“It was like a mass! It was madness: the audience loved it!” enthuses Jako Maron about the historic reformation of the Force Indigène collective, who made their mark on Réunion Island with the first electronic hip-hop album in 2004. Blending Pei percussion, hip-hop beats, jungle swings, 360° samples and electronic textures, produced and arranged by a Jako Maron who was inspired by the sound of Dead Prez, Z’Amalgame has just been remastered and reissued on vinyl to celebrate the crew’s twentieth anniversary. The group was also invited to perform last October on stage at Les Électropicales, the island’s unmissable electronic music festival.

“People knew Franky Lauret and Babou B’Jalah’s lyrics by heart: Z’Amalgame is the sound of their youth,” he adds with the pride of one who seems to have suffered from a lack of recognition. “It moved me to play this repertoire on an official podium, a truly beautiful stage where, for once, people knew my work. At the time and for a long time, I remained an underground guy.“

The Nyege Nyege tribe

Their partnership came to fruition in 2018, when Nyege Nyege Tapes published The Electro Maloya Experiments of Jako Maron, a compilation that brings together ten years of research and experimentation. In his studio-laboratory, the producer set out to dissect and reconstruct the rhythmic DNA of maloya, the emblematic music of Reunion Island.

In Jako Maron’s hands, maloya, the ternary blues inherited from the island’s former slaves and totem to Reunion’s creolité, is propelled into the future with the help of modular synthesizers. Sati, pikèr, kayamb, roulèr… On his machines, the incandescent pulse of traditional maloya percussion is reinvented, with a rave and acid trance addition and a clear objective: dance. It’s not the first, but this album reveals the audacity of the producer who, at the age of fifty, is finally attracting the interest of the (inter)national press and peers, notably the British genius Aphex Twin, who mixed one of his tracks live the following year.

“Before I met Nyege Nyege, I found it hard to believe in myself. I felt like an alien all alone in his saucer with my tinkering and modular synths,” admits Jako. “But they trusted me, they took me seriously, and thanks to them, I exist. They pushed me to experiment further and be who I am. Now I know that what I’m doing is real music. That’s huge for me, it changes everything. When I went to play at the Nyege Nyege Festival in Uganda, I also met all the artists in the crew: it opened up my chakras (laughs) and I realized that there are tons of aliens on Earth. I’d finally found my tribe, and that felt really good!”

The voice of the bobre

In recent years, the producer has kept busy. When he’s not touring the world with the extra-terrestrial troupe, Jako Maron keeps his island in mind and composes less technoid repertoires “more accessible to the Reunionese public” by teaming up with local artists. Alongside poet Axel Sautron and percussionist Zan Amemoutou-Laope, the grandson of legendary ségatier Maxime Laope, Jako Maron released his 2022 album Kabar Jako, a project where the sound of machines rubs shoulders with the lamenting fonnkèr and the organic power of percussion. On stage, the trio pays tribute to the jubilation of kabar maloya, a festive, public celebration that must be distinguished from servis kabaré, the ceremony of ancestor worship whose song and dance ritual is reserved for the initiated. And it’s precisely this spiritual dimension that Jako Maron explores on his new album, Mahavélouz, unveiled in early February on Nyege Nyege Tapes.

This time, Jako Maron uses the only melodic instrument of maloya, the bobre, a musical bow related to the Malagasy jejy voatavo and the Brazilian berimbau. “The bobre is an integral part of the ritual, its hypnotic vibrations unifies energies and prepares for the arrival of the spirits. The sound of the bobre is mystical and has always enchanted me. For me, it’s the soul of maloya,” explains the producer. “I don’t believe in any god, I’m not religious, but I have a deep respect for this cult and the people who perpetuate it, because they honor the memory of our ancestors. In La Réunion, these ceremonies, this oral transmission, are all that’s left to the descendants of slaves. My real name is Jackie Thiburce and Thiburce is a slave name, but I know nothing about my ancestors. Our history isn’t written in books.“

Sampled from a series of traditional melodic phrases, distorted, carried by feverish riffs, boosted with filters and effects, in Mahavélouz, the bobre stands up to the obstinate bass of a resolutely techno electronic kick. “In maloya – unless it’s amplified, as with Zanmari Baré – the bobre is often buried by the percussion, and I wanted his voice to be heard. My music doesn’t need words, but the bobre’s voice is powerful, it’s ancestral but it’s topical and it has things to say. It’s a word of union, revolt, revolution and resistance against oppression. I set the tone right from the first track on the album: ‘Paré pou saviré’, a call to rise up, to collectively overthrow what seems unjust to us. Maloya is a vessel that unites people and uplifts souls.” Though Jako pays homage to the Reunionese flag, the famous mahaveli, in the title of his latest opus, he is far from having grown up in the political, identity-based and protest-oriented world of maloya.

Clandestine maloya

Born in 1968 in Saint-Denis de La Réunion, Jako Maron first grew up listening to the music of his grandparents: Tino Rossi, the sega of the Kaloupilé troupe or the nursery rhymes of Jacqueline Farreyrol, which his teacher/aunt adored. “In my family, we were not at all aware of maloya,” recalls Jako. And with good reason: denunciations, gendarmerie raids, arrests, confiscation of instruments, forbidden gatherings, pressure and repression… Until the 1980s, maloya was the “bête noire” of the Reunionese authorities – especially the Gaullist deputy Michel Debré – because it simultaneously recalled the slavery and colonial past of Bourbon Island, and also brought together militants of the Reunion Communist Party founded by Paul Vergès in 1959. In a major interview (now unavailable) published in 2019 by the Qwest TV platform, the famous maloyèr Danyèl Waro tells the story.

“The political authorities and the church considered maloya to be the music of the poor, the Africans, the less than nothings. For them, the drum was the devil, and ceremonies paying homage to the ancestors were considered witchcraft, archaic celebrations. The maloya ban was a human ban inherited from slavery. But in reality, they repressed and stigmatized maloya because they were afraid of it. Hidden because rejected, maloya belonged to the underworld, it was highly subversive. I’m talking about a time when you really had to fight for maloya to exist.”

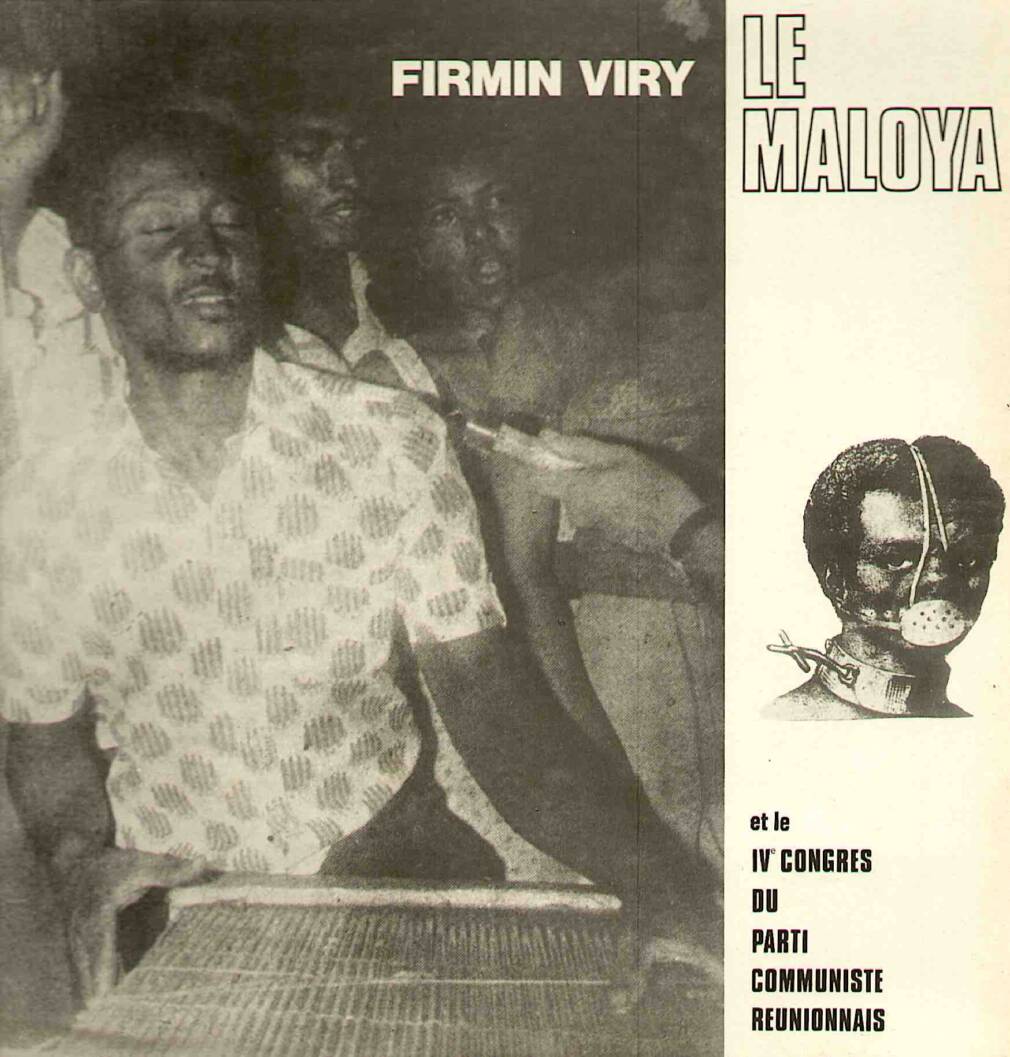

Many testimonies agree that maloya was rejected even within the Afrodescendant community because it reminded the descendants of slaves too much of their Africaness and traumatic past. Against this backdrop, it’s hardly surprising that Jako Maron, like many Reunion Islanders at the time, was a stranger to maloya, which was mostly transmitted in the privacy of families or at Communist Party rallies, often carried by the extraordinary Firmin Viry, whose voice and family troupe electrified the crowds. Jako Maron remembers the first time he saw Danyèl Waro on television. “There was only one black-and-white channel, it was on the regional news. Danyèl Waro was very young, and we were sitting on the couch with my grandparents, thinking, ‘What the hell is this?’ We must have laughed like nasty people. At the time, I didn’t understand a thing.” But it wouldn’t last.

The epiphany

As a teenager, Jako Maron listened incessantly to a cassette by Jean-Michel Jarre, Équinoxe, but also to the pioneering electro of the Greek Vangelis and the new beat of Belgians Front 242. His uncle had an organ, one of his buddies, a synth. When he spent a school year at IUT in Dijon, trying to become a computer scientist, the future producer spent all his time at the FNAC. The object of his desire? A Yamaha DX7 synthesizer. “There were three or four of us geeks and we queued up to take turns playing. I was all about new wave back then!” he recalls. “I loved music, but I still didn’t have any plans to make it, let alone the means.” Meanwhile, the election of François Mitterrand in 1981, followed by that of Communist Paul Vergès to the Reunion Regional Council two years later, rehabilitated maloya in the public arena and contributed to a change in mentality.

Firmin Viry, Lo Rwa Kaf, Gramoun Lélé, Gramoun Baba, then Danyèl Waro, Troupe Flamboyan, Françoise Guimbert and the Voulvoul group…Thanks to these stubborn musicians and activists, the beating heart of the roulèr resonates throughout the island, and maloya continues to support the struggles of the Reunionese people who are calling for the island’s autonomy and the teaching of Creole in schools. A genre of struggle and rebellion, the maloya of those years also denounced post-colonial injustices, the socio-environmental abuses of sugarcane monoculture, and political scandals. Notably that of Bumidom – for Bureau pour le Développement des Migrations dans les Départements d’Outre-Mer – which, under the impetus of Michel Debré, conducted sterilization campaigns, forced abortions, and child displacement from 1963 to 1981. In 1980, the group Ziskakan denounced the injustice in their song “Bumidom”. Maloya gradually made its way onto the airwaves, leaving its mark on a whole new generation of artists and activists.

For Jako Maron, the epiphany came when he returned to Réunion Island for his military service. “I was 21 years old. On the way to the north of the island, in the army truck, the guys were singing maloya, especially Danyèl Waro, and that really impressed me. I became aware of the power of maloya, of its ability to unite, to uplift. The power of maloya touched me deeply. I understood the importance and place it held among the people of Reunion. And I realized that back home, we’d missed out on it. After that, I immersed myself in it. I listened to Danyèl Waro over and over again, going to his concerts. I had a cassette of Firmin Viry too, and I loved the grain of Simon Lagarrigue’s voice that accompanied him. It went with everything I loved about blues, funk, dub… music whose impact is based on rhythm. At that point, from a maloya perspective, everything started to align for me. I wanted to start sampling. But at first, it was hard to find maloya vinyls in the stores on Réunion Island.”

Failing that, Jako Maron sampled sega, notably that of violinist Luc Donat, for the interludes on Nana 7 i M, the only album released in 1996 by his very first group, Ragga Force Filament. By saving money, the producer managed to buy a Casio SK1 and sampled all the records he borrowed from the media library: dub, dancehall, rock, punk, classical music, jazz, jungle, trip-hop… Everything fed the ears of this curious music lover who, little by little, asserted himself as a true musician.

Modular revolution

Jako Maron’s second revolution came in 2012, the year he bought his first modular synthesizer during a trip to Paris. “I bought a few modules, some rails, and came back to La Réunion, where I made the box out of an old toolbox!” recalls the producer, who was no stranger to electro-artisanal tinkering. Some time earlier, Jako Maron had already acquired a cheap keytar whose Frankenstein-like belly he opened to extract ultra-experimental tracks from its electrical circuits, leading him to Saint Extension, his very first solo album unveiled in 2009. Coincidentally, this was the same year that UNESCO named maloya an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In any case, the mutating, almost supernatural oscillations of the modular synthesizer, mark a definitive turning point for the visionary, who found his sound, his signature.

Almost fifteen years later, Jako Maron is no longer the lonely alien he once was. Boogzbrown, Do Moon, Cubenx, Agnesca, Sheitan Brothers, Labelle, Loya… In 2018, the Digital Kabar compilation testifies to a very dynamic scene – largely dominated by men, as in traditional maloya – that uses its machines to propose innovative reinterpretations of Réunion’s musical heritage, and particularly, maloya. Since then, Reunion’s electronic music scene has opened up to women, with the likes of Kaloune, Maya Kamaty and Eat My Butterfly making regular appearances on French stages and in Électropicale’s line-up. “Every time there’s a new face on the Reunionese electronic scene, I’m very curious. I listen to everyone and I always hope I’ll get a slap in the face. That’s how we move forward. It’s a healthy emulation,” asserts Jako. “For example, I really admire and respect Loya’s work. He’s very strong and that makes me want to go right back into the studio and get back to music. It motivates me. It makes me want to surpass myself.” Released at the end of 2024, Loya’s new album sets the bar very high indeed: conceived in collaboration with the Remanindry family of the Antandroy people, a shamanic community in southern Madagascar, Blakaz Antandroy invokes the “Kukulamp” spirits with a blend of electronic trance, lokanga zither and healing chants.

Digital Kabar’s tracklist also includes the vintage sound of a Moog keyboard in “Kom Lé Long”, a track by Ti Fock, whose militant reggae-rock maloya made its mark at the turn of the 80s in La Réunion and beyond. As elsewhere, the great (r)evolutions in music writ large have left their mark locally. Gilbert Pounia with Ziskakan, Alain Peters, René Lacaille and Loy Erlich with Caméléon, Jean-Claude Viadère… In the 70s and 80s, the avant-garde of Réunionese musicians began to explore new horizons, a highly creative period that saw a new generation of artists electrify sega and maloya, reinventing it with a psychedelic twist. Studios like Piros and Studio Royal in Saint-Joseph, which until then had shunned maloya in favor of sega and variété, gradually opened up to these young, long-haired musicians. Published in 2017 by Strut Records, the must-have compilation Oté Maloya (The Birth Of Electric Maloya On Reunion Island 1975-1986) offers a deep dive into this exciting golden age. And what about today?

Maloya is not dead

“Today, you can find maloya in mainstream Reunionese music, rap and even trap!” exclaims Jako Maron. “After all, why not? Basically, it’s great that maloya resonates all over the island and touches everyone. But I wouldn’t want maloya to lose its soul either, to be devitalized for purely commercial purposes. Mind you, the guys do it well, their trap follows in the footsteps of the roulèr, the hi-hats are in ternary… But their music isn’t a protest. At the very least, it shows that these young artists are aware of maloya and therefore part of its history.”

In 2014, Réunionese Creole officially acquired the status of regional language, enabling it to be taught in schools and studied at the University of La Réunion. Can we make the connection with the way maloya and its history seem to be once again a proud lever of identity for the Creole community on La Réunion? Perhaps, yes. Achem, Jahiro, Nairod, Alex Sorres, Di Panda… In any case, many of the island’s rappers are carrying the flame. In 2023, a landmark album was released: M.I.N.D (Maloya Is Not Dead), imagined and conceived by Reunionese producer Nicolas M’Tima aka Nikooo Prod, who has already made a name for himself in mainland France by composing tracks for Vitaa, Black M and Maître Gim’s. The M.I.N.D concept is a first for Réunion Island. The album brings together some of the most important voices on Réunion’s urban music scene, as well as pillars of the contemporary maloya scene such as Simangavole, Votia, Les Tambours Sacrés, Davy Sicard, Zanmari Baré and Lindigo. From one track to the next, alcoholism, domestic violence, and other topical issues intersect in Creole with the historical subjects of maloya songs, notably in the track “Ten’ Fénwar” where the group Kiltir and rapper H Magnum (French of Ivorian origin, but with 182K followers) revisit the history of Reunionese maroons – i.e. the rebellion of slaves who fled the plantations to establish themselves in autonomous communities in the hard-to-reach highlands of the island.

Live rituals

“Jako Maron is my chosen name, my identity, my vindication. It’s my way of inhabiting my history and my creole identity,” explains the producer, who has put up a poster of the 1992 Fèt Kaf, a day of homage to ancestors as much as a popular festival celebrating the abolition of slavery on December 20, 1848, on his studio door. Swiveling in his armchair, Jako Maron turns his webcam on his machines, which he displays with geeky tenderness. “I’m waiting to receive a new warp drive, a giant, magnificent thing. For me, each new tool represents a new avenue of sonic exploration. Who knows what I’ll do with it?” he enthuses when discussing his future projects. Often asked to produce remixes, Jako Maron now has the luxury of choosing to work on what he really likes.

Soon, his machines will be back in the clubs, spreading Mahavélouz‘s repertoire internationally. “Live is my electronic ritual, it’s like a ceremony that I always start with a great moment of purification with a very violent, very slow distortion track, which then leads into dance tracks. When I play in Germany, for example, people are carried away by the rave energy, even if they don’t know maloya. When I play in Brazil, Mozambique or Uganda, people recognize the similarities in rhythm, identity and spirituality. But in every case, people are touched because they hear the sacred.” Not surprising for the man whose avatar is Jako Malbar, a mystical figure in Tamil culture, charged with warding off evil spirits and bringing good luck. With all the omens on his side, Jako Maron’s future is set to shine.

Mahavélouz by Jako Maron out now on Nyege Nyege Tapes