As is often the case in Africa, the name is the first mark of identity on a newborn child. It may recall an event that occurred in the year of birth, indicate a distinctive sign, or surround the newborn with wishes and blessings intended to accompany him throughout his life on earth. Okwuchuku Osadebe has not escaped this tradition: his name, shortened from a longer formulation, means “may the word of God come true”. His last name Osadebe “may God keep him alive” redoubled these blessings and was made famous by his father, Chief Stephen Osita Osadebe, one of the monuments of the Nigerian highlife, to which he knew to insufflate elements resulting from the Igbo traditions which will make its success. It is from him, without question, that his sons – including Okwuchuku known as “Okwy” – have inherited.

“Dr of Hypertension”

The man, born in 1936 in southern Nigeria, was named “Doctor of Hypertension” after the healing vibrations that emanated from his music. He started out in his native village of Atani in southern Nigeria and continued his education at Onitsha High School before moving to Lagos to pursue his musical career. Much to the chagrin of his parents, of course.

“At that time, if you told your parents you wanted to become a musician, they would be like, What?! Who makes a living out of music? Nobody they know. It was like ruining your father’s belief in you.” says Okwy, who was contacted by phone in Connecticut, United States, where he lives.

But Osita Osadebe persevered: in Lagos, he played with EC Arinze and Victor Uwaifo in the Empire Rhythm Orchestra, then later with the trumpeter Zeal Onya. All these artists who became legends of the Lagos night which, at the time, had countless clubs. He was not only a good singer, but also an excellent composer and arranger who earned the respect of his peers who nominated him to receive a scholarship to study in the USSR in order to learn about trade unions and to contribute to the structuring of a musicians’ union in Nigeria. He did this upon his return to Nigeria in the early 1960s.

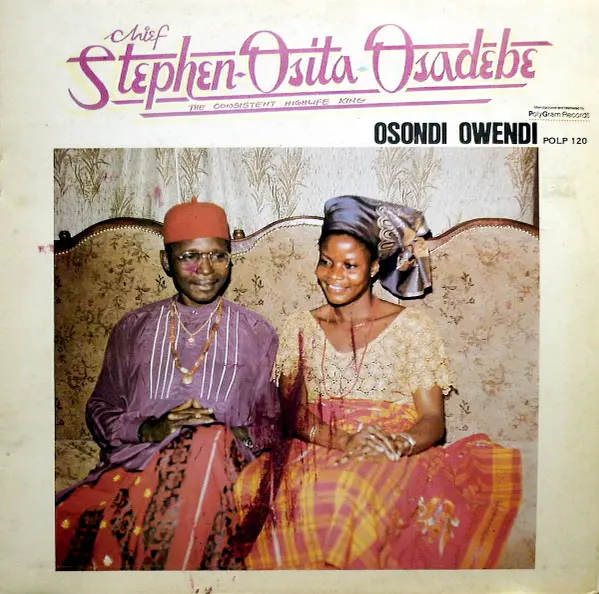

While continuing his collaborations with the orchestras mentioned above, not forgetting Stephen Amache’s Central Dance Band, he finally earned enough money to buy his own instruments, an essential step in having his own orchestra, and founded his own group, the Sound Makers. It is then that he deployed all his creative genius, and composed an incredible number of songs; at least 500 are said to have been written, half of which are recorded on albums published at a rate of four per year. The Biafran War (1967-1970), which hit his home region hard, also marked the end of the domination of highlife in Lagos, which was soon supplanted by juju music and afrobeat. This did not discourage Osita, who continued to tour and also exported abroad (to England in particular) and penned hits like “Osondi Owendi” in 1984, which remains a classic of modern Nigerian music. His last album, released in 1996, was recorded during one of his tours in the United States, where he finally passed away on May 11, 2007, in Connecticut. It is there that Okwy, one of his sons, lives and would soon take the baton.

Okwy: A legacy to carry on

Like his other brothers and sisters, Okwy grew up in Nigeria where, although he lived in the big city of Onitsha, he went every weekend to the village where his father came from and where his grandfather Obi Osadebe (nicknamed “the chicken feather” because of the lightness of his dance) was waiting to initiate them to the cultures, music and traditional Igbo dances. A heritage that would serve him. Very quickly, his dancing talents were noticed – when his father received friends at home and Okwy started to dance, they threw him bills that his mother, Okwy confides, was quick to pick up.

From the age of eight, he accompanied his father’s shows, joined by his younger sister, first to dance, then to sing. His elder brother opened the act with his singing. The taste for music, and Igbo highlife in particular, runs like blood in the veins of the family. In 2009, two years after the death of his father, Okwy set up his first highlife band in the United States, recruiting talented musicians who were not Nigerians (Nigerian instrumentalists are not common in Connecticut) and released his first EP in 2015.

“I had a legacy to protect. This is my legacy, it runs in my blood, and it’s pulling me steady to get it going. And my father, knowing all he has achieved, if I don’t carry it forward, I feel like I’m disappointing my family, I’m disappointing my father’s spirit and my ancestors. That’s one of the things that is pulling me.”

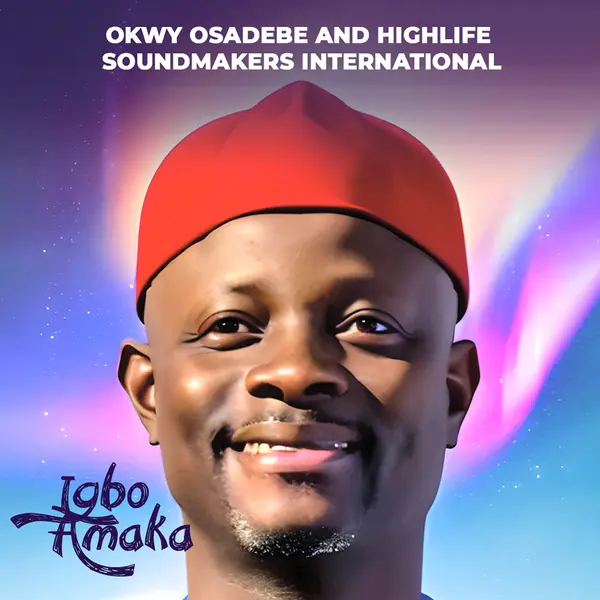

This new album, Igbo Amaka (which could be translated as “Igbo is beautiful”), eight years later, was recorded between Nigeria and the United States, after a number of back and forths. Okwy sent the melodies and rhythms, the musicians in Nigeria responded by playing them, he laid down his vocals, etc…) One could fear that the result would sound flat, but it is not. Okwy presents himself as the faithful heir of his father Osita, from whom he gets his passion for brass and wah-wah pedals, the rhythms and the Igbo choirs that were the signature of Osadebe’s highlife. Like his father, he likes to use village proverbs and make them resonate with current events. Just listen to his song “Dozie Obodo” – or rather watch the video clip, which, thanks to subtitles, gets the message across to a broader audience.

He opens with general passages of popular wisdom like, “don’t wait till someone begs you on bended knee before you do what you are supposed to do“. As the song goes on, this reference, among others, applies especially to the leaders of his country who have become “blind through greed”. And the long litany of the ills of Nigeria is spread out: lack of infrastructure, roads, hospitals … Okwy makes it clear that the elites do not care, since they left to spoil themselves in the West. But when Covid came, the borders closed, and all that was left for them was Nigeria, with its abandoned hospitals. All this sung with the sweetest and most calm voice: one could think it was a love song, but that’s the tone with which Okwy launches his sharp comments.

What he denounces is probably even truer in his native region, which has never truly recovered from the Biafran war. “The entire southeast was devastated: the infrastructure, the economy, millions of lives lost…” says Okwy. “And at the end of this war without winners or losers, the Nigerian government was supposed to rebuild. But it never did. The war was a huge setback for everything in the region, including culture.” This is also one of the challenges of this legacy left by a father to his children. To give back to this region its pride by making its musical genius known. This is what the Colombian label Palenque Records strives to do by searching for heritage and producing those who perpetuate it (like last year’s release of the Oriental Brothers album led by Dan Satch). All these issues Okwy understands well. He knows that Osadebe means “may God keep him alive”. This applies to his family, as well as to the highlife he inherited.

Listen to Igbo Amaka by Okwy Osadebe via Palenque Records and Odogwu Entertainment