On October 2, 1979, Bob Marley & The Wailers released Survival. A Pan-Africanist work like never seen before, which included the seminal hit “Zimbabwe”.

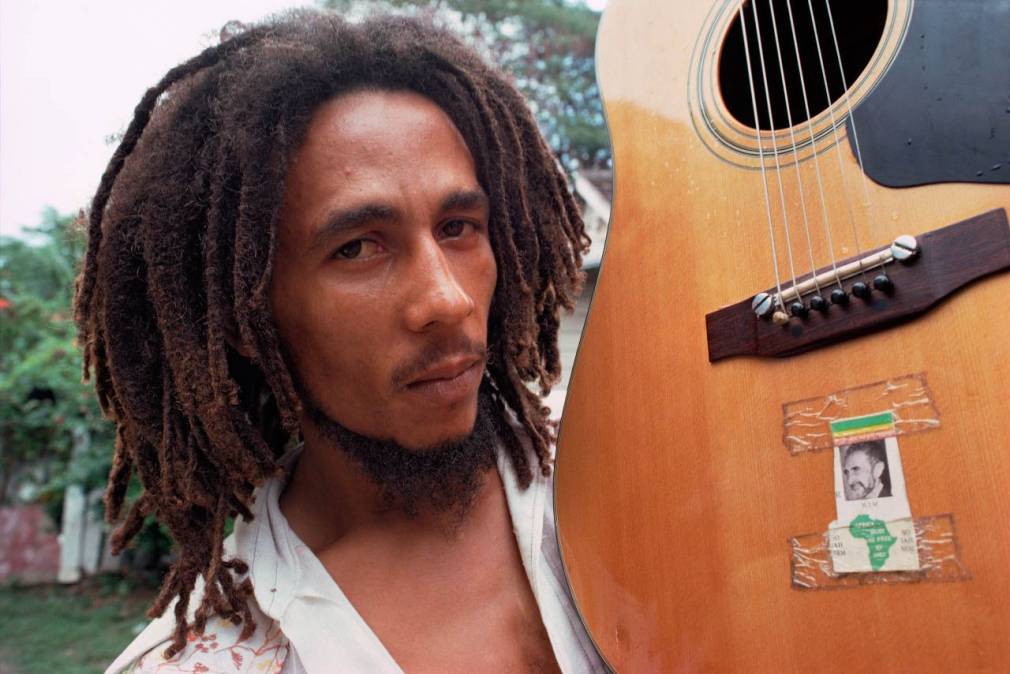

Bob Marley held somewhat the same vision as André Gide: “If it can be saved at all, the world will be saved by rebels.” When the Jamaican singer and songwriter looks at what he calls “the survival of the world” in the album Survival, he is still a rebel, albeit already safe from his most troubled years of his youth in the slums of Jamaica, where he was literally struggling to eat and hence, survive. In 1979, Marley is a well recognized and established artist. With his past five albums, he’s been supported by the mighty Island record label and by Chris Blackwell who even offered him a huge house on 56 Hope Road, in the upmarket neighborhoods of Kingston. But to literally ensure his own survival, Marley had to leave home for several years. On December 3, 1976, he miraculously escaped an assassination attempt at his home on Hope Road, which forced him into exile in London and then on to the Bahamas.

Back to Kingston, live and alive

Three years and two albums later, he returned to record in Jamaica, and finally spoke out about this landmark moment in his life on “Ambush in the Night”, the closing track on Survival, in which Marley tells how he owes his survival to “the power of the Almighty and the hand of His Majesty [Haile Selassié]”. A lyrical conclusion to an album which opens with the whisper: “A little more drums!” gently requested by Marley at the start of “So Much Trouble in the World”. It’s as if the singer had been caught red-handed in the act of his quest for perfection, giving orders to the sound engineer before going on to sing about this world’s disorder and imperfections. These sort of spontaneous outbursts are rare on a studio album, simply because this type of commentary is usually made during the mix process, when the microphones are turned off. But Marley wants to recreate a “live vibe” on this record, a highly organic and festive atmosphere of celebration on his return “home” – to his new Tuff Gong studio. “I have amazing memories of the Survival sessions,” said Dean Fraser, a highly sought after saxophonist in Kingston to this day. “There was complete harmony between us. We were all bursting with ideas and energy! We even composed a double intro for the track “Wake Up And Live”!”

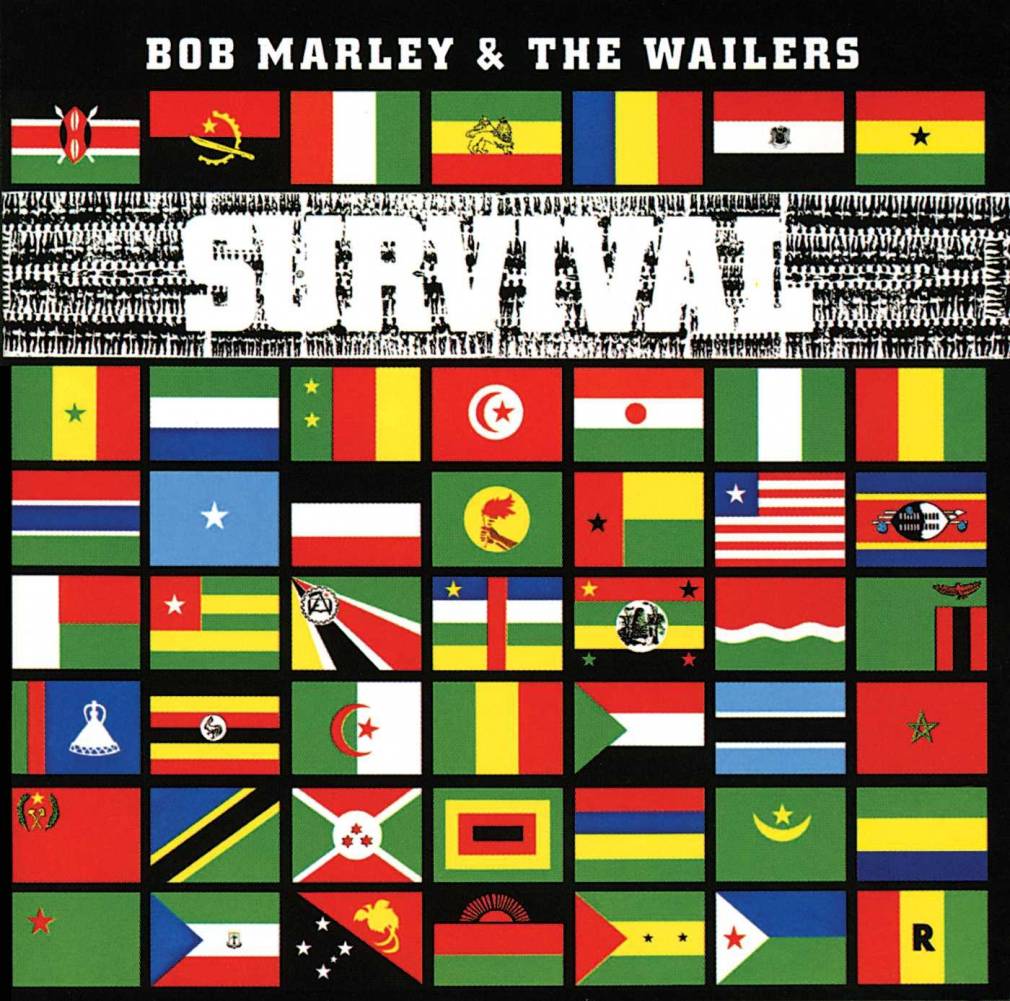

The track sounds almost like a concert in which Marley even drops the singing at one point to ask all of those present, “how is it feeling over there?” before Fraser launches into an improvised sax solo. This free-spiritedness is probably down to the fact that Island producer Chris Blackwell withdrew more and more to allow Marley to manage his own musical affairs; but also due to the collective energy that the singer instilled in a project that he initially wanted to call “Black Survival”, before finally deciding that his music was “for everyone!”Marley nevertheless believes that survival is inherent with being Black. He carefully avoids talking directly about Jamaica, his own country, that sees violence and murder on a daily basis, but rather his story of Survival speaks for the whole world in the late 1970s. The apartheid era which never ceases to tarnish the image of an Africa that is beginning to heal from the wounds of decolonization. Following Angola and Mozambique, Marley tirelessly sends support to Zimbabwe and South Africa, whose liberation seems to never see the light. In July 1979, the Wailers headline the Amandla Concert at Boston’s Harvard University (along with Pattie LaBelle, Eddie Palmieri and Babatunde Olatunji). The funds raised from the concert are intended to give support the anti-apartheid struggle. On stage, he declares, “one day soon the whole of Africa will be free!” A few months later, in October 1979, Survival became the first record to feature flags of newly independent countries still unknown to North American audiences, with an explanatory poster as a bonus.

« Africans are liberated, Zimbabwe »

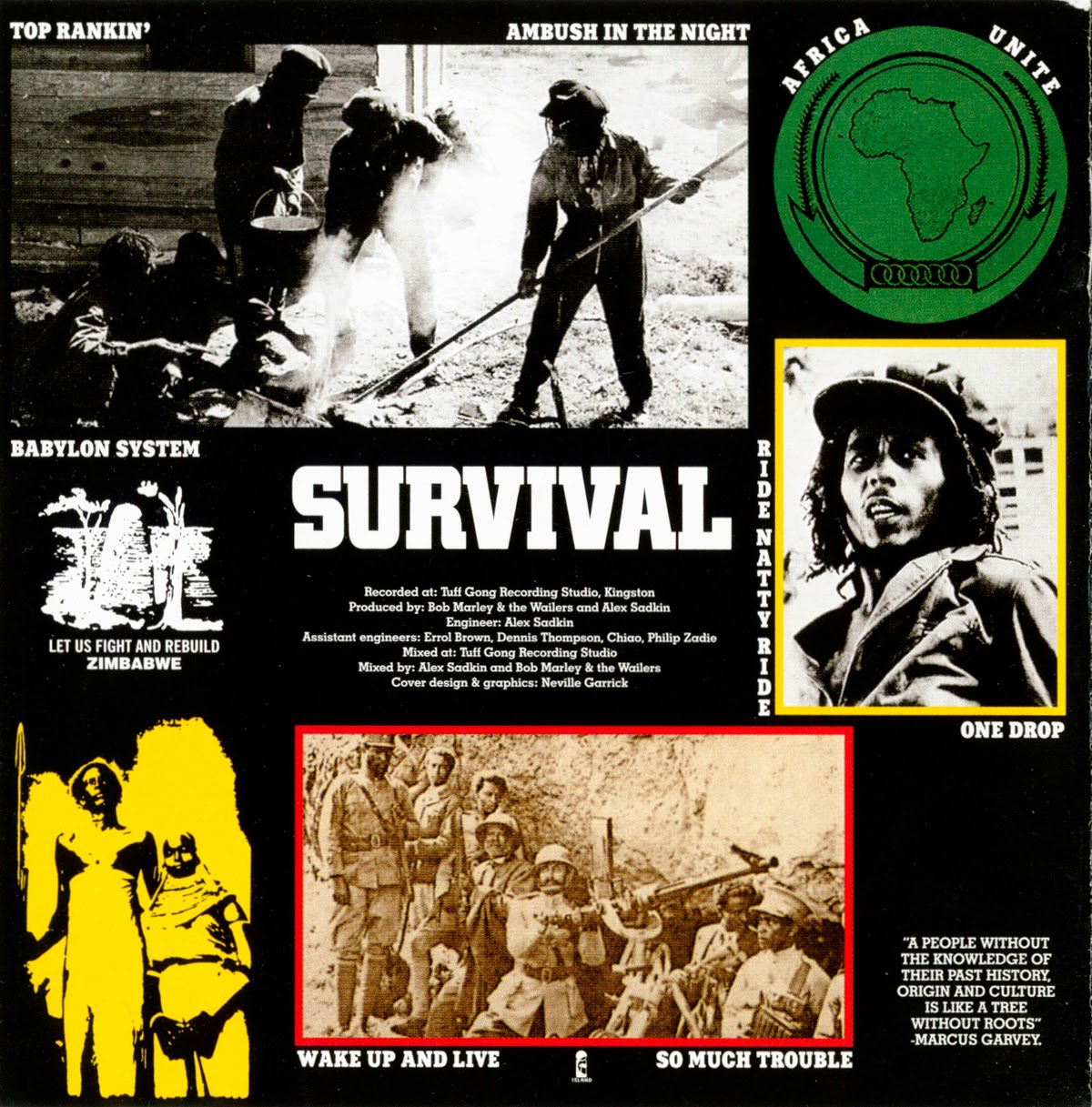

“Bob used to come up with the titles for the albums, but I would always suggest that he used a strong word like ‘Survival’, ‘Uprising’, ‘Confrontation’,” says Neville Garrick, the designer of Marley’s most famous front covers. “Survival was a very political album. I was immediately drawn to the new African flags and their green-yellow-red colors. I didn’t know all the countries, so I contacted the United Nations to make sure I wouldn’t forget any! Of course, I didn’t include the apartheid-run South Africa. And then I also included shots of the holds of the slave ships where the slaves were crammed into. This drawing was supposed to represent the Black diaspora outside of Africa, otherwise I would have had to wonder if I should include a flag of Jamaica or of the United States! My issue was that Zimbabwe was still called Rhodesia and had a colonial flag. I finally included the flags of the two parties fighting for the country’s independence, ZANU and ZAPU.” The record also features the famous song “Zimbabwe”.

On April 17, 1980, Marley sang the song in Salisbury (now Harare) to celebrate the independence of former Rhodesia, and invested tens of thousands of dollars to organize a concert in this country which had never experienced an event of such magnitude. The track, released just a few months earlier on Survival, was composed a few years prior during the singer’s first trip to Ethiopia. When Marley arrived on stage, the track had already become the anthem for the “freedom fighters”.

Zimbabwe’s new flag is hoisted in front of Prime Minister Robert Mugabe (who has yet to unleash his reign of terror), Indira Gandhi and Prince Charles. “Back then we didn’t really understand what was going on,” says guitarist Junior Marvin. “Very quickly you could smell tear gas, and the police suddenly intervened, and we were forced to leave the scene. Everything was very tense. However, it was just people who wanted to come into the stadium to hear us play ‘Zimbabwe’!” After everything turned quiet, the Wailers took to the stage again. The Salisbury stadium then became a symbol for the struggle of Black people in Zimbabwe, in the same way the Zairian stadium made its country famous by hosting the Foreman-Ali fight in 1974. Bob Marley sees his dream come true but he is affected by the turn taken by the concert. The band will play in front of another 100,000 people the next day. “I had heard about Africa, read books, but it is thanks to Bob’s music that I really experienced this ‘survival’, this fight,” said American guitarist Al Anderson. “In Zimbabwe, we became the figures of independence. I remember the new flag being hoisted, it was very moving. I had never seen so many people celebrate a victory in the fight against Babylon.”

“Dready got a job to do / And he’s got to fulfill that mission” prophesied Marley in “Ride Natty Ride”, another track from Survival, as if to emphasize that he now knows he has a role that goes beyond the boundaries of show business. “But we will survive in this world of competition” he continues in the song which, much like the whole album, interweaves recent personal experiences: in this case, the assassination attempt; the Rastafari cosmogony (“Babylon System”) and the great battles of the late ’70s, in particular those of Africa and its diaspora that continue to fight for more freedom throughout the world (“Zimbabwe”, “Africa Unite”, “One Drop”). Bob Marley leans heavily on Biblical references, speaking of the cornerstone, ceaselessly neglected by its builder, as well as the vengeful divine fire of the prophet Ezekiel as an expression of an apocalyptic vision by which the Almighty takes back his rights and punishes through destruction. Marley speaks much of Africa but also wants to reach the Black American audience: the release of the album is justly celebrated in Harlem, at the famous Apollo Club on 125th Street, a hub for Black American culture that cemented the careers of Billie Holiday, James Brown, Michael Jackson and Lauryn Hill. And even if, back then, The New York Times judges the singer as going soft, the audience that allows him to dream welcomes him back triumphally, as Marley sings to them: “We’re the survivors, yes: the Black survivors.”