An introduction to the collective that is shining a spotlight on buried Eritrean masterpieces, online and in-person, for a celebration of culture and heritage.

Sometimes the Instagram algorithms get it right and suggest musical treasures that are right up your street. Eritrean Anthology knocked me out with playlists of gems transporting me back to a time I didn’t live but have somehow inherited a visceral memory of. Hypnotic tunes, pulsing persistent and repetitive in the best way. Melodies that slink up and into ears through your shoulders and neck. Unearthed, searing laments; moaning, funky and suspenseful horn sections and rippling guitar licks. Is that an Eritrean James Brown? Do I hear a touch of Cuban coro? This was giving my diaspora ears an Eritrean music education that had evaded me. The records my father played in 1960s Addis DJ sets were mostly American, all the rage with Habesha hipsters, especially those who came of age within earshot of Kagnew station’s airwaves.The American bass sparked the emergence of the Asmara jazz scene, some of which was immortalized on wax. I don’t recall exactly when I discovered this wonderful resource of vintage Eritrean tunes but I remember immediately sharing it with my friend Nahom, who, as it turned out, was the man behind it.

Nahom’s earliest music memory is a 1980s analog cassette tape of Eritrean revolutionary music artist Wedi Tukul. The raw sound of the revolutionary music, recorded through a microphone, not in a major studio, with backing singers providing the rhythm with their clapping. “I couldn’t tell you what he was saying now, but really, you could feel what he was saying. That’s my earliest memory of Eritrean music.”

Some legendary live performances made an indelible impression on him: Abraham Afwerki, Abebe Haile, with a post-independence all-woman line up, and even the great Tsehaytu Beraki whose Medjemerya Fikri is a colossal classic, a monument. Powerful music that soundtracked the struggle, that galvanized people to join the fight for freedom.

The momentum for Eritrean Anthology gathered over years. An invitation by a mutual friend, Elelta, years ago, to her podcast, to talk ‘60s and ‘70s Eritrean music sparked a wider online conversation and curiosity, even prompting Nahom to attempt contacting Tewelde Redda, one of his musical heroes. It didn’t work out and the project quietly faded away, shelved until last year.

Lockdown gave us all more time to think and Nahom thought of ways to combine his interests. Lwam and other friends reminded him what he was all about. Eritrean Anthology was born out of his passion for the music, his love for the country, identity, and culture. Eritrean Anthology is built on the desire to bring all of these things together into a space that could contain all of our stories, into a place where different generations could learn and reconnect over songs nearly forgotten. The A-side: introducing the music to new ears and music lovers, this glorious, overlooked, Eritrean music history. The B-side: sharing and spotlighting, community response, getting young people to ask their parents what this music meant and means to them.

Eritrean Anthology unearths buried musical masterpieces to us via social media and these international collaborations. Nahom reached out to Amsterdam-based artist Bahghi to celebrate Tsehaytu Beraki’s 80th birthday through covers and original compositions.Together they mapped it out and made it happen. Followers flocked to the page, and by the time of Eritrean Anthology’s first birthday, marked with a set on Kindred radio, they were nearly 2000 strong. More recently, Eritrean Anthology teamed up with Lemlem Eritrean kitchen to provide a simultaneously old-school and modern surround sound, savory experience. Nahom went head-to-head with friends from Laidback Fracas for online DJ sessions and explorations. He invited DJs from Japan, New Zealand and beyond to weigh in on their favourite Eritrean records as well, some such fans that they had even gone to Eritrea to meet their favourite musicians.

Eritrean music is largely overshadowed by music from neighboring countries like Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia, but Eritrean Anthology united fans around the world.

Three Eritrean Anthology favorites

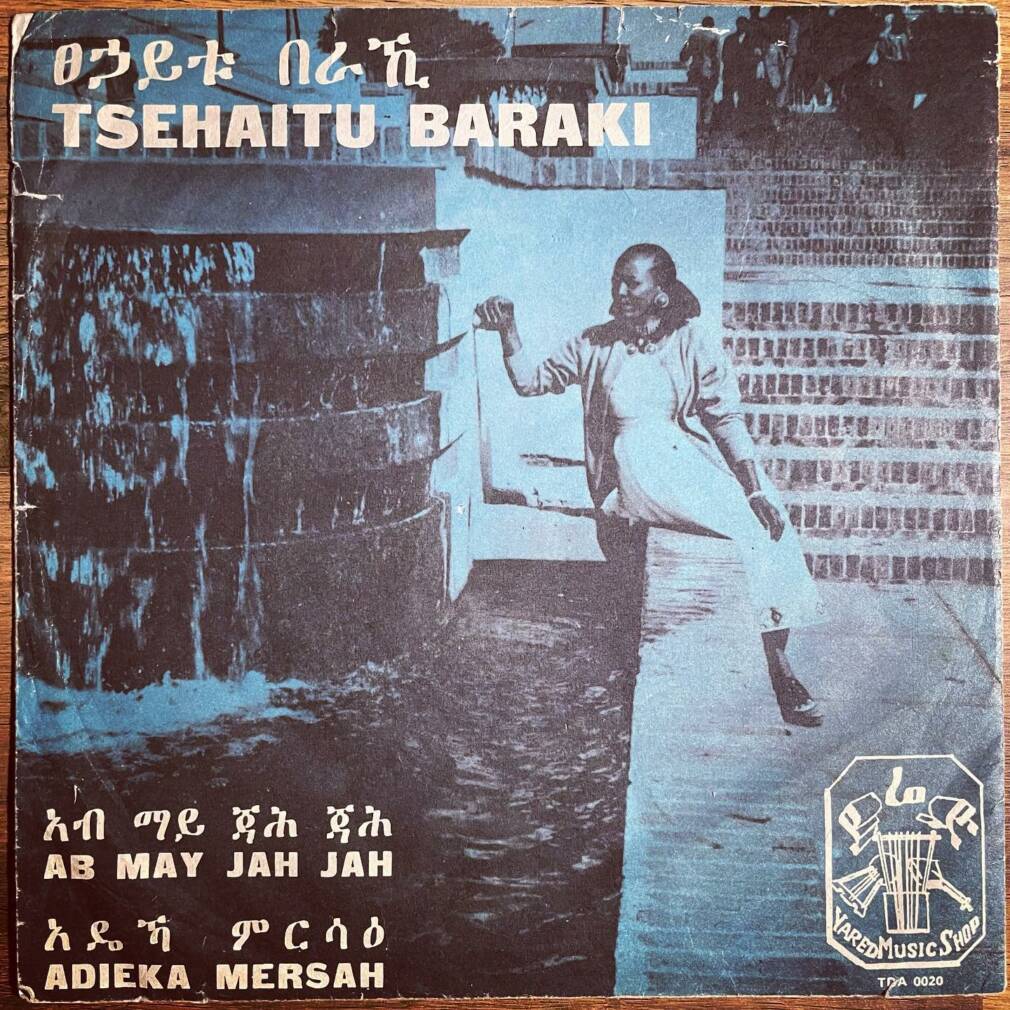

Tsehaytu Berakhi and Tewolde Redda’s final collaboration released on Redda’s Yared Records.

Record: Ab May Jah Jah / Adieka Mersah

Performed by: Tsehaytu Beraki

Arranged by: Tewolde Redda

Label: Yared Records, TDA-0020

Year: 1973

Emporio Musicale’s first release is this beautiful record by Haile Ghebru & Zerai Deres Band.

Record: Halhalta Ficrichi / Haderachi

Artist: Haile Ghebru & Zerai Deres Band

Label: Emporio Musicale, ER-1 & 2

Year: Unknown

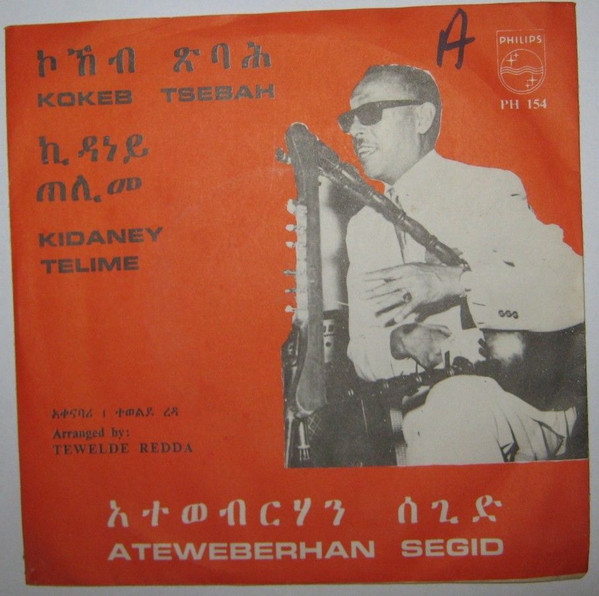

Record: Ab May Jah Jah / Adieka Mersah

Artist & Composer: Ato Ateweberhan Seghid

Arranger: Tewolde Redda

Label: Philips PH-154

Year: 1972-73 (Estimated)

In Nahom’s own words

“For me, what’s more interesting is how we can build on the relationship with our country, our friends, and our family through a different topic, perhaps, a topic that’s less discussed. Eritrean arts and music. I think Eritrean music nowadays is a lot more accessible because you’ve got YouTube, you’ve got mainstream media, you’ve got different types of mediums that are more accessible, digital music, for example. So today Eritrean music is more accessible than perhaps this particular pocket or era of music that we focus on at Eritrean Anthology, which has largely been overlooked.

It’s been 50 years now since these records were released, but also, I feel like that’s the space that I wanted to perhaps shine some light on because of its rarity/obscurity and it enables us to have a conversation with our parents, with our loved ones who may have had those kind of personal experiences and relationships with those records and gives us an opportunity to have these conversations that we never had before.

One listener mentioned that Eritrean Anthology sparked one of the best car conversations she’s ever had with her parents. Personally, I’ve had those moments as well with my mother, my aunt, and my uncles. We’ve been discussing this for quite some time now and I’ve been able to learn things that I haven’t learnt before. My mom used to go to afterschool theaters and clubs, where she heard this kind of music in a live format. Live bands would play and the entire school would dance to it. Those are the kind of stories that I’m now getting from my mom that I never used to get before this project. I really encourage anyone to do the same, if they haven’t already, to just have that kind of conversation, because this could be our seat at a table we’ve never had before. That’s really what I’m trying to achieve with this. The music is just a means to the end, really.”

That’s what the love and passion of music does to you. Sometimes it takes you to places that you never thought you could go.

Sometimes it takes you home.