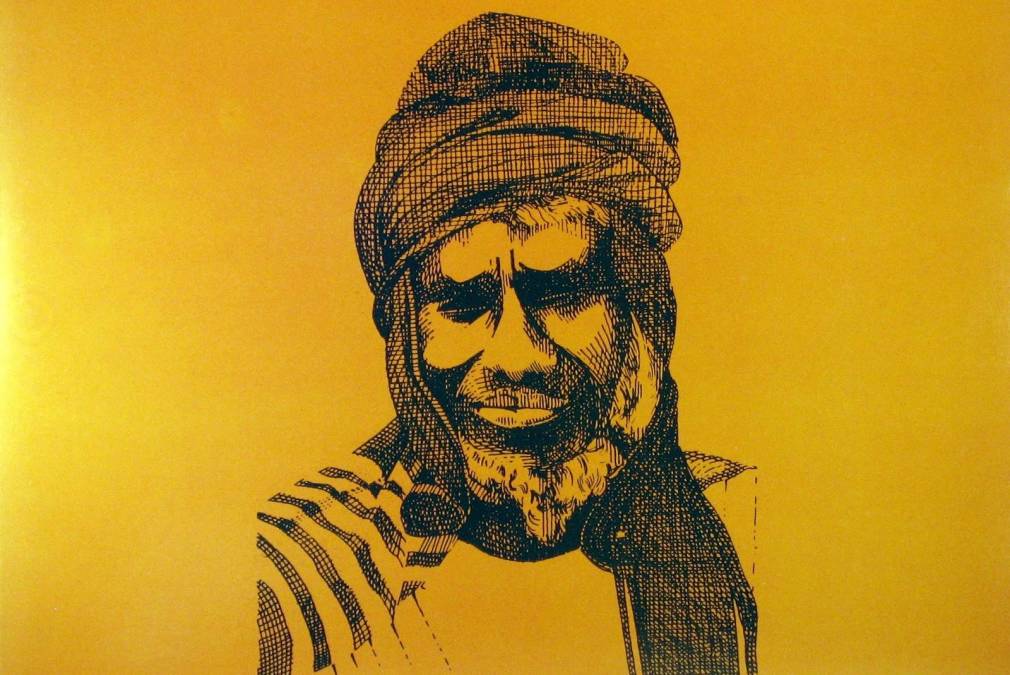

On October 2, 1958, Guinea became independent. Ten years later, the country paid tribute to the towering figure of Samory Touré, a hero of the anti-colonial struggle, in a masterful work, crafted by the Bembeya Jazz National.

Today Guinea celebrates the 62nd anniversary of its independence. An opportunity for PAM to revisit the amazing Regard sur le passé (“Looking back at the past”), which tells the story of Samory Touré; the last great West African resistance fighter against French colonial invasion. Only Bembeya Jazz could put such a story into music, in the great griot tradition. The album; published in 1969, would go on to inspire many more orchestras including Rail Band, Super Mama Djombo and many more.

The history of this record begins in September 1968, with the anniversary of the country’s independence on the horizon.

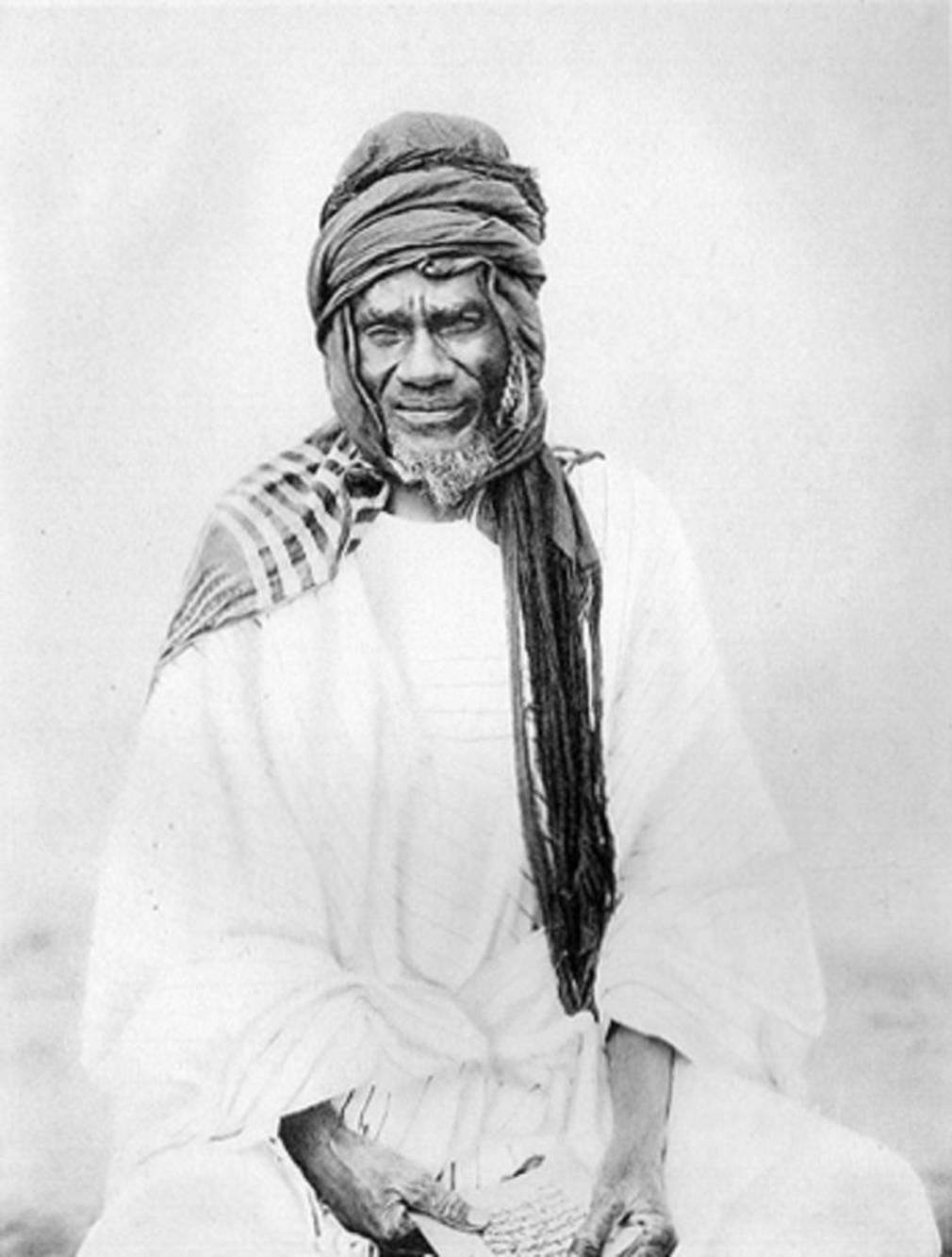

Sékou Touré; the Guinean president, arranged with Gabon the repatriation of the body of the Emperor of Wassoulou, who had long resisted the French colonial troops. Eventually captured in 1898, Samory was deported to a Gabonese island and would die there on June 2, 1900, following a battle with pneumonia. The remains of the one whom Sékou Touré made a national hero returned to Guinea, just like those of Alpha Yaya Diallo (another resistance fighter, King of Labé, deported and died in Mauritania). The Guinean president, who invested massively – in the name of the State – in culture and in particular in orchestras, launched a national “tribute song” competition, which was intended as “a tribute to the heroes and their fight against the colonial invaders.”

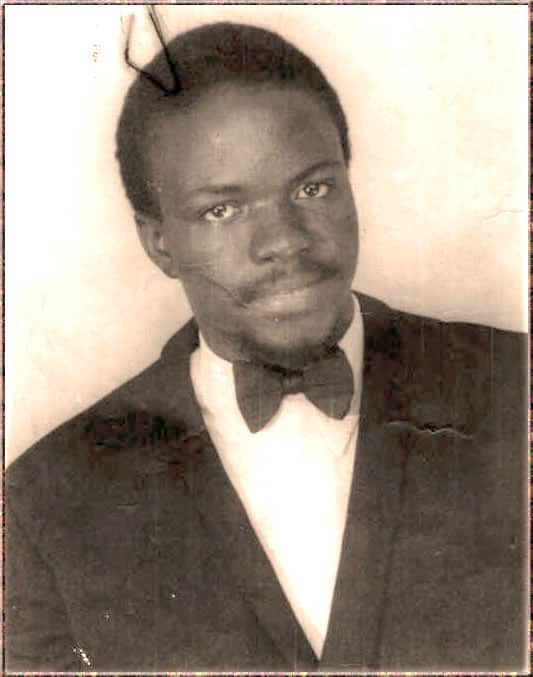

The Bembeya Jazz; appointed as national orchestra three years earlier, took on the challenge. The extensive rehearsals were attended by the president himself, in the company of Aboubacar Kanté; boss of the State-run label Syliphone. A few griots; masters of tradition, were consulted as well as ideologists of the (singular) party, because Regard sur le passé, Bembeya Jazz’s masterpiece, had to also serve the causes current to the regime. Finally, on October 2 (Independence Day), the Bembeya orchestra performed the track for the first time at Conakry’s People’s Palace. As Justin Morel Jr. and Souleymane Keita recount in the book they wrote about the orchestra*, star singer Aboubacar Demba Camara appeared on stage dressed in the attire worn by Samory Touré’s sofas (cavalrymen).

This epic poem put to music made its impresion. It begins with a long melodic descent on the balafon and then mirrored on the guitar by Sékou “Diamond Fingers” Diabaté. A sonic illustration of modernity rooted in tradition, or better yet, as Sékou Touré put it, “proof of authenticity”. The rest of the orchestra then swings into action and sets the stage for Demba Camara’s crisp vocals.

Sékou “Le Growl” Camara takes a hold of the lead vocals in French and tells us the story:

“The melody you hear is a composition in honor of the Emperor of Wassoulou, Almamy Samory Touré, whose anti-colonialist struggle gave birth to Africa’s finest chansons de geste [songs of heroic deeds].

Listen! Listen, sons of Africa! Listen, women of Africa! Listen, too, young people of Africa — tomorrow’s hope, will become a page from a glorious African history.”

Thus this epic poem, which is sung in Malinke, with its spoken parts recited in French, was understood by all Guineans, and well beyond the borders of the country. Composed of storytelling parts, chants and grand instrumental voyages; the song is a true musical legend, beyond the story it tells.

The Bembeya came first in the national song competition and following some edits requested by Sékou Touré himself, went on to record the album Regard sur le passé. The 17th take (the bands used to record live without any break) turned out to be the right one. A piece of history was cut onto wax forever, divided into two parts, one for each side of the 33 rpm disc.

Bembeya Jazz also performed the song a few months later, at Algiers’ Pan-African Festival where they would win the silver medal. Most importantly however, is that this ambitious endeavor set the bar high for African music and would then go on to inspire hundreds of artists to come from West Africa.

“There are men who, although physically absent, continue and will continue to live eternally in the hearts of their fellow men. Colonialism, in order to justify its domination, portrayed them as bloodthirsty and savage kings. But, crossing the dawn of time, their story has come down to us in all its glory.”

The ending of this story is a sad and portentous one, owed to the treachery of French colonial troops and the capture of Samory; his place of exile and his death alongside his faithful companion Mory Tidiane Diabaté.Regard sur le passé aimed to provide an updated – African take – on the continent’s history, through the illuminative life experiences of one of its great leaders. The challenge; after more than a century of colonialism, was to restore pride in Guineans so as to allow them to forge their own history and heritage.

“On September 29, 1958, the Revolution triumphed, avenging us definitively on another September 29th, this time in 1898; the date of the arrest of the Emperor of Wassoulou, the almamy Samory Touré.”

Regard sur le passé was therefore a way of strengthening the legitimacy of Sekou Touré, continuing the work of Samory’s. Nevertheless, the leader of the Revolution, a fervent Pan-Africanist, eventually became a tyrant within his own country. And the arts; once a means of emancipation, became a privileged tool for his own propaganda and that of his party: the PDG (Democratic Party of Guinea). A few months later in 1971, the Bembeya Jazz took things further with the lengthy “Chemin du P.D.G.” (“The PDG’s path”).

Becoming obsessed with the conspiracies; Sékou Touré sent many of his opponents – real ones or alleged – to die in the cells of the Boiro camp. Emile Condé, one of the very first promoters of Bembeya Jazz (then the “Beyla Orchestra”) was taken there in 1971 before like so many others; being assassinated. Just like Fodeba Keita, founder of African Ballet and first Minister of Culture for independent Guinea. The Revolution had given birth to magnificent music, but little by little it also began to devour its own young. And no one has yet come to sing their requiem.