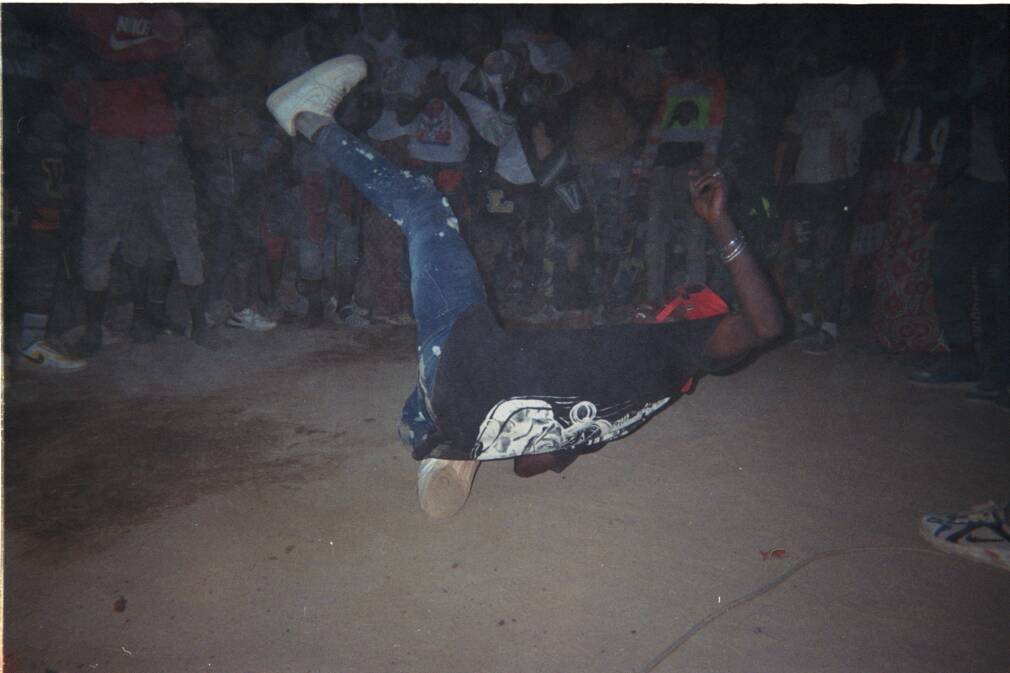

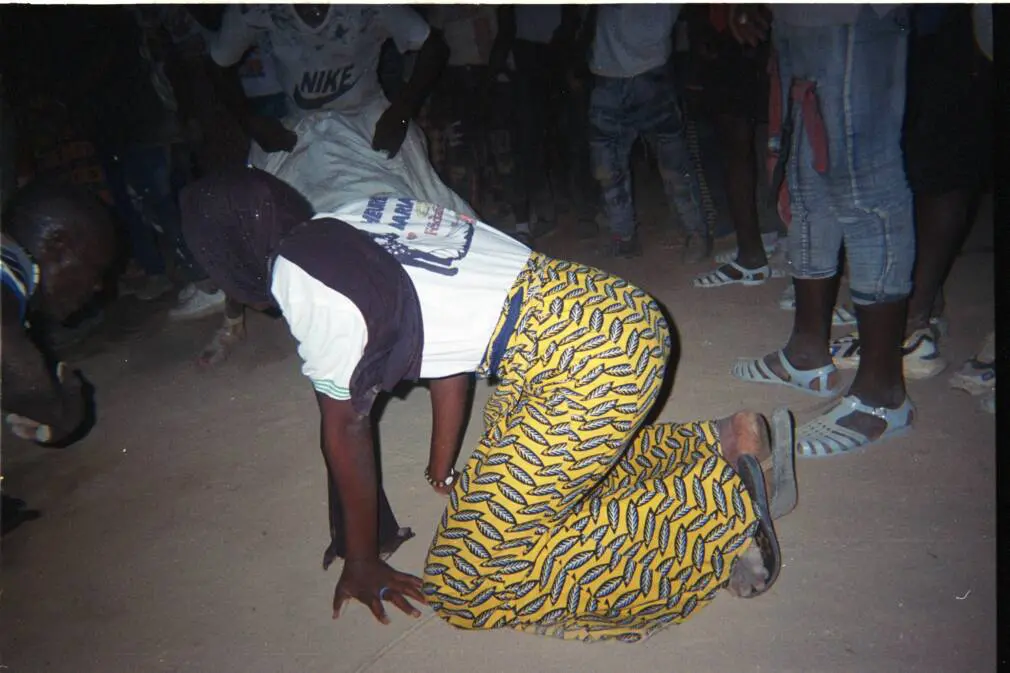

Waists thrust at everything, pounding, shaking, and sending up billowing clouds of dust. Far from the city, particles fly in every chaotic direction as hands and feet beat at the earth. At the Balani Show, bodies are possessed, the tempo increasing to a sudden swarm of moths as dancers judder beyond themselves.

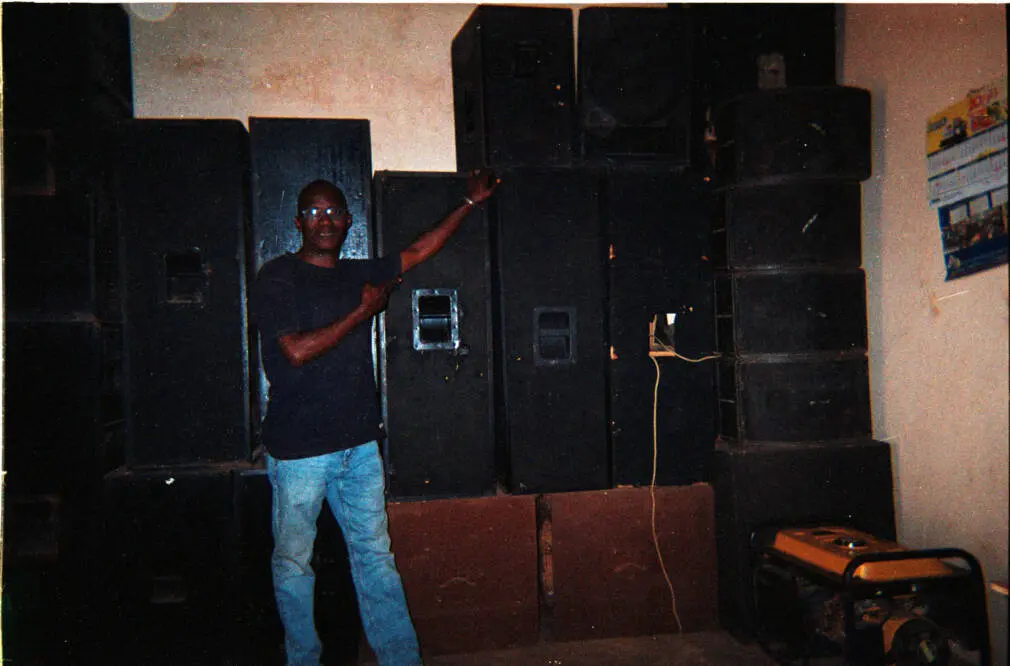

We course south, around 40km from Bamako, in a rusted jeep, past flour processing plants and pharmaceutical factories to join a bumpy track requiring expert navigation. There is a real sense of being cut off from the world. Strange birds with long necks swoop low and squawk at the disturbance as we arrive in a tiny village near Sanankoroba. Apart from communal taps, there is no running water, very little electricity, and a biblical number of frogs. n a clearing behind a desk, surrounded by huge speaker stacks, DJ Diaki explains that I had to visit his region of Koulikoro to experience Mali’s unique festivities at their best.

Diaki is a stalwart of the scene, a hellraiser whose sets often exceed 200bpm. He is no stranger to the cosmopolitan venues of Paris and Berlin, but right now, it seems nothing could be more exciting than playing this remote rural community, living off the land in the bush. “Tonight, you will see what the village youth will bring“, he says. “We play for them, and they will want it faster than anywhere in the city.” He draws hard on a cigarette as his apprentices, DJ Iba and DJ Gladia, look on. “What we bring, Bamako’s DJs cannot! Someone from the West might believe that the people tonight are on drugs, but not here. Together, we create good times and optimism. We are transported through dance.”

Diaki and his acolytes do not work in isolation. Mali’s Balani Show festivities showcase two fundamental aspects of West African culture: the balafon, a wooden marimba-like instrument of the 12th century, that rings out joyfully when played at dextrous speed, and the custom of celebrating life’s most sacred moments in front of your home—whether in the village or on the street.

Once amplified only by the gourds beneath its keys, the balafon is now commonly played through speakers using a microphone to capture its melodic buzz and percussive hammerings. The technology of the late 1990s took this traditional sound to new realms when sampled and sped up on basic computer software. The djembe drum, now replaced with electronic beats, compels dancers to jerk their frenzied bodies harder than ever to the sound of the future past.

By sundown in the village, we are delving into a scalding pot at our feet, bringing handfuls of rice and meat to our mouths, spitting out the tiny bones of charcoaled rabbit onto the ground. Teenage boys pour us mint tea and set up the petrol generators, pulling at wires in the dark. Once the final prayer dissipates from the tannoys of the village mosque, the energy becomes focused on the party. Children in plastic sandals gather around, pressing for the music to begin. Plugs snap into sockets, more wires get fed, laptops are flipped open, and a shocking sonic explosion booms into wide open space under a huge multi-layered cosmos.

I first met DJ Diaki at his label’s Nyege Nyege festival on the banks of the Nile in Uganda. Dressed in a suit while smoking a cigarette and occasionally swigging from a bottle of water, he unleashed disorder from his PC keyboard, triggering waves of euphoria from the crowd. This is nothing unusual for the man known as ‘Le President’. Diaki, born Diaki Koné, has taken Malian high-energy balani music and made it his own, playing festivals as far afield as Australia. From DJing Soukous and Coupé Decalé cassettes, he has evolved to producing his own hyper-tempo style that he calls Balani Fou (Crazy Balani), a seething collection of stripped-down polyrhythms capable of driving dancers into altered states.

Young people arriving in Bamako from the countryside have contributed to the stimulation and reinvention of the city by bringing their parties with them. Their Balani Shows, already a phenomenon in the bush, introduced high-tempo, jubilant music played by young musicians to the street. It is music forged of a fusion between the traditional and the modern.

Certain Bamako media outlets have raged with moral panic for years, describing Balani Shows as a threat to the fabric of Malian society, the parties disturbing peaceful citizens throughout the night. They claim that lewd and dangerously provocative dancing, along with alcohol and drug consumption, increase the risk of “degrading” acts between teenage boys and girls. With Mali in a state of instability and swathes of the country at risk from insurgency, articles have called for a reduction of these parties to keep its citizens safe from acts of terrorism. They have had the desired effect. Parts of the city have clamped down: in August 2023, the town hall of District IV in Bamako decided to ban all “cultural and artistic events known as ”Balani Show”…with all non-compliance to this municipal decree punishable by a fine of up to 500,000F (around $800)”. With other parts of the city likely to follow suit, it has forced the celebrations to relocate – yet almost as soon as I set foot in the country, it becomes obvious that not all festivities have been banned from Mali’s streets.

On my first Sunday in Bamako, I wandered aimlessly through an amorphous neighbourhood close to the endless Niger River. Seats had been lined up beneath lightweight marquees as a street wedding stirred up an unrestrained thrill from the congregants. Their bodies wrapped in tailored bazin, a colourful hand-dyed material, reflected the afternoon light in many hues. A band played on a rug before us. When the singer, dancing like a hypnotised snake, shouted “ALLEZ!” into a distorted microphone, an electric guitarist covered in silver jewellery played a delirious spiral of notes that drove the drummer wild, thumping his kick drum furiously and pinging his high-pitched ringing snare: KLAK-KLAK-KLAK. Women rocked their bodies, facing each other, slowly moving their shoulders back and forth. The rest of the wedding party sat placidly in the shade on white plastic garden chairs.

A few streets away, I turned a corner to stop abruptly. Only a short distance ahead, men were lined up silently in columns about to undertake the prayers for the dead. Unblemished goats tied to trees, as still and as white as untrodden snow, waited to be slaughtered and shared among the attendees when the incantations were over. Lips moved, hands were folded and held to chests, and the community called out for forgiveness for someone who could no longer do so for themselves. Someone’s father was gone, and whatever was left of them poured out of us in sweat. Life’s major events come to pass, but one bleeds into the other in Bamako; the intersection of grief and joy is mapped out before you from street to street.

Earlier that day, I had met MC Waraba, a rapper who was a child in the late 90s when the Balani Shows first became a phenomenon across Bamako. As we wandered through the city’s sprawling market, voices recorded on battery-powered tannoys repeated the prices of things on a maddening loop. The honking of horns from buses, motorbikes and taxis never ceased. Teenage boys called out when they recognised the bearded 36-year-old. He acknowledged them by hollering back. “In my neighbourhood, my aunts and uncles would celebrate everything by setting up sound systems. The djembe and conga drums playing furiously along to the balafon was a big party.” He is enthralled by the memory of MCs hosting feverish dance competitions.

“It was our time to get the vibe going,” Waraba says of his early twenties. Grabbing the microphone allowed him to shout out his love for his country and proclamations to his community, asking girls to stop using whitening cream – while also declaring his passion for huge asses. The music he made with Mélèké Tchatcho “was heard all over Mali. We took something from the ancient Mandinka culture from the old Mali Empire and fed it to a new generation.” Waraba doesn’t see his future rooted in the balani sound, following the trend for Afrobeats instead. But he remains indebted: “Balani Shows not only united us on the street. The happiness from this time has made me who I am as an artist today. Everything comes from my love for these moments as a child.”

Back in the village, as Diaki hits his stride, a hundred children begin thrashing their arms and legs, dressed in t-shirts, tracksuits and football tops of mostly Champions League football clubs. They dance enthusiastically to the music thumping into them from the speakers. Some drop to their knees, lifting themselves up and down in convulsions; others, practically on tiptoes, cross their legs back and forth with intense focus. Having fun for some becomes a very serious business as the festivities take hold. From the sidelines, young mothers arrive to survey the scene.

One of the village’s young men waves a stick to keep the kids from the equipment. The dancers get closer, and he swooshes it in the air as a warning and then whacks it to the ground. The children leap back, dancing at wild angles. A boy in tiny pink shades stands still, watching it all go down around him from the dancefloor. From the edge of the melee, others with their arms crossed timidly look on.

With a cigarette dangling from his lips and a large gold chain from his neck, Diaki’s protege DJ Gladia is effortlessly cool, remixing tracks live as his friend directs the dancers from the mic. The man with the stick makes his own announcement, and then the village women proceed to make a formation. All the attendees form a circle around them as they face each other, bopping as one. Some have tiny babies swathed around them. Their heads bubbling against the warmth of their mother’s skin. A yellow moon has now risen and started to arc across the sky at full tilt.

Away from the wild parties, contemporary artists in Mali have reinterpreted the balafon to popular appeal. When walking through Badalabougou in Bamako, I stumbled upon an Islamic baptism. White light glinted blindingly off the metal pots heaped with food as children ran round and round in circles, as if in a dream. When the sound of Abdoulaye Diabaté filled the air from a stereo, smiles were at every turn. A romantic griot from the region of Segou, Diabaté honoured the balafon by placing it centre stage in his ‘90s party hit “Balani”, alongside his electric guitar and the driving pulse of a western-sounding drum kit. It swept the nation as an ode to Mali’s ubiquitous, soul-stirring tones.

DJ Seydou Bagayoko was one of the originators of what is considered a Balani Show, shifting the onus away from paying balani musicians to DJing with music cassettes, but it is his apprentices, DJ Diaki and DJ Sandji, who went on to carve out their own careers with an electronic sound. I tracked down Sandji to ask him about his role in deconstructing balani music on Bamako’s streets.

Born in 1975, his first exposure to music was his father strumming on an acoustic guitar. However, a particular show on Radio Mali every Sunday morning, from 10 until noon, captivated him. “I would eagerly tune in to ‘Disque Demandé,’ not only for popular Malian music but also Congolese, Zairian, and European hits.” Turning his back on education, Sandji believed his life should be dedicated to hosting the local party scene using his big brother’s microphone and playing dance music. “Just as on the radio, where songs were dedicated to individual listeners, I called out people’s names on the street.” At 18, he became popular in his neighbourhood but drew ire from local imams for creating too much commotion. “I even surrounded myself with sheep and huge bags of flour to make it a theatrical experience,” he laughs. “People don’t understand that when you are poor, you cannot go to bars or nightclubs, and not only because you have no money. Your family’s eyes are on you. Everything has to stay local.”

This period lifted artists to new levels of stardom, and Molobaly Keita’s long career was at full peak. Performing live on radio and television, his explosive, airily sanctified vocals over incessant and, at times, ecstatic balafon spellbound Malian society.

Neba Solo, as a young virtuoso, transformed people’s perception of the instrument by playing the balani, a high-pitched, portable balafon celebrated in his region of Sikasso. His popular anthem, “CAN 2002,” driven by an infectious four-to-the-floor House Music kick drum, pushed the balafon sound closer to hot-stepping ecstasy. Dedicated to the national football team in 2002, when Mali hosted the African Cup of Nations, it is an example of how youth culture, in all its intensity, thrusts itself into the wider culture.

“I am happy with where music has taken me.” DJ Sandji says as he leans against his stylish but beaten-up Mercedes, “I never travelled abroad with my talents, but it has brought me enough to keep my family and children happy.” He now runs a business renting out music equipment for weddings and parties. “As for the scene, there are not as many parties nowadays as there were. Between the fanatics, the bandits and kids on drugs –the energy of the movement in this city has changed.”

Back in Koulikoro after a couple of hours of intense dancing, Diaki takes the microphone and makes announcements to the village before the ‘show’ begins. Two young men take turns shouting into the microphone as they circle each other, pointing fingers in the air and creating a carnival-like atmosphere. They pluck a boy and a girl, both barely ten years old, and thrust them into the circle blindfolded to the sound of sirens and handclaps. What feels like a television game show begins to play out: the crowd hollers with delight as the children on all fours search frantically for a banknote. They are soon both completely covered in dust. Next, a line of village men take turns passing money to the DJs before showing off their dance moves. One flips and lands on his back to huge cheers, followed by a pair of identically dressed friends bucking and jolting their adrenalised bodies to the crowd. At 2am, Diaki takes over, setting off samples like rapid machine gun fire. His authority over the crowd is absolute.

Another of his apprentices, DJ Iba, takes control of the track selection, bringing spectacle with him. He throws himself to the ground as he plays and screams into the microphone, pushed and pulled by imaginary forces. Then, suddenly, he drops Bob Marley’s “Natural Mystic”, and everyone’s hands fly into the air: “Many more will have to suffer. Many more will die. Don’t ask me why.”

I put my arm around Iba. “When the men and women throw money at us, it is to honour what we do, and this is how we survive: bringing happiness,” he says. He explains how Diaki has taught him to blend three or four tracks at a time, and that he will continue to develop his own style. I ask Gladia what the future is for balani music. “Connecting with people will always be enough, but I want to make fast, hot music. Diaki has given us everything – even an education, which is why he is my idol.”

When the music is over, everyone has filtered away, and the equipment has been packed down, we head back in the jeep. I ask Diaki how such abandon is permitted in what feels like a highly conservative and religious culture. “How can you control the youth?” he says, nodding. “Life belongs to them. If they’re unhappy and leave, who will work in the field? The elders depend on them for everyone’s future together.”

We finally bump off the long track and are back on the tarmac at 4am, barely back to the real world. My lungs are heavy, and visions of electrified sinews still burn furiously through my mind.