Castel Volturno (Italy), 9 November 2008

Just moments after leaving the stage, the singer passes out. She is rushed to the Pineta Grande hospital near Naples, in Southern Italy. Victim of a heart attack, her eyes would no longer open to the world, to its beauty and its inequalities she spent her life fighting against. It was precisely the reason why she went to that small Italian town. She took part in a benefit concert for Roberto Saviano, a local writer hunted down by the Camorra, the sprawling Neapolitan mafia organization he had detailed the influence in the book Gomorra. And this is exactly where Miriam had agreed to play: in the wolf’s den.

Indeed, the diva had not retired from musical yet, any more than she had traded her commitments for quieter days in a country where, after decades of exile, she had finally been able to return. No, Zenzile Makeba Qgwashu Nguvama (her full name) had spent her life fighting, and she died the same way: the words on her lips and a cartridge belt full of songs slung over the shoulder. Her repertoire also bore witness to the pan-African struggles she had taken part in: songs from Guinea, Tanzania, Mozambique… The fights for liberation had their soundtrack, and Makeba was their spokeswoman all over the world. As in the song “A luta continua”, a revolutionary slogan used by the Frelimo (Mozambique Liberation Front).

As she recounts in this concert in 1980 (she participated many times in the North Sea Jazz Festival in the Netherlands), she was part of the Guinean delegation that had came to Mozambique to celebrate the independence of the country in 1975.

She alone embodied the convergence of the pan-African struggles: against segregation in South Africa as well as in the United States; against the colonial presence in Africa; for an African unity… and beyond, for human rights in the whole world. Shortly before her death, she had gone to DRC (Congo), once again, to denounce the sexual violence inflicted upon women. She was an equally inspired mind in the tribune as she was on stage, and she would often put music into politics, and always politics in her music.

Upon hearing of her death, the South Africa, government decreed a day of national mourning. Her body was repatriated, but there’s no use looking for her grave: her ashes were dispersed from the peak of the Cape of Good Hope, just where two oceans meet, so that, as she had confided, the currents would carry them wherever she had set foot during her lifetime.

Become a singer despite the apartheid

The kid who became the muse of Pan-Africanism in songs could have missed out on her own destiny. Flashback on a young Makeba locked behind apartheid’s barbed wire.

Uzenzile: “You can only blame yourself”

If you want to sweep the course of an existence, you have to start from the beginning. The very beginning: birth. The day when African music “empress” – as they would call her later – was born, is a decisive one: indeed, she took her name from that very day.

On March 4th, 1932, Christina Makeba, a professional nurse, feels that the birth contractions are getting closer. Alone at home, she boils water and lays the rush mat on which she lies, and gives birth to a little girl. She cuts herself the cord that connects her to the newborn. The grandmother and the neighbors who heard the cries of the infant come running, only to find the mother lying on the floor. She fainted. The grandmother nods her head and, looking at her daughter, who has just regained consciousness, says: “Uzenzile, you can only blame yourself.” Christina had been told that she and her daughter would not survive the childbirth and, indeed, the thin and sickly girl already showed signs of weakness and could not even eat. As for the mother, she has only become a shadow of her former self. But finally, against all odds, regained their health, and the “Uzenzile” word that the grandmother had let out will remain in the family’s history as a tender reproach, falsely angry. Anyway, that’s where Miriam took her name: Zenzile. Full name, Zenzile Makeba Qgwashu Nguvama.

Zenzi is only eighteen days old when she is sent to prison for the first time! To make ends meet, her mother brews traditional corn beer (“umqombothi”). But the laws of what is not yet officially called “apartheid” policy forbid Black people from consuming or possessing alcohol. Particularly, to produce any. The young kid and her mother spent six months in prison, as the father could not gather the 18-pound-fine required by the police to free them. Later, Zenzi will remember the words that her mother repeatedly told her during childhood: “If you go to prison once, you will go back at least three times.” And she will go back inside a cell more than this during her life.

“Who can stop us from stand back up as long as we have our music?”

Zenzi – Miriam by her English name – is only six when she loses her father. Her mother, busy cleaning the houses of White people, only sees her once a month. But the girl, who lives with her grandmother surrounded by a flock of cousins, already has a taste for singing, and sneaks to attend the rehearsals of the school choir her older sister is a member of. The director spots her and she joins the chorus, then participating in competitions, sometimes singing compositions in Sotho, Xhosa or Zulu language full of metaphors Whites cannot seem to understand… if only they knew! “Who can stop us from standing back up as long as we have our music?”, she thinks already, aware of the unifying and spiritual role of the songs of an entire people. And even today, there is no ANC demonstration without these powerful choirs that carry the history of the struggle of South Africa’s Black people.

Getting back to this young girl who grew up in the shade of a Pretoria’s township, she would soon have to give up music. First she has to leave school, in order to help her mother make ends meet. Like her, she becomes a housemaid in White families, at the mercy of their cruel tantrums. It is 1948, and the National Party has recently won the elections (in which, obviously, only the Whites voted). The infernal legal arsenal of apartheid politics is quickly setting up, brick after brick, barbed wire after barbed wire. Cast in the marble of laws. The interracial relations are banned, the different populations (Blacks, mixed-race, Indians, Whites) must live separately and in reserved areas from which they can not move without authorization. Blacks, therefore, can not go to the white quarters unless they can justify a job, and must prove it by showing their pass, a kind of internal passport for the use of Blacks. Not to mention the Bantu Education Act, which continues segregation in education and also limits the teachings Blacks receive to only what they need to know to serve the Whites. Everyday a little more, South Africa becomes a prison.

This is the context in which Miriam gets pregnant by James Kubay, a young man who is about to become a police officer. She marries him in 1950 and gives birth to a little girl, Bongi (literally “I give thanks to you”). But Miriam’s life is not happy: she is exploited by her mother-in-law and beaten by her husband… She ends up escaping, leaving Bongi to her mother so she can look for a job. One of her cousins offers her to sing for the Cuban Brothers, an amateur orchestra in which he sings himself. The band (that has nothing Cuban) does covers of American standards and adapts songs in the languages of the country. They are really successful in Orlando East, in the suburbs of Johannesburg (where Soweto is currently located). This is where, one night, a certain Nathan Mdledle hears her, and offers her to integrate the Manhattan Brothers, one of the most popular vocal quartets at the time. The only female vocalist of the band, she brings all her grace and tours all over the country with Nathan and his friends. She also records a song that she would often repeat during her career, “Laku Tshoni ’Ilanga”, and “Tula Ndivile” where she handles the lead vocals. That’s when, on the advice of the Manhattan Brothers, she takes her English name as a stage name. Here is Miriam Makeba.

“Come Back Africa”

Starting out in a country that then turned out to feel like a prison, the singer eventually realizes her success and moves abroad.

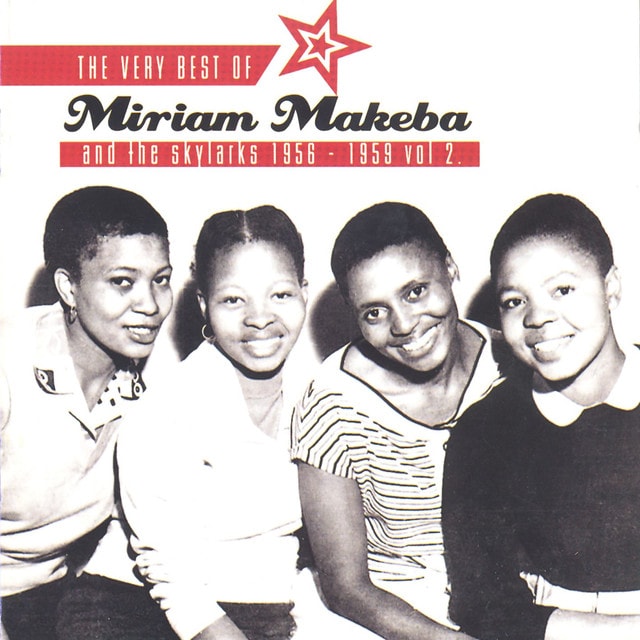

It’s the mid-1950s, and Zenzi Miriam Makeba has made herself known on the stages of her native country. She records new songs with the Manhattan Brothers, and the label Gallotone makes her the star of a new band, the Skylarks.

With her three sisters, she would rehearse on the rooftops of the labels HQ and, as soon as the song was composed, they would all run into the studio to record it immediately, as if they were afraid of forgetting it. The producers in time offer them a tape recorder!

Their repertoire, typical of the kwela jazz era (“kwela” is a small flute used in the South African townships), range from sentimental songs to nostalgic testimonies of the brutal changes their country was then living.

In February 1955, the 45,000 inhabitants (mainly Black, mixed-race, Indian and Chinese) of the Sophiatown district in Johannesburg were forcibly displaced and relocated even further out of the city, into remote suburban areas. Sophiatown had become one of the last areas of diversity in the city. It represented the heart of the city’s cultural life, where Black musicians, writers, dancers and journalists (including those of the famous magazine Drum) rubbed shoulders in the many shebeens, a type of clandestine bar. After evicting its inhabitants, the apartheid regime subtly renamed Sophiatown “Triomf” (for “triumph”). The song “Remember Sophiatown” is a direct reference to these events.

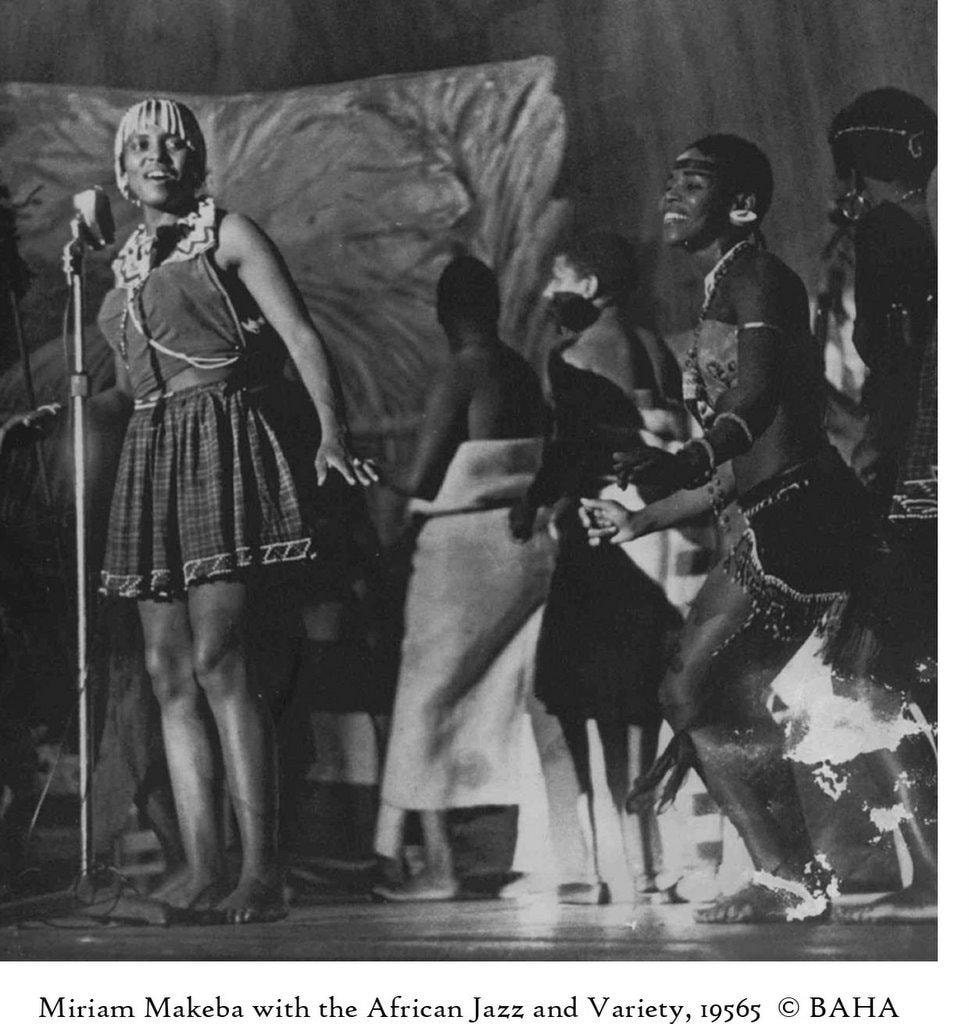

Miriam Makeba appeared on the bill of the African Jazz and Variety show, the first Black show that was allowed in venues usually reserved only for Whites. She shares the bill with her childhood idol, Dorothy Masuka, but also with the first South African star of Indian ancestry, Sonny Pilay. She eventually falls in love with Sonny, despite the prejudices, strengthened by apartheid, that condemned interracial relationships.

The producer of the show – a White man – even succeeds in booking it at the City Hall of Johannesburg, a first for a Black show. This is where filmmaker Lionel Rogosin discovers the singer, and asks her to participate in the filming of a movie. The film’s intention was to tell the life of Black people in South Africa, through the story of Zacharia, a young Black man who moves to Johannesburg to find work. Makeba would play her own role, that of a singer, performing in a shebeen. The film project, titled Come Back Africa (after the name of a song by the A.N.C.) obviously is not approved by the authorities, forcing the team to shoot clandestinely. Miriam’s scene is shot in the middle of the night, at one o’clock in the morning. In the shebeen, a group of men are in the midst of a conversation about politics. When they see Miriam come in, they ask her to sing for them.

The director then asked Makeba to apply for a passport. He sought to share her talents outside of South Africa during promotion of the film.

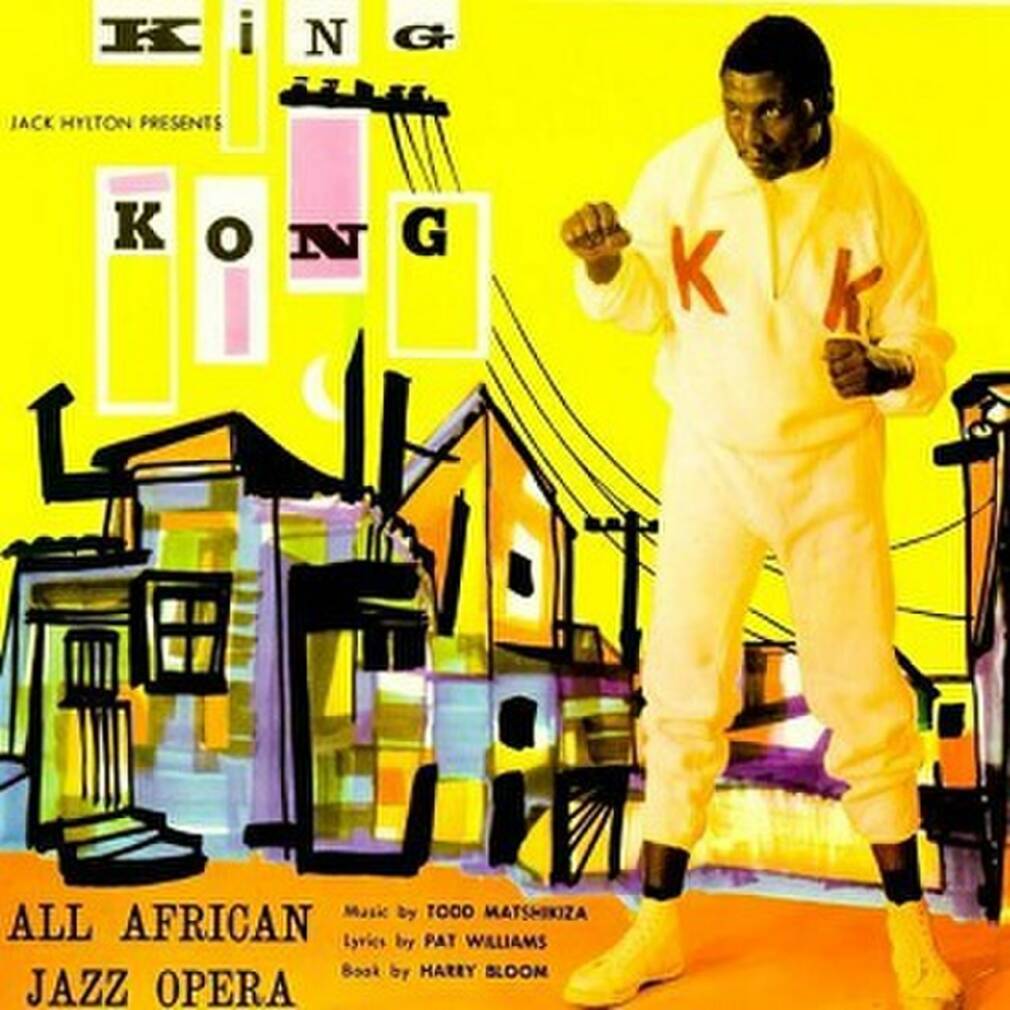

Having just finished an extensive tour (18 months) with African Jazz and Variety, she directly takes on one of the leading roles of a jazz opera titled King Kong, a tribute to the life of famous Black boxer, Ezekiel Dlamini, nicknamed “King Kong”. The White authorities prevented him from participating in fights abroad, to avoid him defeating White boxers and returning home as a hero. King Kong sank into alcoholism and ended up in jail after killing his girlfriend. There he would meet his suspicious death, where he was found drowned in a shallow waterhole…

White people produce, write and stage the show. All are Jewish, and are undoubtedly more mindful of the violence of segregation which recalls the situation of the Jews of Germany on the eve of the Second World War. Makeba emphasizes this point in her autobiography: “It is a fact that Jews run the theatre industry in South Africa. And it is a fact that Jews were the only ones to help Africans. In the theatre we are not forced to call the director “Baas” (“boss”) just because he is white; we call him boss because he is who directs!” Nathan Mdlhedlhe and Joe Mogotsi, her fellow comrades in the Manhattan Brothers, respectively play King Kong and his best friend, Lucky. As for Miriam, she holds the role of a shebeen queen: both the boxer’s girlfriend and the owner of a clandestine bar called Back Of The Moon. This is the title of one of the signature songs she performs on stage and on record. Among the musicians, she becomes friends with a young trumpet player named Hugh Masekela, already destined for a great future.

The show is a success, and is sold out in Johannesburg for six months. The producers managed to get around the laws of apartheid by programming King Kong in one of the few places of racial diversity, a campus of a university! Therefore, all audiences are welcome to attend.

On the eve of a tour of the provinces, the singer passes just outside a hospital… but as the building is reserved for Whites, they have to transport her 20 km away! She is operated on there, and is diagnosed with an ectopic pregnancy. She has to be substituted for a few weeks before rejoining the troupe in Cape Town. She then receives news from Lionel Rogosin, the director of Come Back Africa. He asks her to join him at the Venice International Film Festival to present the movie. It is then that Miriam remembers a prediction made by a spirit (“amadlozi”) speaking through her mother’s mouth – she became a “isangoma”, a medium and a traditional healer. The mind spoke for her: “Miriam will leave South Africa for a long journey and will never come back.” She doesn’t really know if she should believe it, but before flying away, she makes one last stop at the studio and records “Miriam’s Goodbye to Africa”. A farewell song penned by Gibson Kente, whose impact she may not yet have fully measured. She also recorded one of her best-known songs, “Iphi Ndilela”, which in Zulu language means “I ask you to show me the way”.

“Take care, my people,

“Iphi Ndlhela”, 1959

I am leaving

I’m going to the country of the White man

I ask you to be with me

To show me the way

We will meet again on my return

I make this promise”

She flies out to Venice in August 1959. Without knowing yet that a new life is beginning for her, under the celebrity spotlight, on the North American stages and in the ceremonies of independence of an Africa which would free itself from the colonial yoke. Nor does she know that when boarding South African Airways plane, she would not see her home country again for the next 35 years.

“Miss Makeba”: thrown in at the American deep end

After having achieved great success in her country where the noose of apartheid tightened on Black people, the young singer flies away from home. A new life begins. A life of success, commitments, and exile.

When she arrives in Venice in August 1959, after stopping by in London and Paris, the young Miriam Makeba is still very much unknown outside of South Africa. But Come Back Africa, the film in which she makes a brief appearance with two songs, will be shown in the Italian city, as a world premiere, to the audience of the Venice International Film Festival.

The director, Lionel Rogosin, takes her under his wing and excitedly informs her that friends to whom he has shown the film are waiting for her in the United States: one wants her on his TV show – the renowned Steve Allen Show; the other wants to book her at the Village Vanguard, a famous New York jazz club. In Venice, the film wins the Critics’ Prize and Miriam Makeba is taking in the surprise of suddenly being followed by photographers (see photo below).

On a path to an international career

After the success of Come Back Africa, she leaves for London with the director of the film, waiting to receive a visa allowing her to travel to the United States. She takes part in the BBC television show, In Town Tonight, where she sings “Back Of The Moon”, one of the songs featured in the movie.

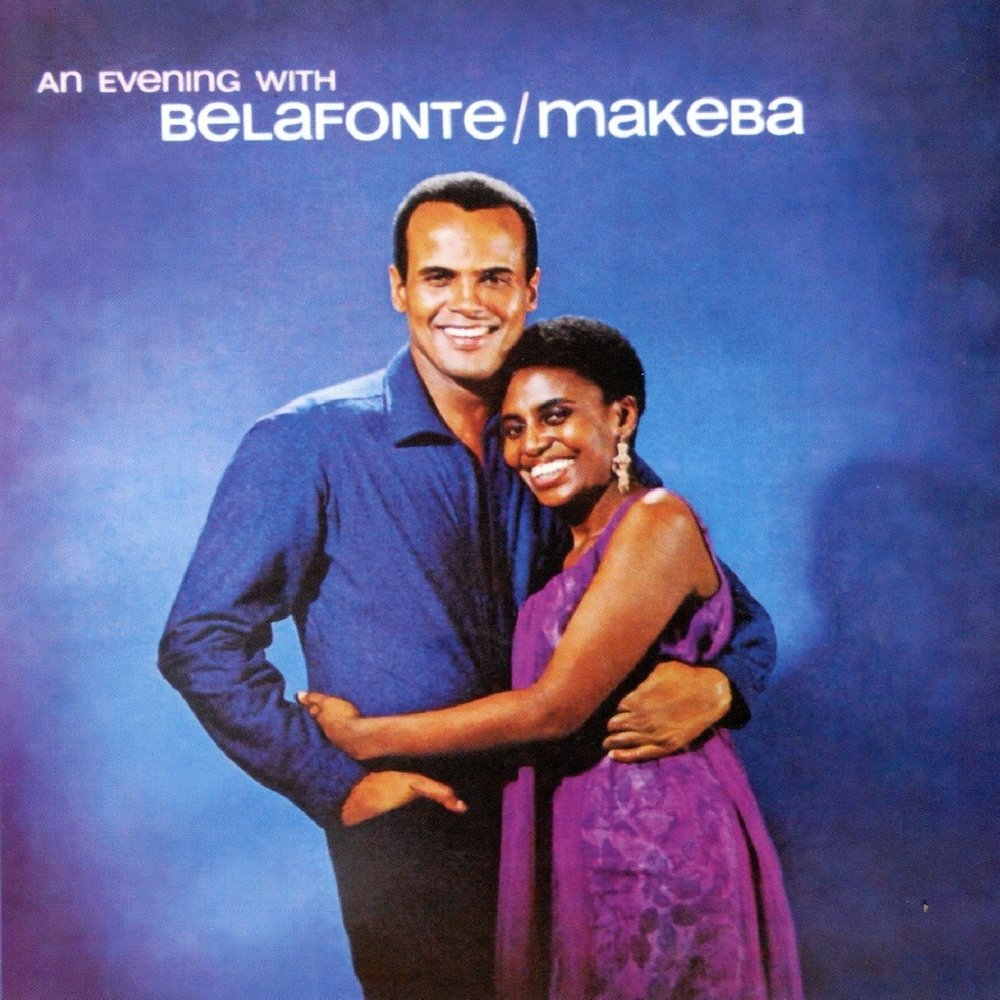

While visiting London, the singer and American activist Harry Belafonte, watches the show, and arranges to meet her the next day at a screening of the film. He promises to help her during her stay in the United States. Firstly he obtains a visa for her, and organizes a trip to Los Angeles for the Steve Allen Show, which is watched by no less than 60 million viewers! She leaves shortly for New York, as she is about to begin a four-week residency at the Village Vanguard.

Belafonte’s team, whom she nicknames “Big Brother”, have her hair styled in the era’s current fashion: straightened. On the very first evening, she then rubs her hair under water, and it returns to its natural appearance. This is the natural hairstyle that soon African-American women will imitate and call “afro”. Makeba has only just arrived, but she had already created a new fashion sensation.

In Village Vanguard’s dressing room, her new mentor Belafonte informs her that the African-American artistic elite had come to listen to her. In the front row, sitting at the tables of this crowded club, are Duke Ellington, Sidney Poitier, Nina Simone and Miles Davis. Not bad for a debut show!

She sings “Jikele Mayweni”, “Back Of The Moon”, and the famous “Qonqgothwane” that journalists will come to name “The Click Song”. Following her residency at the Village Vanguard, she is hired at the Blue Angel, a glamorous club in New York, where Lauren Bacall attends her show. The Times wrote: “She is probably too shy to realize it, but she would create a very noticeable void in the American entertainment world, where she made her entrance just six weeks ago.” In short, America smiles at Zenzi (diminutive of her first name Uzenzile), and she starts to become recognized in the street.

From apartheid to civil rights, the struggles come to life

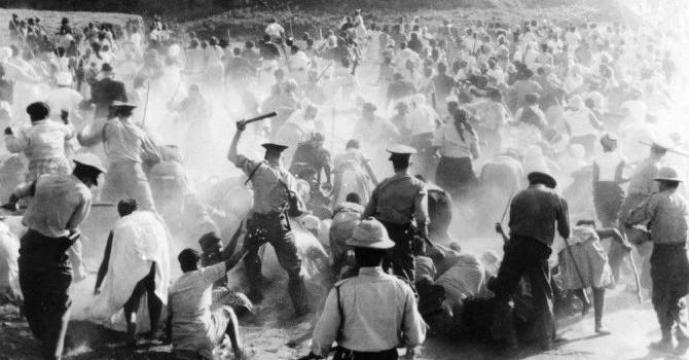

She accompanies Harry Belafonte on tour, sings for an SCLC benefit – an organization whose president is Dr. Martin Luther King – and learns to cope with the Southern states’ persistent racism. In her autobiography (that she co-wrote with James Hall), she tells how her, Belafonte, and fellow musicians are denied entry to a restaurant in Atlanta because they are “colored”. Belafonte immediately summons the press to the restaurant and holds an impromptu press conference outside, comparing the situation of the “Jim Crow law”-gagged South with that of apartheid-ruled South Africa. Moreover, Belafonte would come to organize a press conference before each one of the shows, while he expanded on the situation of Blacks in the USA, and how she tells that of South African Blacks. Certainly, in her country, the situation becomes more tense every day: the government brutally represses the peaceful demonstrations that protest against the “pass” – a passport every Black person needs if they want to move from one district to another. In Sharpeville, there are 69 dead and 178 people wounded.

The PAC (Pan African Congress) that organize the event, as well as the ANC are banned and must go clandestine. The ANC leaders then decide to found “Umkhonto we Sizwe” (“Spear of the Nation”), the armed wing of the party responsible for harassing security forces of the apartheid regime. Nelson Mandela and Joe Slovo are elected to run the activist group.

Makeba is well aware that she is the only Black South African to have easy access to the media. Chaperoned by her “Big Brother”, she will shortly make the most of it. For now, she manages to bring her daughter Bongi to the United States. A few weeks later, while she is performing in Chicago, she is notified that her mother has died. At the South African embassy in Washington, where she needs to extend her visa, the civil officer stamps her passport: “out of validity”! She become stateless, and is prevented from returning home to bury her mother.

Her native country whose voice she bears, will only be seen again 34 years later. Her political commitment becomes stronger. While based in New York, she meets various African delegates whose countries have just achieved independence.

On July 16, 1963, she speaks at a UN meeting before the special committee on apartheid, to challenge the nations of the world and ask them to put pressure on Pretoria. She is only 29 years old.

From then on, her records are banned from sale in South Africa.

But in the United States, her success is growing. Invited to sing at President Kennedy’s birthday in 1962, she also appears in the famous Ed Sullivan Show, another big TV show that propelled Elvis, The Doors, The Beatles and the Jackson Five. She is introduced by her “Big Brother», Harry Belafonte.

It is then with him – in 1965 – that she receives a Grammy Award, the highest North American award in the music industry, for the album An Evening With Belafonte & Makeba (which features their duet “Malaïka”). It is Belafonte who signs the text of presentation of the album, recounting his meeting with the woman who, for nearly a decade, would accompany him on all the North American stages.

She also meets Marlon Brando, one of the few White stars to ask her about the situation in South Africa. He also offers her a platform to make a speech at the premiere of The Ugly American in Washington, in front of an audience of celebrities.

At the end of 1963, the singer falls sick. And the brutal verdict is given: cancer. Belafonte, and her other friends organize themselves so she can be operated on quickly. She will survive, but around her, darker clouds are piling up in her adoptive country’s skies. In the hospital room, she learns about the assassination of President Kennedy. Barely recovered, she resumes performing concerts, where she never misses an opportunity to talk of and denounce the situation of her country.

Although she picks up again her career in the United States, performing concert after concert, and even winning a hit with a new version of “Pata Pata” (composed in 1956 in South Africa), Makeba’s fate is being spelled out, more and more, in Africa. The shy girl has gradually become the ambassador of a continent in full steam, rich in an ideal that she will embody: unity. She gains a new nickname: “Mama Africa”.

How ‘Miss Makeba’ became ‘Mama Africa’

Backed up by her success in the United States, the songstress has now become the voice of her people. It did not take long before the whole African continent adopted her, in particular the forefathers of independence. This is how Miss Makeba becomes Mama Africa.

It’s in New York that Miriam Makeba is introduced to the rest of Africa. She makes friends with delegates of the newly independent African countries who sit at the United Nations, and she even welcomes to her own home young students arriving from the continent. She also hosts Tom Mboya, a young Kenyan executive heading for a clerical function in his soon-to-be-independent native country. She embarks on a fundraising trip of America with him to finance scholarships for students in his country (80 of which will have their studies paid for). In 1962, Mboya invited her to Kenya to perform at a benefit show for orphans of Mau-Mau. This is how she comes to set foot in Africa again, three years after leaving South Africa – a country from which she was banished. This trip would lead to many others. It continues to neighboring Tanzania, where President Julius Nyerere, learning that the singer has become stateless, offers her a Tanzanian diplomatic passport. A few months later, in 1963, she is invited to the inaugural conference of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa. There she meets Hailé Sélassié, who offers his desk so that she can change clothes before performing for the various heads of state. Political leaders are fully under Makeba’s spell, and Guinean president Sékou Touré sends one of his literary works to her hotel, duly autographed.

Upon her return to America, she falls sick. She is diagnosed with cancer. Wishfully her friends (Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando) as well as African delegates to the UN wait on her hand and foot. In time, the operation is a success, even if it prevents Miriam from having another child, alongside her daughter Bongi. At the end of the year, she returns to Kenya, where Jomo Kenyatta, the country’s first president, invites her to the official ceremonies of newly-gained independence. Then, she continues her journey to Côte d’Ivoire [Ivory Coast] where she is a guest of the Houphouët-Boigny couple. In order to make them aware of the situation for Black people in South Africa, she lends them a copy of the movie Come Back Africa which turned her famous. She then sends the film on to Sékou Touré, in Guinea.

Not long after, the Algerian president would offer Makeba her second diplomatic passport. Over the years, she would accumulate almost a dozen of these, offered by authorities of African countries that recognize her as the ambassador of her people and the embodiment of a dignified, determined, and struggling Africa. The struggle still however continues.

The struggle continues, there in the United States too

Makeba keeps on fighting, first to denounce the segregationist regime in South Africa – during press conferences she holds before her concerts – and, in 1964, before the UN special committee where she was invited to speak again. Then in the United States. In 1965, Malcom X is assassinated (she would pay homage to him later with the song “Brother Malcom”, written by her daughter). The same year, riots break out in the Black district of Watts, in Los Angeles. Violence reminding her of the escalating situation in South Africa. Her marriage to the trumpeter Hugh Masekela falls apart, as does her companionship with Harry Belafonte. So when Sékou Touré invited her to Guinea for a festival, she jumped at the chance.

In Guinea she meets another African-American activist, also invited to the congress party as a representative of Black people in the USA. His name: Stokely Carmichael, a revolutionary, advocate of the civil rights and supporter of the Black Power philosophy. To the American authorities, Carmichael is seen as a dangerous troublemaker.

It’s with him that the next chapter in Miriam’s life would develop in Guinea. She only understands this when she returns to the United States in 1968, where the now-official couple are harassed by the FBI. The singer herself is followed on all her travels, her concerts are cancelled, and soon a certain number of the Commonwealth countries, which have already banned Stokely Carmichael, let her know that she too is not welcome any longer. In the United States, doors begin to close one after the other. She even fears that her new husband would end up assassinated by Eldridge, a leading figure of the Black Panther Party, an organization Carmichael had come close to, before deep disputes broke out.

Eventually, ten years after arriving in the United States, Miriam Makeba feels it is time to get back on the road. The road of exile, once again. The new destination is an obvious choice: Guinea, where Sékou Touré has been insisting that she comes to settle.

The Guinean period

The Guinean President, the only person who voted against the 1958 referendum proposed by the French government to create a political association with its colonies, becomes almost a secondary father to the singer. When he learns that she is marrying Stokely Carmichael, he organizes their wedding reception in New York.

Shortly thereafter, he welcomes the couple to Conakry with open arms, and invites them to settle down at Villa Andrée, one of the official guesthouses of the Guinean State. Miriam is impressed by the efforts the country makes in terms of culture, organising its famous regional competitions which culminate at Conakry’s National Festival. Dance troupes and traditional music groups, modern orchestras (the Bembeya Jazz; Keletigui et ses Tambourinis; etc.) compete to revitalize their country’s culture, almost killed off by decades of colonial brainwashing. In Guinea, Black Power is staying for good.

Makeba recruits Guinean musicians, and performs regularly at the Palais du Peuple, often at the request of heads of state on official visit to Guinea. Then, without a manager in the United States, the Guinean Presidential Office becomes the main contact for those who want to book her show, wherever they are in the world.

From her performances in Guinea, there exists a famous live in Conakry recorded performance and a few tracks which she recorded at the time for the State-run label Syliphone.

Conceding to the period’s propaganda ruling, she sings the praises of the political leader with “Sekou Famaké” as an example, which she performs in Malinké language. Singing in the local languages of the country she performs in, would become a trademark of Makeba’s – with an exceptional moment at Algiers’ Pan-African Festival in 1969 where she sings a song in Arabic, a habit she would continue over time. She became a grandmother (her daughter Bongi gave birth to the baby Lumumba), and took her grandson along with her. Stokely Carmichael is also invited to the Panaf’, as are the Black Panthers who arrive in numbers. The singer fears for her husband, as Eldridge Cleaver’s threats could become a reality, now that both are present in Algiers. In her autobiography, she tells of how, returning from a concert, she could not find her grandson whom she had left under the good care of Stokely Carmichael. Seized by panic, she cannot reach her husband. Following long hours of waiting, Stokely eventually appears with baby Lumumba… returning from a meeting with his rival from the Black Panthers. Dumbfounded, she then comes to understand that her husband took the child with him to discourage any violent action on the part of Cleaver. Finally, the family returns to Conakry, where life is not exactly a picnic either.

Mama Africa

In November 1970, she has a front-row seat for when mercenaries hired by Portugal arrive by sea to terminate the Sékou-Touré regime and the support bases he offered to the PAIGC – African Party for the Independence of Guinea [Bissau] and Cape Verde – which is about to defeat Lisbon’s colonialist power. She tells how the populations themselves, organized in militia, take up arms, and with the help of the Guinean army eventually defy the invasion (this event is recalled in Bembeya Jazz’s song “Guinean Army”). Shortly after, in 1975, the Portuguese regime would lose their empire and Miriam Makeba would sing in Maputo for the independence of Mozambique, followed by Angola. As she liked to put it, “every time a country gains independence, we call Miriam”. It is at this moment that she receives the nickname “Mama Africa”, the title of a documentary Swiss television devoted to her. No one can be more Pan-African than Makeba. And not only through her songs.

In Guinea, Ahmed Sékou Touré does not only offer her a diplomatic passport, he sends her to the UN general assemblies as an official delegate of the Guinean delegation, and on two occasions, would ask her to deliver the official speech of Guinea, before many heads of state and government. It is a way to highlight Guinea, embodied by an internationally known figure, and to denounce apartheid which persists in South Africa. Suffice to say that in the mid-1970s, few women in the world had this privilege.

Miriam Makeba’s years in Guinea consist of ups and downs. She is delighted to launch a baby clothing store, which would soon collapse after she decides to sell at a significant loss in order for poor people to be able to afford her products. She then launches a nightclub, Le Zambezi, which would shine for three years before an abusive landlord decides to increase the rent for a skyrocketing price. And above all, her talented daughter is regularly subject to fits of madness. Her youngest child, Themba, son of percussionist Papa Kouyaté, dies while treated at an under-equipped hospital, plunging Bongi into even greater distress. As for Miriam, her marriage to Stokely Carmichael eventually falls apart, as he becomes infatuated with a young Guinean woman. Repeated hard blows endured with sadness, but never ceasing to hold her head up. She takes refuge at times in the house she built in the hills of Fouta Djallon. The house still stands, simple and beautiful, worn by time, and the few remaining pieces of furniture allow the ghost of the diva to continue to float through the air.

The death of Sékou Touré in 1984 marks the end of a happy and prosperous African period, in the shadow of the Guinean president, whom she refers to as her sponsor and mentor. She never had a word to criticize him, his authoritarianism, his paranoia and the political prisoners he sent to die in the sinister Camp Boiro. Likewise, she never spoke of the deterioration of living conditions in Guinea, whose economy at the end of the 1970s was completely drained. This could to some appear surprising. It could be that the hospitality of a man and his country exceeded everything else, and the fight for the freedom of a continent, grappling with imperialism, was worth avoiding any criticism of that would have certainly weakened a much needed African unity. She would always follow this code of conduct, including in Zaire where she does not hesitate to sing the praises of Mobutu during the Rumble in the Jungle (1974) gathering, or even at Festac (World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture) – an event organized by the military junta in Nigeria (1977). No doubt she also believed that she and her country needed the support of all the other countries of Africa in order to end apartheid. An opinion not too far from the views that Nelson Mandela exposed on a television program on ABC channel in 1990.

The change in power in Conakry – with Lansana Conté taking power by force after the death of Sékou Touré – and, moreso, the death of her daughter Bongi, would convince her to hit the road again. “Mama Africa”, while being welcomed with all due respect everywhere in Africa, still cannot return to her own home. This reality strikes her down when she is forced to bury her daughter far from the land of her ancestors and from family she could never meet. At the same time, international pressure on South Africa, where the situation is more explosive by the day, makes her believe that her return may appear soon. In 1985, she leaves Guinea to settle in Brussels, Belgium, and continues the fight…

The exile ends, but the struggle continues

In 1985, when both her protector Sekou Touré and her daughter Bongi passed away, Miriam Makeba left Guinea, where she found refuge for over 15 years. A new and unexpected chapter in her life begins. She settles in Brussels but as always, makes sure to keep tabs on the situation in her native country.

In South Africa, the situation has reached the point of no return: international pressure – in the form of a boycott – is tougher, and township residents – now hopeless – are no longer afraid of the confrontation, despite the ever more violent repression that falls upon them. The apartheid regime is not dead yet, but it struggles a bit more each day to hold itself together. Moreso as informal talks are about to begin following the transfer of ANC leaders from Robben Island prison to Pollsmoor prison. In November 1985, the Minister of Justice visits Mandela. On the outside, artists take take hold of the cause and make it resound from Western stages.

In 1986, Paul Simon invites Ray Phiri and Ladysmith Black Mambazo to perform on the Graceland album, opening the doors to South African music, still little exposed to Western audiences. He is criticised for ignoring the boycott (decreed by both the UN and the ANC) which prohibits foreign artists from collaborating with their South African colleagues for as long as this racist regime was in power. He organizes a major tour in 1987 inviting Miriam Makeba and her ex-husband who still remains her friend, Hugh Masekela. The tour passes through Zimbabwe, a newly-freed country from 1980.

The two exiled musicians also take part in the huge concert at Wembley, celebrating 70 years of Mandela, at this stage still imprisoned. An 11-hour show is broadcast worldwide, featuring Whitney Houston, Sting, Simple Minds, Mahlathini & Mahotella Queens Aswad, UB40, Youssou N’Dour, Salif Keita, Peter Gabriel, Joe Cocker, Stevie Wonder, Tracy Chapman… Johnny Clegg’s hit “Asimbonanga” becomes an international hit. As Mandela writes in his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom: “Politics can be strengthened by music, but music has a potency that defies politics.”

Makeba is certainly aware of the power of music, becoming in 25 years the only chosen spokesperson of her people on stage and in important meetings the world over. On February 11, 1990, Mandela, who has not been seen (“Asimbonanga”) since his arrest in 1962, is finally released. Miriam is no doubt happy, but still feels apprehensible, stating: “The release of Mr. Mandela does not signal the end of apartheid. The sad thing is that he spent most of his life in prison trying to fight apartheid, and today he is still released under the apartheid regime. So nothing has changed here.”

Returning to her country, after 31 years of exile. And the struggle continues.

But “Madiba”, “our father” as she calls him, urges her to return to her country. Just before taking her flight, after 31 years in exile, she tells French radio station RFI that the first thing she will do is “go and pray at my mother’s grave, that’s why I’m leaving here, because I was forbidden to return to her funeral. I will stay with my brother. He’s the only one I have left, there are only two of us, head and tail. […] I will sing in Soweto, when the time comes.” She lands on June 10, 1990 in Johannesburg with a French passport, given to her by the president’s wife, Danielle Mitterrand. A few months later, she finally performs on stage for the people of her country. The following year she performs alongside Whoopi Goldberg in the movie Sarafina!, depicting the Soweto riots of 1976. Despite apartheid officially ending in 1994 with the election of Mandela, she continues to fight other issues, which concern her own country and the rest of Africa.

Together with Madiba’s new wife, Graça Machel – widow to the former Mozambican president – she launches into a life supporting children with AIDS-HIV, and opens a center to help reconstruct the lives of orphaned and young sexually-abused girls in South Africa. She continues to record music – releasing four albums up until 2008 – and performing on stage, taking her new battles with her to everywhere she performs. She may have embarked on a “farewell” tour in 2005, but still continues to sing to support the causes close to her heart. A goodwill ambassador for the FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations – since 1999, she returns in 2008 to DR Congo to protest against sexual violence to women, in a region crippled by armed militia.

Six months later, without hesitation she visited Naples for a benefit and support event of Roberto Saviano, an Italian writer who denounced the mafia, whose criminal activities also affect the African immigrants they exploit and eventually dispose of…

It is there, at Castel Volturno, on November 9, 2008, that she performs for the last time “Pata Pata”, before collapsing backstage, falling victim to a heart attack. She was 76 years old.

“She was South Africa’s first lady of song and so richly deserved the title Mama Afrika,” wrote Mandela the next day in a press release, before adding, “she was a mother to our struggle and to this young nation of ours.” “Mama Africa”, who liked to recall “I do not sing politics, I only sing the truth”, sung until the very end, as exclaimed in “I Shall Sing”. A profession of faith that could serve as her epitaph.

I shall sing

“I Shall Sing”

Sing my song

Be it right

Be it wrong

In the night

In the day

Anyhow, Anyway

I shall sing”

THE END

Feature first published in a series of articles in 2018.