She is the feminine and feminist icon of West-African music: Oumou Sangaré, «the diva of Wassoulou », the name of the cultural zone between Mali, the Ivory Coast and what is now Guinea. Wassoulou, her mother’s region, is the forest lung of southwest Mali. Ever since her first album in 1989, Moussolou, Oumou Sangaré has been singing its rhythms. She now supports its economy by orchestrating, for example, the Festival International Wassoulou (FIWA), a free cultural event that draws more and more people every year.

Indeed, the United Nations Goodwill Ambassador for food and agriculture, who experienced poverty and hardship as a child in Bamako, is also a business woman : she owns a hotel in Bamako and has her own brand of rice. She is an international superstar who has never left her country. She was recently invited by Alicia Keys for a televised duo, and the 54 year-old woman is now cited as an example by artists such as Aya Nakamuraor Beyoncé, who sampled one of her most famous songs, Diaraby Néné, for the song Mood 4 Eva on the soundtrack of the film The Lion King : The Gift in 2019.

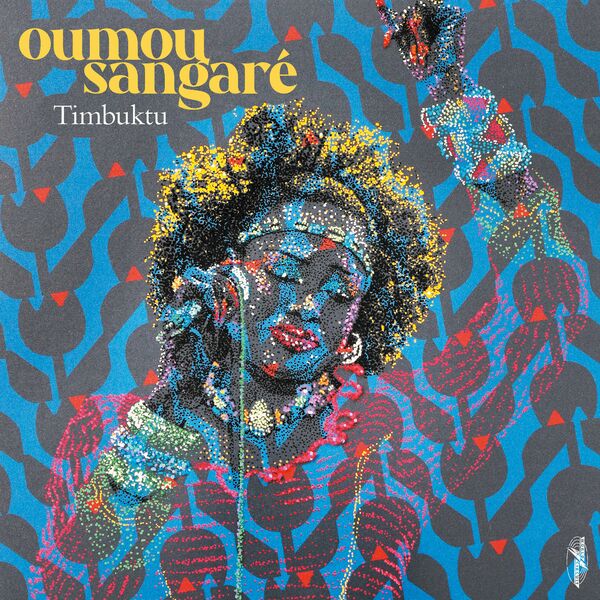

After an artificial electro album, Mogoya (2017), then a magical acoustic version of the same album (2020),« Wassoulou kono » (the songbird from Wassoulou) has now released the first album on her own label, Oumsang, her twelfth album: Timbuktu. An introspective opus that forges intimate sonic connections between traditional West African instruments and those linked to the history of the blues. Particularly between the kamele n’goni and its distant heirs the dobro and the slide guitar, played by Pascal Danaë : “My music, which comes from Wassolou, is traditional. But my doors are open. I welcome everyone with pleasure. I collaborated with Americans and with the English, while keeping my own identity. Pascal Danaë brought his knowledge without denaturing mine. He adapted to my rhythm.“

Even if the title of the album, Timbuktu, is a homage to the city in the center of Mali that has been constantly under siege since 2012 from Jihadist attacks, Oumou Sangaré has always sung about her native soil, Wassoulou. In fact, the very first song on the album, Wassulu Don, literally means “Wassoulou culture”. Most of the eleven songs on the album are about the singer’s highly singular experiences : her never-ending fight in favor of the advancement of women (Gniani Sara), solitude (Degui N’Kelena), or about the problems her fame brings her (Sarama), and which she encourages herself to overcome in Dily Oumou.

We talked about all this, but also about her project to build a school, about Bob Marley, about a memorable concert at the Sydney Opera House, and about her recent role as a granny in a film as well in life.

PAM : You recorded Timbuktu in Baltimore, in 2020, during the first confinement. I heard that you immediately liked this northeast city port and even bought a house there. Can you explain why?

Oumou Sangaré : In March 2020, after the FIWA, I went to the United States. I was only going to spend two weeks there but because of confinement I had to stay much longer, seven months in fact ! I stayed three months in New York first. It’s a beautiful city but it’s exhausting because it’s awake 24 hours a day, the city never sleeps. I needed to be alone, in a calm spot. So I started looking for a house. I looked everywhere, and when I arrived in Baltimore, where I didn’t know anyone, I felt really good : it was green and there was less noise. I said to myself that I would stay there, and then someone told me that if I felt so good there was a reason for it: the first place Black people to set foot in America was in Baltimore. I said : ‘What ! Wow ! There is something going on here, some spirits at work.’ So maybe that’s what attracted me to stay there.

And you asked the kamele n’goni player Mamadou Sidibé to join you there ?

Once I’d settled in, I started to think. Mamadou Sidibé was my very first n’goni player. Then he worked with my idol, Coumba Sidibé, who took him to the United States. But then Coumba died, sadly. But he stayed there and it’s been 25 years now. One day I called him in Los Angeles where he lives and I asked him if he’d like to come and try to create something together, since the borders were closed and we were stuck there. He answered : ‘That’s a great idea, I haven’t touched my n’goni for three months, just send me the tickets!’ The result : for three months, day and night, we were free ! We slept, we woke up, we created music, that’s all we did. No pressure, no stress. It was incredible. Other than my first album, I’ve never had so much time to spend making an album than on this one.

Is this why you feel this album is “the most intimate one” in your discography ?

Yes! Because, you know, I’m always on the move, always working. And I wrote this album calmly, peacefully. I had time to really think about it, to draw out the emotions inside of me, to look back at the past thirty years of my life. Because of all this I could put more of my heart into it.

And even though I was suddenly cut off from my family and friends, while the country was doing very badly, I found a lot of positive things during the confinement. I learned things about myself. It was as if I had been up in the air and now I had my two feet on the ground. I’m always surrounded by a lot of people, and here I was alone and able to contemplate my life. I took my time in the kitchen, cooking meals, I was myself.

Can you tell us about the history of the kamele n’goni, this string instrument with plucked strings that comes from the harp family, and which is the foundation for all your songs ?

The rhythms of Wassoulou music are partly inherited from ancestral rites, the brotherhood called “Donsow” ( “Donso”, singular), the brotherhood of hunters. And the emblematic instrument of this music is the donso-ngoni, the healer’s “hunter’s harp” of the brotherhood of hunters.

In the past, young people (“kamele”) were not allowed to dance to this instrument. So in the 1950’s or 1960’s, they created a similar instrument which they played differently so they could dance to funk, jazz, rock, everything ! It was a huge scandal! Especially because since they spent their nights dancing, they couldn’t get up in the morning to work in the fields. Young people fought with the elders until they were finally allowed to play it, and today the kamele n’goni, “the young people’s harp”, is played everywhere in Mali and all over the world. Mamadou Sidibé fabricates them in the United States. He also has a lot of students. When Americans play the n’goni correctly, it sounds like the way it’s played in Wassoulou!

I’ve heard that you would like to become a teacher. How is your project coming along to build a school to teach the young about the various artistic professions?

I’ve been working on it for two years now. In 2019, in Yanfolila, I inaugurated a tourist and cultural complex with forty bungalows for my festival, the FIWA. The encampment allows festival-goers, VIPS, employees and volunteers to be lodged there, but it’s active all year long. This is where I want to create an institute to teach young artists and also to train administrators and technicians.

I want to share the little that I know with people, I don’t want to take it into the tomb with me. I didn’t get the chance to go to school, but the fact of working every day gave me some skills. I know, for example, how to stand in front of an audience that doesn’t understand me and to draw them into my world. This is the kind of thing I can pass on.

In the songs “Sarama” and “Dily Oumou” you evoke once again the problems that come from being famous : jealousy, slander, betrayal. Do you still suffer from these things today?

At first it really hurt me. But now, after a thirty-year career, I’ve moved on from all that. It’s difficult to rattle me, I’ve become as hard as cement ! (Laughter) I’ve heard the worst things said about me : that I was a Muslim woman, that I had made porno films… Why? Because after ten years into my career I started building a hotel in Bamako. I said : ‘Oh really? There’s that much money to be made in porn?’

On your very first album you were already fighting against the patriarcal tradition that allows polygamy, forced marriages, and excision. You say that you risked your life by doing it. Can you tell us more about this?

I was highly criticized and often even threatened. People would say : ‘Who do you think you are, questioning polygamy.’ But my chance was that I became very popular, which made me untouchable. Even the angry elders couldn’t say anything anymore because their daughters would say to them : ‘If it’s not Oumou Sangaré who’s coming to my wedding, I’m not getting married!’ (Laughter) That’s my greatest reward: to have raised awareness, especially in young people.

Do you have other musical memories from your childhood and adolescence than the “soumous” (baptismal or wedding ceremonies) hosted by your mother, who was also a singer, and in which you also participated ?

We danced a lot to Bob Marley, it was incredible! We didn’t understand the words, but we danced all over the place when we listened to him sing. I even remember when Bob Marley died, I didn’t eat for several days. I was 13 years old and I couldn’t stop crying. Until someone said to me : ‘What’s your problem ? Did you know Bob ?’ (Laughter)

You’ve sung in places like the Sydney Opera House, the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo and even in Central Park in New York. Is there a place in the world that really impressed you

I’m still quite moved when I think about the Sydney Opera House. It was over 25 years ago. I was only supposed to do one concert there, but an Australian television crew came to Wassoulou to do a story about me first. And because of this, to my great surprise, they sold twice the number of tickets. So I had to do two sold-out concerts there. At the end, people were showering me with white flowers, the whole stage was like snow, it was beautiful! I rarely talk about it, even though I was incredibly moved by it.

Were there a lot of Malians in Sydney?

No! When they came to pick me up at the airport, I saw only one black person, who praised me by saying “Sangaré bari!” He was probably the only Malian man in Sydney at the time. (Laughter)

You have recently made your debut as an actress in the new film by the Franco-Senegalese director Maimouna Doucoure. What are your feelings about the experience?

Maimouna asked me to play the role of a granny. I said : ‘Ok, I’m already a granny with three granddaughters and I love it because my princesses give me so much love, so why not ?’ Plus the story is really touching : it’s about a young albino girl who is in fact very close to her granny. We did three weeks of shooting here in France, and I loved it. Maimouna told me: ‘You’re a perfect artist, you even bring tears to my eyes.‘ She thinks I’m too talented. (Laughter)

The album Timbuktu was released on May 6, 2022.