Peu d’objets ont traversé l’histoire de la musique africaine comme les sandales en plastique. Nommées « lêkê » en Côte d’Ivoire, elles sont devenues dans les années 2010 l’emblème de la « Chine populaire », nom que se donnaient les fans de DJ Arafat, car ils étaient, pour reprendre les mots du défunt artiste : « aussi nombreux que les Chinois ». Au début des années 1990 déjà, elles étaient les chaussures des marches étudiantes et des premières heures du zouglou. Aujourd’hui, les stars du rap se les sont réappropriées, et la marque Gucci en a proposé sa propre déclinaison. Retour sur une histoire en musique et en images des sandales les plus célèbres du continent africain.

De l’Auvergne à l’Érythrée, une histoire africaine

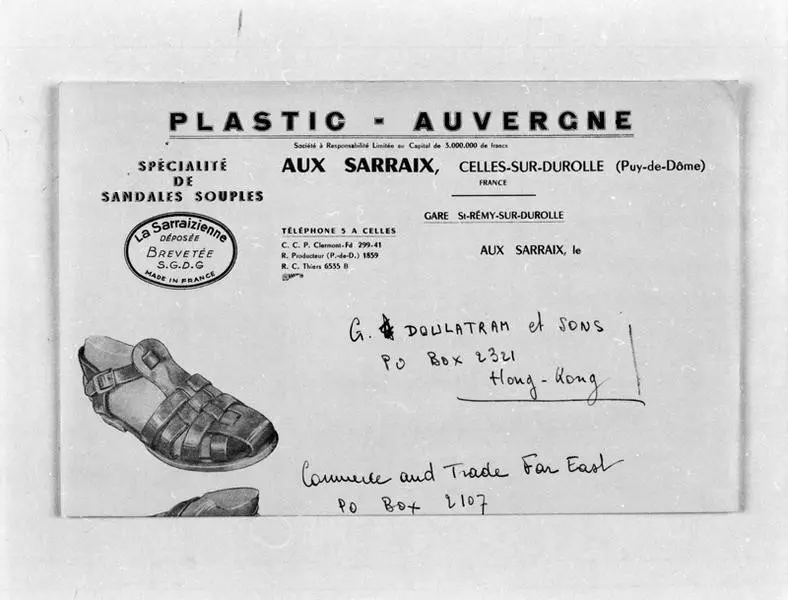

L’histoire commence dans un village dont le nom n’évoque sans doute rien aux lecteurs : le lieu-dit « Les Sarraix » dans le Puy-de-Dôme auvergnat, région rurale et montagneuse du centre de la France. C’est là qu’en 1946, Jean Dauphant, coutelier de métier, a dû faire face à un dilemme. Il venait de commander plusieurs palettes d’un nouveau produit qu’un commercial lui avait vendu pour enrouler le manche de ses couteaux, un plastique soi-disant révolutionnaire qui s’avéra finalement complètement inadapté à cette tâche : le PVC. Ne voulant pas perdre son investissement, Jean Dauphant eut l’idée d’utiliser ce plastique mou pour remplacer le cuir des sandales. D’abord appelé « sarraizienne » puis « plastic – auvergne », les sandales en plastique étaient nées, mais le produit ne rencontra qu’un succès très confidentiel à cette époque.

Florian Vallée, qui a enquêté durant trois ans sur ces sandales pour réaliser son film « L’Odyssée de la Sandale en Plastique : le destin extraordinaire d’un objet ordinaire », explique que c’est par l’intermédiaire d’une commerçante française installée à Dakar, originaire elle aussi d’Auvergne, que ces sandales vont s’exporter en Afrique, convaincue qu’elles peuvent y rencontrer du succès. Mais, contrairement à ses espoirs, les colons ne sont pas intéressés par ces chaussures, préférant les modèles en cuir. En revanche, les « nantis » locaux se les approprient car ils les trouvent pratiques et adaptées au climat. Dans les années 50, ce sont les chaussures des élites locales au Sénégal.

Dès la fin de la décennie, le constructeur Bata, déjà implanté sur le continent et sentant le vent des indépendances souffler – et un nouveau marché s’ouvrir -, décide de reproduire ces chaussures pour les distribuer à plus grande échelle aux Africains. En 1957, leur promotion se fera en musique, avec un morceau à la gloire de ce bout de plastique, enregistrée par le « grand maître » de la rumba congolaise qui devient l’ambassadeur de la marque : Franco Luambo de l’O.K Jazz.

Partout en Afrique, le modèle de Bata devient la chaussure de la petite bourgeoisie, propulsée par cette promotion d’une des plus grandes stars de l’époque. Mais à la fin des années 1970, les élites la délaissent pour des chaussures plus bourgeoises et Bata cesse de les produire, les usines ne pouvant plus concurrencer les producteurs locaux. Cela marque la fin de l’empire de la marque sur le continent.

La production locale continue cependant de se développer, mais la sandale perd de son aura et devient la chaussure des pauvres, sauf en Érythrée, où, durant les années 80, elle est la chaussure des combattants qui la fabriquent avec des pneus recyclés sur une unité de production clandestine. La chaussure est si populaire parmi eux qu’ils sont enterrés avec elle lorsqu’ils meurent au combat. Après l’accès à l’indépendance vis-à-vis de l’Ethiopie, les sandales deviennent un emblème national érythréen, encensé pas des poèmes, des fresques et des monuments.

Au même moment où ces sandales en plastique battent les montagnes aux pieds des combattants, c’est à l’autre bout de l’Afrique, en Côte d’Ivoire, que leur histoire musicale va se forger.

En Côte d’Ivoire : les lêkês, les marches et la « Chine populaire »

Si, dans les années 1980, Monique Seka se fait remarquer sur scène en portant un modèle de sandales en plastique à talons, toujours connu aujourd’hui sous le nom de « sekamania » en Côte d’Ivoire, c’est surtout à partir du début des années 1990 que les lêkê vont devenir un emblème musical d’un nouveau genre : le zouglou. Pour Pat Sako, le leader du groupe Espoir 2000 :

La lêkê d’abord c’est une chaussure qui, au moment des années 1980, était d’abord la moins chère. Elle était en caoutchouc, on pouvait l’avoir à vil prix. Et en 90 quand le zouglou est arrivé on en a fait une mode, on a vu même tonton Bouba [célèbre animateur ivoirien] qui avait des concepts de lêkê et tout, donc ils ont associé cette chaussure au zouglou. C’est comme ça que la lêkê est venue au zouglou, et qu’après les gens l’ont adoptée.

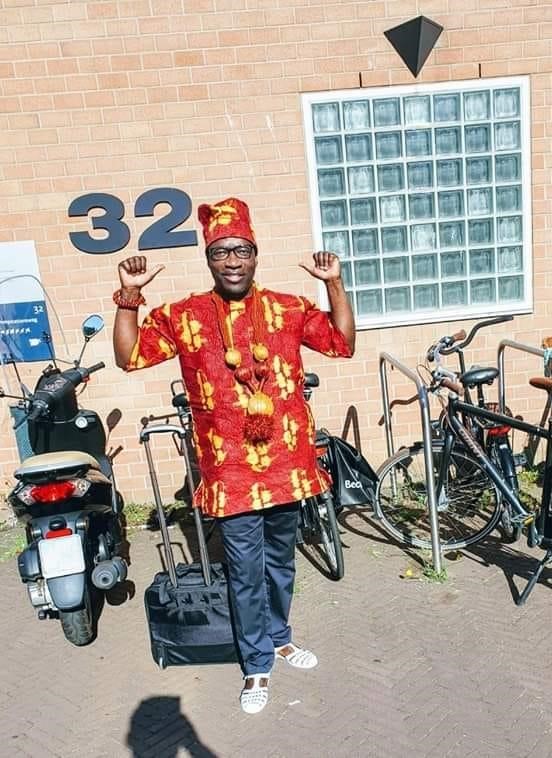

Comme l’explique Didier Bilé, considéré parmi les étudiants à l’origine du zouglou comme le « Z1 », le premier artiste du genre, le mouvement devient très vite populaire dans les bas quartiers d’Abidjan de Yopougon à Anoumabo, d’où vont émerger les plus célèbres artistes de leurs générations : Les Salopards, Yodé & Siro, Espoir 2000 et Magic System. Ces jeunes gens portaient alors des lêkê pour des raisons économiques, mais vont transformer ces sandales en objet de mode en s’affichant avec. Aujourd’hui encore, alors qu’il est devenu une star internationale, A’Salfo, le leader des Magic System, assume fièrement cet héritage.

Dans les années 2000, les lêkê vont également se politiser en Côte d’Ivoire car elles deviennent les chaussures des grandes marches patriotiques, ce mouvement de jeunes gens qui soutenaient le président en place Laurent Gbagbo face à la rébellion armée. On voit notamment les lêkê au pied du leader du mouvement, Charles Blé Goudé, grand amateur de zouglou auquel il emprunte le style. Lors de son procès à la Cour Pénale Internationale, durant lequel il sera acquitté, il se rend à son audience en… lêkê.

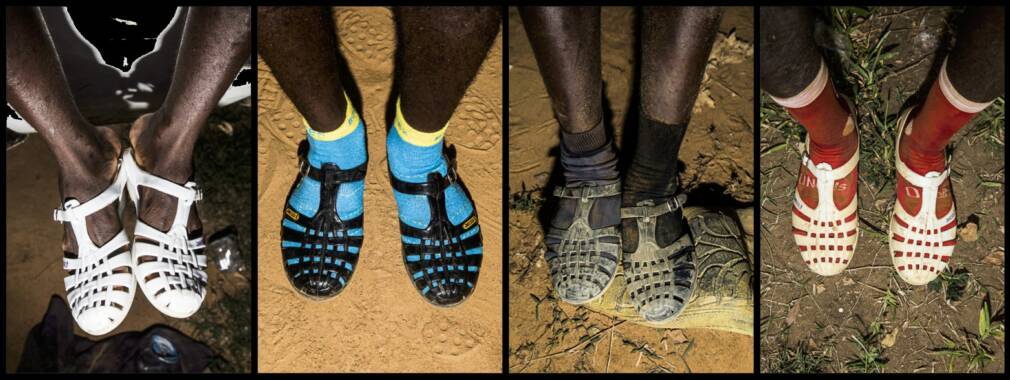

Au fil des années 2000, le mouvement zouglou s’essouffle quelque temps avec le succès immense du coupé-décalé, dont les premières stars préfèrent afficher ostensiblement des JM Weston ou des souliers de luxe italiens à leurs pieds. Mais c’était sans compter la montée en puissance du « Zeus d’Afrique », l’une des plus grandes star ivoirienne et d’Afrique francophone pendant près d’une décennie : DJ Arafat. Ce dernier, qui fréquente ardemment la rue princesse et ses cabines de DJ, dormant parfois à même le sol, a porté ces chaussures comme un emblème. La « Chine populaire », ses nombreux fans, se les sont réappropriées et les portent en toute occasion. Comme nous le raconte l’un d’entre eux, rencontré au marché d’Adjamé avec ses lêkê portées sur des chaussettes de sport :

C’est en mode chokoya. Ce qu’on appelle chokoya c’est-à-dire tu t’habilles bien, tu mets chaussettes. Au lieu de mettre crêpes-là [chaussure sebago], tu mets chaussettes blanches et lêkê blanc. Avec un jean serré, c’est la chaîne seulement qui manque pour faire Arafat.

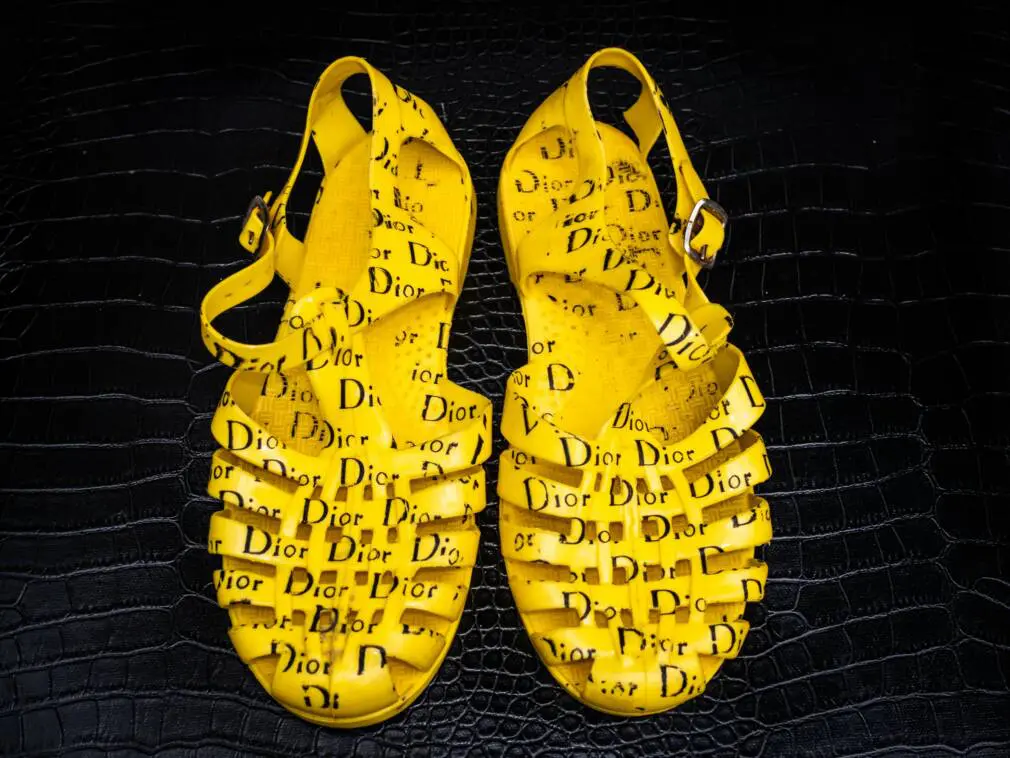

Face à cet engouement pour les lêkê, les constructeurs ne sont pas restés passifs et ont développé de nouvelles gammes qui se différencient à de légers détails telle que la position des boucles ou l’enchevêtrement des lanières, mais ils conservent un prix très faible, moins de 1000 Fcfa (1€50) la paire. Ils donnent aux lêkê le nom de personnalités : Boli, Drogba, Messi. Des contrefaçons arborent aussi les logos de grandes marques de streetwear, et les chaussures se déclinent dans de multiples coloris. Les lêkê sont portées autant pour aller travailler, jouer au foot et au maracana que pour sortir draguer ou se détendre, à chaque paire son utilité.

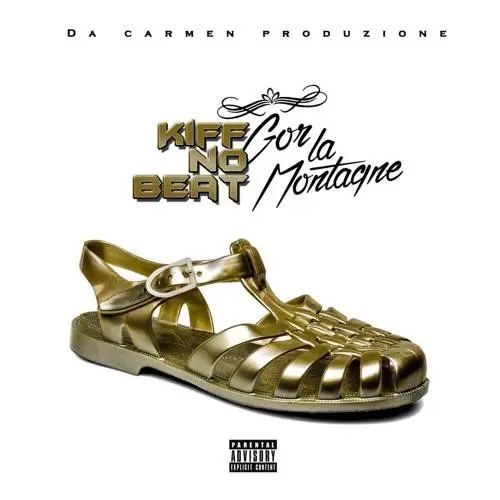

Aujourd’hui, la mode ne s’est pas tassée et ce sont les rappeurs qui se réapproprient ces chaussures. Les Kiff No Beat, qui ont lancé presque à eux seuls la mode du rap ivoire au début des années 2010, ont notamment choisi des lêkê dorées pour illustrer l’un de leur single, « Gor La Montagne », en hommage à l’un des pionniers du mouvement ziguéhi (les « gros bras » des années 1990).

Mosty, l’une des nouvelles sensations du rap ivoire, a consacré son premier « freestyle », en 2020, à ces chaussures. Du côté des personnalités, on ne compte plus ceux qui s’affichent en lêkê, du footballeur international ivoirien Didier Drogba à la star de la rumba congolaise Fally Ipupa, peut-être en hommage à son illustre ancêtre Franco Luambo ? En tout cas, Fally Ipupa ne porte pas le modèle Bata promu par son illustre prédécesseur, il y a préféré une déclinaison quelque peu plus luxueuse, des lêkê produites par… Gucci, prix : 450€ (300 000 Fcfa).