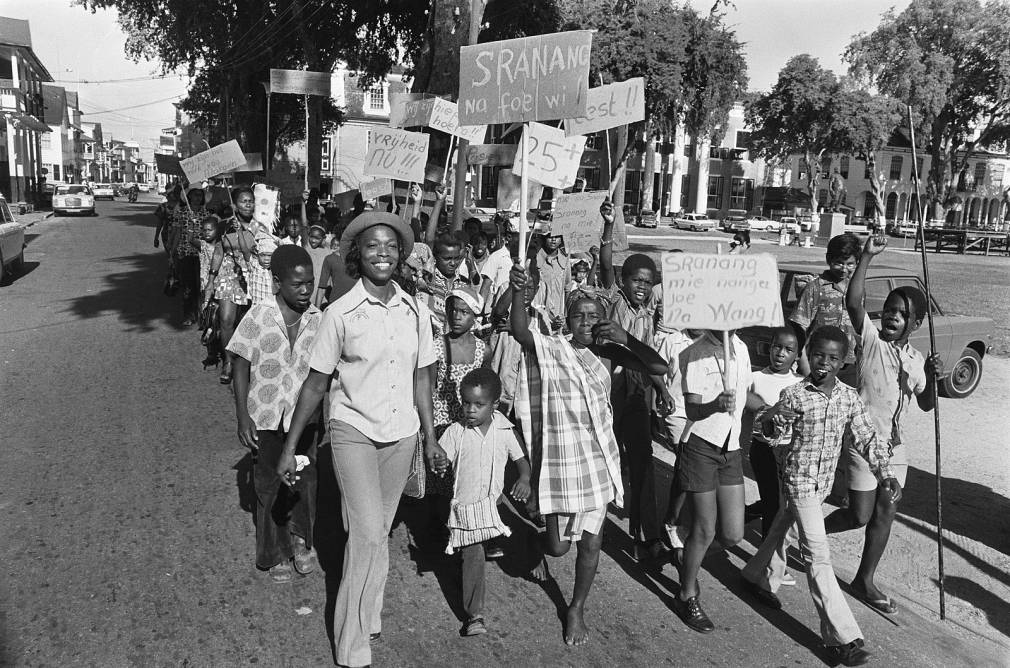

As the Surinamese people oust President Bouterse after a decade-long rule, we celebrate their 45th year of Independence, telling the story of the rich Pan-African origins of Surinamese music shaped in the hearth of political turmoil.

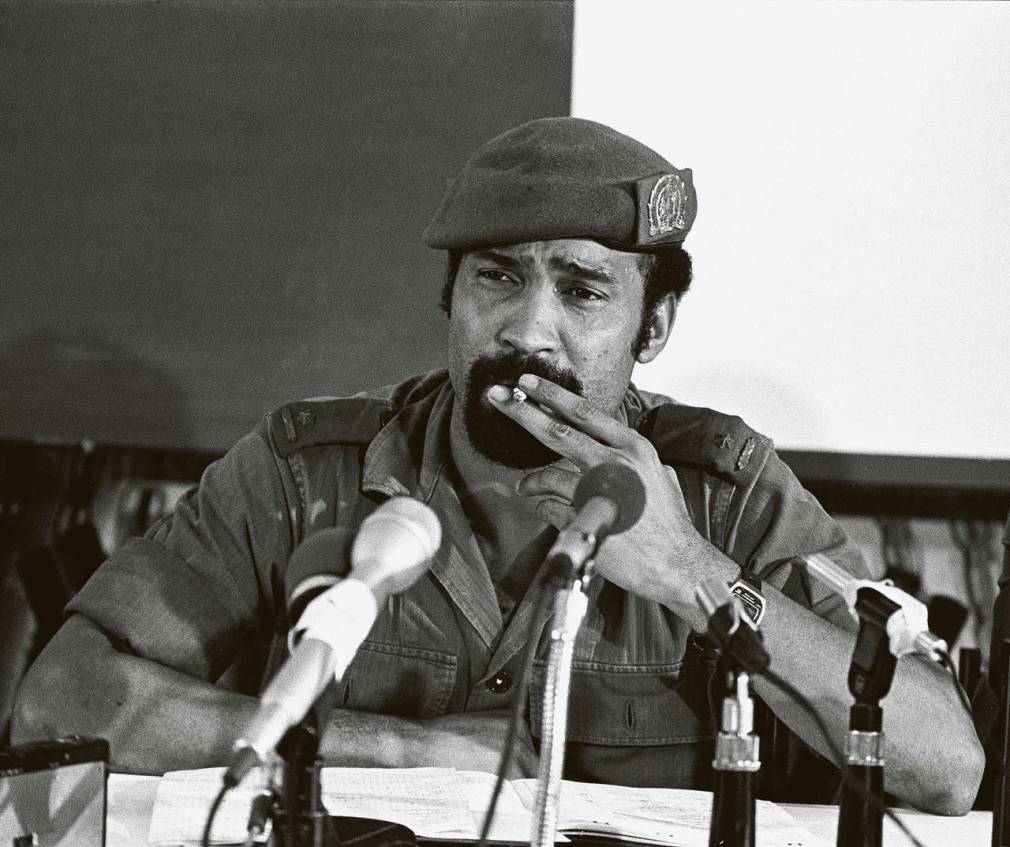

A culmination of political windfall has struck the country of Suriname in recent months. President Dési Bouterse, who had held office since 2010, was found guilty in July 2019 of the murder and execution of 15 political opponents in the aftermath of a 1982 military coup. The trial had been dragging on since 2007 and the ruling, of what are now notoriously referred to as the “December murders”, arrived in the midst of this year’s presidential election. After initial disputes about preliminary results of ballots cast on May 25th, the opposition, the Progressive Reform Party (VHP), came away victorious with former police chief Chan Santokhi at its head. Though no arrests have been made, Bouterse, the 74-year-old politician, faces a potential 20-year prison sentence.

In celebration of this historic victory for the Surinamese people, and in celebration of the country’s original independence day from Dutch colonial rule on November 25, 1975, we want to look into Suriname’s volatile political history and explore how, through the trials of the centuries, Surinamese music has become a symbol of hope, strength, and perseverance.

Suriname, one of South America’s most ethnically diverse countries with over a third of its citizens of Afro-Surinamese origin, is a pan-African focal point. Centuries of colonisation, slavery, exploitation, and independence movements have brought together peoples of many origins, creating a uniquely Surinamese musical identity as rich and diverse as its population. Looking into Suriname’s complicated and difficult history, from colonial imposition to a modern day democratic transition, we note the movements and systems that shaped Suriname’s musical landscape.

Kawina, colonialism, and the Maroons

When the Occident reached Surinam in the 17th century it passed between Spanish explorers, English traders and was eventually colonized by the Dutch in 1667. So began the dreadful history of slavery and colonialization during which the Dutch imported nearly 13,000 slaves originating primarily from modern day Ghana.

Over the years, many of these slaves escaped into the dense jungles off the plantations to form a community named the Maroons. According to scholars, “Surinamese Maroons were recognized as the custodians of the most African cultures and musics to have survived in the Americas” (Bilby, 2001). One of the oldest of such musics is kawina. It’s a style of music distinct for it’s heavily percussive ensembles which include “a small bench struck with sticks, hand-held container rattles, timbal membranophones… small double headed drums” (Garland, 1998) and call-and-responsorial singing. The genre gets its name from the Commewijne River Valley near the plantations of old and Maroon tribe settlements.

Kawina is a feature of the winti spiritual practice that developed in Suriname as a fusion of influences from the African continent, among these the Akan-Fanti traditional practices from Ghana and the Fon traditional practices from Dahomey (present day Benin). (Ofusha Johnson).

While kawina has a history dating back hundreds of years within the Maroon culture, the kawina we hear today likely took shape in the late 1800s. After the abolition of slavery in 1863, the enduring Maroon communities gathered influences from Creoles and foreign migrant prospectors, adding instruments like the harmonica and clarinet, and introducing European harmonies to the ensembles.

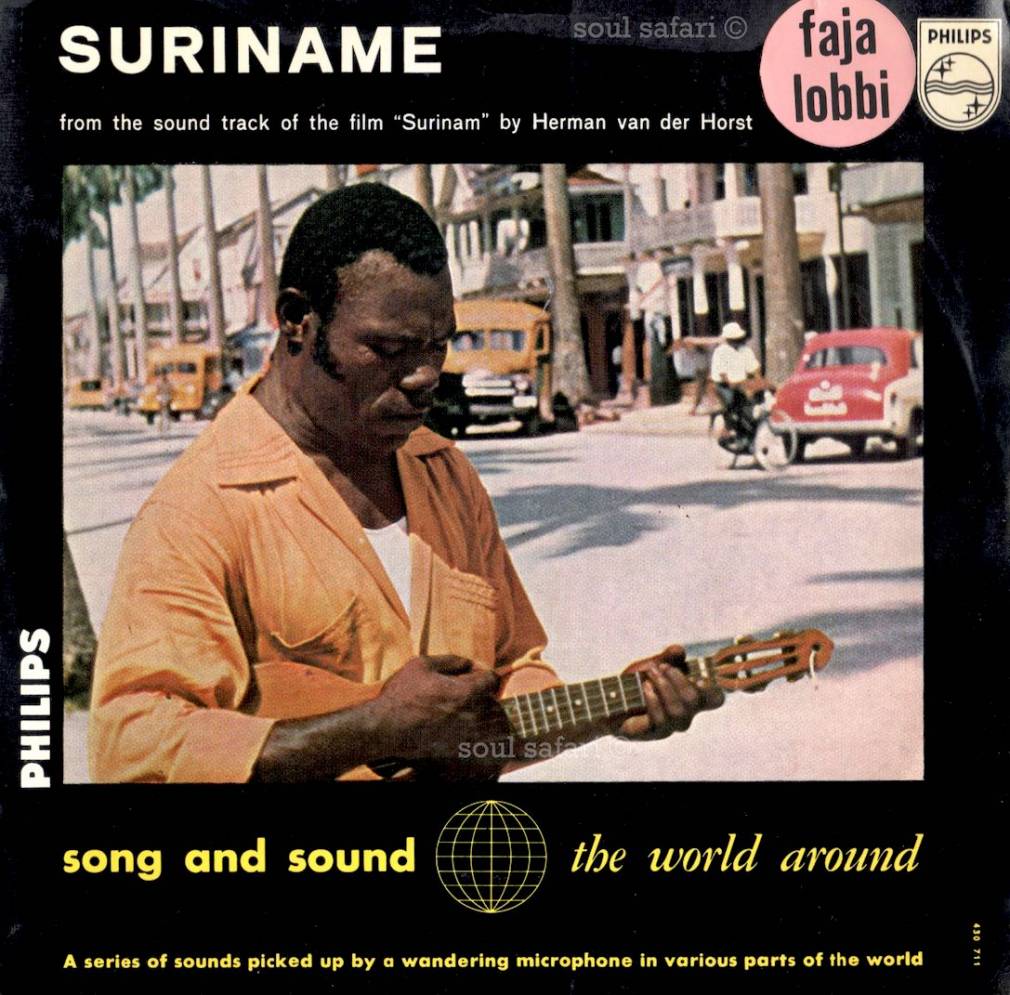

By the mid-20th century, a series of Surinamese icons began recording and distributing kawina music. Marius Liesdek, better known as Big Jones, was the first kawina artist to be recorded on an LP for the Philips Label’s Song And Sound The World Around compilation of the late 1950s. Big Jones and his kawina band were also featured in Dutch documentarian Herman van der Horst 1960’s film Faja Lobbi which matches the iconic track “Ala Pikin Nengre” with shots of Big Jones singing with groups of children in the streets on Paramaribo, Suriname’s capital.

Another forbearer of modern kawina is Johan Zebeda who, as legend has it, saw Big Jones perform when he was a child and decided to pursue a life in music. Zebeda released his full-length kawina album “Tantiri A No Dong” in 1978 with Gemini records. The power of Zebeda’s voice, and preference for a traditional, heavily percussive sound and dry melodies makes for an impressive show of kawina’s power. Zebeda collaborated extensively with the NAKS organisation (Na Afrikan Kulturu fu Sranan), a non-profit dedicated to youth development through cultural preservation. In the 1980s Zebeda joined the Suriname Ministry of Culture with the mission to preserve kawina and winti music as well as Afro-Surinamese culture through education and continued recordings of kawina musicians. At the height of Zebeda’s career, the “guardian of kawina” reached number 1 on the Surinamese charts with the much discussed song “Lena fu Maka Olo”.

More recent examples of kawina are seen in groups like Sukru Sani who made it big with their hit “Pompo Lollipop” in the early 1990s, or the NAKS organisation house group, Naks Kawina Loco, that continues to support musicians who bring the kawina heritage to life.

Kaseko, bauxite, and exploitation

Suriname’s next wave of music came in the twilight of Surinamese independence. The process of independence was long. Beginning with an independent election in 1945, self government under Dutch control in 1954, and full independence negotiations lasting from 1973–1975, Suriname acquired full nation-state status on November 25, 1975.

By this time kawina had mutated into a new genre called “kaseko” which blends Caribbean styles such as calypso, reggae, and zouk with the West African roots of kawina. These adaptations also featured more Western instruments like the trumpet, saxophone, keyboards and electric guitar and bass. The result is a highly danceable sound with traditional African rhythms and Creole flavorings.

The evolution of this fusion can be explained in many ways, but a major factor can be traced to a deal the Dutch government struck with American mineral giant, Alcoa, in 1916.

After a French escapee from the penal colony of Guiana discovered bauxite (the raw material from which aluminium is derived) in the jungles of Suriname in the early 20th century, the country was to be condemned to a 100-year history of economic and ecological exploitation. For 50 years Alcoa mined bauxite from the jungle and sent the metal to be refined abroad by boat. However, in 1958, a trilateral Brokopondo Agreement was struck between Alcoa, the Surinamese president, and the Dutch foreign minister allowing Alcoa to build the Afobaka hydroelectric dam to refine Bauxite on site. The construction of the 1600m² dam displaced “6,000 people living in 43 villages just upstream of the dam” (Pittsburgh Gazette, 2017) primarily of Maroon and Afro-Surinamese descent.

Many of these communities moved to Paramaribo, integrating traditional Maroon cultures with the diverse peoples of Suriname’s capital. Kaseko emerged at almost the same time.

Early forbearers of the sound include the Orchestra Washboard, formed in the 1960s, and releasing Washboard Spirit in 1970 making them perhaps the first kaseko group put to tape. The group was an amalgamation of Surinamese elders and a younger generation influenced by the influx of West Indian indentured laborers, Latin American music, and contemporary pop.

One of the group’s members Lieve Hugo moved on to create a solo project which crystallised the kaseko genre in his 1974 album appropriately named “King of Kasèko”. Like many Surinamese artists of the time, Hugo and his backing group, The Happy Boys, toured the Netherlands and played festivals and clubs throughout Europe.

Another notable Orchestra Washboard member that went on to have a solo career in kaseko was Eddy Felter, better known as singer Mighty Botai. After leaving the original kaseko group, Felter moved to the Netherlands and founded Radio Sranam, a station dedicated to the local Surinamese population. Felter went on to compose 5 albums, one of which played as the soundtrack for Surinamese Independence in 1975, “Independence (Srefidensi) Suriname”.

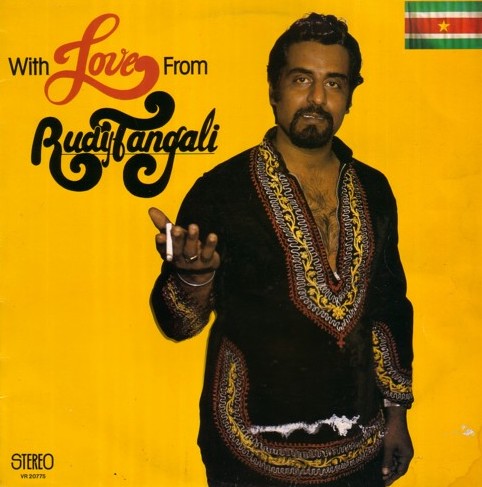

Other prime figures in the evolution of kaseko include Ewald Krolis and Rudy Tangali who made kaseko universal. While Kolis bridges the gap to calypso, merengue, soul and reggae, Tangali made the connection with his Javanese origins, a robust community in Suriname brought in as migrant workers from the Dutch East Indies in the beginning of the 20th century.

While kawina may be Suriname’s first music, kaseko is Suriname’s popular music. Kaseko isn’t bound to a spiritual tradition and is openly interpreted and reimagined by multiple populations across time and despite differences. While it owes its origins to kawina it quickly became the country’s favorite sound that spoke to the people of Paramaribo and beyond.

Funk, independence, and military coups

In the years leading up to Surinamese independence, which was orchestrated by Surinamese-Dutch negotiations beginning in 1974, nearly one-third of the Surinamese population emigrated to the Netherlands. The exodus displayed a lack of confidence in the leading party NPS (National Party of Suriname) and a fear of ethnic degeneration among the diverse groups of the coastal nation.

It was only 3 years after official independence on November 25, 1975 that then military leader Dési Bouterse engaged in a military coup, ordering the assassinations for which he was found guilty in July 2020. Years of corruption and military feuds ensued with Bouterse consolidating power in 1987 by ratifying the constitution to allow him to remain President indefinitely.

As Suriname struggled for its political identity in the face of autocracy, and its people fled to the shores of foreign nations, so did its music reach outward to places like the United States for new influence. The influence is not only heard in the funk and soul stylings of Suriname’s newly emerging funk masters, but is also sung, for the first time, in English.

A note on language in Suriname. While Dutch is the official language of Suriname, the country is home to an astonishing diversity of language and dialects including Chinese, Hindi, Javanese and half a dozen original Creoles. However, it is Sranan Tongo (Suriname Tongue) a language developed by slaves and Maroons in the 17th century, that is most common among Surinamese people. Bouterse himself gained a populous wave of approval by rejecting Dutch outright and speaking Sranan Togno in his speeches and rallies.

Sranan Togno is also the language chosen to sing many of the kawina and kaseko classics. Yet, as American Alcoa engineers poured into the country of roughly 500,000 people, and the newly constructed Afobaka hydroelectric dam provided the electricity for a first wave of televisions and radios in the homes of Surinamese locals, English was soon adopted as the preferred language of funk and soul singers.

Information surrounding the funk Suristars of the time is few and far between. While they leave a legacy of unique grooves that mesh together kawina, kaseko and American Pop, biographical information isn’t so readily available. One thing is known, many of Suriname’s most influential musicians of the 70s and 80s eventually emigrated to the Netherlands.

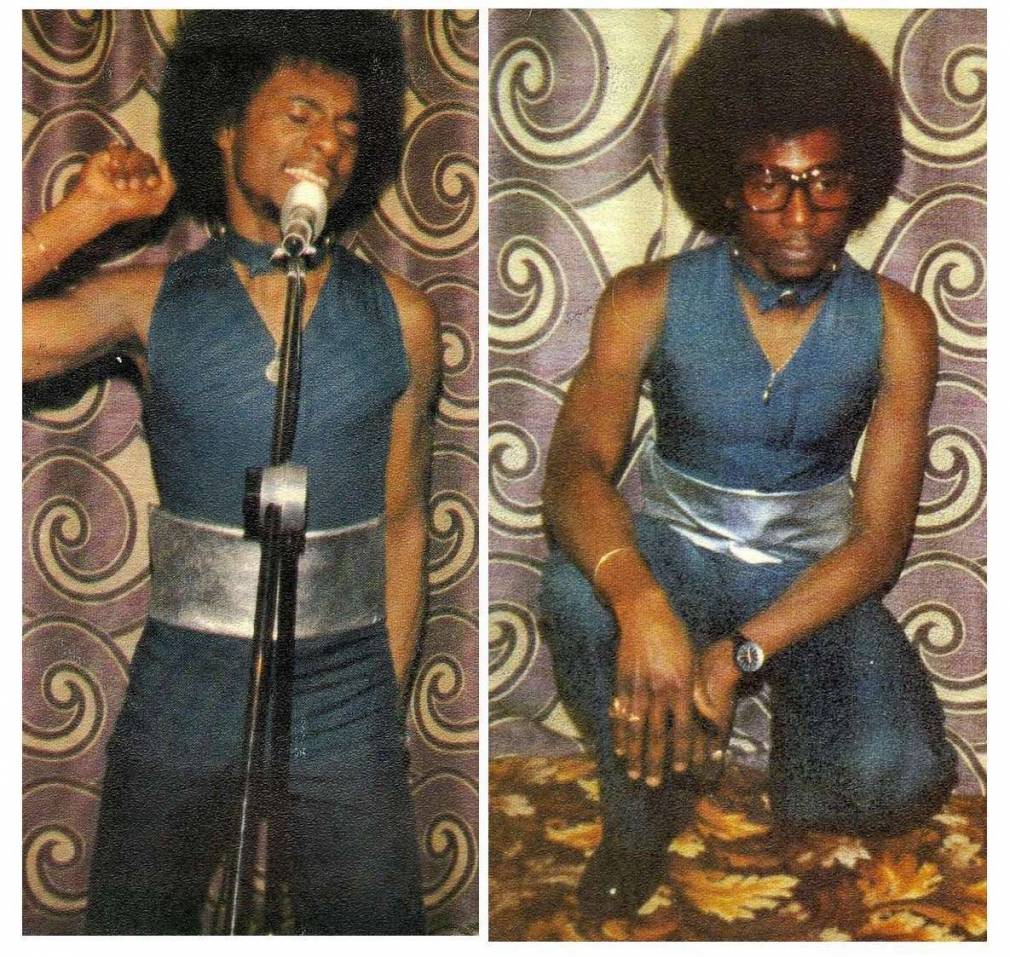

Perhaps the most iconic of the Suristars is Sumy, short for Suriname baby. Sumy had the personality to rival the likes of Prince or James Brown. He famously stated in what seems to be his only recorded interview that he was, “born a superstar, going to the top of the world straight from Surinam” and “the people of Suriname will give me a statue after I am dead because I have proven they can have one superstar child, a main leader forever, ya know?” While Sumy might not have lived up to his own expectations, his debut single “Going Insane” as well as his 1983 album Tryin’ to Survive with tracks like “Bitch, We Danced a Lot” and “Soul With Milk” are on par with funk’s grooviest cuts.

Erwin Bouterse (no relation to Dési) was another Suristar that freely explored the offerings of funk, soul, kaseko and other musics culminating in his Easy To Love LP with his Rhythm Cosmos backup group.

The period also saw kindred spirits of soul music in the likes of Max Nijman a.k.a. “Soulman number one”. Born in the bauxite city of Moengo in 1941, Nijman began singing soul covers of Brook Benton at the young age of 16, likely influenced by the American engineers and Alcoa employees of the region. However, unlike the funk stars of Suriname, Nijman chose to interpret his soul music in Sranan Togno, releasing the album Katibo in 1975 whose titular track is among the most endearing soul cuts this humble author has ever heard.

Surinamese funk saw a modern revival with the Kindred Spirits compilation Surinam Funk Force in 2016 featuring Jam Band 80, Ronald Snijders (who was appointed to the Order of Orange-Nassau for his musical achievements), and of course Sumy himself. As DJs and fans around the world scour vinyl racks for unknown funk and disco licks, the audience for the likes of Sumy and his contemporaries has never been greater. Their sudden re-emergence into the hearts and ears of the modern listener is a testament to their timeless power and wildly bohemian spirit that flies in the face of the autocratic regimes of the day.

Suriname Today

Suriname today seems to be as affected by global music culture as any nation, picking up on the trends of locally adapted hip-hop, dance, and pop music. Artists like Tranga Rugie are putting a Surinamese twist to pop while King Koyeba leads the way with his Surinamese infused reggaeton and afrobeats, both singing in Sranan Tongo. Notable producers like Alfred Bisoina a.k.a. Fredje Studio are also doing their part to preserve the sounds that made Surinamese music unique. An example is Fredje’s Luku Fini Riddim’ project that melded Kaseko with Reggae and Dancehall productions. Nonetheless, it is rap that dominates in today’s music world, and Suriname is no exception. Local rappers like Kiev are racking up millions of streams with clips of life in the streets of Paramaribo.

During the time of Bouterse’s reign, Suriname experienced significant economic compression. Last March the economy nearly collapsed as oil and gold prices dropped. This, coupled with the threat of economic shutdown due to COVID-19, Surinamese banks ran dry and the country was on the brink of defaulting on its debts. These waves of insecurity are nothing new for the 600,000 residents who have endured much since their independence in 1975. Nonetheless, these struggles and its fragile economy have produced less than ideal conditions for the export of Surinamese contemporary music. While many Dutch-Surinamese continue to record music on the European continent, it is difficult to find the edges of a local Surinamese sound into today’s soundscape.

Perhaps the ousting of Dési Bouterse is a pivotal moment in the political and economic future of Suriname, and will eventually create an environment where music can prosper. If Surinamese history has shown us anything, it’s that there is no lack of creative energy pulsing from the tiny coastal nation. Furthermore, the resilience of Suriname and it’s ancestors, in safeguarding their spiritual sounds, collaborating with immigrants of many cultures, and maintaining a flamboyant exuberance in the face of oppression, gives confidence that the history of Surinamese music is far from written.

PAM would like to wish a very special Independence Day to Suriname. We’ll be sure to keep our ear to the ground, anxiously awaiting the next big Suristar for the world to discover.