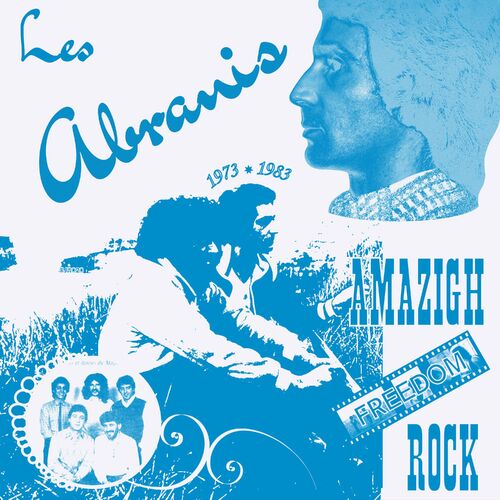

Cult. No word could be more appropriate when referring to Les Abranis, a group revered by sound seekers the world over as much as by the proselytizing zealots of Berber identity. To measure their impact, you only need to stroll across the vast web, where these musicians from Algeria are the subject of many conversations, just as their vinyl records – 45s and LPs – are extremely popular on digger networks. And this hasn’t been the case for a long time, even if a compilation published by the Swiss label Bongo Joe has once again put the spotlight on this legendary combo. How do you explain such a phenomenon that spans the ages? “There’s no doubt a feeling of nostalgia for the new generation born in Europe, who are curious about what we represent. Back then, we embodied the symbiosis between Europe and the Kabyle world. We were at the height of the cultural openness that dominated the world,” says Shamy, co-founder of the group that will celebrate its eightieth birthday next year.

“We were even the first at Sacem (Society of Authors Composers and Musicians) to produce scopitones (jukeboxes combining image and sound, editor’s note). Ahead of Johnny and Claude François!” assures the same man, author of numerous documentaries and books. It was no small feat for this group, born in the minds of two young Kabyles who had emigrated to France, where they frequented the Kabylian bars that made up the hot nights of north-eastern Paris, while listening to the music of their youth: Elvis Presley, James Brown, Otis Redding, Duke Ellington, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and so on. A non-exhaustive list, of which the future octogenarian likes to specify that Cat Stevens was his favorite singer.

Ambassadors of the “Rockabylie”

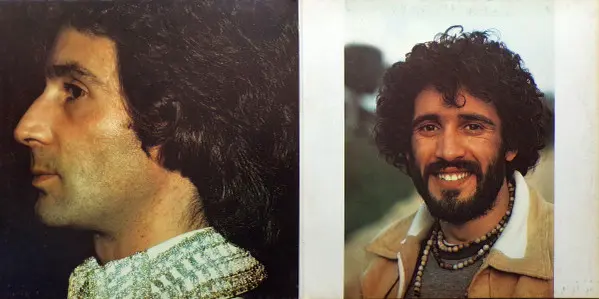

It all began in 1967, when two young people decided to form a rock band. The first, Abdelkader Chemini, born in 1944 and better known by his nickname Shamy El Baz, arrived in France in the early 1960s, having been tortured in the djebel by the French army. There, he underwent 33 operations, forever bearing the scars of this war which at the time did not have a name, but he turned this resilience into a new opportunity: he seized the opportunity to go back to school as a self-taught student and learn the first rudiments of keyboarding. “I quickly understood the difference between people and power. They’re two very different things,” insists the man who has lived in France for sixty years, now dividing his time between Honfleur and Paris, in 2023. As for the second and youngest Karim Abdenour, Sid Mohand Tahar by birth, he arrived in France at the age of thirteen, just after the Evian Agreements sealed Algeria’s independence. Far from his native mountains, the man who picked up his first guitar when he arrived on the banks of the Seine would soon be frequenting the Golf Drouot (a rock club in Paris, editor’s note), where he found inspiration for an original version of rock, “rockabyle”. Les Abranis, a band of young people among so many at a time when the planet was rustling with hippie effervescence, an era of flowery revolutions in peace and love mode.

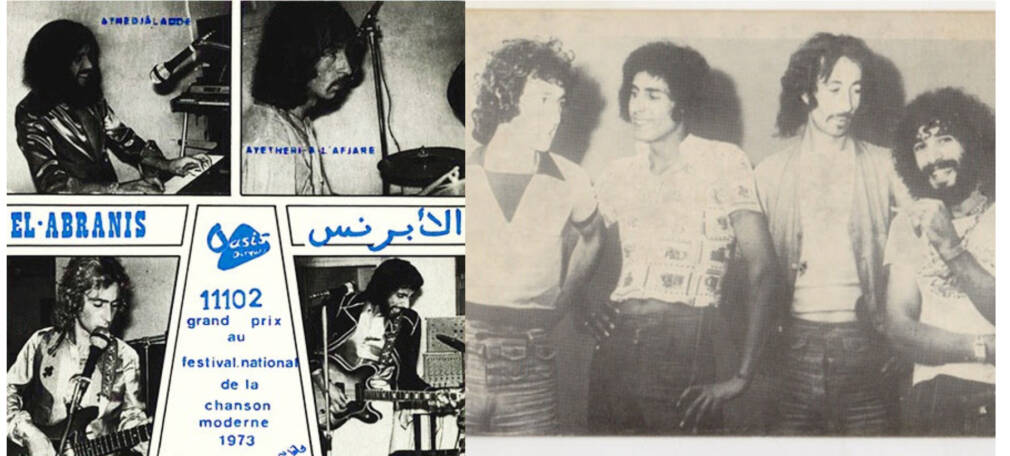

Les Abranis, a name that owes nothing to chance for this abrasive formation. “For centuries, three Berber tribes covered an area stretching from Egypt to Mauritania. Two were constantly at war with each other, while the third was considered more pacifist. They were the Branis, who acted as reconcilers”, assures Shamy, who recognizes in this choice a form of “allegory regarding their objectives”. From a musical point of view, these ideas were to formulate a link between the folklore of their origins and the sounds that cross the world, a fusion they formulated in 1973 with drummer Samir Chabane and guitarist Madi Mahdi. The 45-turn “Athedjaladde”, which introduces the present Amazigh Freedom Rock compilation, is a solid representation of this. “Ayetheri A L’Afjare”, another song recorded in 1973, is another example of this feeling of formal freedom, where the general tone – garage rock tinged with post-psychedelia – does not preclude the daring use of pentatonic rhythms.

The longhairs that irritate the FLN

They also write their lyrics in the middle ground. What are they about? “Social, philosophical, festive, sentimental, sometimes rebellious and demanding…“, Karim, the singer and main composer, points out today. “The lyrics were less crude than Matoub Lounès,” moderates Shamy. “We were inspired by the Kabyle authors of the 18th century and the modernity of our time.” And this synthesis took the form of metaphors and parables, which hint at the situation of the Amazigh people in post-colonial Algeria. The significance of this, however, can be quickly understood by all, judging by the echo their songs provoke in the mountains of North Africa. In any case, their avoidance of head-on confrontation with the government in Algiers didn’t prevent them from getting into serious trouble when, driving from Chelles in the Paris suburbs, they arrived in Algeria for the first Festival de la Chanson Algérienne in 1973.

“Algerian officials were afraid we’d sing in French or English. In fact, when we started singing in Kabyle, they quickly understood: after three songs, they pulled down the curtain!” recalls Shamy, half-amused, half-ironic, whose passport was then taken away from him for six months. Clearly, the authorities in Algiers put serious pressure on the group to sing in Arabic, which they did, not without “derision”, by composing a song with three verses – one in Arabic, one in French, one in Kabyle – and then signing the soundtrack to a film, with the explicit title (Les Etrangers). “The Arab-Baassist authorities saw our arrival as the intrusion of a parasite. They felt that our style was a bad example for young people. What bothered them most was that our lyrics were sung in Kabyle, a language that was despised and virtually forbidden,” Karim continues. “For the Algerian authorities, we were seen as decadents, carrying the seeds of capitalism,” adds Shamy. And so, naturally, it was a double whammy for this group of free-spirited hirsutes, who were threatening the values of the nation-state as it was being built. President Boumediène went so far as to bring together four ministers to discuss the problem of this group, which was filling the stadiums by importing ideologies contrary to the spirit of the FLN.

“We simply wanted to dig up what the authorities were trying to bury,” Shamy makes clear, as he likes to say, Saint Augustin was Berber, and that nine popes were Kabyle. From then on, the Abranis were at the forefront of the Amazigh cultural revival movement. “And then there was Djamel Allam, Idir…” adds Shamy, listing the insurrectionary movements linked to this community. “The Spring of ’80, the 1988 movement, 2001 and the Black Spring on which I made a film, all came from Kabylia. And even the hirak took up our slogans.” It’s easy to understand why, in 1975, the band’s first major tour of Algeria was banned from performing in Kabylia, provoking demonstrations and clashes with the local police, who eventually authorized the show to calm things down. “Our fans were even jostled and beaten, arrested and mistreated, even tortured, notably in Sidi-Aich during a gala canceled by the police at the last minute,” Karim explains. He adds that they were subsequently censored by the official radio and television.

“A perpetual creative laboratory”

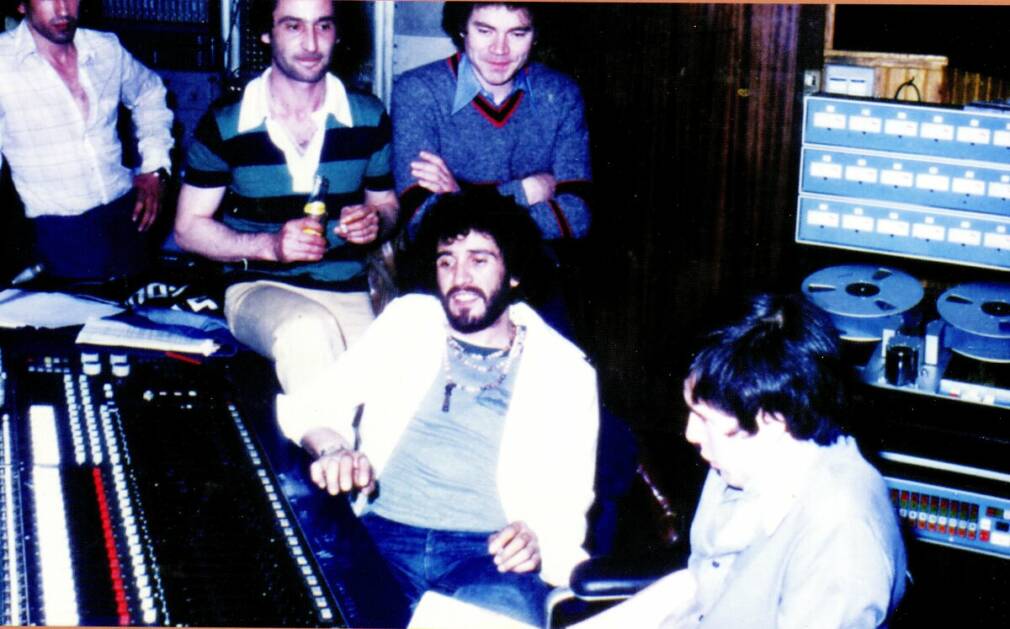

Just as the aesthetic of these musicians changed over the years, as they gradually added strings and chords to their playing, the combo underwent a number of personnel changes, following the departure in 1975 of the first pillars, Samir Chabane and Madi Mahdi. The albums Les Abranis recorded included exiles from Algeria as well as musicians from the French scene, including bassist Jannick Top and drummer Dédé Ceccarelli. These additions in no way detracted from the original character of the group, which was founded on Shamy and Karim’s compositions, “an improvised yogurt base from which all our references emerged. (…) It was a perpetual creative laboratory. Unlike others who have modernized the traditional, such as Nass El Ghiwane, or Vigon, who sang in English,” explains Shamy, one of the most erudite when it comes to evoking the spread of Kabyle culture through the ages. “We even used Breton instruments! It goes all the way back to Hannibal.”

The pioneering and singular character of Les Abranis, used as they are to José Artur’s Pop Club, but shunned by most of the mainstream media – “Apart from a few Maisons de la Culture, it was mainly associations who asked us to do free solidarity galas, because they themselves were penniless,” recalls Karim – is evident in every second of this compilation, which draws on their abundant discography recorded between 1973 and 1983, their golden age which culminated in the amusingly and aptly-named Album N°1. From the mid-1980s onwards, the band continued to tour, both in North Africa and Europe, even opening for Les Négresses Vertes and La Mano Negra in Germany, but only occasionally in the studio. The dark days of Abranis 77, released on Bordj El Fen, an Algerian label, are long gone. Imitated by Tayri in 1978, which was far more festive in tone.

Twenty years after their first grooves, Shamy El Baz and Karim Abdenour went into the studio in 1993 to produce a new album in Algeria on their own dime, just as the country had entered the black decade that was to decimate the entire local culture. This was to be the final act, as the two lifelong friends – “to this day”, Shamy insists – were at odds. “Karim agreed to sing for Algiers, Capital of Arab Culture. I didn’t!” recalls the elder Shamy vehemently. And it would be more than ten years before a new formula of the group reappeared, with Karim, now retired and settled in Algeria, but also some of his children, including Belaïd on guitar. “Abranis has become more of a concept than a group based on a few individuals. A good forty musicians, including guitarists, drummers and bassists, made an appearance in this adventure,” Karim points out.

A concept that’s still alive and kicking, “with lots of projects for studio compositions and music videos,” according to the latter, who has publicly announced his retirement from the scene. Yet it’s hard to imagine an artistic descendant for these strange UFOs, who appeared on the recording scene half a century ago, despite the uproar caused by their countless concerts in Algeria to packed stadiums. Of course, listening to Shamy, Khaled would have said that the Abranis had given him the idea of doing something “modern”, but it would be difficult to see the Raï singers as heirs to these pioneers. If anything, it would be at the other end of Africa’s largest country that musicians are following in the footsteps of the Abranis. The Tinariwen and all the followers of desert blues, the Tamasheq sound that asserts an identity at odds with the central state. “Their approach is the same, in look as in lyrics, and like us they use guitars full of rock and blues.“