Thirty-one years ago, Nelson Mandela walked out of the Victor Verster prison, where he had spent the last years of his detention, finally appearing before the eyes of the world. He was free, at last. Fortunately, from the mid-1980s, he and his closest companions had been moved from the Robben Island penitentiary to less harsher places of detention, where discussions with the South African authorities could take place discreetly.

International mobilization set to music

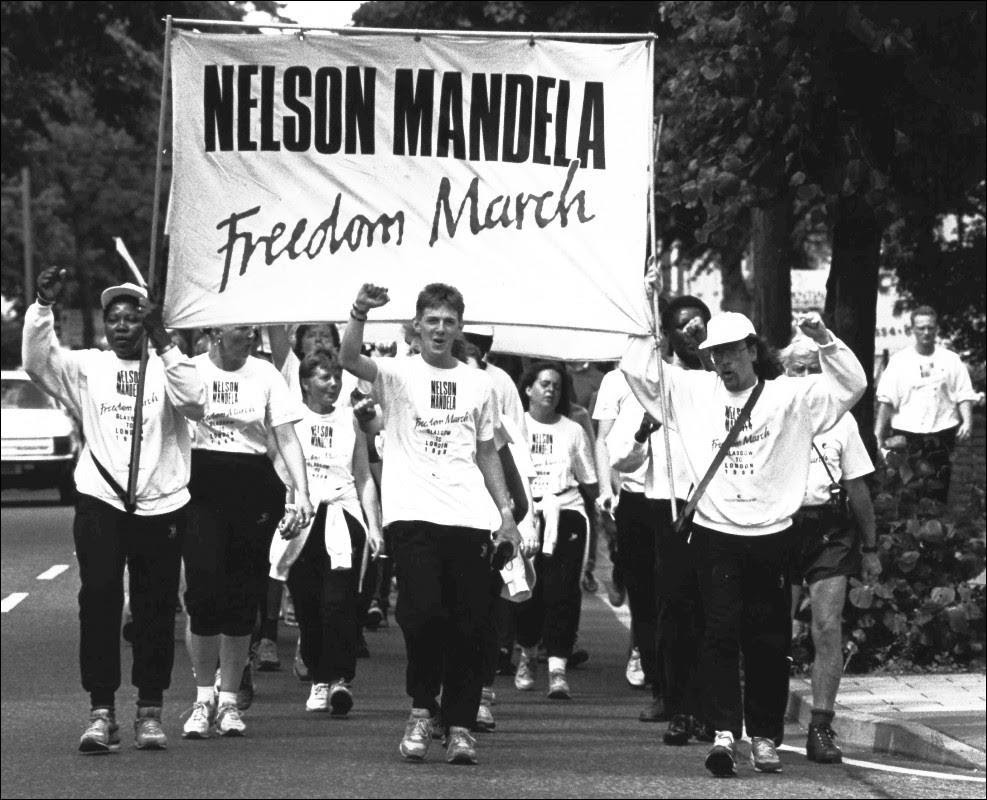

At the same time, the various actions of anti-apartheid organizations, beginning with the then illegal ANC, made the townships ungovernable. International pressure, in the form of a growing boycott, was pushing the government of Pieter Botha into a corner. The standing of South African authorities became increasingly less viable, as the mobilization of both civil societal organizations and artists created an overwhelming voice in support of the anti-apartheid cause.

In 1984, the British band The Specials recorded the track “Nelson Mandela”, which became one of the definitive anthems that united those outside of the country to call for the activist’s release. A year later, Youssou N’Dour also recorded a song dedicated to the leader whose portrait was banned in South Africa. This detail helps us to understand the title of Johnny Clegg’s famous song, “Asimbonanga” (“We haven’t seen him”), released in 1987 and immediately topping the European charts. Undoubtedly, the huge concert organized on June 11, 1988 at Wembley Stadium, in the run-up to “Madiba”’s seventieth birthday, formed the peak of this international mobilization.

It was at the occasion of the eleven-hour long concert, broadcast on TV worldwide and watched by no less than 600 million people around the world, that the band Simple Minds composed “Mandela Day”, performed that day for the first time in front of an audience (officially recorded the following year). In addition to Sting, Harry Belafonte, Tracy Chapman, Dire Straits and Joe Cocker, the lineup featured the Mahotella Queens, Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela (who the year before recorded “Bring Him Back Home”).

Although one concert alone might not have made much of a difference, it represented the height of an international campaign that the world could no longer ignore. In 1988, it was almost impossible to not know the name, “Nelson Mandela”.

In South Africa, the noose is loosened

The following year, Brenda Fassie drove the point home with “Black President”, a song that was so pertinent that it was immediately censored by the authorities, who had already lost the battle of storytelling and PR spin by then anyway. That same year in July, 1989, State President Pieter “P. W.” Botha fell victim to a stroke and was replaced by Frederik “F.W.” de Klerk who decided to free Mandela’s old comrades in arms (such as Walter Sisulu) and then to legalize the ANC once again. It is February the 2nd, 1990, and the same man who came to share the Nobel Peace Prize with Mandela announced the release of Mandela in Parliament. The newly-freed man had become so important that his actual release had to be postponed for a few days as a security measure.

On February 11, it was a done deal: Nelson Mandela stood in front of TV cameras for the whole world and to the eyes of a nation that knew, despite the difficulties, that the days of apartheid were numbered. It then became evident that 27 years of detention had not blunted the determination of Madiba, who made his first public speech in front of the Cape Town City Hall:

“I stand here before you not as a prophet, but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands. […] Today the majority of South Africans, black and white, recognize that apartheid has no future. It has to be ended by our own decisive mass actions in order to build peace and security. […] The factors which necessitated the armed struggle still exist today. We have no option but to continue.”

How the story continues is well-known, and despite the difficulties (notably the violence of white supremacist groups, or the civil clashes in townships between members of the ANC and of the Inkatha Freedom Party, which the government attempted to exploit), the last laws of apartheid fell one by one. A new constitution was announced, and Mandela ended up where Brenda Fassie had foreseen him: as the first Black president of a truly democratic South Africa.

The musical tributes, which began pouring in while he was still locked up, have not stopped raining down since: from Cameroon’s Petit Pays to Jamaica’s Burning Spear, from the Congolese Theo Blaise Kounkou to Tabu Ley via King Kester Emeneya, without forgetting the Reunionese Danyèl Waro and Christine Salem or the Trinidadian Mighty Sparrow, Archie Shepp and Abdullah Ibrahim, and even, following the hero’s death in 2013, the French pop singer Francis Cabrel. All of them can be found in our playlist: in all of their tones and variations, they accompany a thought that Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela liked to share: “Politics can be strengthened by music, but music has a potency that defies politics.”

Listen to the Nelson Mandela playlist on Spotify and Deezer.