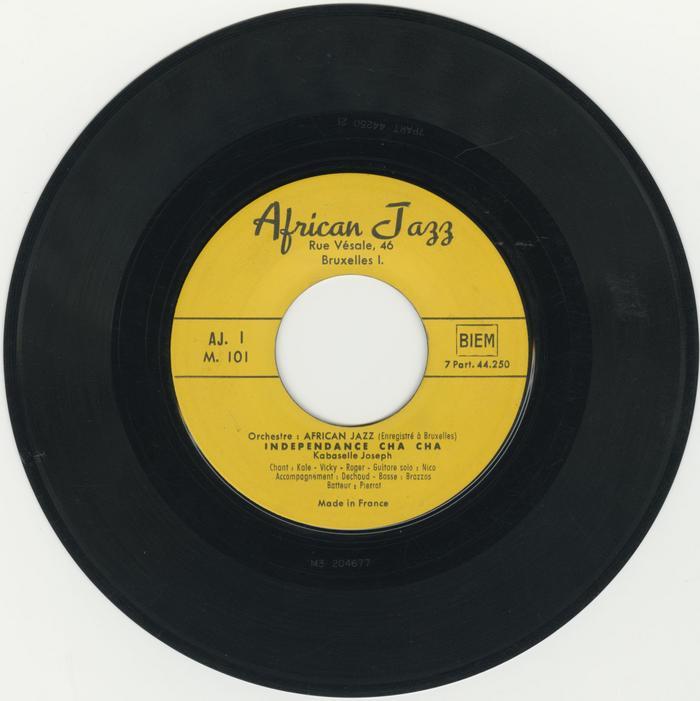

A couple of weeks before the departure of African Jazz from Europe, the band managed to record “Indépendance Cha Cha” in a studio. They hired a French company to print hundreds of 45 rpm copies and sent them to Léopoldville. Grand Kallé wanted his fellow compatriots back in Congo to listen, as soon as possible, to the song that carried the good news about independence. The records arrived in Léopoldville and were distributed to several record stores and radio stations. Jean Lema, who was a radio host and supervisor in Radio Congo Belge, received the records and made sure that the song was played before the start of every radio show.

When African Jazz arrived back in Congo, a multitude of enthusiastic fans welcomed them with hurrays in the Léopoldville airport. If the politicians brought the independence back to Congo in their suitcases, African Jazz had magically turned independence into a joyful song that everybody could dance to and sing.

The new nation had its own musical heroes.

You can find the complete printed version of this text and its images in the booklet of the album “Joseph Kabasele and the Creation of Surboum African Jazz 1960-1963” (Planet Ilunga label) released on 30 June 2021.