On 28 September 1991, a musician who could claim to have ‘revolutionised music five times’, without ever having inspired mockery or ridicule, passed away. Like any good gemini, Miles Davis went where the wind took him, following his seemingly magical intuition. To tell his journey, PAM has teamed up with Get Up, which publishes a series of playlists recounting the trumpeter’s various creative periods. You will find them, one by one, by clicking on the links under the titles of each part of this article, written by John Raby.

Birth of a legend (1945–1955)

Listen to the playlist on Spotify, Deezer or Apple Music.

It all started at the age of eight when Ellington, Hampton and Basie were on the radio. Our young Illinois native was hooked. He soon took up the trumpet, taking lessons and joining his high school band, though never coming first in any competitions. Why not? Because he was Black. In response he worked hard to master his music.

It was at this point that he started to meet people like Clark Terry and Sonny Stitt.Then came the slap in the face that was Parker and Dizzy’s bebop. “I was so shocked that I couldn’t decipher a single note.” Davis left for New York where by day he studied at the prestigious Juilliard School, and by night sought out Parker in the clubs on 52nd Street. When he finally met his hero he mistook him for a tramp. Davis then became enmeshed in the cutting edge of the avant-garde, alongside his new friend (“Billie’s Bounce”). He was nineteen years old. “Bird wanted a different trumpet player from Dizzy. He wanted a more relaxed style, someone who played in the middle register, like me.” Miles took on a more restrained style that he drew from the Saint Louis playbook: a round, clean sound with a slight vibrato.

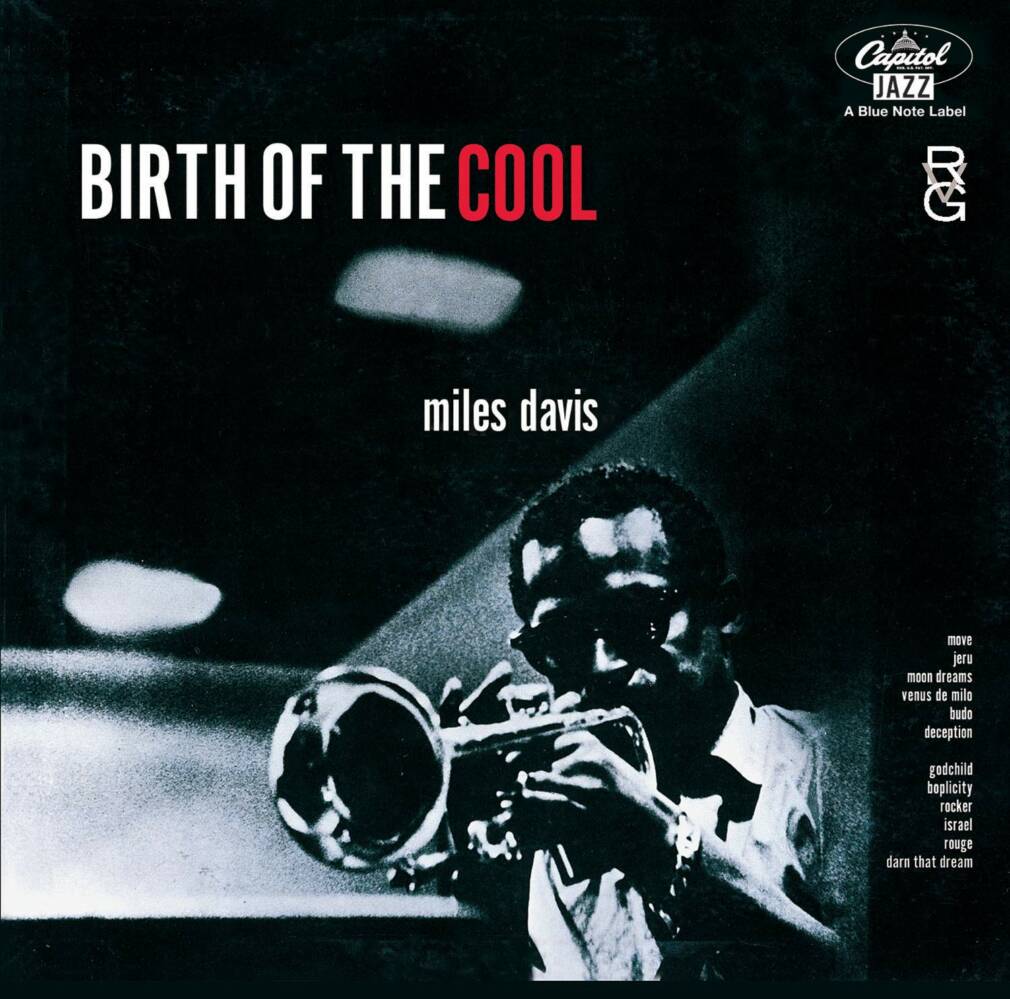

In 1947, he began to make recordings as a band leader (Milestones) and began a lifelong friendship with Gil Evan. “This tall, thin white guy came in with a bag full of radishes that he ate with salt.” Davis remembered of the man who who chiselled out the refined arrangements for “Moon Dreams” on Birth of The Cool. Dizzy didn’t like it, commenting that “you have to sweat your balls off in this kind of music. They softened it up.” Others, such as Chet Baker, jumped into the breach. As for Miles, he worked with Sonny Rollins (“Morpheus”), Lee Konitz (“Odjenar”), Zoot Sims (“Tasty Pudding”), and Charlie Mingus (“Smooch”). Though these are all assured works, a stagnation was beginning to occur. Addicted to heroin, Davis gave up playing and started hustling and pimping in order to satisfy his vice.

At the end of 1953 he locked himself away at his father’s house to get away from it all. He rebirth came with Walkin’: “This album completely changed my life and my career. (…) I wanted to set the music on fire again with improvisations of bebop, that Diz and Bird had started.” These legendary sessions with Monk in 1954 are remembered to this day. On one of Milt Jackson’s songs (“Bag’s Groove”), Miles insisted that the pianist not play during his solo. Angered, Monk danced like a bear around the trumpeter. “When you’re a brass player and you’ve got Monk behind you, it’s like having the devil himself poking you in the ass with his pitchfork – it’ll either distract you or give you wings to fly,” remarked Laurent de Wilde in an apt analyses. Drama also occurred on “The Man I Love”. During his solo, Monk remained silent for ten interminable seconds. It was too much. Miles gave him his marching orders and asked his pianist Red Garland to imitate the airy style of Ahmad Jamal (“Will You Still Be Mine”). His intuitions were astute and the first quintet was to become legendary…

Miles ahead (1955–1960)

Listen to the playlist on Spotify, Deezer or Apple Music.

After Charlie Parker’s death, Miles decided to form his own quintet. Brando, Sinatra, Eva Gardner – everyone came to hear them. “So there was Coltrane on saxophone, Philly Joe on drums, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and me on trumpet. And faster than I could have ever imagined, the music we were making together became incredible. It was so good that it gave me and the audience chills. Shit, it got scary real fast, so much so that I was pinching myself to make sure I was really there.”

The trumpeter recorded the albums Cookin’, Relaxin’ and Workin’ in quick succession in order to end his contract with Prestige. In 1956, the band recorded the Monk classic, “‘Round Midnight”. Every night after playing it Davis asked Monk, “How was it tonight?” To which the pianist replied, looking very serious, “not good“. They kept this up for some time. “’That’s not how it’s played‘, he would sometimes say to me with a mean, exasperated look on his face. Then one night he said, ‘Yeah, that’s how you play it.’ That made me crazy with happiness. I had found the sound.”

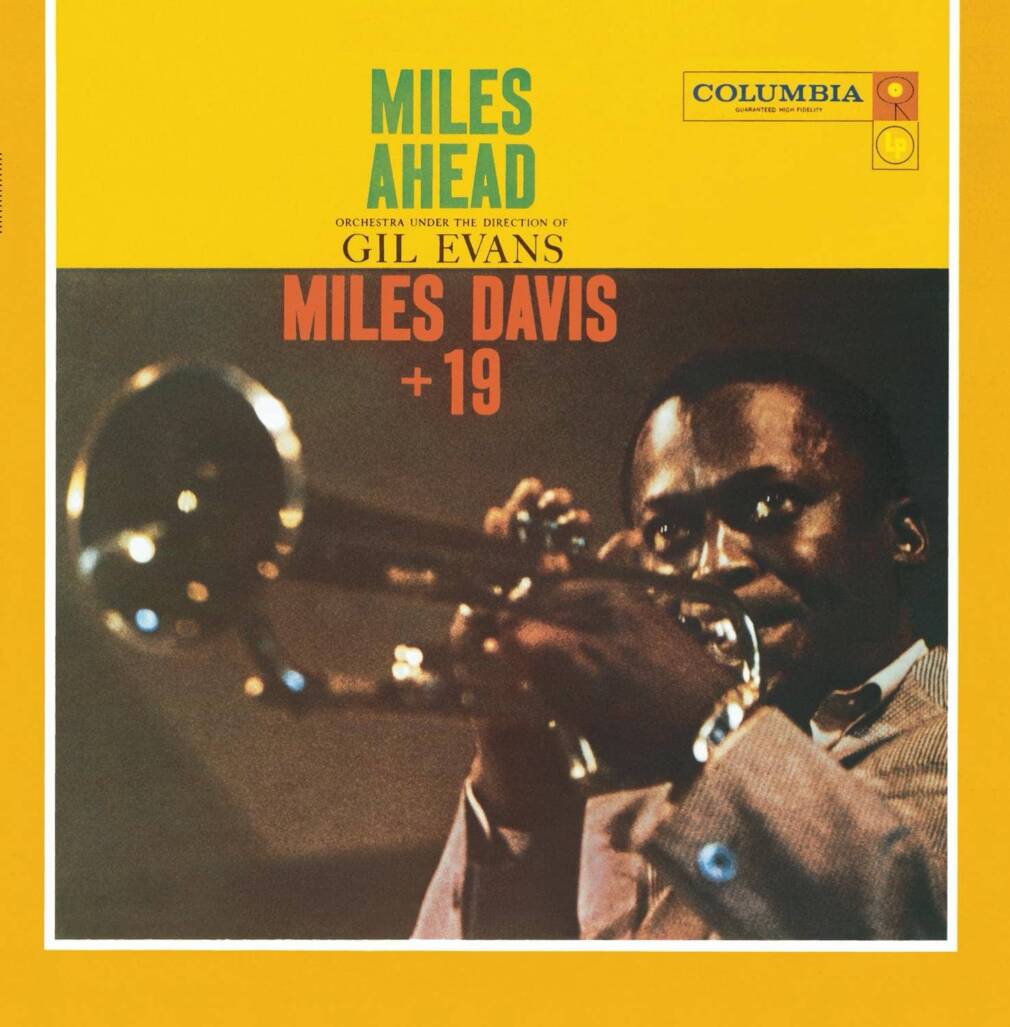

Coltrane dove into dope and Davis beat him up. So Coltrane went to work with Monk and pretty soon Davis had dismisses his quintet in order to work with a larger ensemble under the aegis of Gil Evans, and Dizzy admitted to having worn out his first Miles Ahead album in just three weeks… Miles went to play at the Saint Germain club in Paris, the same place where he had fallen madly in love with Juliette Gréco. One night he improvised the music for Ascenseur Pour l’Échafaud, a film by Louis Malle. When he returned to New York, saxophonist Cannonball Adderley joined the reformed quintet that recorded Milestone. “Trane and Cannon were really playing like crazy and had now gotten used to each other. It was my first record written in a modal form.” Red Garland and Philly Joe Jones left and were replaced by Jimmy Cobb and pianist Bill Evans, a connoisseur of Ravel and disciple of Lennie Tristano. Coltrane, who had meanwhile given up heroin, set off on his more esoteric phase. In the late 1950s, things started to really hot up.

Davis collaborated again with Gil Evans on a version of Porgy & Bess. “When Gil wrote the arrangements for “I Love You, Porgy”, he only wrote me some scales, no chords… It gave me a lot more freedom and space to hear things… There are fewer chords and infinite possibilities for what you could do.” Then there was Kind of Blue which followed a similar methodology. As Bill Evans would recall, Davis had only brought sketches of scales and melody lines to improvise on. Once the musicians were together, he simply gave brief instructions and the symbiosis worked like magic. 1959, the year of the album’s release, was a landmark moment.

The following year, the trumpeter worked with Gil Evans on the adagio movement of “Concierto de Aranjuez”, a piece for guitar by the Spanish composer Joaquín Rodrigo. It’s a masterpiece, even if the composer hated Davis’ interpretation. “That’s interesting. Let’s wait a bit until he gets his royalties. Maybe then he’ll start to like it…” The dissolution of his quintet left Miles orphaned, though wouldn’t be long before he found other musicians with whom to innovate again and again. He had no choice – it was that or die.

Seven years to Heaven (1961–1968)

Listen to the playlist on Spotify, Deezer or Apple Music.

Coltrane played one last time for his friend (“Teo”) before leaving for other horizons. Free jazz was in full swing with the first records by Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. But Miles wasn’t a fan. He called the pianist “a sad piece of shit” and mocked cornet player Don Cherry “with his little instrument“. And what was Miles up to?

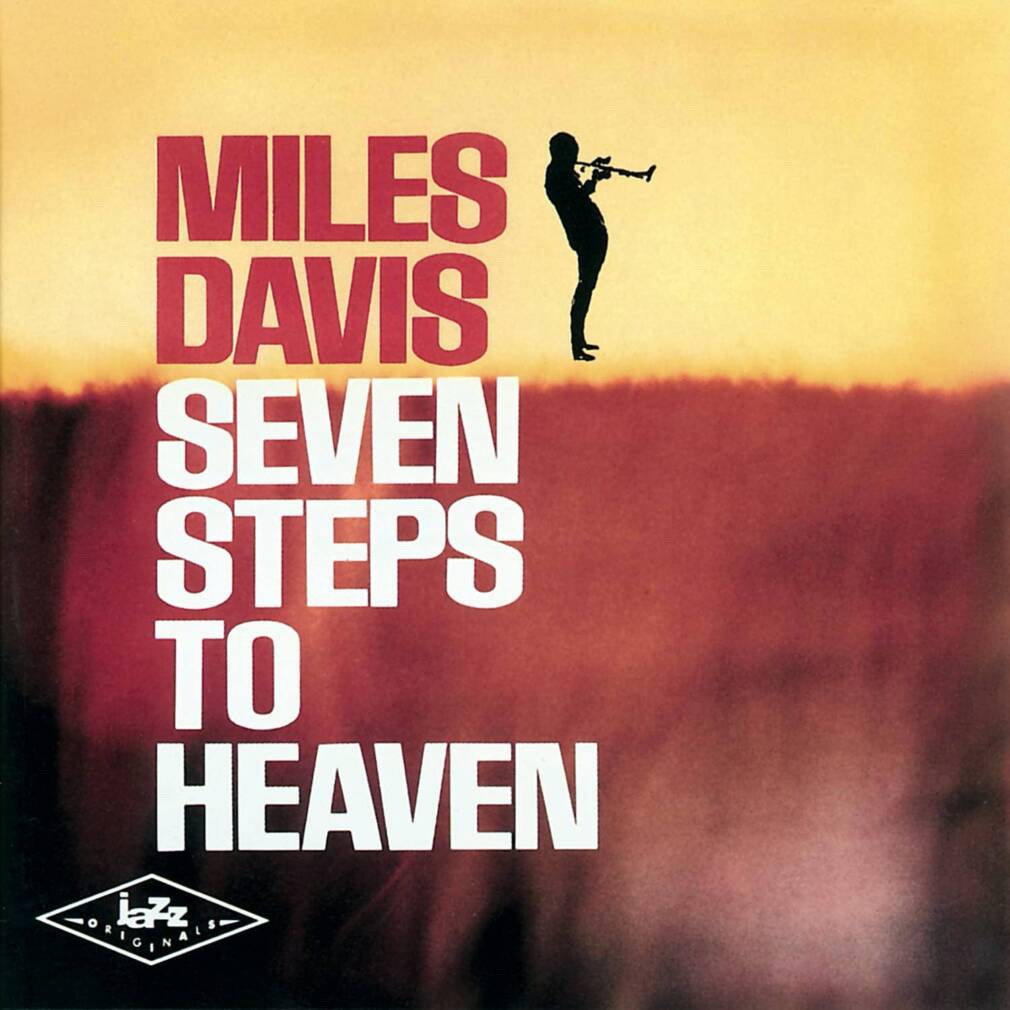

Left to his own devices, went off to find himself. To do so he’d need some new musicians. He fell in love with seventeen-year-old drummer Tony Williams. “I thought I’d cracked when I heard what that little bastard was doing. All my excitement came back and I decided I had to have him.” Davis also hired the young pianist Herbie Hancock – who had already had success with “Watermelon Man” – and Ron Carter to play double bass. With his rhythm section in place, Davis went on tour, taking George Coleman on saxophone (“Seven Steps to Heaven”). His playing, too faithful to the old Coltrane, frustrated the younger musicians. A fan of free music, Tony Williams convinced Davis to hire Sam Rivers for a few dates in Japan (“So What”). But it was Wayne Shorter that the trumpeter wanted, though he had to wait until his involvement with the Jazz Messengers was over.

The saxophonist finally joined the group in 1964. From then on, a new creative episode began with what would become known as ‘Miles’ second quintet’. Miles felt he had all the elements he needed to push his own limits. “Tony was the fire, the creative spark, Wayne the designer, Ron and Herbie the anchors.” Together, through a series of revolutionary albums (E.S.P., Miles Smiles, Sorcerer) they developed an aesthetic of ‘Controlled Freedom’, a style of controlled improvisation that sought to avoid some of the pitfalls of the total freedom advocated by free jazz. Instead of sticking to a succession of modes as in the case of Kind of Blue, this new quintet increased the tonal possibilities by multiplying the modes, thus creating new harmonic foundations and other progressions. In fact, the music was arguably more open, ambiguous and unstable, but it never lost its way.

From 1965’s E.S.P. onwards, everything became based on a kind of musical telepathy. The orchestra was no longer organised around a single soloist. All the musicians improvised together, while remaining attentive to each other in order to preserve harmony and coherence. Building on this fruitful basis, a new stage was soon reached with the integration of electricity. From 1968 Davis encouraged Hancock to play a Fender Rhodes. “The acoustic piano is an outdated instrument. It belongs to Beethoven and no longer fits with our times.” In the same vein, Davis sought to incorporate an electric guitar. This new craze came from his lover at the time, Betty Marbry. A young soul singer with a strong temperament, she made him listen to James Brown and meet Jimi Hendrix. She also chose psychedelic clothes for him (glasses with oversized lenses, lizard skin trousers, leather bracelets…).

Who would have imagined that soon Miles Davis would open the show for Neil Young & The Crazy Horse? Or set the Isle of Wight on fire with the legendary “Call It Anything”? In reality, what was coming was the final incarnation. Electricity, drugs, and a shooting…

Funky monk, dark satin (1969–1970)

Listen to the playlist on Spotify, Deezer or Apple Music.

With the explosion of pop and soul music, jazz was losing ground and Davis no longer had as much power to negotiate fees with his record company. He couldn’t stand the fact that long-haired white guys were playing the blues and being praised for it. He felt the tide turning and started looking for a new sound: “Through listening to James Brown I was moving towards the guitar.”

It was time for a revolution, the type that would see our man of cool sounds move towards electricity, powerful rhythmic beats, psychedelic covers and eccentric clothing. Had he sold his soul in order to maintain his lifestyle and feed his ego? Miles was no copy cat. Rather than making any sudden changes he let his sound mature with subtle and thoughtful integrations, in step with his magical intuition. With In A Silent Way (1969), he got rid of jazz’s chord framework in favour of pastoral music reduced to a few simple melodies, repeated in different ways. In this feverish jungle atmosphere, belonging neither to jazz nor to rock, he was laying the foundations of what would go on to be called ambient music.

The recordings became collective improvisation sessions, conducted by Davis and then recomposed in post-production by Teo Macero. During this period our sound wizard expanded his orchestras and brought together a large number of important musicians: John McLaughlin, a young English blues guitarist, Dave Holland on bass, Joe Zawinul on organ, and Chick Corea on electric piano. Tired of not being able to improvise like a madman, Tony Williams left after In A Silent Way, and was replaced by Jack DeJohnette. The double album Bitches Brew was recorded in three days in August 1969. According to Teo Macero the atmosphere of the album was the result of a fight: “In my opinion, Bitches Brew owes its power to a violent argument I had with Miles about my secretary. He wanted me to fire her but I had no intention of doing so […] And the more it went on, the more we were yelling – we almost beat each other up in the studio.” A jazz-rock masterpiece, Bitches Brew sold half a million copies. This was followed by a series of mystical gems with sitar and tabla (“Recollections”).

Davis gradually changed course, solidifying his music, going deeper and deeper into the famous groove that obsessed him. For him, only funk could be authentically Black, with blues being vampirised by white people. Hooked by Hendrix’s Band of Gypsys, he recorded “Right Off” in April 1970. It all started with a boogie improvised by John McLaughin on guitar, Michael Henderson (Stevie Wonder’s former bassist) and Billy Cobham on drums. Simply by entering the studio Miles was jumping on that bandwagon. Red light.

Herbie Hancock stopped in and was given the worst keyboard in the world: a farfisa. Davis played with Keith Jarrett and Hermeto Pascoal on the ethereal “Little Church” recorded in June 1970. But after the miracle of Bitches Brew, Miles was to suffer nothing but commercial failure. The public didn’t get it, and Miles was in a bad way. Dressed as a pimp, he was consuming disturbing amounts of cocaine and alcohol. The next few years were to be an unparalleled artistic ascension, but also a veritable descent into hell. Miles was losing it.

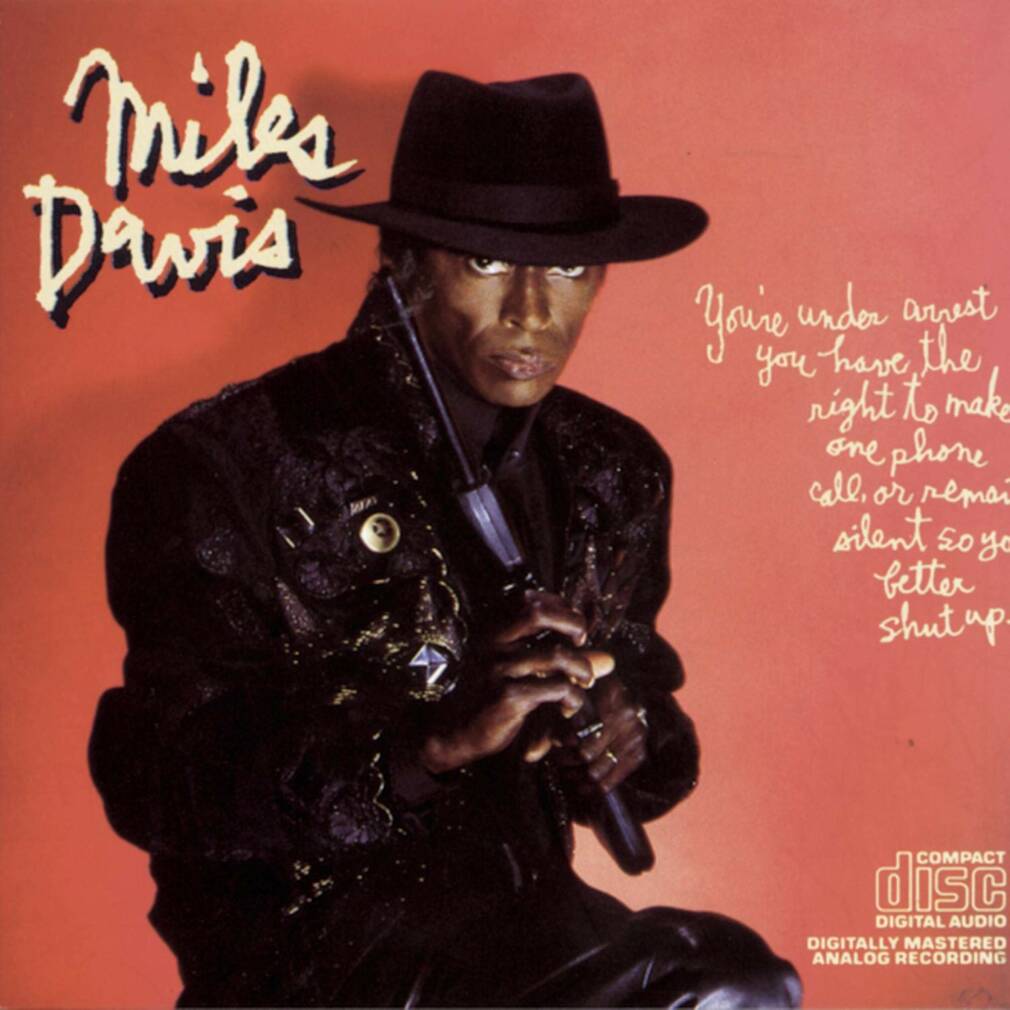

He is finally under arrest Miles Davis (1971–1993)

Listen to the playlist on Spotify, Deezer or Apple Music.

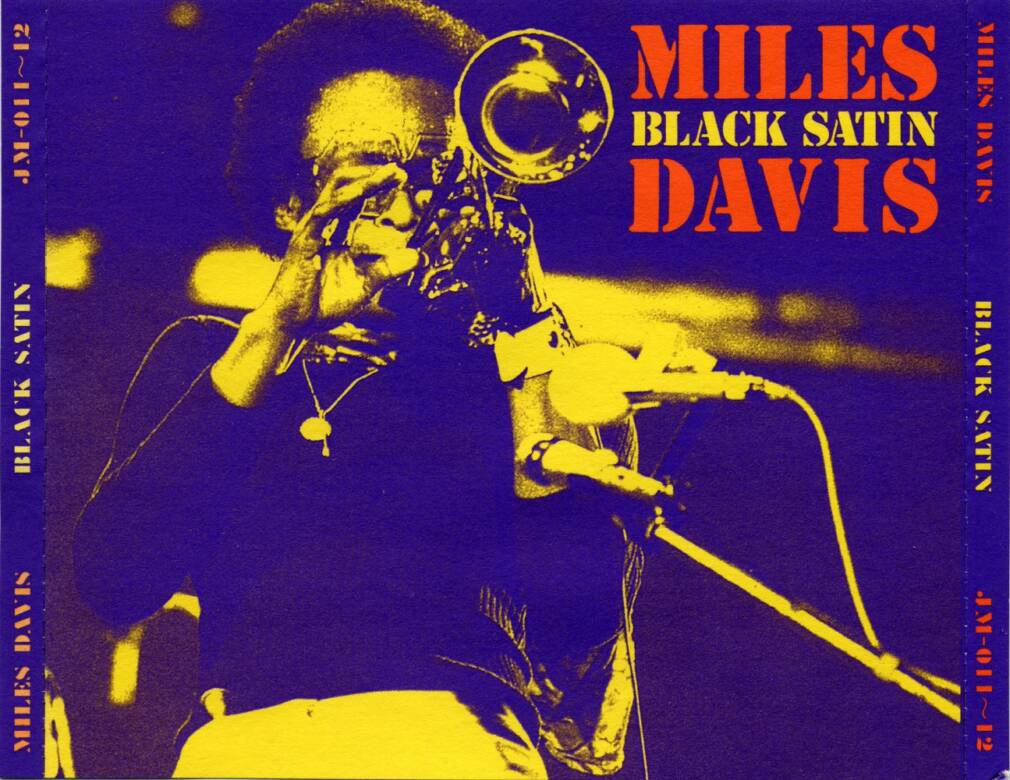

In 1972, Miles Davis returned to the studio with Sly Stone, James Brown and Stockhausen in the lead and he recorded On the Corner (“Black Satin”). No more solos here. Everyone was concentrating on the ensemble, and in doing so created a sound like floating, raging magma. As saxophonist Dave Liebman recalls: “[Davis] plays a note, and everybody gathers on that note; or he plays something and lets the band go on. He says, ‘don’t go through with your idea, let the others finish it’ […] He creates an overall climate where each solo is just a small fragment of the bigger picture.”

Inspired by Hendrix, with whom he did not record, Davis plugged a wah-wah into his trumpet. This meant he had to change his whole playing style and play even fewer notes (“Ife”). It was no longer a question of phrases but of glissando notes, inarticulate ornaments, and a sort of incantation between cries and tears. Sometimes he would put down his trumpet to smash out some nightmarish funk notes on the keys (“Rated X”). The risk-taking was dizzying and he paid for it dearly: pneumonia, kidney stones, ulcers, tumours, a bad hip… He even came close to a heart attack. One time he crashed his Lamborghini and broke both his ankles. In June 1974 he played the lilting tune “He Loved Him Madly”, a funeral meditation that the trumpeter addressed to the deceased Duke, but perhaps also to himself…

After an insane tour immortalised by the albums Agharta and Pangaea, Miles broke down. “I had nothing left to say artistically and was spending all my time in hospitals. I started to see pity in the eyes of people who looked at me, like when I was a junkie. I preferred to give up the thing I loved most in the world, music.” As Gil Evans recalled, “Miles’ sound comes to him very hard: it takes a lot of energy, jaw strength, and muscle to recreate his own sound all the time.” For five years Davis locked himself away in his home, hooking up with sex workers and getting addicted to speedball (a mix of coke and heroin). It wasn’t until the 1980s that he re-emerged, encouraged by new followers of the ‘Controlled Freedom’ movement.

In order to warm himself up again he went on tour. The concerts were a huge success. After an episode with John Scofield, Miles played for Toto, flirted with Prince and played over some of Robert Irving’s electro arrangements. Bassist Marcus Miller also played. In essence, Miles followed the same path as during his electric period, but this time in a calmer, more inoffensive vein. While the dancey funk of Tutu got people moving at the time, today it seems rather cliched. As Frank Bergerot, one of Davis’ most reliable biographers, wrote: “He – who constantly played on the edge of the abyss – seemed to us to have given in to the rhythmic certainties of a music that was too well defined and succumbed to an “all-synth approach” without really solving the problem he himself raised several times: synthesizers sound ‘white’“.

It is true that the charm of his tone was occasionally able to blossom when the stylistic mawkishness of the eighties was kept in the background (“Time After Time”). Miles Davis’ sound has never gone away, even in death. The rapper Easy Mo Bee completed some unfinished tapes (“Doo-Bop”) after the trumpeter’s death on 28th September 1991. And forty years later, others are still digging up recordings from the back of drawers that continue to add to the greatness of the man who left an unprecedented mark on music in the 20th century.