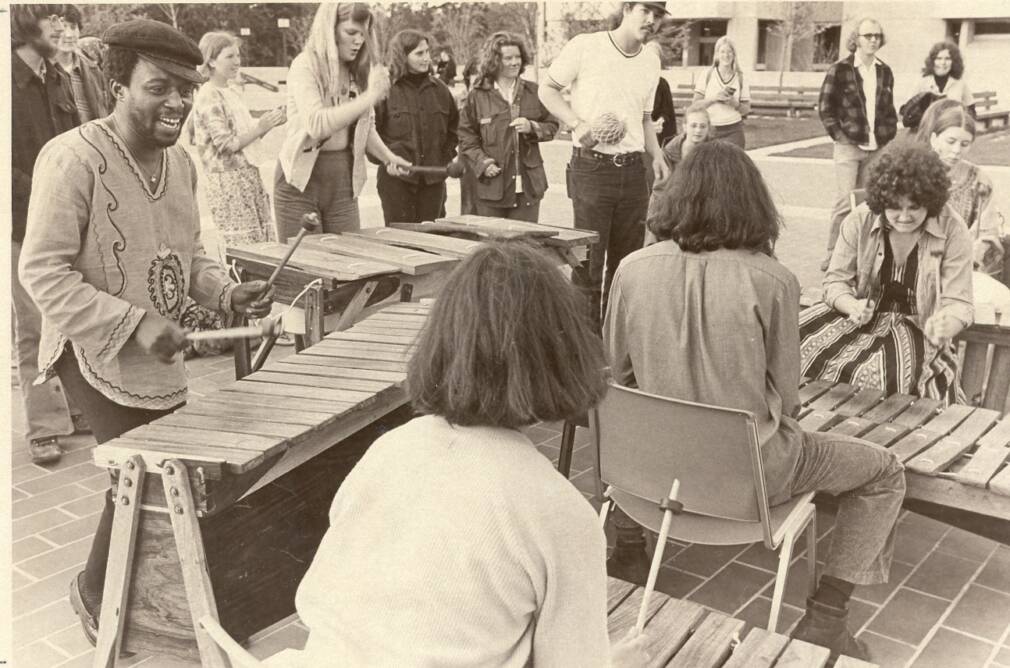

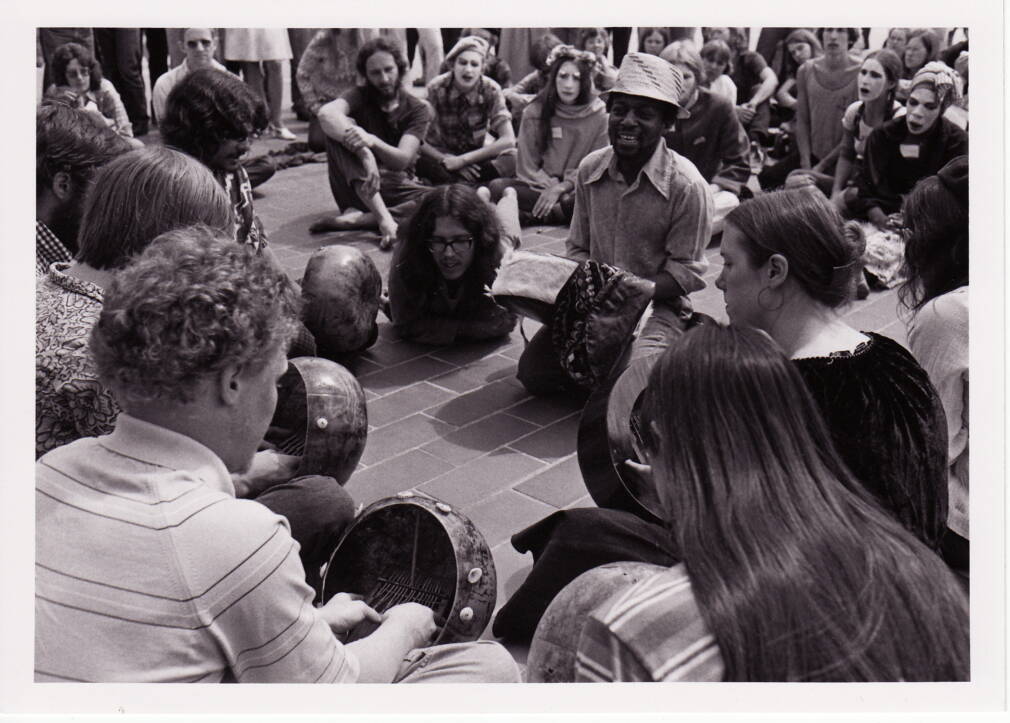

Dumisani Maraire devoted his life to the mbira. A young man plucked from his hometown of Mutare, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) after a curious American ethnomusicologist from Washington University heard his composition for the high school’s Christmas performance, Dumisani aka “Dumi” would go on to lead a life in-between worlds. Earning degrees, teaching at the University of Washington and Evergreen college, founding ethnomusicology programs in Zimbabwe, pursuing doctoral studies all while relentlessly performing mbira shows and teaching private lessons… Dumi’s cause was singular. Spread the magic of the mbira the world over.

Though devotion comes at a price. Like all great spiritual struggles, there is sacrifice. Dumi died of a stroke in Zimbabwe at the age of 54.

A quick note on the mbira. The mbira has existed on the African continent for thousands of years now, found from the reaches of the Kalahari desert to the edges of the Zambezi river, and popularized among the Shona of Zimbabwe. Mbiras are part of the lamellophone family, instruments with little tines, or “lamellae”, which are played by plucking. The plucking method creates overtones with a strong attack, but which die out rather quickly. However, the resonance of individual lamellae creates secondary vibrations for a rich harmonic complexity. Sound familiar? All this is not to begin to touch the spiritual dimension of the instrument, to which the author remains wholly ignorant.

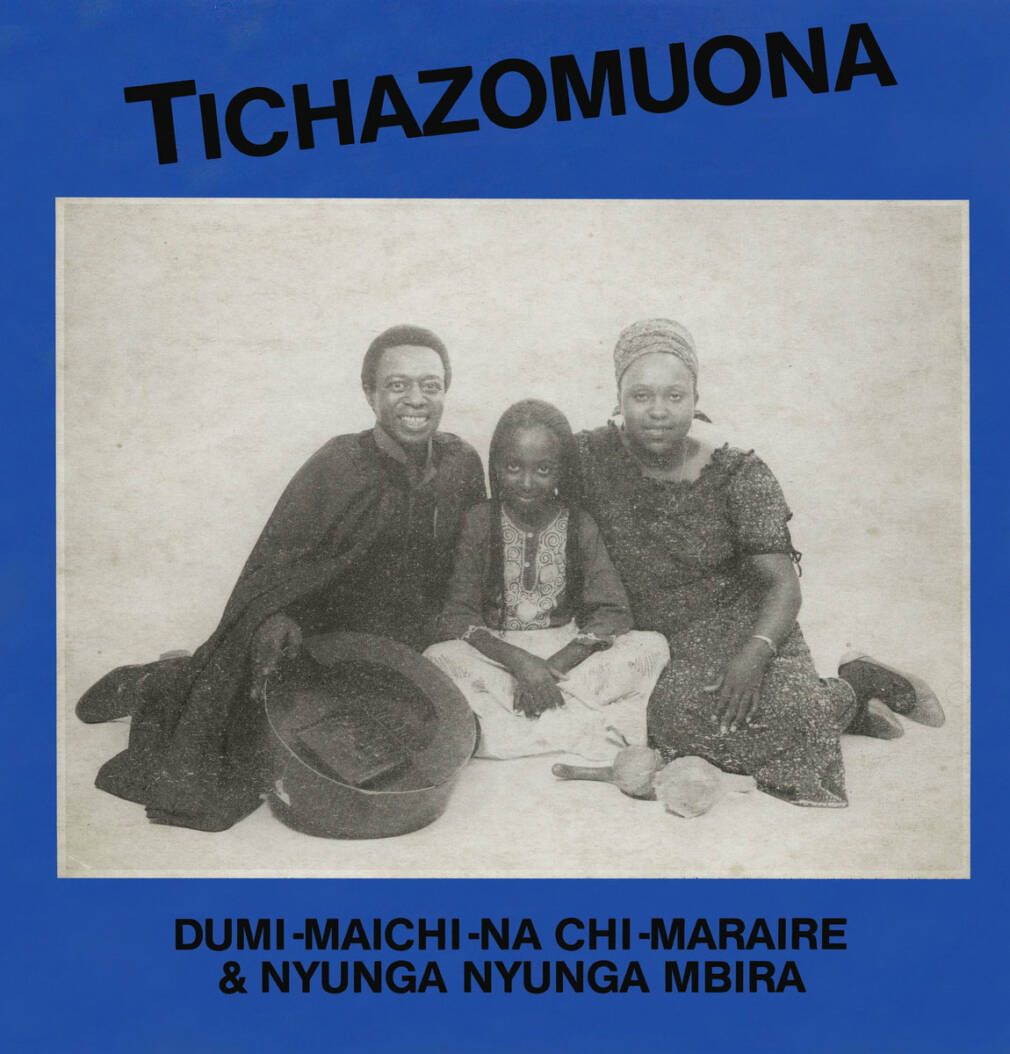

Dumi’s mbira of choice was the nyunganyunga, a 15-Note lamellophone named after the community from which it originated. Dumi himself personified the instrument on the credits of his 1986 album, Tichazomuona, soon to be reissued by Nyami Nyami Records. The album also includes Dumi’s wife, Chengeto Linda “Mai Chi” Nemarundwe and daughter, Chiwoniso “Chi” Maraire. This family affair, so beautifully captured and masterfully composed, is an emblem of modern mbira music. It’s re-release was also the impetus to reach out to another member of the Maraire family, Tendai Maraire (performing in groups such as C.A.V.E., Chimurenga Renaissance and Shabazz Palaces) to get a better impression of his father and the “secondary vibrations” of the Maraire family’s musical resonance.

“My Dad had no childhood,” Tendai told us, comparing him to Micheal Jackson in his relentless devotion to his craft and brutal nature of his early upbringing. Dumi grew up in colonial Rhodesia where the mbira was seen as a threat to the Christian hegemony of the colonial state. What was once a vital symbol of Shona spirituality was repressed and associated with evil spirits. Though this didn’t seem to discourage Dumi who in 1966, attended the Kwanongoma College of Music in Bulawayo, developing in parallel to music icons like Thomas Mapfumo and Stella Chiweshe. The social burden of pursuing the mbira in the time before Zimbabwe’s official independence in 1980 can’t be understated. Nor can, after accepting a professorship at the University of Washington’s ethnomusicology department from 1968, the pressure put on him as an immigrant to exceed expectations. Tendai speaks of his father’s love for adversity and responsibility edified in his father’s pugnacious will to reintroduce the mbira curriculum to schools upon his return to Zimbabwe in 1982. “When he went back to teach, he got rid of the Classical music curriculum to teach kids their culture,” Tendai explains.

Though generous enough to speak with us, Tendai admits that he didn’t have a close relationship with his father. Time, it seems, was the ultimate sacrifice his father made to his life’s work. It wasn’t until Tendai himself matured in his musical career that he realized the burden of living a life on tour, in the studio and inside the whirlwind of responsibilities that come as a public figure. Dumi’s precedent for the music had its penalties. “If Miles Davis was in town and we were having a show,” Tendai recounts behind a smile, “he’s going to Miles Davis.” On the aforementioned album, Tichazomuona, Chiwoniso, Tendai’s half sister who was 10 years old during her vocal recording on the title track, has her name slightly misspelled on the album credits. Note however, that when the Nyunga Nyunga Mbira was given credits on Tichazomuona it’s a picture of the family with the mbira rather than the instrument itself…

Chiwoniso would go on to receive many more credits. As early as 15 years old Chi joined a hip-hop trio, A Peace of Ebony, a first introducing mbira to contemporary beats. Later she joined one of Zimbabwe’s most popular groups, The Storm, led by guitarist Andy Brown who later became her husband. Her first solo album Ancient Voices, released in 1995, reached critical acclaim and brought the contemporary mbira sound even further. Another story of mastery, music and sacrifice. Her final track “Zvichapera”, a return to the traditional mbira sound, was recorded shortly before her death in 2013 at just 37 years old. “Me and her were tight,” Tendai said of his sister.

“Deep pools have become crossing points, crossing points have become deep pools”

Shona proverb

Tendai has his own story as well, intimately linked to the instrument that manifests in the lives of the Maraire clan. He told us the story of his introduction to the mbira. During a trip back home to Zimbabwe to establish a deeper relationship with his family, he hit an unexpected crossroads with destiny. It was during a baptism ceremony that one of the elders made a prophecy. Tendai’s eyes caught sight of an mbira in the room and the female elder instructed, “That’s yours. You’ll play it in more countries than anyone ever has before.” Tendai took the prophecy to heart. He taught himself to play and carries his mbira with him on tour and in his travels around the world. “When I got there (Zimbabwe) it called me and there was nothing I could do about it. It changed my whole life,” Tendai says, “It’s a gateway to a whole ‘nother dimension.” Listening to Tendai’s musical catalog, though it usually dabbles in experimental hip-hop, the mbira is never too far away.

“Music is the one thing that was the constant keeping the family afloat,” Tendai concludes as we wrap up our talk. He sees this latest release as a way of honoring his father’s purpose, preserving the knowledge and bringing it to a new generation. The family, again, having blurred lines between the individuals and the instrument itself. “The only sad part to me is that you don’t get to see him perform,” he mentions. No arguments here. Though Tendai hinted that while digging through his father’s affairs he found a vast collection of notes, manuscripts and VHS videos that could lead to an eventual documentary. The duty and the sacrifice continues. But Tendai is not daunted. “I know what my family means to Zimbabwe. They mean a lot.” Secondary vibrations.

Tichazomuona out May 5th via Nyami Nyami Records.