Francis Dordor is not new to the subject. Formerly editor-in-chief of the music magazine Best, and then reporter at the Inrockuptibles, he has already devoted several books to the man who brought reggae to the world stage, and popularized the Rasta message at the same time. This new chronological biography is carefully documented and puts Marley’s trajectory in its social, political and historical context. It gives the character an even greater weight, by rooting him deeply in the history of Jamaica, haunted by the ghosts of slavery, and in the history of Third World countries, which at the same time are trying to extricate themselves from the (post)colonial grip. His story, punctuated by the artist’s discography, also allows us to understand how much the lyrics of his songs, hummed by all, resonate with his life and the chaotic situation of his country.

The author looks back on his encounters with Marley, and his relationship with “The Last Prophet” of our time.

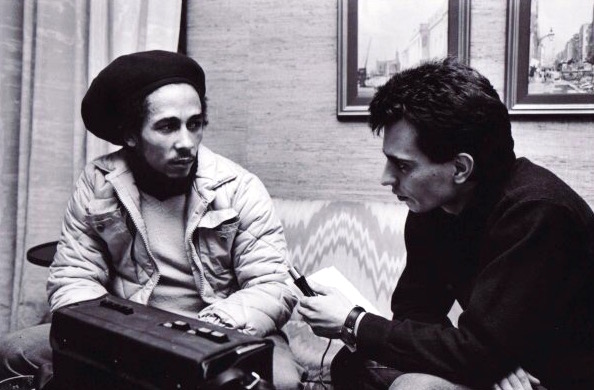

When did you first meet Bob Marley?

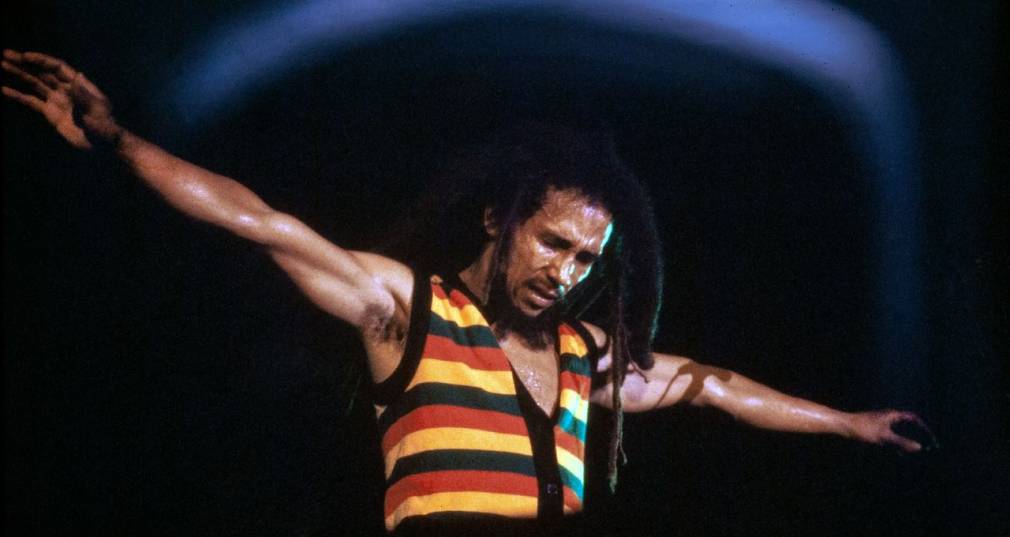

Back in July 1975 in the lounge of a large London hotel, the day after the Wailers’ concert at the Lyceum (from which the Live album was taken). Marley was giving a press conference attended by a large delegation of journalists from all over the world, some from New Zealand. I was a young reporter for the monthly, Best. That was the moment when everything changed for him, when he suddenly turned from a specialist’s hobby into a global phenomenon. I have two clear memories. The fact that he showed up in front of the press in the same outfit – a faded denim outfit – that he had worn the day before on stage. He had obviously not slept and had been out in London’s trendy clubs all night. The second was the awkwardness I caused by asking a rather silly, if innocent, question about the recently deposed and imprisoned Emperor Haile Selassie. I asked him if he was going to “free the Negus“. Except that everyone understood “free the niggers” which is not exactly the same thing. Bob tried to respond in a diplomatic way. But there were members of the London branch of the Black Panthers in the room and that was less cool. I actually realized the misunderstanding when I read the Melody Maker report. I took the trouble to write to the paper to clear up the misunderstanding and my reply was published the following week.

And your last meeting with him?

I had the chance to meet Bob Marley several times, in London, Paris, Kingston, and to follow him during the last 5 years of his life, those which correspond to his meteoric rise. The last meeting was in April 1980 in his headquarters at 56 Hope Road in Kingston. I had to wait a week before being able to access the Holy of Holies. Every morning I arrived in the courtyard of this old colonial residence that had belonged to Chris Blackwell. But he was never there. The Zimbabwean flag was flying in the window. Bob had brought it back from his recent trip to Harare where he had participated in the celebrations of the birth of the new African state, formerly Rhodesia, which had become independent after decades of apartheid and a bloody civil war. On the front lines, fighters from ZANU, the liberation army, were storming the streets to the sound of the song “Zimbabwe” that Bob had written for the Survival album. I felt like I was accompanying a moment in history. It was spring. The beginning of mango season. There was a sweet euphoria in the air. Reggae was the music of the moment. From the Clash to the Rolling Stones, everyone was playing reggae. The Rastas were no longer hiding. They, who until now had represented the dregs of society, were beginning to find a certain legitimacy on the island. Even if the political situation was still very chaotic, the success of Bob Marley and other artists seemed to open a new horizon. I spent my days at the beach, my evenings in the sound systems, waiting for a hypothetical green light. Which didn’t come. Every morning I passed by Hope Road to see if his BMW (chosen because of the acronym that corresponds to Bob Marley & The Wailers) was parked or not. Finally, after a week, he received me in his office on the second floor. The interview was brief. And I, who had known him to be sometimes suspicious, sometimes warm, even friendly, found him to be brittle and hasty. It was quite unsettling. At the time, I didn’t know – everyone did, except for his wife Rita and Blackwell – about his health problems. There had been that scare with his foot injury, but since then everything seemed to be fine. He still invited me to lunch with his brethren. After the meal (fish cooked in coconut oil, callaloo and breadfruit) I asked him if we could resume the interview. He answered that he didn’t have time. But he still went down in the afternoon to play soccer in the yard. I kicked the ball around with him and his brethren. That’s when I realized how much fear he inspired in everyone around him. After that I managed to sneak into the small studio in the back of the house where Errol Brown, the sound engineer, and Chris Blackwell were finishing mixing Uprising. That’s where I first heard “Redemption Song”. Suddenly Bob walked into the studio. When he saw me, he frowned like, “What’s this white guy doing here?” Then he closed his fist, held out his index and middle fingers in my direction like it was a gun. All I could do was smile stupidly at him and extend a hand. He looked at it and then, shrugging, tapped it. That was the last contact I had with him. Two months later, I saw him one last time on stage at Le Bourget in front of 50,000 people. A stage he would soon have to leave for good.

How did you end up in that famous soccer match in Paris where he injured his foot (and which was the starting point of his illness)?

The idea for the soccer game, and I don’t mean that in a boastful way, was mine. I knew Bob’s love of soccer. Every time he traveled, he would try to find a field just for the pleasure of kicking the ball. Shortly before the Wailers’ first concert in Paris, in the spring of 1977, I talked to Jacky Jakubowicz (the one from the “Jacky show” who was press agent at Phonogram at the time) about it. One thing leading to another, the thing was set up as a promotional operation. TV crews were invited to cover the event, namely a match on a field near the Eiffel Tower between the Wailers and the “Polymusclés” team, made up of people from the Parisian showbiz. But as the Wailers were not numerous enough, a few journalists, including me, came to complete their numbers. Anyway, the Wailers, even with 6 people, were essentially playing among themselves. It was a pleasure to see them play with grace and technical finesse (especially Bob) with their dreadlocks gathered in a woolen cap, half-gazelles, half-aliens. During the first half, Bob was tackled by a big guy from the other team. He went limp and eventually left the field. While still continuing from the sidelines to be in the game. That’s when his health problems started.

Your favorite track?

If I had to pick just one from the list of my favorites, I’d have to say “Slave Driver” from the Catch A Fire album where I discovered reggae, the Wailers and a whole culture. There is madness in this song. A madness that responds to an alienation. Marley’s stroke of genius is obviously to have been able to link his personal situation and that of his fellow human beings who endured 400 years earlier as Africans taken as slaves to the islands of what was then called “the New World”. It was with this song that I finally understood, and even felt, a history that had been deliberately hidden from me and of which I had until then only a very vague knowledge. This is what makes me think that songs like this should be studied in schools and universities to bring everything up to date.

Why do you think Marley is still so relevant?

It is enough to look at the recent events to realize how Bob Marley remains a burning topicality, how his view on the world remains in many ways prophetic. One example among others: the last album released during his lifetime is entitled Uprising. When I see what is happening in Iran, Iraq, Egypt, Lebanon, Chile, Hong Kong, Algeria, France, Guinea and elsewhere, the connection is quickly made. When Tunisians rose up against the Ben Ali dictatorship, I noticed that some of the demonstrators were holding up signs with some of the lyrics from the song “Babylon System,” including the phrase “we refuse to be what you want us to be.” I would add that Bob Marley remains one of the last universal figures in my opinion. “In the name of what do we fight for emancipation if not in the name of the universal?” asks the philosopher Francis Wolff. Before answering: “When you reread the texts of the peoples who freed themselves from the colonial yoke or slavery, Toussaint Louverture, Frantz Fanon, Nelson Mandela, etc., they did not fight to enslave their former masters, but for a world without master or slave.” Bob Marley is here too.