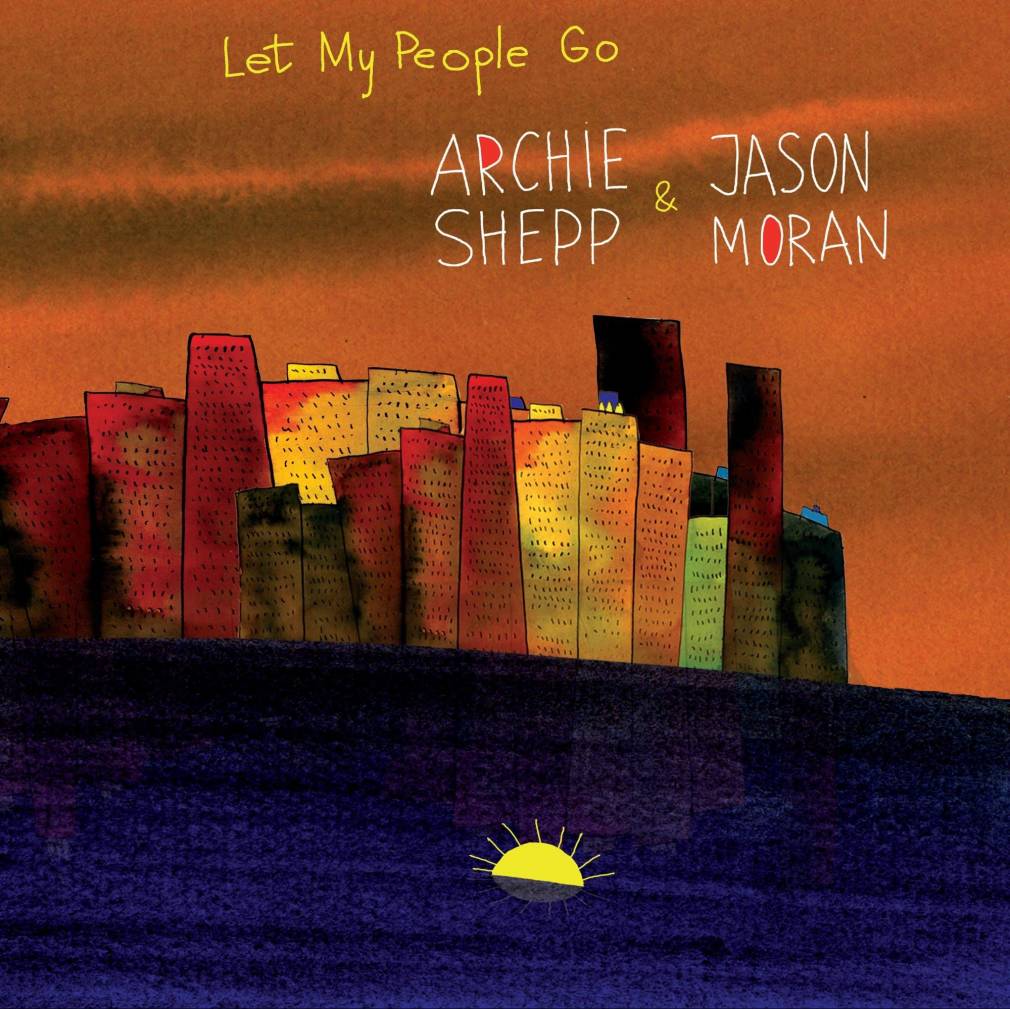

Let My People Go: a truly symbolic title… It is the refrain from the most famous Negro spiritual, “Go Down Moses”, dating from the days of slavery, and in 1853 it was the first one to be edited as sheet music, ten years before Abolition in the United States. Massively evangelized in the 19th century, the African slaves quickly identified with the Hebrews who, according to the biblical legends they were taught, had rebelled thanks to their faith and had fled from Egypt where they had been enslaved. Other ancient spirituals are more like laments, such as

“Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” (another song on the album), but in a condition of servitude a lament is not far from a revolt.

These two songs became world-famous in the 1920’s, thanks to the great singer/actor Paul Robeson, a champion of the civil rights struggle, and then later to the phenomenal success of the magnificent 1958 album by Louis Armstrong, “Louis and The Good Book.” I was six years old, it was a Christmas present, my very first “jazz” album… When Shepp sings these spirituals so sorrowfully with his rusty old baritone voice, he seems to be assuming the role of the ideal successor to Robeson and Armstrong. But it is obviously not so simple…

Back to the roots of jazz, in search of new things

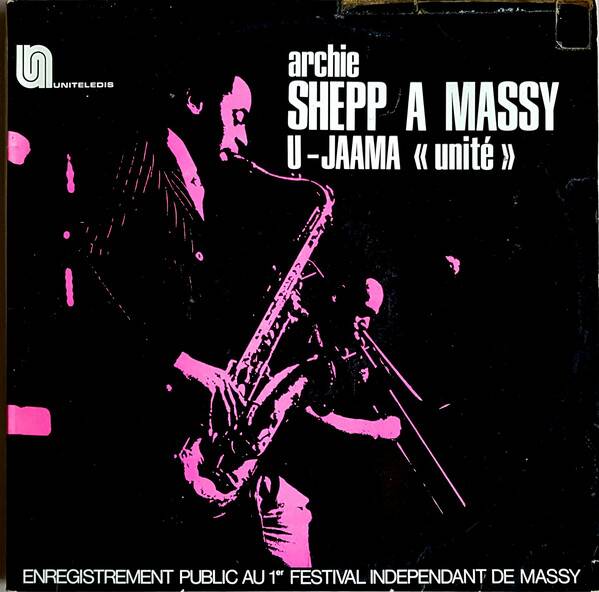

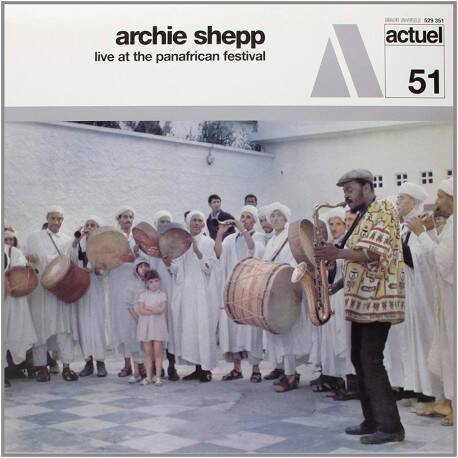

My first encounter with Mister Shepp was unforgettable. It was in the fall of 1975 at the Fnac-Châtelet (a large record store in Paris), where I was a sales clerk in the jazz section. I didn’t immediately recognize, from behind, this tall, imposing, elegant and somewhat stiff man who was busily searching through the bins. Photos taken at the Pan-African Festival in Algiers in 1969, where he had been the unofficial music embassador of the Black Panthers, companion of Eldridge Cleaver and Stokely Carmichael, showed him in magazines wearing a djellaba and an embroidered bonnet… And here he was in Paris dressed in traditional hat-suit-tie attire (and which he continues to wear to this day). Archie was looking – for the record library of the University of Massachussetts where he was teaching – for an extraordinary document on the prehistory of jazz: the hilarious interview of Jelly Roll Morton by Alan Lomax. The pioneering genius from New Orleans, sitting at his piano, explains for nine hours how he “invented jass”. Impossible to find in the USA, I had a rare English edition of the LP box set in stock… I was quite proud to offer it to Archie. And so our first encounter was made through our shared passion for the sources of “jazz”. To thank me, Archie gave me an invitation to his concert at the Massy Jazz Festival.

And this is how I saw Shepp on stage for the first time. What a shock! We were all stunned, the way our parents had been when they had witnessed Dizzy Gillespie’s Big Band in concert. Propelled by the frenetic drumming of Beaver Harris, Shepp played like a man possessed, but with a mastery of the tenor sax worthy of his revered ancestors: Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young and especially Ben Webster. This concert became legendary, issued as an album under the title U-Jamaa. This Swahili word (“extended family”) symbolized the socialist version of Pan-Africanism at the time. It is one of Shepp’s most famous compositions, a joyful song that was long his signature tune. The day the Pan-African project finally comes true, it could be an ideal anthem for the United States of Africa.

The other masterpiece of this album is Beaver Harris’s impressive “African Drum Suite”. Ever since the 1960’s, many of Shepp’s works have explicitly evoked Africa: “Le Matin des Noirs” (The Morning of the Blacks), “Kwanza”, “Song For Mozambique”… One only needs to listen to the magnificent

The Magic of Ju-Ju (1968) to understand the crucial influence Shepp’s expressive playing had on Fela, who was on tour in America when the album was released. Both were in contact with the Black Panthers at the time. After Fela’s death, Tony Allen invited Shepp to play on the superb collective homage Red+Hot+Riot, where he plays with Ray Lema, Baaba Maal and Positive Black Soul. Since then he has often been invited by Fela’s son, Seun Kuti, to perform as a soloist with the family orchestra Egypt 80.

In the wonderful documentary made about him by Frank Cassenti, Je suis jazz…c’est ma vie (I Am Jazz, it’s My Life), Shepp already expressed himself in French (since that Massy concert he has often stayed in France, and now lives in the Paris suburb Ivry-sur-Seine), and he thus summarized his approach:

“Every time, with my musicians I try to find something new, I approach my music with a spiritual and intellectual concept that has its origins in Africa, I believe, and it continues through people in the United States. That’s the music that you call ‘jazz’. For me, it’s my classical music. Charlie Parker is my Bach. Coltrane is my Beethoven.”

With Coltrane, on the way to Africa

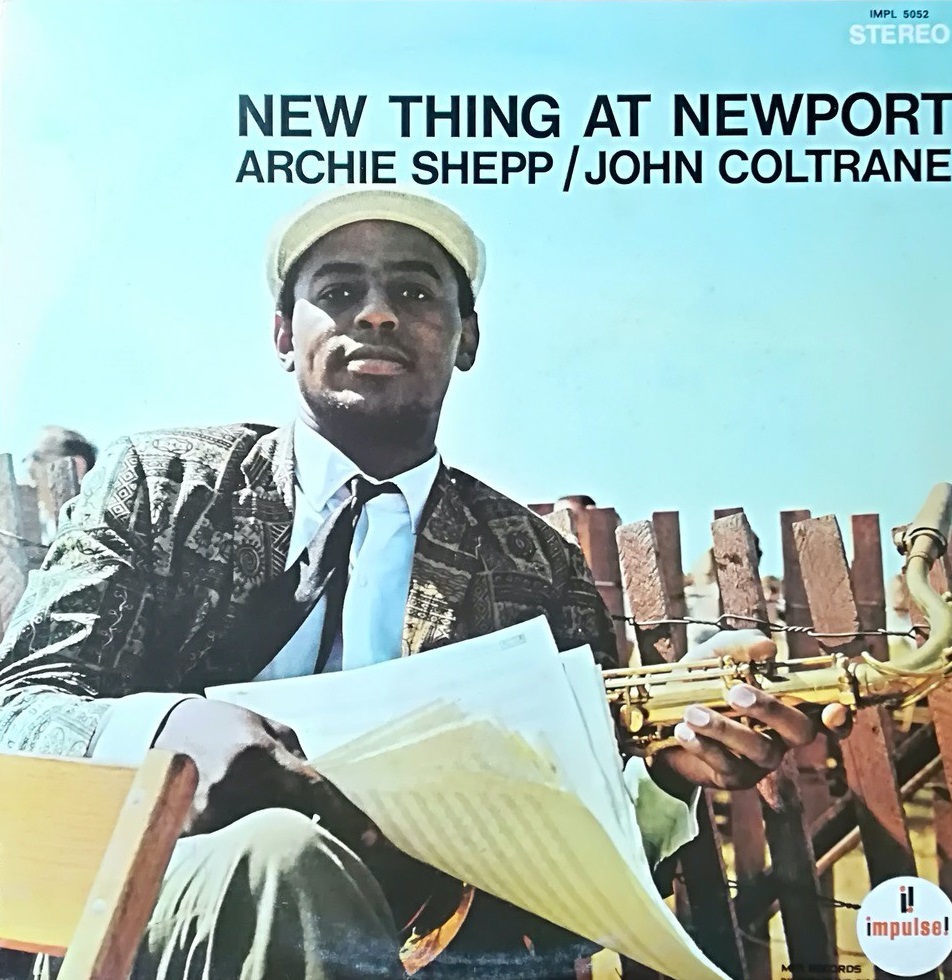

There is no question that his Pan-African tropism is a heritage from John Coltrane. Even if it is the pianist Cecil Taylor who convinced the young Archie – who at the time was passionate about history and literature, a budding poet and playwright – to concentrate completely on music, he has always been (along with Pharoah Sanders) the disciple closest to John Coltrane, who in 1964 took him under his wing and helped him to be signed to his record label Impulse. Coltrane adopted Shepp like a younger brother. He hired him to play on his album Ascension and on the first version of A Love Supreme.

Even better, he helped get him a gig at the Newport Festival; for Shepp it was a consecration. Impulse released the impressive live album New Thing At Newport, with Coltrane’s quartet on side A and Shepp’s quartet on side B. The term “new thing” was adopted by the new generation to designate “free jazz” without using the word “jazz”, which they judged too tainted by the exoticism and “uncle-tomism” dear to “white” music lovers…

Their music itself rejected the harmonic and tonal rules still followed by the legendary improvisers of bebop, the modern jazz of the 1940s-1950s. They also refused to copy the new aesthetic promoted by the European composers of the first half of the 20th century, Schoenberg, Berg, Milhaud, Stravinsky, Milhaud, Varèse… Archie Shepp expressed this break in clear terms: “As soon as my own dreams were sufficient, I glossed over the entire Western musical tradition.”

Shepp was also one of the first to reject the word “jazz” for “Great Black Music”… Indeed, it was the musicians of his generation who most contributed to the media and the public eventually dropping the old racialistic adjectives “Negro”, “Colored”, “Black”, “Indigo”, “Tan” etc., for “Afro-American” and then “African-American»…

Eternally grateful to his elder, Archie Shepp entitled his first studio album as a leader Four For Trane. Coltrane supervised the recording, and a sign of their intimacy is the way Shepp played with a fascinating freedom works that John had dedicated to those close to him, “Cousin Mary” and the sublime “Naima” (the name of Coltrane’s first wife)…

Coltrane’s repertoire abounds in African themes: “Dakar”, “Tanganika Strut”, “Dial Africa”, “Gold Coast”, “Dahomey Dance”, “Tunji”. This last title is a diminutive of Babatunde Olatunji, the Nigerian percussionnist who emigrated to New York in 1950, and the founder, in 1965, of the Center for African Culture that was highly frequented by avant-garde jazzmen. Coltrane, already gravely ill, gave his two final concerts there, on April 23, 1967. He had asked his friend “Tunji” to organize his first voyage to Africa. Alas, Trane died three months later without ever realizing his dream. It was Sanders and Shepp who took up the torch.

Archie in an extension of John’s work in every aspect. The key words in his art are always the same: Africa, Blues, Eloquence, Freedom, Lyricism, Sensuality, Spirituality…

One of the key tracks on the new album, once again, is a Coltrane composition: “Wise One” (The Sage). This word seems to apply as much to Archie Shepp’s mystique, who has always claimed to be a “Marxist”, as to John Coltrane’s. Indeed, Shepp has never disavowed his third-world engagement of the 1960’s, nor his long-standing proximity to his friend the immense writer, cultural activist, critic, playwright and poet Leroi Jones (who later changed his name to Amiri Baraka), who was the leading thinker behind the Black Panthers,, and who wrote in the liner notes for the cd reissue of Shepp’s album Four For Trane:

“Shepp immediately appeared in the front rank of post-Coltranian tenors… but he only plays his own role, in the same way that all those from his generation who learned from Ornette Coleman and from Cecil Taylor how to express the deepest sources of emotion, and who have been able to sing a song that was truly their own.”

It should be added that Archie has never stopped evolving. If musicians like Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins progressed through stops and starts, through hesitations, breakthroughs, disappearances and resurrections, Shepp has always seemed to be rock solid. He has an elegant and athletic way of navigating between periods and styles. I admired the ease and the pleasure with which he recently collaborated with the rap pioneer Chuck D (of Public Enemy) and then with the rapper/beatboxer Napoleon Maddox…

But there is nothing surprising about his eclecticism and his musical agility. Like Ornette Coleman, Pharoah Sanders and most of the pioneers of the “free jazz” generation, Archie learned to play in the dance orchestras of the 1950’s: the mandatory mambo and rhythm’n’blues grooves of the time.

There is always, at the core of his of his toweringly expressive playing, the necessary, profound and fertile experience of popular music, of seduction incarnate. Shepp is a living musical, emotional, erudite, intelligent, and passionate memory of all African-American people, as well as of all people of African descent.

The art of the duo, from one generation to the other

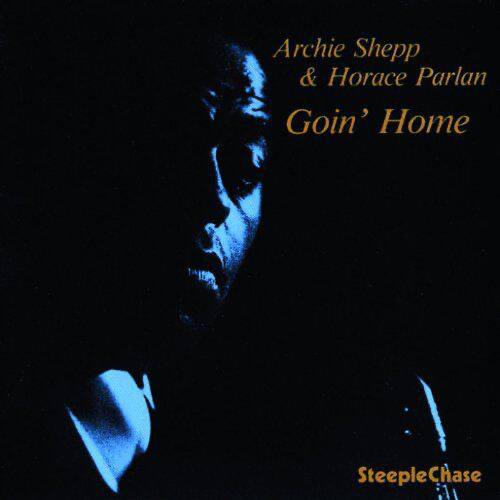

On this new album, Shepp is once again in a duo setting. A format he adores, ever since the unforgettable albums Goin’ Home (1977), Trouble in mind (1980) and Duo Reunion (1987) with the lyrical pianist Horace Parlan. These three albums are already the perfect sketches of an absolutely dazzling series. (And there is also the truly sublime duo album with Dollar Brand, Duet, 1982). It would be cruel to compare them with this new opus: Jason Moran is a dazzling piano virtuoso, Horace Parlan was a modest, restrained, introspective pianist. As for Archie, at 83 years old he obviously doesn’t have the same strength and velocity he had at 40. His blowing is weaker, shorter in breath, even if his inimitable sound is intact, at once throaty, rugged and yet so tender and voluptuous. The very same sound, absolutely, that had fascinated and petrified me at the Massy concert so long ago, and that I will always recognize without hesitation out of a million saxophonists.

His fingers are still agile on the soprano sax, a little less so on the tenor… But no matter, what he has lost in technique he has gained in emotion, in spirituality, in subtlety.

And then there is his voice, absolutely unique, which is not a wild card, a substitute for his instrument, but quite simply the opposite. Over time it has become obvious that Shepp is not a saxophonist who sings, but a formidable singer who lends his voice to saxophones, the way others sell their soul to the Devil, or to God, or the gods, who knows!

The touching voice of an old man? No, Shepp, sings like a young man transfixed by the voices of his ancestors. His voice is that of an entire people, and he has always thought this way, ever since his first poems and plays, written before he was even known as a musician. And it is indeed History, his people’s, that his music describes: Shepp has never played nor sang anything else. He belongs to no generation, he is his people, he is the people.

“My people”, wrote Duke Ellington in his autobiography (Music Is My Mistress) “are all peoples”.

Archie Shepp has released some hundred albums since 1960, and on most of them there is at least one Ellington composition. This time, there are two: “Isfahan”, an unusual Persian melody, composed while on a tour of the Orient. Ellington was a precursor of “world music”, Shepp knows it, and reminds us with a profound fervour for the ancestor, the Duke. This is the track where Shepp seems to me to play at his best (sorry, I’m not a sports journalist). The other Ellington composition, the next track on the album, is “Lush Life”, the masterpiece by Ellington’s alter ego, Billy Strayhorn, and here Jason Mason seems to have the advantage (sorry, I’m not a sports journalist), but Shepp quickly catches up with a wonderful coda sung with his crepuscular voice.

One of the summits of the album is the final track, an overwhelming version of Thelonious Monk’s masterpiece, “Round Midnight”. The old sage Archie never ceases to amaze us. The ancestor here dialogues on equal footing with a pianist who could be his grandson (four decades younger)…

Indeed, Jason Moran belongs to a generation that never experienced the fury of “free-jazz/black power”, the bloody riots in Black prisons immortalized by Shepp on his harrowing album “Attica Blues”, the huge demonstations for equality that were violently broken up by police dogs and truncheons, the concerts where the music was a howl to cover the sounds of police sirens… No matter, they are on the same musical wave-length, through the vast musical heritage of the South where they both come from. Jason is Texan, Archie was born in Florida, even if he grew up in Philadelphia. Jason was a student of the legendary Jaki Byard, the best pianist to feature in Charlie Mingus’s band after Bud Powell. Byard’s playing, like his teaching, covered the entire history of African-American piano music, from ragtime to free. In fact, Jason dedicated his first album to Fats Waller, which is quite something for a pianist who was born at the same time as the arrival of rap music, in 1975!

And this is what, in my opinion, is the secret of the great beauty of Let my People Go: the profoundly successful oral transmission across generations, encompassing the entire African-American musical heritage. It takes place within families, in the schools and churches of the ghettos, but especially on the job, in the jazz clubs where generations as well as ethnic origins interact harmoniously. The continuity of this musical history – from the founding spirituals to blues, jazz, RnB, soul, funk and rap – could and should serve as a model in Africa, where unfortunately nothing is being done for music to be perpetuated across generations, and where even traditional African musical instruments are now disappearing.

Let My Pepople Go out now.