For the artist from Salvador de Bahia, the ties to Africa have always been one of the driving forces behind his creative process and his political commitment. PAM focuses on this fruitful long-term relationship. Listen to the associated playlist on Getup.

Erected for 50,000 people from all over the world, the Festac 77 buildings were reminiscent of BNH social housing in Salvador de Bahia, with its cramped apartments constructed at the beginning of the 1960s to lodge the inhabitants of the favelas. This, at least, was the impression made on the singer and composer from Bahia, Gilberto Gil, when he arrived in Lagos in 1977 to represent Brazil at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts. This observation, point of departure for the artist’s reflection on Black culture in an urban setting, influenced Gilberto Gil’s work for the decades to come.

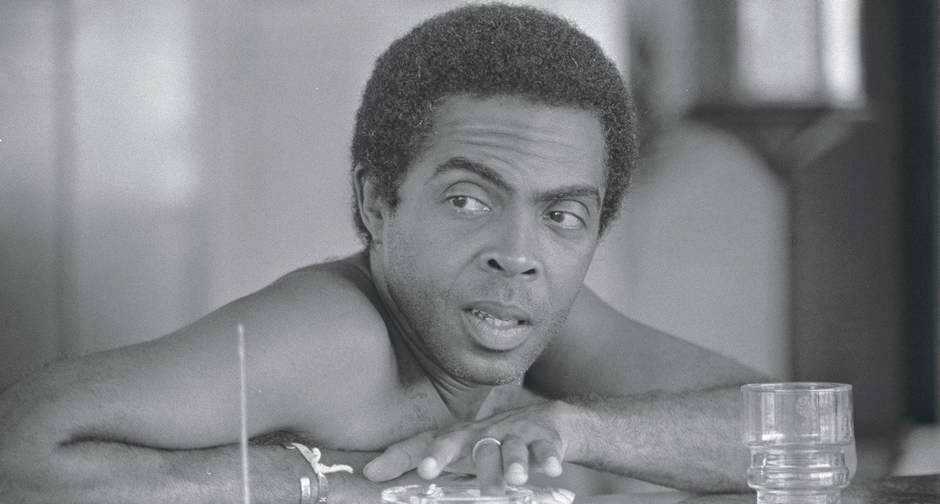

Already called Gil when he launched his career at the beginning of the 1960s, he described a rural world with subtlety, but did not seem to be particularly preoccupied with social issues. After his birth in Salvador in 1942, his family had returned to live in Ituaçu, a small village in the sertão, where he soon showed interest in learning the accordion. The son of a doctor and a teacher, the young Gilberto Passos Gil Moreira did not endure racism or discrimination during his childhood. It is only when he became famous nationally that Gil started to comment on Negritude, first by using the instrument typically associated with capoeira dancing, the berimbau, in the song Domingo no parque. Performed live on TV Record with the group Os Mutantes and with an arrangement by Rogério Duprat, the song came in second at the Third Sao Paulo Popular Song Festival in 1967.

Tropicalia, Exile, and Black Awareness

Three years after the military coup d’état, the question of inequality, racism, violence, and civil liberties began to shake up Brazilian society. Boosted by the popularity of the major festivals, the MPB movement – Música Popular Brasileira – in full effervescence, was searching for a new identity. The result was Tropicalia, spearheaded by Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso. Friends both on and off the stage from the beginning of their careers, the two companions shared the same aesthetic conception of pop music. Along with Tom Zé and Os Mustantes, they made the fusion of traditional rhythms and psychedelic sounds the musical manifesto of two intense years of protests against the dictatorship, up to their arrest in 1968 under the pretext of a lack of respect towards the national anthem, and their exile to England the following year.

In London Gilberto Gil went to museums, art galleries, recorded an acoustic album and made friends with counterculture personalities. Along with musicians from Hawkwind, he helped to organize the Ashtonbury Festival. A huge fan of British rock, he followed the careers of the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix, from whom he learned precision and economy of means, was excited by Tyrannosaurus Rex, Pink Floyd and The Incredible String Band. This is also where he discovered reggae. In 1971, the Caribbean scene in Notting Hill, embodied by Jimmy Cliff, Burning Spear and Bob Marley, was exploding. “I was fascinated by Rasta culture,” he later said. “This helped me to identify what was African in Brazilian culture.”

In England, Gilberto Gil became truly aware of the weight of the problem of racial identity in the world, be it through the civil rights movement in America or the news coming from the African liberation movements. In this global context of the rediscovery and valorization of Negritude, Gil, who started sporting an afro and wearing Black Power clothing, now strove to understand what it meant to be black in a society that denied blacks any historical or cultural individuality. On his return home from exile in 1972, one of his first acts was to parade with the Afoxé Filhos De Gandhi, keepers of the memory of the carnival of the city of Salvador and followers of the candomblé religion, in order to fight the ostracism it suffered from. Recorded the following year, Filhos de Gandhi evoked the orixás, the entities that connect man with his spirituality, before becoming in 1975 the bravura piece on the double-album Ogum, Xangô that he improvised during jam sessions with Jorge Ben.

Gilberto Gil learned a great deal from English pop and returned to Brazil with the firm intention to refresh Brazilian music; but in 1975 his vision of Negritude was still associated more with the tribal aspect of batuque, which symbolizes the traditional side of African culture, rather than hardline struggle. The artist needed above all to regenerate himself, to return to his roots, to evacuate the violence of the dictatorship that had forced him into exile. This return to the basics resulted in the album Refazenda, ode to nature and the slow pace and gentleness of life in the countryside. Refazenda blends sophisticated pop with rhythms from the Nordeste and proclaims a softer version of the Tropicalism that had been interrupted by exile (a play on words between fazenda, the farm, and refazendo, to redo).

African Boomerang

The success of Refazenda could have led the artist to believe that he had found his chosen path, but two years later in Lagos, where the political questions raised by the Black diaspora and revolutionary movements such as the Black Panthers were agitating the Festac 77, Gilberto suddenly found himself confronted up-close with African pop music: High Life, Juju Music and above all Afrobeat. Fela, in fact, through his music and his Pan-African militancy, was to have a major aesthetic, artistic and political influence on the career of the man from Bahia. Thanks to this discovery of an engaged, modern, thriving and powerful Africa, Gil was now driven to re-evaluate both his own African roots and the importance of this ancestry in Brazilian civilization, centered around two territories: the farms and the favelas.

Refavela, a social critique and a political instrument serving the Black community. The omnipresent percussion, the strong rhythms, the expressions of African origin, the elements of the candomblé cult and the references to the Black Rio movement left no doubt as to the artist’s intentions: to express the power and the richness of his Black culture. An approach that was not always well received in a country where there was still an official status quo concerning the question of racism fabricated by the military regime still in power and denounced by the new MNY movement (Unified Black Movement), launched in Sao Paulo in 1978 in reaction to the death of a Black worker in a police station and to the expulsion of four Black athletes from a sports club in the capital city.

This challenging of official history was also the focus of the following album, which concluded the quartet of albums starting with Re in the title: Realce, where he paid tribute to Bob Marley by adapting into Portuguese the global hit No woman no cry, which also became his biggest commercial success. Gil promoted Afro multi-ethnicity as a symbol of Negritude in Brazil and emphasized the significance of the ethnic, Indian, African and European differences that contributed to founding a “Brazilian culture”. With Quilombo (1983), the soundtrack to the film by Cacá Diegues telling the story of the 17th century slave Zumbi’s fight for freedom , Gil explored the memory of the Afro descendants and the foundations of their common identity. Composed with the poet Waly Salomão, Quilombo, O Eldorado Negro describes the small, mythical autonomous colony Palmares as a possible new utopia.

Art and Politics, Same Struggles

The question of memory and Black identity in Brazil became central to Gil’s political activism. In 1979 he became a member of the Bahia Regional Cultural Council, land of arrival of the first Bantu and Jêje-Nagôs slaves. In 1987, in his native city of Salvador which was then at the height of “Re-Africanization”, he was elected city councillor on the PMDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party) ticket and became president of the Gregório de Matos Foundation. Relegated to the post of Culture Councillor when he sought to become mayor, he quit the PMDB and joined the Green Party, of which he is still a member. Throughout his political career Gil has continued to record and to give concerts, even after Lula appointed him Minister of Culture in 2003. “I have never separated art from politics”, he said in an interview with the French newspaper Le Parisien ten years later. A stance often contested by those who hoped for a more clear-cut position, and to which he finally responded in 2018… in song of course (Ok Ok Ok).

Now, he considers himself an artist above all. Gilberto Gil does not define himself as a militant but rather as a supporter of the Black cause, as he is for the LGBT cause. “Negritude is not just a history of Black people”, he declared on the release of his album Luar in 1981. Along with Palco, a huge success from this album resonating with references to Africa, songs such as Mão da Limpeza (Hand of Cleanliness – Raça Humana, 1984) or Nos Barracos Da Cidade (In the Shack of the City – Dia Dorim Noite Neon, 1985) denounced the living and working conditions of the Brazilian and multi-ethnic population, most of whom still live today in marginalized locations from which most of state services are absent. A social protest that goes well beyond the borders of Brazil, since, in 1985, when his people were celebrating the end of the military regime, the artist wrote Oração pela libertação da África do Sul , a fervent indictment of Apartheid in South Africa.

Brazil’s recent engagement on the African continent owes much to Gilberto Gil. If his presence in the government between 2003 and 2008 helped to bring Brazilian culture back to the front of the international stage, it also served to intensify Brazil’s economic cooperation with Africa and in particular with the Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries. And since his country was the guest of honor, it was understandably Gil who wrote (in French) the official anthem of the Third World Festival of Negro Arts (FESMAN), which finally took place in Dakar at the end of 2010: La Renaissance Africaine, the key song of his current repertoire.

Absent from the protest because of its postponement, Gil symbolically re-interpreted the song with the young South African blacks, whites and mixed-race of the Miagi Youth Orchestra for the documentary by Pierre-Yves Bourgeaud released in 2013, Viramundo, uma viagem musical com Gilberto Gil. Thirty-five years after first having set foot on the African continent, the singer is now returning to meet with the peoples of the southern hemisphere, victims of racism, social exclusion and loss of identity. This global journey, going from the Pelourinho district of Salvador de Bahia to the native territories of the Amazon, the townships of Johannesburg and the arid lands of Australia’s aborigines, is a new occasion for Gil to demonstrate the necessity of cultural diversity in a globalized world.

Gilberto Gil has always preached in favor of a modern cosmopolitanism. “The color black is like a luminous and vibrant carburant, it supplies a sort of telluric energy”, he had already declared in 1982. “It mainly designates intermixing, which is happening more and more all over the world.” This is how he perceived his relationship with Africa and expressed his concept of Negritude, through mixing rhythms and dance, reggae, funk, afro jazz, pop, rock, samba, baião and ijexá. By utilizing the cultural richness of his Afro-Brazilian identity instead of limiting himself to racial grounds.

Gil has helped empower the African continent to rebuild strong ties with its lands and its diaspora. Now 79 years-old, his brand-new single Refloresta (continuing in the vein of titles with Re at the beginning) attests to his new combat, along with the Salgados and TV stars, to reforest the Amazon and to replenish the ecosystems of Brazil’s lands, in order to resurrect the planet.

Listen to the associated playlist on Getup.