With the superb reissue of Nigerian Orlando Julius & Ashiko afro-funk album Love Peace & Happiness, the French label Hot Casa, run with passion by the pair Julien Lebrun & Djamel Hammadi celebrates its 49th release in 14 years. If the catalog mainly offers 1970s afro funk reissues – with beautiful artwork, rich booklets with interviews and socio-historical texts – it also welcomes today’s productions of artists who pick up the funk torch. The latest example is Vaudou Game’s punchy vintage funk and their irresistible album Kidayu, dancing between Togo and France.

A few months before Hot Casa’s 15 years celebration, Pan African Music talked to one of the label’s two founder, Julien Lebrun.

Listen to Hot Casa Records playlist

Listen to Hot Casa Records playlist

PAM: June will see the 50th release for Hot Casa in the course of 14 years of activity. Would you say the label eventually found its audience?

Julien Lebrun: I’d say yes, and mainly thanks to the apparition of the afro-tropical and afro-soul DJ scene at the beginning of the 2000s all over the world. This new scene gathered scenes that used to be divided between hip-hop, funk, soul and house.

This very scene seems to be Hot Casa’s trademark, but why is electronic music not part of the catalogue yet?

I guess it’s a matter of generation gap. Young people in their 20s or 30s have a very different clubbing culture than us. Take Mawimbi, for example: they are labelled “tropical” or “afro”, too, but they generally start their set with heavy danceable 125-bpm edits. This is what their audience wants, when dancing in a club from midnight to 3 am. We, as well as our friends Nickodemus or iZem, we like to start smoothly at 10 pm, and slowly raise the pressure, maybe because we’re older! [laughs] And our audience is different than theirs.

Hot Casa is you, Julien Lebrun, and Djamel Hammadi aka DJ Afrobrazilero. Do you equally share the tasks, like a modern couple?

We met in 1997 while working on the radio. We get along very well musically speaking. Djamel is more often in the field than me, because record digging is a daily job for him, whereas I only travel twice or three times a year, and I generally choose different destinations than his. As far as the rest of the tasks are concerned – seven or eight records a year – we share 50/50 : digging, licensing, administrative process, mastering, pressing…

HOT CASA WAS BORN OUT OF THE WILL TO MAKE AVAILABLE SOME UNKNOWN, FORGOTTEN OR DISAPPEARED ALBUMS. WE FOCUS ON QUALITY MUSIC, INTERESTING STORIES TO TELL, RICH SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXTS AND GOOD ARTWORKS.

What came first? Digging forgotten ’70s vinyls or founding a label?

Hot Casa was born out of the will to bring some records back to life and make them available again: unknown, forgotten or disappeared albums, with very limited pressed copies – generally for economic reasons at the time. We focus on quality music, interesting stories to tell, rich socio-cultural contexts and good artworks. But from the beginning, we’ve also wanted to promote contemporanean artists. Vaudou Game is an interesting example because I feel that this band is the musical link between past and present, between our reissues and our current productions: they have both the analog vintage sound, and the modernity of the melodies that appeal to a large audience. The successful radio hit “Pas Contente” proves it pretty well.

Is it still possible to be a digger today? Are there any records left to be discovered in a time when so many Western DJs are digging together?

Productions were limited at the time (1960s and 1970s), there are less and less stock and the few copies left are not in good condition. It’s almost impossible to find anything good in Senegal, Mali, Burkina, Benin or Togo. You can be lucky, obviously and be able to rummage through a deceased person’s collection, or meet someone who wants to get rid of their records. You may also find an amazing record in the midst of tons of uninteresting boxes of vinyls.

AND THERE IS SOMETHING WE SHOULD NEVER FORGET: A DIGGER ONLY FINDS A RECORD, BUT HE’S NOT THE ONE WHO CREATED THE MUSIC. LET’S REMAIN MODEST.

How many records do you own?

A few thousand. But I won’t give the exact number, because I value quality over quantity. And I’m not entering any competition with other vinyl diggers, who often like to boast about their large record collection. I even got rid of many records recently, because I like to be able to listen to them all, and not just look at thousands of records from my sofa. And there is something we should never forget: a digger only finds a record, but he’s not the one who created the music. Let’s be modest here.

As a White person who goes digging and producing in Africa, have you ever felt any tension with the local artists, especially when negotiating licences and dealing with fees?

Obviously I can’t deny the fact that I’m a White middle-class man living in France, who releases African music records. This is my reality and I do accept it. But first, this music existed before I came, so I’m not turning it into some Western-oriented stuff. Then there are many ways to do it, and it’s all about respect I guess. With Hot Casa, we always keep the original artwork, we try and manufacture with the best quality possible, aesthetically and sonically. We print a booklet with the interviews of the artists and people that were involved in the making of the record. We try and contextualise the album into the history of the country. As far as legal issues are concerned, we’re doing things right: we’re totally open and transparent about contractualization, and we pay an advance to the artist. But the main thing is about the human beings. Orlando Julius is like a grandfather to me!

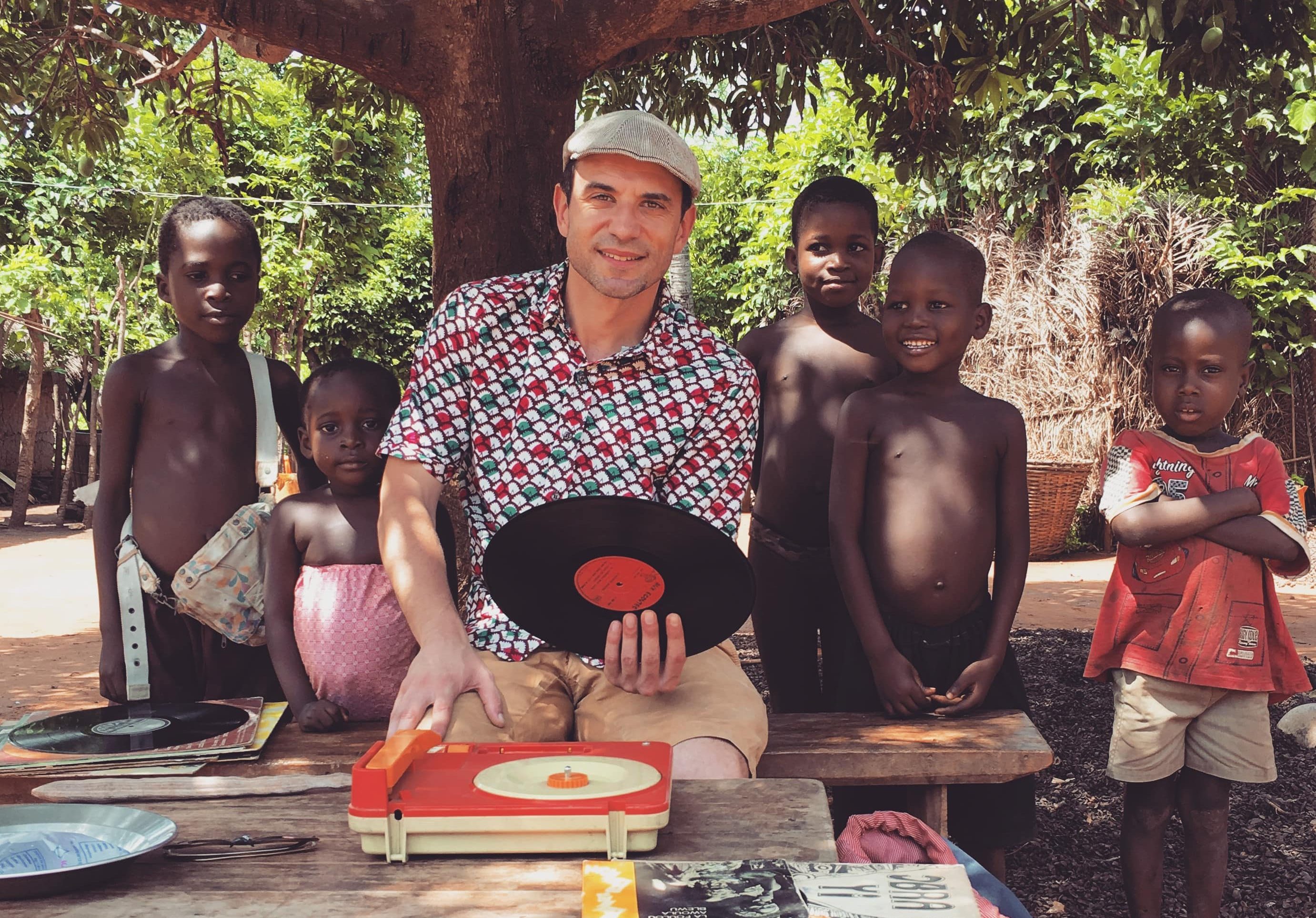

Digging in Lomé (c) Julien Lebrun

Would you say that these 20 years of heavy digging in Africa by Western DJ has had a social, cultural or economic impact on the local land, even at a very small scale?

For Hot Casa, we’re talking about 1500 to 2000 copies of 15-artist compilations. So we’re not pretending to save a musical scene, or making it alive again just with our records. But we’re trying to equally share the small profit these songs can produce. And in the last four years, there have been a few new diggers, labels or record shops, especially in Benin, Ivory Coast, or Nigeria with the recently founded label Odion Livingston.

Do you think that reissuing of music from the 1970s can be a way to promote and highlight a sometimes forgotten heritage?

Yes, but the strength of music now lays in electronic music. So we at Hot Casa may be the old-fashioned guys, with our obsession with exploring the past, while everybody else is into the future! [laughs]

Why do you work mainly with vinyl?

The afro music scene is very specific: digital sales and streaming are very weak, because the average 30 or 40-year old guy won’t be using Spotify or Deezer. They want to own the vinyl edition. Digital listening habits are very different, too, and you can see it with the Vaudou Game LP: the single track has way more listens than the rest of the album.

Napo from Mi amor at Lomé La belle (c) Julien Lebrun

Have you ever thought about exploring other African countries, or other regions in the world, as you regularly do in you weekly radio show “Hot Radio Casa Show”, broadcast by Le Mellotron ?

We don’t want to put frontiers, as long as it concerns jazz, soul or funk from the ’70s and ’80s, which is an endless territory for digging, I think. Because this music is found everywhere: Finland, China, Singapore, Thailand… all the GIs that used to go to Asian clubs were listening to James Brown, and it has eventually left a trace. The only thing we don’t want to do is exploring the countries that other labels already worked with.

On this point, what are your links with the other afro music reissue labels like Analog Africa, Soundway, Superfly, Teranga Beat, Awesome Tapes From Africa, etc.?

They’re competitors but we have a friendly relation with them. We are truly interested in what the others are doing, and we try and find a way not to release the same music. And without their work, we wouldn’t have the afro scene we’ve had for 10 years now, with such an attention to the object, biographies, pictures, mastering, tracklisting. When Soundway Records appeared at the beginning of the 2000s, they started to release very specialized records, whereas before them you would find compilations with very odd tracklistings, mixing everything that sounded afro on the same disc: Mali music with Kenyan and Nigerian songs… And today you still have people doing a bad job, like this Austrian label who popped up from nowhere and releases six records a month, not being transparent with licences, and offering a really bad mastering…

What is the economic model of the label, whose releases are mainly reissues of 1970s and 1980s albums?

We’ve found a balance, mixing between long-sellers – like Orlando Julius Disco Hi-Life released in 2007 and still selling very well – and the rest of the records that we mainly sell around the time they’re released. And like any label, we have to deal with handling stocks.

Roger Damawuzan at his home showing his ses mastertapes (c) Julien Lebrun

What is the average number of copies you produce for a record you think will be a long-seller?

If the original album is not referenced, we produce 1000 copies, and we do a second run of 500 copies. For Orlando Julius album, we released 2000 copies first because people know who he is now, and his music sells well. Then it depends on the audience: DJs only want dancefloor fillers, and when we find some, we produce 2000 to 2500 copies. The people who like to listen to the record at home, sitting on their sofa, will buy a record that tells a story. In this case, we release only 1000 copies.

Talking about stocking records, I can see many vinyls behind you. Where are you? [the interview was carried out through video-conference]

This is the basement at my place, with my personal collection, as well as Hot Casa records. I try and send them as soon as possible to our distributors over the world, so they don’t accumulate here at home!

Hot Casa is a small house, with old-style management?

Yes it is! We’re not Soundway Records, with the great media exposure they’ve had from the beginning, thanks to products that appealed to the Guardian or the BBC… and we don’t have they PR team either. Analog Africa have these advantages, too. Hot Casa comes from the digging sphere, and we belong to a culture that cherishes and has always known record fairs. And we generally hire a PR agent only for our new productions, not for the reissues. The rest of the job is done in-house, thanks the the network we’ve built in 15 years: independent record shops, distributors, etc.

THINGS STARTED TO GET PRETTY TENSE AND THE DRIVER DECIDED TO ESCAPE AND DRIVE THE TRUCK AS THE GUARDS WERE SHOOTING ON THE VEHICLE! LATER WE MANAGED TO ESCAPE AND ENDED UP WALKING TILL THE CITY. YES, WE DO LOVE DIGGING, BUT I CAN TELL YOU WE WERE NOT VERY PROUD OF HAVING RISKED OUR LIVES JUST BECAUSE WE WANTED TO COLLECT RECORDS…

With 20 years of digging, you’re likely to have experienced amazing moments. What would be the craziest one?

Djamel and I were in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, in 2011, only two months after the end of the political crisis when Gbagbo was kicked out and Ouattara was elected president [after a war that left 3000 dead people]. It was the wrong time for us, obviously… We had been digging 20 miles off Abidjan. As it was Ramadan time, and Djamel respects it, we had to wait for the sunset to head out to the city. It was curfew time, too, so there were no taxi-cars available, traffic was forbidden. We were next to a lake, in the dark of the night, attacked by mosquitos… Suddenly, we see a vehicle approaching: a truck full of chickens! There was room for both of us in the back, amongst the chickens where we would hide. There were many checkpoints on the route with armed guards. As we were driving towards Abidjan, more people entered the truck, joining us in the animals shit… At one checkpoint, the guards noticed someone’s head above the poultry. Things started to get pretty tense and the driver decided to escape and drive the truck as the guards were shooting on the vehicle! Later we managed to escape and ended up walking till the city. Yes, we do love digging, but I can tell you we were not very proud of having risked our lives just because we wanted to collect records… Also, one day, as Djamel was rummaging through dusty crates of old records, a scorpion climbed on his hand! Digging is a way of traveling, and it means also potential dangers, but what we prefer is meeting people and discovering new cultures.

As you’ve travelled around for some time now, what places in Africa would you suggest for someone willing to do a musical and cultural trip?

Africa is a huge and varied territory… But I would say Benin and Togo for the hospitality, the variety of landscape, the quality of the food, the music and a very strong and unique culture. And Ethiopia for the amazing beauty of nature, the ever-changing landscapes and the way people easily welcome you in their homes. And they have a very unique culture, very different from the rest of Africa: their own language, their own time system, their own alphabet, and they’re the only country that has never been colonized!

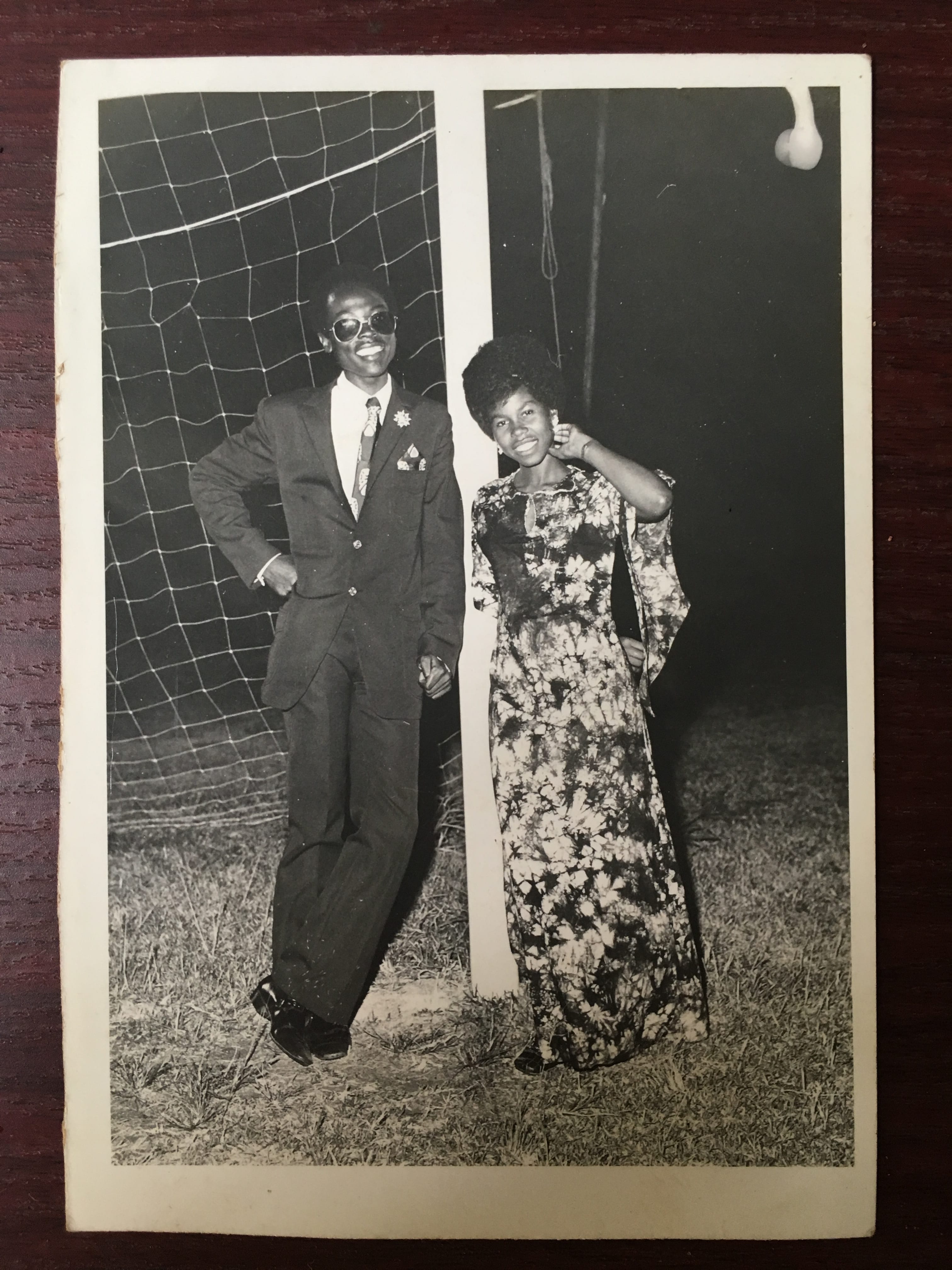

Roger Damawuzan & Akofa Akoussah, winners of the first “Festival de la chanson Togolaise” (Togo Songs Festival), oct 1971. With the authorization of Roger Damawuzan

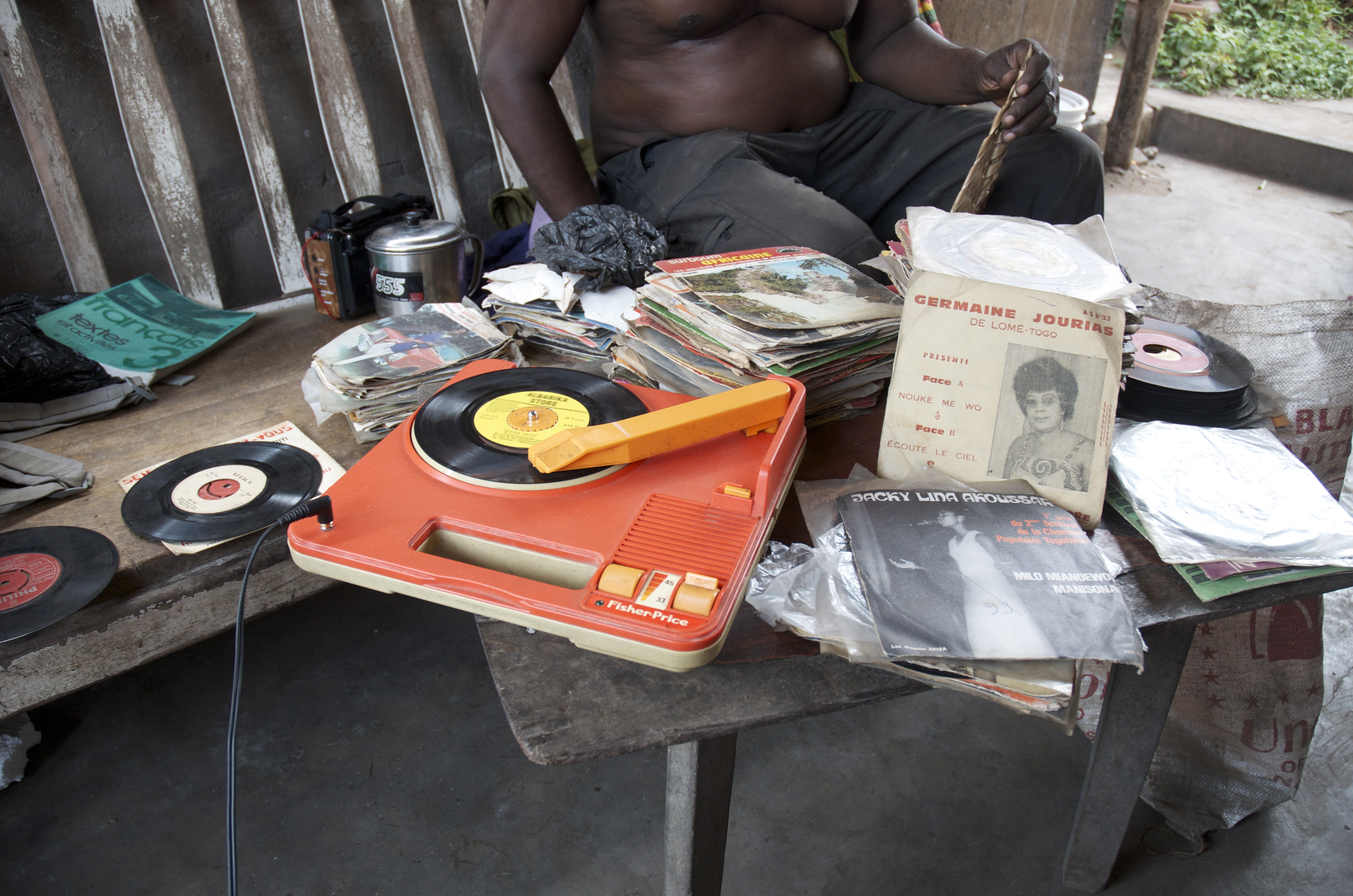

Lomé (c) Julien Lebrun

Lomé (c) Julien Lebrun

Digging in Lomé (c) Julien Lebrun