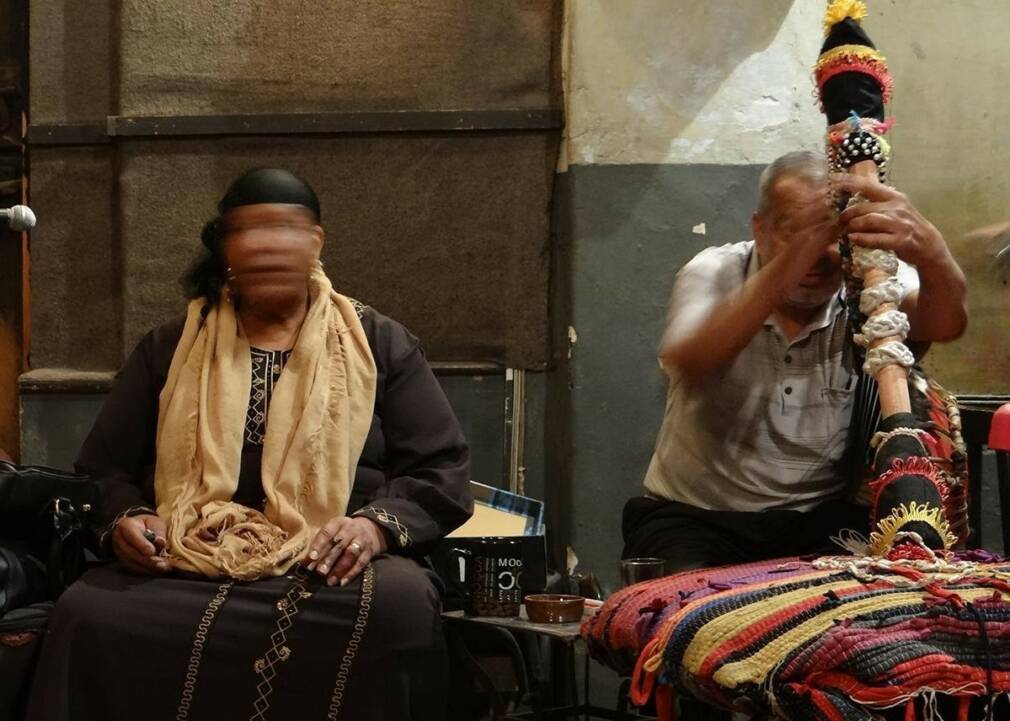

In the heart of a Dutch winter the Jacobikerk, a small Protestant church in Utrecht and the traditional starting point for Dutch pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela, awaits a sacred event. This is the fifteenth edition of Le Guess Who? festival, one of Europe’s most audacious musical events, and tonight the festival is hosting a mysterious female-led Egyptian ensemble called Mazaher. Their arrival is exceptional – the group has not performed in Europe for more than fifteen years – and so is their music. The six members of Mazaher are the last practitioners of zãr, a therapeutic trance ritual that heals and delivers. But for whom and from what exactly?

In the Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology (Facts on File, Inc. – 2009) Rosemary Ellen Guiley refers to zãr as evil spirits who torment a human host, usually a woman. “The victim is then brought before a Shechah (or Chikha, ‘elder’ in Arabic), the clairvoyant-therapist who conducts the ceremony and will identify precisely which zãr is responsible for the disturbance from among a vast pantheon of spirits. Once questioned – sometimes in the zãr language, understandable only to the Shechah – the evil emissary asks to receive a certain number of gifts in order to be satisfied, before it will stop tormenting its host.”

The zãr then designates a group of spirits and, by extension, which ritual will be required in order to appease them for the salvation of the possessed. With an average age of over sixty-five, the members of the Mazaher Ensemble are the last heirs and practitioners of this ceremony in Egypt. The 90 minute concert they gave that night, in the heart of this astonishing Protestant church, is only a tiny taste of all that can unfold during a ceremony: satisfying a spirit can require up to seven leilas (‘nights’ in Arabic) of ecstatic song and dance, offerings, fiery percussion, incense, and lamb’s blood rubbed onto the victim’s forehead.

“What we do has nothing to do with exorcism”, says Madiha, the lead singer of Mazaher. ‘The objective of zãr is for the participants to find harmony with their inner selves. Our music, our songs are primarily spiritual, and they help relieve the listeners of stress and bad vibrations.” The doyenne of zãr has been singing since she was 11 years old. Her mother was also a zãr singer, who in turn started singing with her own mother as a young child in Upper Egypt.

“Sufi folk beliefs and anti-Islamic African rites”

The zãr practised by Madiha and the members of Mazaher has its roots in sub-Saharan Africa, with the Kanuri, Songhay, and Hausa peoples, amongst others. This rite was born in the melting pot of a variety of different African traditions, mixed with local Islamic beliefs, and then transported by spice traders, Arab merchants, and musicians. Some sources speak of a Bilalian cult, in reference to Bilal, the freed slave and companion of the Prophet of Islam. Like its distant cousins Brazilian Candomblé, Haitian voodoo, and Cuban Santeria, zãr is a blend of cultures, born of slavery.

Whether through oral traditions, dance, or music, the history of the rite is difficult to date. Its geography, however, is better known. Over the centuries the ritual spread throughout the Sahara and is now practised from West Africa, in Morocco and Mauritania, to Sudan. By crossing the Persian Gulf via the Hormuz delta (zãr enclaves can be found on the island of Hormuz) the rituals spread as far as Iran. The ritual is essentially the same everywhere: ritual trance rhythms intended for therapeutic and meditative benefits.

“We are dealing with religious syncretism, merging local popular Sufi beliefs with African, pre-Islamic rites”, explains Zouheir Gouja, a Tunisian musician and specialist in African-Maghrebian ritual trance traditions. “It is called gnaoua in Morocco, diwân in Algeria, stambali or benga in Tunisia, and zãr in Sudan, Egypt, northern Ethiopia, and Iran. Each collective has its own musical repertoire and songs, which structure the ritual and direct its development.”

You are probably familiar with the sounds of the Gnaoua community and now that of the stambali, played mainly with iron castanets (called karkabous or chkacheks) and a stringed lute (the guembri). The zãr played by Mazaher brings together a set of instruments that would make any ethnomusicologist giddy with pleasure. In addition to the predominance of singing and the rhythms of the doff (a large rounded drum) Egyptian zãr is distinguished from other forms of trance-inducing music by the use of the tamboura – a six-stringed lyre, often encrusted with cowrie shells – and the mangour – a leather belt around which dozens of goat hooves are hung. When dancing, the mangour player produces a distinct watery trickling sound.

An uplifting ritual in danger of extinction

Ahmed El Maghraby, a language professor at the University of Ain Shams in Cairo, created the group Mazaher in 1999. It is a truly national, all-star band that brings together the last female practitioners of the genre in Egypt. Three years later, the artistic director founded the Egyptian Centre for Arts and Culture, aka Makan. There, zãr lives on, with one concert a week, every Wednesday evening. zãr, like much of African ritual trance music, suffers from a lack of institutional recognition on the one hand, and a lack of interest on the part of its various audiences on the other. “zãr was once exploited by the Egyptian film industry”, says Ahmed. “The image of the ritual was then turned into something folkloric in films where directors pushed its mystical dimension. The cultural and social aspects were completely ignored. Today, Egyptian elites despise zãr for its chaâbi side, which means ‘popular’ or ‘folk’ in Arabic. It is as if this practice was not socially worthy of representing Egyptian culture,” El Maghraby laments. For the founder of the Makan cultural centre, “the general public has largely turned away from its ancient, local roots, in favour of the mainstream. The people want the mainstream. For a long time the Egyptian public have wanted pop or rap, in order to imitate the West. Now what’s worse is that today’s youth are looking to the glitz of the Gulf and the riches of Dubai.”

It hasn’t always been like this. “From the 1930s until the early 1980s, zãr was practised in many homes in Cairo”, explains Egyptian singer and producer Nadah El Shazly. “My grandfather told me that as a child, behind the half-closed doors of his house, he saw how his aunt danced frantically with other women, and how he was hypnotised by the percussion and their singing.”

By the end of the twentieth century however, the ritual had slowly regressed until it was seen as something mysterious and secretive. “The reformist and nationalist voices that were stirring up Egypt at the time deemed it backward and barbaric, while conservative Wahhabis condemned it as blasphemous,’ continues Nadah. “The misinformation around zãr continued to spread and by the 1990s the practice was heavily stigmatised.”

Today, the future of the ritual is uncertain. There are said to be only about twelve zãr practitioners left in Egypt and most of them form Mazaher’s line-up. Due to the difficulties to make a living as a practitioner, the descendants of zãr leaders have not taken up the mantle. Even the children of Madiha, the leader of Mazaher, have not taken over from their mother. “We are now in a race against time,” says Ahmed, artistic director of the Mazaher Ensemble. They all fear that with the passing of the last members of the group that the ritual, in its Egyptian iteration at least, will die out.

“Apart from rare, private home practices, and a handful of special traditional events outside Cairo, Makan is the last place where zãr performances can be seen in Egypt”, explains the musician Nadah. “The covid pandemic and the curfews almost dealt us our final blow”, adds Ahmed. “What we offer at Makan is first and foremost a space for expression. It’s a framework in which Mazaher can continue to spread its music. But it is not a complete ritual,” the founder warns. “I remember the band’s first concert at the Centre. They arrived at 5 o’clock and didn’t leave until the same time the following day!” With pieces that can easily last an hour and a half, Makan is forced to ‘truncate’ the performances to make them accessible to a public of non-initiates. “These are concerts that integrate, as faithfully as possible, the essential musical elements of the ceremony without breaking the ritual. The audience can listen to the music, but also feel how the ensemble works towards a form of reconciliation between the human spirit and the other spirits that surround it.”

At Makan there is no platform or backstage. “The musicians and the audience are all mixed together, united in an intimacy necessary for the ritual. When our little venue opened, seventy percent of the audience was foreign, made up of Europeans and expatriates,” says Ahmed, Makan’s founder. “Sometimes these expats and tourists would invite an Egyptian friend to a zãr party, and that’s how we managed to capture the local public, and help them to rediscover their own heritage.” Today, Mazaher is looking north for recognition. “Being featured on big musical exchange platforms like Le Guess Who? makes us more visible in our own country. I admit it’s a strange path, even a bit crazy, but it’s by walking this Northern road that Mazaher and zãr will once again find the light.”

Possession and safe spaces: women at the heart of African ritual trance rites

A notable idiosyncrasy common to Egyptian zãr, the Stambali ceremonies from Tunis, and the Banga of the Saharan fringes, is the important place accorded to women within these rituals. They are priestesses, patients, clients, dancers, and musicians, and are at the heart of these ‘cults of possession’. “Whether they order them or benefit from them, women are in fact over-represented in African ritual trance rites,” comments Ahmed El Maghraby. “In the end, I have the feeling that women participate in these ceremonies without really thinking about fellowship, or renown. The clients, the patients, the regulars of the zãr go to these ceremonies first and foremost because it makes them feel good.”

Women go to these ceremonies in order to take time for themselves. Largely absent from North African public spaces that are so often oppressively governed by men, women can find in the ecstasy of ritual trance ceremonies both a symbolic and a real means of escaping patriarchal social domination. It gives them free access to the sacred.

Are the zaouias (fellowship sanctuaries) the first safe spaces for women in the Arab-Muslim world? This hypothesis is shared by many observers of these rituals and it is the opinion of author and professor at the University of Tunis, Hédia Ouertani-Khadhar. “Between public and private spaces, the situation for women changes. They cover themselves in the street but can attend trance rituals with men in private.”*

French philosopher and sociologist Georges Lapassade**, an observer of Moroccan Gnawa, refers to such rituals as a ‘religion of women’. In Tunisia, Stambali rituals raise even more direct questions about gender: the ritual leader – the arifa – might be a man, but will take on all the mannerisms of an old woman. With an ultra-binary public life, Islamic north Africa seems to grant a certain tolerance – and it is perhaps the only example of this – towards the gender fluidity that is expressed within a community of followers.

Stambali, banga, gnawa, diwân, Egyptian zãr. Possession rites in Africa don’t only deliver spirits from oppression: they tolerate sexual and social ambivalence, and liberate their practitioners.

But for how much longer?

Ajabu Records of Sweden is responsible for the distribution of Mazaher’s music. You can find more information about the label here.

You can listen to zãr every Wednesday in the belly of Makan. Their Cairo address is 1 Saad Zaghloul St. El Dawaween. Further information about Makan can be found here.

* c.f. Femmes et rites de possession en Afrique sub-saharienne, en Tunisie et au Brésil (Women and possession rites in sub-Saharan Africa, Tunisia, and Brazil) by Hédia Ouertani-Khadhar. © Perpignan University Press, 2011

** Lapassade Georges, Les gnaoua, un vaudou maghrébin (Gnawa, a north African voodoo) Revue Zellige n° 3, Service Culturel, Scientifique et de Coopération de l’Ambassade de France au Maroc, October 1996.