This is how the story goes – rock and rhythm’n’blues was born in the United States in the mid-1950s between the nimble fingers of Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis, and in the swaying hips of King Elvis and the sonorous voice of Johnny Cash. A story of testosterone and of men, almost all of them white. But what if there were a link missing somewhere in that story? What if history, not always grateful towards women – and especially towards women of colour – had long ignored the crucial legacy of a gospel singer born in the southern United States in the middle of World War I and who, long before her male counterparts, became a guitar hero known for her breathtaking solos? Enter Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915-1973). “She had a major impact on artists such as Elvis Presley. It’s not an image we are used to thinking about when we think about rock’n’roll history, we don’t think about the young black woman behind the white male”, stated Gayle Wald in her comprehensive biography Shout, Sister, Shout in 2008.

Rock’n’Roll: the Rosetta stone de Rosetta

After many years of being eclipsed, the time has come for revival and recognition. In 2018, the prestigious Rock and Roll Hall of Fame finally welcomed the great lady. In love with God and a sense of being free, she re energised gospel music and shook up all convention with her E-sharp solos, her three marriages, and her probable bisexuality.Her complete works have been reissued in France and thanks to the internet other brave and rare gems have also been brought to light once more. Its now possible to see her in a belted dress and headscarf, strumming her Gibson Les Paul in front of a choir on US TV. Or admire her, in the mid-60s, in high heels and a woollen coat, singing her anthem “Didn’t It Rain” at a rather surreal concert on the platform of a disused train station near Manchester in front of a group of young English people. ‘She has a very important place in rock’n’roll because she was always ahead of her time. But her contribution has never been recognised because we tend to focus mainly on men,’ says Jean Buzelin, who has just published a book with the unequivocal title, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, The Woman Who Invented Rock’n’roll.

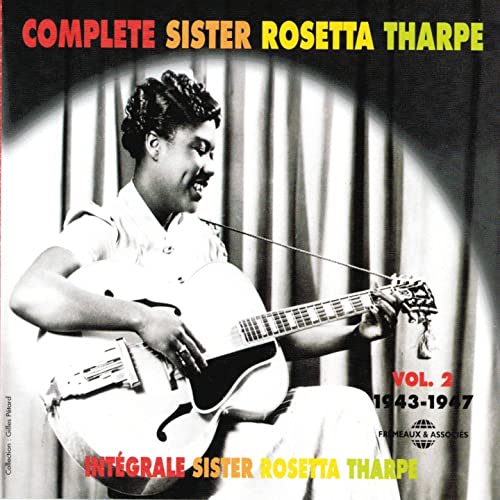

Sister Rosetta Tharpe (who was as much of a “sister” as Ellington was a duke) blossomed in the 1930s and cultivated a clever blend of sacred songs (learnt at an early age in Arkansas’ evangelical churches) and an immoderate love for secular rhythms and smoky cabaret bars. “She discovered that she loved God and the nightclubs,” says her friend Ira Tucker Jr. in a recent BBC documentary about Tharpe. In the then very corseted and segregated American society her sense of freedom wasn’t always well received, but it never got in the way of her success especially in front of the white audience at New York’s mythical Cotton Club. At the end of the 30s, this self-taught artist made her first recordings when she was not even 25 years old, and was rubbing shoulders with the coolest new names on the jazz scene (Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, etc…).Her celebrity was such that she could afford to take a bus with her name emblazoned down the side on a tour to the American South, even as restaurants and hotels were firmly refusing entry to the cotton pickers’ daughter. But it would take more than that to stop her. “She wasn’t a shy girl. She was a fighter, she was rock’n’roll,” says Jean Buzelin.

3 weddings and a funeral

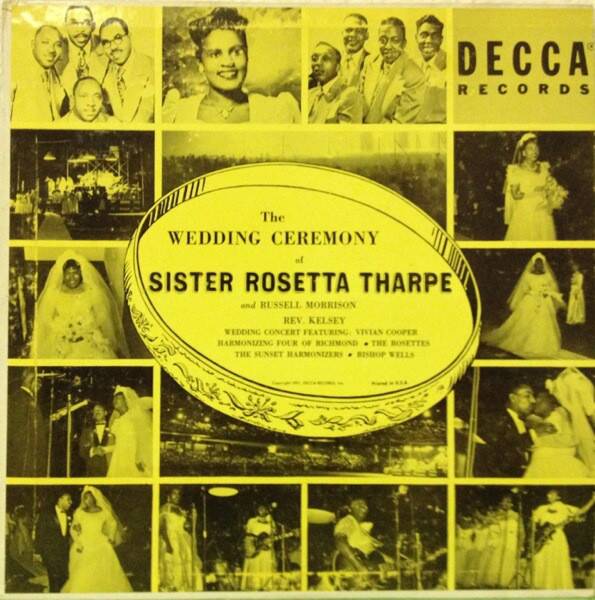

In defiance of the potential danger, she even went on a US tour in the 1940s in a duo with another musician and gospel singer, Marie Knight, with whom she has long been believed to have had a love affair. Hit followed hit (“Up Above My Head”, “Strange Things Happening Every Day”, “Rock Me”) but at the beginning of the 50s, Sister Rosetta had her first flop. In order to relaunch her career, the twice divorcee – who was unattached at the time – launched a, frankly, insane project: to celebrate her third marriage on a baseball field in front of thousands of people and transform the ceremony into a giant concert. Once a suitor had been found, the project became a reality on 3rd July 1951: some 20,000 people snapped up a place at Griffith Stadium in Washington in order to see Sister Rosetta get married followed by a gospel show. It was, according to the newspapers of the time, “the most elaborate wedding ever staged…plus the world’s greatest spiritual concert.”

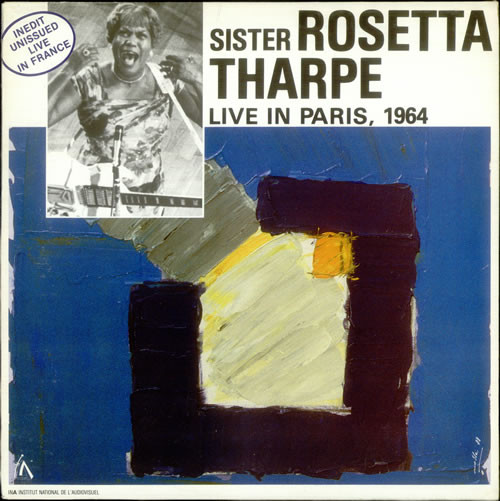

However, this wouldn’t be enough to save her waning popularity. Rock music was gradually being taken over by young white men who would win over listeners with slicked-back hair and unbeatable sex appeal. Abandoned and losing momentum, Rosetta had to move to a small house in Philadelphia with her mother, by whose side she’d stayed ever since they left Arkansas in the early 1920s. However, salvation was to come from Europe. At the invitation of an English trombonist, Sister Rosetta crossed the Atlantic and performed in England and France, including at the Salle Pleyel in Paris. Her odes to God were a little different during the era of protest songs, but they earned her the recognition of the greatest: Bob Dylan would once speak of her in a radio interview, as “sublime and splendid, she was a powerful force of nature”.

The death of her beloved mother in 1968 heralded the beginning of Sister Rosetta’s decline. A few years later she was diagnosed with diabetes and had a leg amputated due to cancer. She passed away in October 1973, anonymously, in the midst of a burst of funk and psychedelic rock. On her grave, somewhat lost in the middle a Philadelphia cemetery, no monument testifies to her place in rock history. Instead, a simple epitaph says it all about the woman who combined the sacred and the profane, prayer and celebration. It reads: “She would sing until you cried and then she would sing until you dance for joy.”