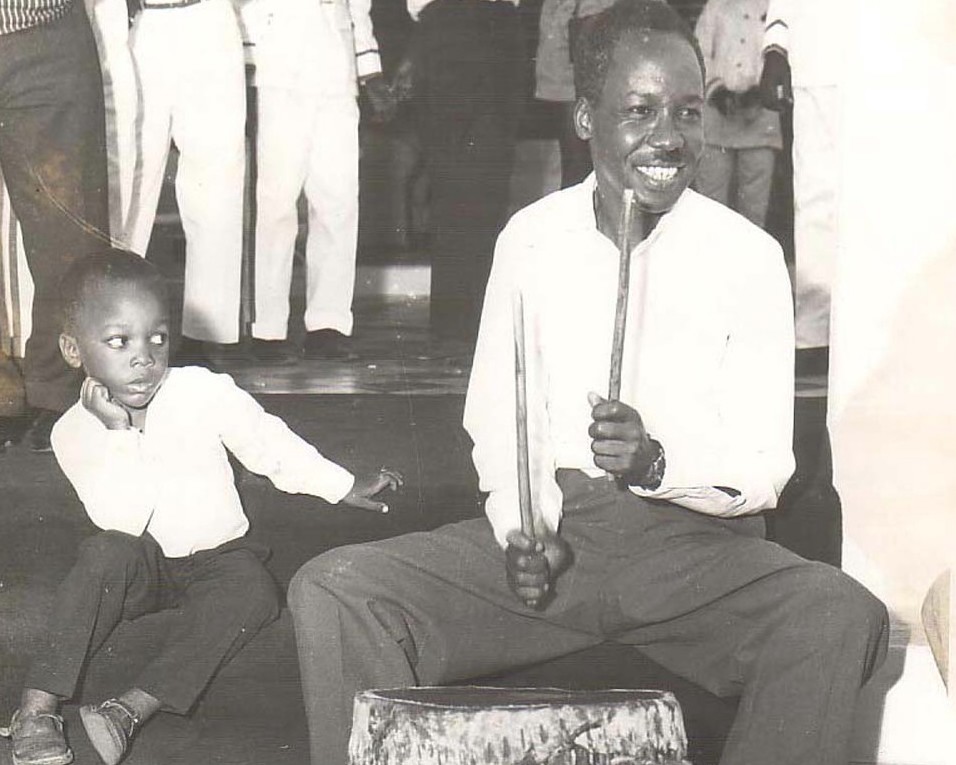

Known affectionately as “Mwalimu” meaning teacher – Tanzania’s first president Julius Nyerere the centenary of whose birth is celebrated this year belongs in the pantheon of pan-Africanists. An anti-colonial activist, organiser and statesman, Nyerere was also a scholar and poet publishing the first Kiswahili translations of William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Macbeth and The Merchant of Venice. Taking possession of the literary canon of the coloniser was his first creative flex, but Nyerere’s other cultural contribution upon becoming president would be the state sponsorship of dance bands who would soundtrack the epoch with a new music known as “muziki wa dansi”.

A musical nephew of soukous, muziki wa dansi or simply “dansi” or “swahili jazz” (employing that catch-all suffix used by big bands of the era everywhere from Guinea to Ethiopia) was a social dancing music originated by large bands organised as cooperatives in keeping with the political values of Nyerere.

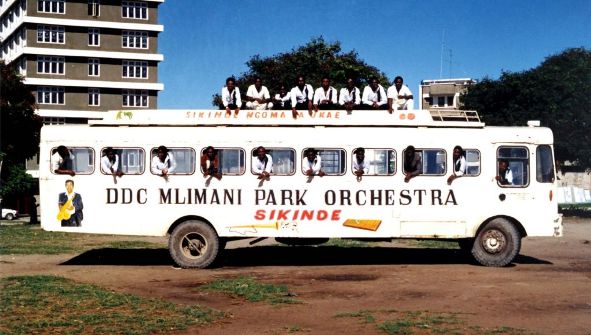

Giants of the genre like Orchestra Safari Sound, Mlimani Park Orchestra and Maquis International enjoyed great longevity, and remain in the case of Maquis International a huge source of pride for Tanzania, existing in no small part thanks to Julius Nyerere.

Born the 13th April 1922 in the Northern town of Butiama in what was then Tanganyika, Julius Kambarage Nyerere was the son of a regional chief meaning that although he came of age under colonial rule, from an early age he had a strong sense of what African administered leadership looked like and a strong sense of village communalism. A brilliant student, after completing secondary education Nyerere trained as a teacher at Makerere University in Uganda before obtaining a masters degree at Edinburgh. Returning to Tanganyika he worked as a schoolteacher before becoming increasingly involved in politics, and in 1953 he became president of The Tanganyika African Association, transforming it into the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) the following year.

A decade of activism, organising and political growth followed during which Nyerere overcame the inertia and subterfuge of a colonial government reluctant to accept the inevitable to become president of Tanganyika on the 9th December 1961 (later renamed as Tanzania in 1964 upon unification with the island of Zanzibar.)

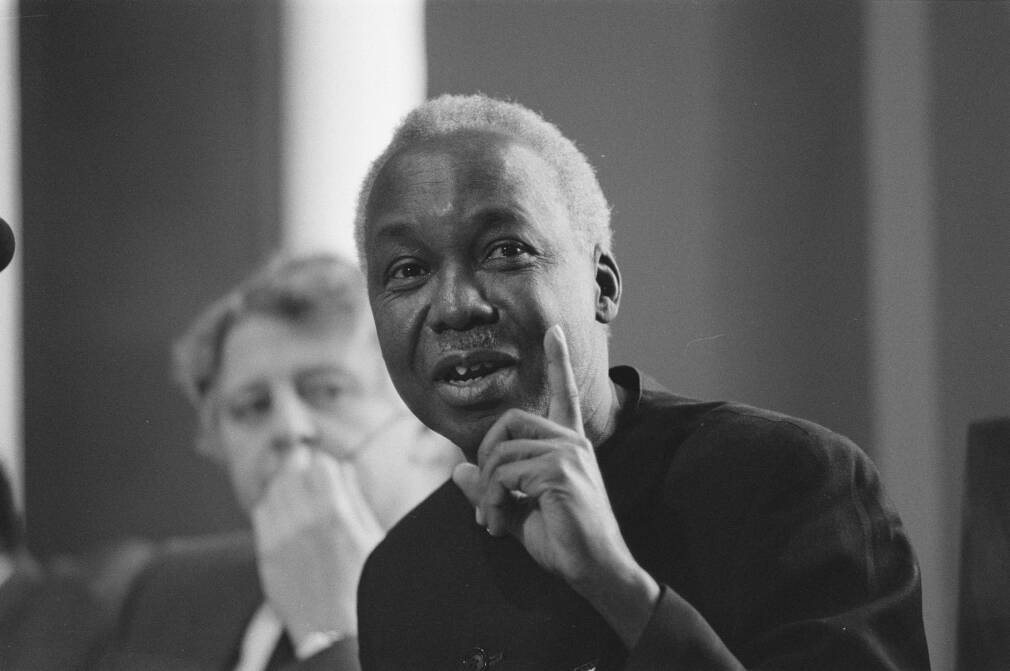

It was not long into his premiership that Nyerere published the article “Ujamaa” (familyhood) his definitive treatise on collectivism in which the pedagogue turned president put down on paper many of the ideas that would inform his two decade presidency of Tanzania.

As a teacher Mwalimu emphasised education which he insisted must be in Kiswahili so Tanzanians might free themselves of colonial language and learn to think independently. Emphasizing self-reliance and cooperative economics, Nyerere also called for the villagisation of production but under a Tanzanian rather than a tribal sense of identity.

Recognising the potential of music to create pride in the new republic of Tanzania (and as a vehicle for valorising Kiswahili language) Nyerere decided to introduce a sponsorship system whereby bands could be financially supported by government departments and institutions. And so institutions like the Nuta Jazz Band named after its sponsor The National Union of Tanzania would be born. Borrowing from Congolese rhumba which had been a fixture of nightlife in Dar Es Salam since the 1950s, bands like Nuta Jazz Band employed the same close harmony and guitar centred approach but sung their lyrics in Kiswahili rather than Lingala answered by lilting brass before jamming out on the the familiar extended outro or “Sebene”.

Typically large bands numbering from a dozen up to 25 members, dansi groups were encouraged to organise themselves as cooperatives with musicians receiving a regular wage or salary which allowed many to save enough money to go on to start their own bands and resulted in the multiplying of muziki wa dansi.

An ownable sense of style known as “mitindo” came to define this new swahili jazz for which signature dances were created, and in this way dansi bands who typically worked hard playing residencies of seven nights a week competed fiercely for followers and became brands as much as they were bands. Members came and went, but groups like DDC Mlimani Park Orchestra which began as the resident band of the Tanzania Transport & Taxi Services owned by the Mlimani Park Bar in Dar es Salaam (and later by the Dar Es Salaam city council) changed hands like football teams beloved of their supporters. These rivalries thus helped diversify the Musiki Wa Dansi scene.

Another notable group of the period were Orchestra Maquis Original. Working out of their headquarters at the Lang’ata Social Hall, Orchestra Maquis Orginal would develop a signature mitindo accompanied by a dance known as “Kamanyola bila jasho” (to dance Kamanyola without sweating). Positioning themselves as a poised and sophisticated dansi band, Maquis Original (true to their cooperative credentials) also owned a farm.

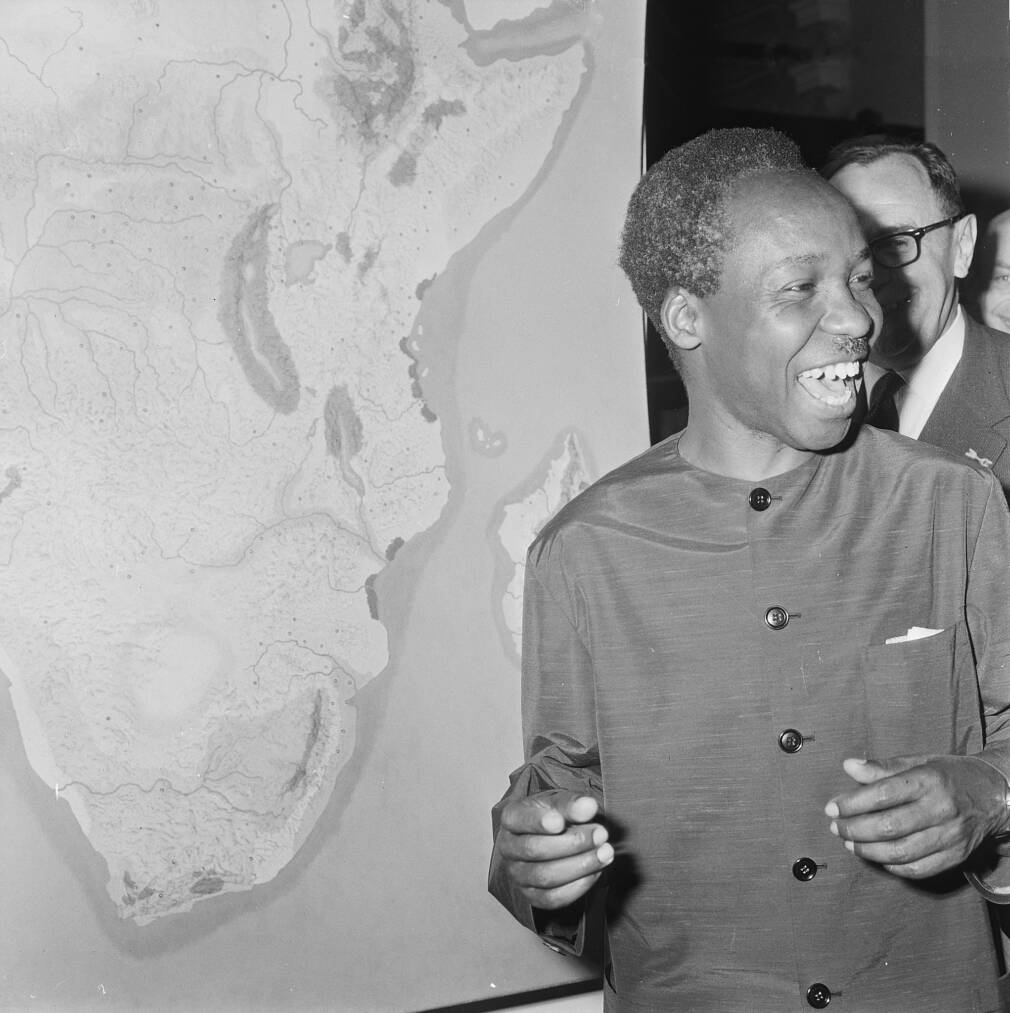

And so as dansi bands came to score the era, Julius Nyerere transformed Tanzania into a modern African state and created the blueprint for African socialism through the prism of pan-Africanism.

He would be present at the founding session of The Organisation of African Unity, and Mwalimu was a peer and friend of Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya) Milton Obote (Uganda) Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Haile Selassie (Ethiopia) and Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt) always cutting a sharp figure and immediately recognisable in his trademark Nehru jacket or kofia cap.

Nyerere of course had (and has) his critics. One party politics was a key component of Ujamaa and he approached most areas of politics and society with absolutism.

Nonetheless, without this teacher turned president who led Tanzania from 1961 to 1985 (and is perhaps less celebrated than Nkrumah or Lumumba..) pan-Africanism and muziki wa dansi would be the poorer. Happy birthday and asante sana (thank you) Mwalimu!