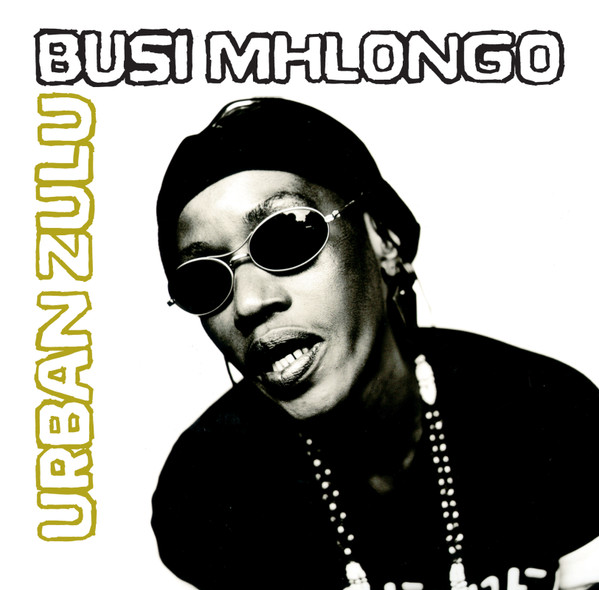

Writing about Busi Mhlongo is quite an emotional task and it’s this constant negotiation between language’s failure and the most optimistic part of me that absolutely needs to deliver the truth about Mhlongo’s importance in the cultural heritage of South African musical traditions. When Matsuli reissued Mhlongo’s iconic, golden bread album Urban Zulu on vinyl, I was one of many people who felt relief and excitement. Busisiwe Victoria Mhlongo affectionately and respectfully known as ‘Mam’Busi’ was born on 28 October 1947 at Inanda, near Durban in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her singing career began in local choirs and concert groups and like many great black musicians, her artistic form started in the church and it was encouraged within her family structure. In an interview with Jamie Renton, Mhlongo talks about how she started singing at a young age and the role that community played in cultivating her artistic confidence: “My family was very religious and so we would all gather together to go to church every weekend. And after church it was party time! All the people who had gone to the church would come home and want to eat and sing. The kids would have to perform. We would join in with our uncles singing the traditional songs and so singing became a part of my life. I didn’t know that it could be a profession, for me it was my role in the family. I would sing whenever my voice was needed, whether it was a funeral or a wedding or whenever.“

Mhlongo moved to Johannesburg to start her career with Gallo Music and recorded under the name Victoria Mhlongo before becoming Busi Mhlongo, the infamous Maskanda urban punk king. As a genre, Maskanda developed as a result of Apartheid’s migrant labour system that saw the migration of black people from the rural settlements to cities like Johannesburg that became the epicentre of South Africa’s gold rush. Maskanda became a travelling traditional sound with roots in rural cultural life. In the movement of black people into the city, Maskanda went through its own transformation, entering the hustle and bustle of township life, shebeen halls, hostels and inner city venues. This sound entered the urban mainstream through quite masculine spaces hence Maskanda became unfairly accredited to Zulu male musicians, when in fact, this music originated in female gourd-resonated monochord songs that were transferred and given an acoustic life on guitar. Black women’s contributions to Maskanda was lost as the style moved through the hands of male migrant labourers and particularly male friendly spaces. So, when people like Busi Mhlongo forge their way into this sound, it’s not only about her undeniable artistry but it’s a historical recognition that Black women were not only purveyors of Maskanda but also at the forefront of its inception and its ever changing creative sound. I wrote elsewhere that “through her warm transgressive personality on stage, Mhlongo transformed the masculine sensibilities inherent in Maskanda’s roots and sang back to the often feminine, wailing voice of its male singers and she stayed true to the rhythms, string foundations, vocal layers and chants inherent in this music and transcended it largely creating her own distinct sound and audience.”

In 1963 Mam’Busi released a national hit track My Boy Lollipop and immersed herself in musicals and worked with various jazz groups like Earl Mabuza’s Big 5. In 1968, she travelled to Maputo, Mozambique with the African Follies and that trip became the inception of her decades long nomadic status that extended to her time in Lisbon, Portugal where she performed with a Portuguese army band Conjunto Juan Paulo. Mhlongo married South African musician Early Mabuza and they relocated to London in 1972 and joined the burgeoning scene of South African exiled musicians and sang for the iconic afro-rock band Osibisa. Her versatility and super intelligent approach to composition and song came from her rooted knowledge of South African musical traditions, rhythms and performance. Living abroad and the exposure to black diaspora musical styles added to her rich palette. It’s no surprise that her solo albums include sophisticated interpretations of reggae, funk and soul nurtured by the labouring efforts of her dedication to Maskanda.

Following her time in London, Mhlongo made a move to Canada and remembers how this time marked a shift in her career and visibility: “It was here that people started to notice me. I became involved in the theatre and was respected by theatrical people, artists and other musicians.” Mhlongo returned to South Africa in 1979 on tour with South African singer Letta Mbulu. This coincided with a turbulent time of anti-apartheid resistance and state violence: “Then I returned to South Africa and things were so tough there, really tough, tough, tough. I got the spirit, the energy, the anger and frustration with being in South Africa. People were dying left and right. I was trying to make music which expressed my feelings about this and the songs for my first album just came out of that. I was talking about nothing but what I saw in South Africa.”

For much of the 1980s, Mhlongo based herself in the Netherlands where she became the darling of a burgeoning “world music” audience. She performed with a Gambian band Ifang Bondi, Salif Keita and Manu Dibango in her time in Amsterdam. She lived much of her life continents away from her country of birth but later returned to South Africa and had to weather the harsh conditions that she encountered in the local music industry. Loved, adored and known all over the world, she came back to a tired reception, a distressful situation for someone whose sound is unequivocally local. In 1990, she recorded an album in Holland with a group of Dutch musicians under her band Twasa: “I couldn’t record in South Africa because of how bad things were there. But the album really opened things up for me in South Africa and let people know where my head was.” In between this time leading up to her most iconic album, Urban Zulu, Mhlongo collaborated and featured in tracks with other South African musicians and slowly tended to her wounds bred in part by the mess of mixing art and business, and negligent treatment of the showbiz oligarchy. The turning point in her career came through her collaboration with record label M. E. LT. 2000: “My whole life took a new direction because I got a chance to say. ‘This is what I want to do.’ At the time I was very angry; I didn’t trust anybody. I had been through a lot of bad experiences within the music industry, being ripped off over royalties and all of that stuff.”

When Urban Zulu came along in 1999, it solidified Mhlongo as a living monument of South African musical traditions. Mam’Busi sunk her teeth into the music backed by a stellar constellation of musicians. It is a beautifully produced album and much of its success has to do with the creative and intelligent production decisions and collaborations that found an incredible way of crafting the entire album and its sound around Mhlongo’s colossal voice. She could wail with the ache of a suffering child, groaning in chants mimicking the trance inducing voices of Nguni traditional healers in conversation with their ancestors. She could reprimand and warn younger generations about the need to respect parents in the most stylish ululating rhythm in tracks like ‘We Baba Omncane.’ Mam’Busi made you ask existential questions about the sort of life that brings this kind of art and sound out of a human being. I think it’s important to note that she had a spiritual gift for song that came with her practice and calling for ubungoma (traditional healing). As an initiated Sangoma (traditional healer) she used the stage as a space for healing and often chanted in the sacred Nguni healer vocal co-ordinations. We are so lucky to have such an extensive recorded video archive of her sacred performances where she would command the entire gig, draped in isiZulu regalia and the sacred beading that signifies the presence of her ancestors. The acoustic guitar Maskanda foundation in some of the tracks in Urban Zulu is the glue that holds together the intricate inclusion of other genres like funk, reggae and soul. Her soprano long tail notes in the beginning of her tracks became one way of recognising a Busi Mhlongo joint from its horizon before her precious basslines land with perfect form and both feet on your chest. Mam’Busi was like a self-cleansing ocean with a sound that stood in its magnificence, catching the wave of each generation with her originality: “if you cannot touch the youth it’s very painful, it is like having children who you cannot communicate with. The rhythms (of Urban Zulu) helped us with this because the Maskanda rhythm is not so far from the rhythms of drum ‘n’ bass or hip-hop.” She understood the importance of versatility without compromising sonic principles and showed that she was a musician of all ages. When I think about her track ‘Uganga Nge Ngane’ and the chaos that erupts whenever that track plays in the gatherings of black people, it’s a feeling that cannot be fully held by the limitations of language.

As writers, a lot of times we find ourselves in absolute discomfort when dealing with big figures who are no longer with us, we are terrified of misrepresenting them and so dedicated to the many truths of their lives. For someone like Mam’Busi the narrative is in the music and her life is lyrically laid out in the bare compositions that signal a life that knew both the joy and suffering of living. She sang about structurally induced violence in black communities and about the long list of maggot-like social ills, eating away the spirit of black people in South Africa. She sang about love in traditional vernacular blues with utmost sincerity and cheek. The track Yaphel’imali yami is about a lover who never writes her back and Mam’Busi sings this track in the most aggressive and playful masculine groaner voice. She took a colloquial form within South African musical traditions of using everyday speech lines to create this unforgettable song that matched the speech of everyday people and their experiences. It was my favourite track for the longest time and the symbol of intergenerational group pride amongst black women.

Mam’Busi was a brilliant performer and the truest reflection of the genius and preciousness of Southern African performance traditions. She has always been the promise of individuality carried by a voice that is the energy that moves music. Without a doubt she wore her heart on her sleeve and sincerely embraced the courage of vulnerability and never minced her anger for the vicious cards that life dealt her. In another article about Mhlongo by Niren Tolsi, South African singer and close friend to Mam’Busi, Thandiswa Mazwai talks about her emotional transparency: “Anyone who knew Mam’Busi knows that her tears were always nearby. She cried a lot – about years she had lost with her family, about what was owed to her by audiences and record companies [who she felt never paid her the money due to her], about death.” She cried tears for her husband South African musician Earl Mabuza whose funeral she could not attend. Asking anyone to build a bridge over such a tragedy is an impossible task and this particular hurt stayed with her and seeped into the music, together with her many scars of being in the music industry.

Niren Tolsi rightfully remarks: “[South Africa’s] generally somnambulist approach to local genius had extended to a diminutive woman, with a roaring voice and temper, who had claimed and subverted the patriarchal space of the wandering Zulu troubadour, the maskandi.” Her insider-outsider status is complex, and much of its complication is attributed to music industry, the brutality of the Apartheid regime and the disorientating post-Aparthied failing dream. On the 15th of June 2010, Mhlongo succumbed to a long battle with cancer, leaving behind her only child Nompumelelo Elaine Mbuza-Black.