Nourished by jazz classics and West African music, the young Ibaaku Bassene made his first steps as an artist in the world of 90’s hip-hop under the Staz moniker. At the beginning of the 2000s, he left to live in Bamako for a year, where he threw himself wholeheartedly into music, juggling between live radio freestyle sessions, setting up a band and taking part in the first Malirap mixtape. Upon his return to Dakar, he joined the Lyrikal Zone 3 collective, a sort of West African Wu-Tang: a crew of fifteen guys who set stages across the region on fire.

But the curiosity and thirst for innovation of this tireless explorer led him to discover other worlds, both sonic and visual. First, through the I-Science band, quickly known as a musical UFO on the Senegalese scene. He also joined the Petites Pierres collective, where he rubbed shoulders with other creatives such as the stylist Selly Raby Kane, with whom he produced the soundtrack of the Alien Cartoon collection, during the 2014 Dak’Art Biennale. This was a foundational moment during which Staz became known as Ibaaku, a sonic poet whose futuristic universe is defined by the fusion of influences as diverse as possible. This mutation brought him international acclaim and visibility, with tours and the release of his first solo album in 2016, on the Akwaaba label. Since then, he’s been alternating big stages like Rennes’ Transmusicales or the Bushfire, with more underground projects like the Waï Faï Spirit band.

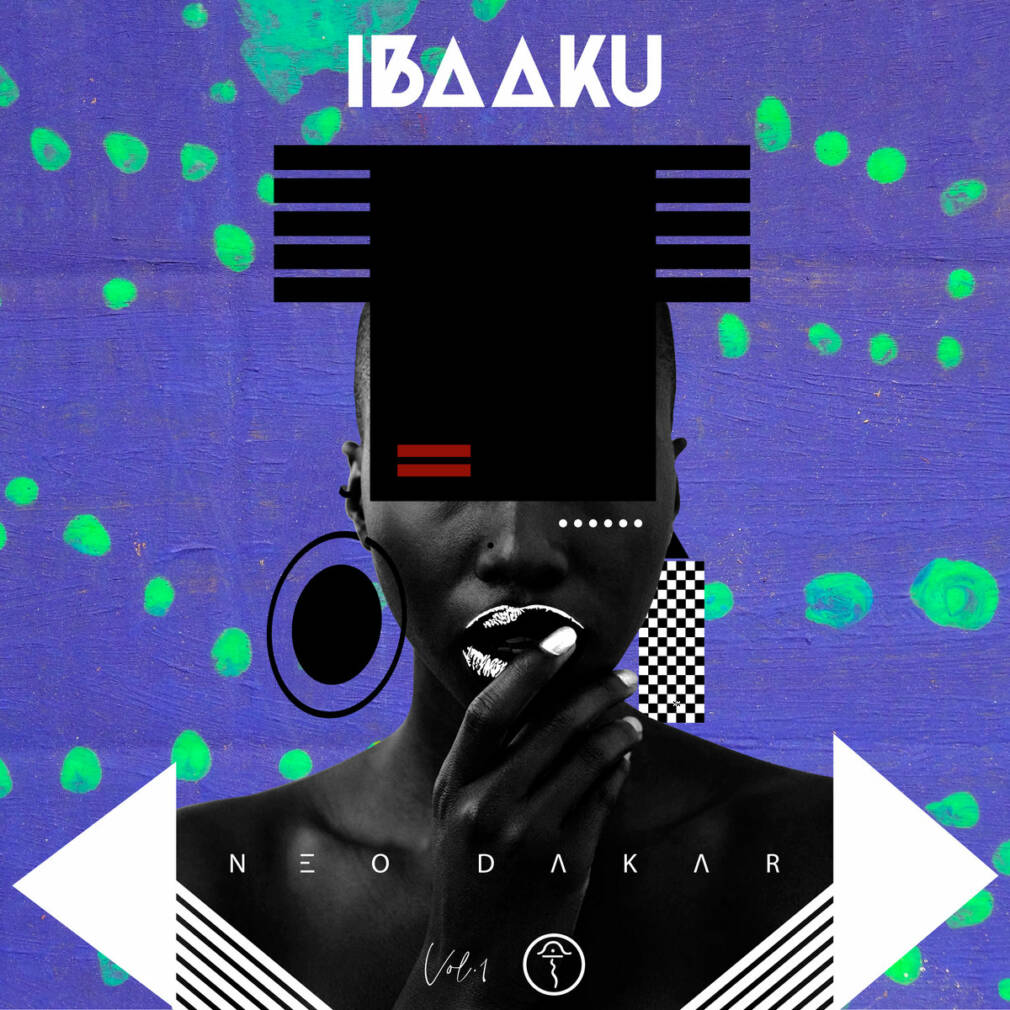

His music draws bridges between past, present and future, and encourages his audience, whom he affectionately calls “my hybrids”, to explore worlds of diversity. His latest project, Neo Dakar, pays homage to the actors of the new dakarois artistic scene and is a witness to the profound changes that the city is undergoing. Come meet Ibaaku, pioneer of the Senegalese electro scene.

First of all, can you tell us about the musicians who influenced you?

Basically, I grew up listening to a ton of African music and jazz, taken from my father’s huge vinyl discotheque. He had deep Afro-American music crates, like Duke Ellington, Quincy Jones, Miles Davis and of course all the West African classics with Youssou Ndour, Salif Keita, Waziz Diop, Xalam, Meiway and many more… well, the list is almost endless. I loved the music, of course, but beyond that, I devoured books about the musicians themselves. I wanted to understand their state of mind, their lifestyle, their way of working.

Later on, like most kids my generation, I fell deep into hip-hop, and was particularly drawn to RZA from Wu Tang. I was also doing martial arts at the time and that helped me penetrate his universe. Of course, there are many other cats whom I liked and influenced me, like J-Dilla, Timbaland, and Swizz Beatz in particular. That’s how I discovered the funk and soul samples and the mix of musical and cinematographic cultures.

In the end, what did you learn from these readings?

I’ve always been interested in the story behind the curtains, you know, beyond the music itself. Understanding characters and life trajectories. Miles Davis’s bio, for example, is super powerful: the rebellious side, the intensity of his music, his words, his life choices.

The truth is that being an artist is much more than a career. It’s a whole path, a whole learning process, filled with experiences and encounters that shape one’s way of life. I always had this model in mind: the jazzman who plays until his last breath, who releases timeless albums, who renews himself, crosses eras, and remains edgy and current, while bringing something fresh and new. There is also this idea of staying up to date, even technologically, like when synthesizers arrived, it triggered a whole psychedelic wave in jazz, it also allowed us to explore new fusions, with rock for example. In this sense, the album Back On The Block by Quincy Jones is one of those that have marked me the most. It’s crazy, you have jazz legends like Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan with rappers like Ice T and Big Daddy Kane on the same record. It’s so beautiful, and shows that in music, there are really no limits!

Breaking the boundaries between genres, drawing on the most diverse influences… I don’t know if there’s a connection but is that why you use the term “hybrid” in all sorts of ways?

(Laughs). It’s true, it’s a term that I use in almost everything I do… In fact, this idea of “hybrid” really represents how I grew up and the diverse influences I received. It’s a way to speak to an audience that is similar to me, with a background that is not stuck in one culture. It evokes people who dig deep, who have gone to find very different inspirations to shape their views. I have been lucky enough to be confronted with many different lifestyles. Moreover, in the universe of Alien Cartoon, Ibaaku has an Alien mother and a Human father: that makes him a hybrid.

There is wealth in diversity, although these days, not everyone seems to think so. This is something that has always frustrated me in Senegalese hip-hop: there was always this debate about what is real hip-hop and what isn’t. It’s just so sterile, and really, if you know the history of hip-hop, you can’t even have that kind of debate. I mean we are talking about a movement that has drawn from so many different sources and origins. Music is a continuum and it’s in constant evolution. For me, it’s beautiful to see different worlds merging, giving something new, providing an alternative. I realize that many people find themselves in such a vision.

Your latest project is called Neo Dakar, what is it about?

I think of Neo Dakar – or the New Dakar – as a cultural and artistic movement, which covers architecture, music, design, cinema, literature, dance, etc. For each discipline, there are different artists who make things happen. At the beginning, the movement was alternative, on the margins, but its popularity is now on the rise, with Selly Raby Kane (stylist, designer), Alibeta (musician), Omar Victor Diop (photographer), Sahad (musician), and the dance company La Mer Noire. There is also the writer Felwine Sarr and a new literary wave… many new profiles are emerging in Dakar, while also reaching an international audience. In parallel, there is also what we can observe every day: the city itself is changing – not necessarily in the right direction – but it is a fact, all this construction, all this effervescence. It’s mutating and evolving. It’s this whole phenomenon that I call Neo Dakar.

I got there by projecting myself into the future and putting myself in the shoes of an art historian, wondering what I would call this period. The name came from this exercise. I had a show on Vibe Radio whose ambition was to give a platform to new artists. Especially with the advent of electronic music in Senegal, with Guiss Guiss Bou Bess, ElectrAfrique, and others… The scene is bubbling with energy, electronic music events are growing, club DJs are starting to play sounds like amapiano and afro house regularly… Ten years ago, there was nowhere you could hear this kind of music in Dakar.

Musically, Neo Dakar is also my way of connecting with the Senegalese audience and to put Dakar on the world map of electronic music. I see this project as playing a kind of ambassador role for innovations that take place at home, and that the world doesn’t necessarily get to hear about. Last year I launched Neo Dakar Vol. 1, which I see as the manifesto of Dakar’s creative scene as it moves into the future. Volume 2 of the series has just been released, in a similar aesthetic.

Although oriented towards novelty, Neo Dakar starts by going back in time, revisiting classics like Coumba Gawlo or Youssou Ndour. Can you tell us more?

In terms of aesthetics and inspiration, I am a big fan of vaporwave (see artists like ONeohtrix Point Never or Macintosh Plus). These producers have been drawing from the past of capitalist and technological culture. There is a nostalgic side of the 80s/90s which is in fact very current. This approach speaks to me a lot, and I tried to affirm it more in my musical production. There is also a more conceptual dimension, the idea of not running too fast towards the future. You have to draw from the past, from your heritage. You have to understand where you come from in order to know where you are going. Finally, a third element is the big emotional charge that I feel in relation to these pieces and these artists, who shaped our universe.

I think we are living in a time of transition. We are in the future that thinkers and artists have always prophesied. With the economic, social and health crisis and the digital revolution, our generation is living in a pivotal period that simultaNeously brings us back to history and projects us towards the future. But what’s next? As artists, we must take a stand on these questions, because culture has always had this capacity to anticipate things.

For Neo Dakar Vol. 1 and 2, I wanted to draw from classic tracks that many Senegalese people will identify with immediately. You see, an album like Wommat (editor’s note: by Youssou Ndour), from which I sampled the song “Dem”. Unless I’m mistaken, it was Senegal’s first gold record, thanks to the worldwide hit “Seven Seconds”. For us, it was the first album that mixed mbalax, hip-hop and soul for example. In Neo Dakar, I reinterpret this kind of fusion.

The series will continue, this time with a more futuristic tone. In fact, the first two volumes contain a lot of sounds that I have produced a long time ago. Some of them even ten years ago. At the time, I felt that they didn’t really fit with the state of the scene in Senegal. Maybe it was too experimental or avant-garde. I was waiting for the right moment… Now that it’s out, I can turn the page and look to the future. Volume 3 is due out before the summer, with more vocals on the beats, because yes, I love to sing (big smile).

Find Ibaaku in our playlist afro + club playlist on Spotify and Deezer.

Neo Dakar Vol. 1 et 2, out now via Bandcamp.