In Utrecht’s Grote Zaal, or “Big Room”, a mass of festival-goers pile into the state-of-the-art concert hall to witness the first European performance of Noori & His Dorpa Band. A group hailing from Port Sudan, it is one of the major highlights of this year’s Le Guess Who? Festival, a yearly event known for its amalgam of innovative talent from around the world. In the massive venue, Noori takes the stage to much applause. Two percussionists, a bassist, guitar player and saxophonist are spread out along the stage. The group slides effortlessly into their brand of Beja groove, a style yet unknown still nostalgic and familiar. Playing their album opener “Jabana”, or “Others”, the musicians bring the international audience together under the hypnotic jams of Noori and his troop. Between tracks Noori smiles and waves, sometimes bowing his head in appreciation of the audience’s loud cheers. At the end of the concert, as the crowd erupts in a standing ovation and as the musicians slowly leave the stage, Noori waits a minute, basking in the limelight, closing his watered eyes to bow.

The next day we meet Noori at Utrecht’s Janskerk cathedral. Slipping into the next room, the colorful soundcheck reverberating in the background for a second performance happening in this new venue tonight, Noori spoke about his life, music and cultural mission. Speaking in his native Arabic, each question provoked long, uninterrupted replies. Often with a smile, a gesture of the hand or a solemn look. Noori tells us the tragic and inspiring story of his Beja people and his life’s mission to preserve and promote his culture’s music in the face of oppression and violence. A story that is as long as it is complex, we spent the next hour recording Noori’s echoed voice in this once sacred place to understand the musician’s long and arduous path.

Noori’s tambo-guitar is born

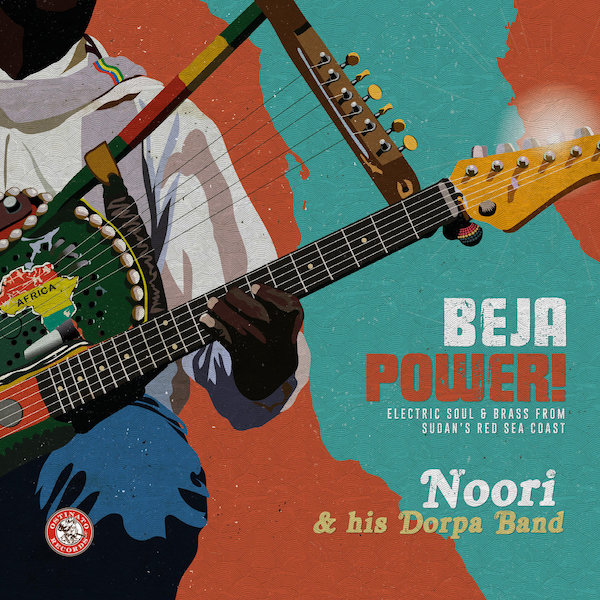

In the early 1990s, in the scrap yards somewhere outside of Port Sudan, a young musician named Noori wandered among the rubble in search of nothing in particular. Somewhere in the debris, Noori spotted the well-preserved neck of an electric guitar. An uncommon instrument in this part of the world. More acquainted with the kissar (a Nubian lyre or tambour) of which Noori’s father was a master, Noori was nonetheless drawn to the instrument. For years the neck sat somewhere among Noori’s affairs gathering dust. Later, when Noori was gifted a vintage 1970s four-string tambour (Sudanese lyre), the musician, capable in welding and tuning, merged the two, making a hybrid, electric, tambo-guitar. A first of its kind. “It is a mix between a Sudanese drum and a guitar,” Noori says in Arabic with a cheeky grin, “I designed it and made it myself.” Seeing Noori with his tambor-guitar today, the soundboard wrapped in cowry shells, the axes painted in the reggae red, yellow, green and the African continent emblazoned in the center, there’s an unmistakable pride in Noori’s creation.

Plucking and composing from the young age of 10, Noori, now well into his mid-life, has merged and preserved more than hardware in his musical career. A member of the Beja tribe, a group historically pushed aside in the name of resources and cultural conformity, Noori’s work has been a mile-marker in the absent history of Beja music recordings. A people with ancestral and often mythological ties to the Nubians and the ancient Kingdom of Kush, the African element of the Beja identity, like the rich deposits of gold in the region, has been a source of wealth and conflict. Though Noori’s father, the tambour player, made good on the transmission of the Beja spirit to young Noori. Drinking from the patrilineal well, Noori was intoxicated with the power of his people’s music. “My father used to play a traditional instrument, the ‘tambur’ or ‘rababa’, I used to watch and listen to him play and that gave me the love of music. When I listen to music, I enter a second state and I feel the need to close my eyes and it takes me to another more spiritual world. It is these influences, these experiences that have inspired me and transmitted this passion for music.” And in this way, the arc of Noori’s destiny was bent towards the Beja musical frequency. History and circumstance would provide the backdrop to this passion.

The Beja’s long act of resistance

An ancient people, the Beja trace their ancestry back millennia. Historians have found linguistic commonalities between the language of the Blemmyes, a tribe of the ancient Kingdom of Kush which reigned the Nile Valley from as far back as 1070 BC. In this Nubian history, the Beja have played a key role, undergoing multiple transformation, conversions and migrations, but dominating the Eastern Desert, a region located between the Nile and the Red Sea, and maintaining control of the area’s abundant gold deposits. While this culture, constantly in flux, emerged as Christian in the 6th Century in the era of Constantine via the influence of missionaries and merchants making their way throughout Afro-Eurasia, the more recent cultural imposition came in the aftermath of the Baqt Treaty; history’s longest lasting peace agreement between the Nubian and Arab ethnic groups. This treaty, which normalized Arab presence in what is modern day Egypt, set the groundwork for Arabisation of the region through commerce, intermarrying and the widespread introduction of the Arabic language.

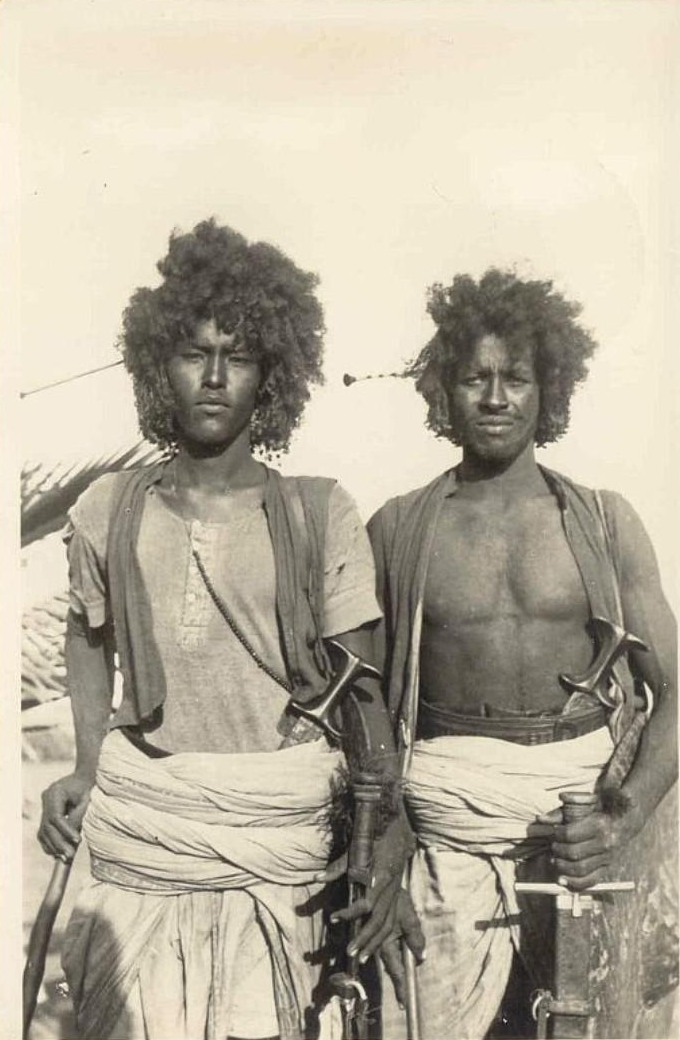

Since, the Beja and its many tribes and subgroups have had a tenuous evolution alongside the Arab world. Despite the nearly complete Islamisation of the Beja by the 15th century, the Beja order fractured into multiple communities that would fight on all sides of the battle lines that were being drawn during the formation of Sudan and the Mahdist conflicts of the late 19th century. While some tribes sided with the Anglo- Egyptian coalition to the North, and another subset with the Italian backed Eritrean forces to the South, the large nomadic subdivision of the Beja, the Hadendoa, made history fighting for a sovereign Sudan. Led by Osman Digna, a self proclaimed Messiah or Mahdi, he and his Beja army wreaked havoc on British attempts to forcibly unify Egypt and Sudan. Osman and the Hadendoa’s efforts were immortalized in the Western world by way of Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Fuzzy Wuzzy” which read; “So ‘ere’s to you, Fuzzy-Wuzzy, at your ‘ome in the Soudan; You’re a pore benighted ‘eathen but a first- class fightin’ man.” Fuzzy Wuzzy, despite being an “abysmal” work of poetry as Christopher Hitchens once said, and being a derogatory slur Rudyard used in reference to the Beja’s tiffa hairstyle, nonetheless praised the Beja resistance for doing what few could, “breaking the square” in the British line of defense.

Though the Mahdist War ended in defeat at the end of the 19th century, the sovereign spirit continued in the Anglo-Egyptian Crown colony and the pressure and dissent from within Sudan (as well as the evolution of domestic Egyptian policy) brought Sudanese independence to a head in 1956. The next year the Beja Congress was formed; a group of Beja intellectuals gathered to defend the interest of the politically and economically marginalized Beja people. This congress fought for the Beja of the Eastern Desert who had historically low rates of representation and less access to education and health services compared to other parts of Sudan. Enduring a series of bans from military juntas and extremist governments, the Beja congress eventually resorted to military interventions along the Khartoum-Port Sudan road, even going so far as to declare a Beja “capital” in Khor Telkok. Canadian academic and journalist for the Sudan Times once noted, “Beja resentment and support for the Beja Congress is clear to anyone spending just a short time in the coffee shops of Port Sudan.” (Young 2007). The relationship between the Beja people, the recently imposed military regime, and the proceeding dictatorship of Omar al-Bashir, all signal a dubious relationship between the ethnic group and the Sudanese powers that be, and are the new front of resistance for the Beja people along with Noori himself.

African identity under an Arab regime

“I was beaten by Omar al-Bashir’s regime. I was subjected to repression and abuse by his security services. They threatened me and imprisoned me several times. The persecution led me to migrate to Egypt, where I practiced my music freely in Egyptian cultural centers and collaborated with Egyptian artists. After eight years, I returned to Sudan and found that the situation was even worse than before—and that we, the Beja people, are still suffering as an artistic community,” Noori wrote in his article published on Africa Is a Country.

The cause for this abuse, while in-part economic and political, also stems from the deep seeded divide of the African and Arab identity. “I am like Othello – Arab-African” says Mustafa Sa’eed, the enigmatic Sudanese intellectual of Tayeb Salih’s landmark novel Season of Migration to the North. “My face is Arab like the desert of the Empty Quarter, while my head is African and teems with a mischievous childishness,” Mustafa concludes in jest, playing on the stereotypical archetypes the West and others have of his ethnic background. This in-between has made the Beja a cultural scapegoat for Omar al-Bashir and other elites looking to impose their conservative order. “He has confused people in order to divide them on their origins” Noori says of Bashir’s ethnic policy, “one is Arab, the other is African, some tribes are better than others, he has plunged people into darkness.” Noori continues on this tense question of Arab-African divide, “the problem in Sudan is that they want to change our African identity to an Arab identity that is not ours.”

Omar al-Bashir ran a political career on marginalizing non-conformist groups within Sudan. From the genocide in Darfur to the imposition of sharia on non-Muslim ethnic groups in South Sudan leading the the Second Sudanese Civil War, (lasting 22 years, from 1983 to 2005, and one of the longest civil conflicts on record) Bashir’s campaign of arabisation also touched the Beja people of the Eastern Desert to Port Sudan, though this imposition received less media attention. “The policy in Sudan has destroyed our heritage, and we have gradually forgotten and lost our African culture,” says Noori, deeply affected by this threat of cultural erasure. “I then understood that I had to have a role as a musician to change this situation, to act for the good of my people.” Noori concludes, “it opened my mind, I started to question the meaning of what I was doing, of the music I was playing, questions I had never asked myself before. I understood that I, as a Sudanese, was part of this culture, of these African rhythms, but our history was dominated and influenced by the Arabs, but I understood that I was African and that even if they tried to change our culture, I remain African.”

Beja Power! on Sudan’s Red Sea Coast

Now, in the aftermath of Bashir and in the face of a newly imposed military government which issued a coup d’etat in October of 2021, Noori and his Dorpa Band are using their music as an act of resistance. The group’s album, released in June of 2022 entitled Beja Power! Electric Soul & Brass from Sudan’s Red Sea Coast is a testament to Beja culture, proudly featuring Noori’s tambo-guitar on the album cover. The 6-track 40 minute album is a smooth introduction to the ancient sounds of the Beja people, sometimes reminiscent of Eritrean funk, other times walking to the tune of Sahel blues always purely original.

“We are musicians,” Noori says of the Beja. “We have been here for centuries between the desert and the red sea with our own traditions and customs that are not found anywhere else in Sudan or in the world.” Nonetheless the sound of Beja Power! speaks of the well traveled meeting-point of Port Sudan along the Red Sea and the confluence of influences that must have merged into Beja music, just as Noori merged his gifted tambour with that of an electric guitar. “Electric soul, blues, jazz, rock, surf, even hints of country, speak fluently to styles and chords that could be Tuareg, Ethiopian, Peruvian or Thai— the world is quite literally housed in Beja music”, writes Ostinato Records, the record label responsible for the album’s release alongside other East African gems like Mogadishu’s Finest: The Al-Uruba Sessions or Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan.

“Our group is composed of musicians from all over Sudan, not only from the east. We met in a music school and we decided that it was our mission to express the richness of the Sudanese traditions that we have inherited through music in order to change the way people look at us,” Noori confirms. “The band has the same spirit and the same problem as Sudan, we feel the suffering of Sudan and this is reflected in our music. I wanted to create the Dorpa band and compose the album Beja Power!, to propose a music that is different from what we do in Khartoum, in the center of the country.” Concluding Noori states, “we have a beautiful and powerful traditional music, we are a peaceful people who have no enemies, we respect the elders, we respect those who respect others, we have a poetic vision of life. As a musician, I feel responsible for conveying a different message, representing our culture and identity and changing perceptions about Sudan.”

And the music goes on…

Finishing his tale in the Janskerk cathedral, Noori thanks us and gives his humble blessing to have his story told. Here at Le Guess Who? his live performance was recorded, and Noori was featured in a film as part of the LGW Embassy: Khartoum, Sudan project. Both are digital totems that will preserve and promote Noori and his Dorpa Band’s work playing the Beja sound. A music that is purely instrumental, it is this act of playing, touring and performing before the world, on the international stage and at home, that is the purest act of resistance. Inside the sunset melodies and the tumbling beats there is a powerful message. A message with meaning often coyly hidden in the track titles like Qwal (“Say”) or Al Amal (“Hope”) or in the bold proclamation of Power! on the album cover. Channeled from the ancient Nubians, inspired by the epochs of religion and migration, and transposed onto the liminal innovation of Noori’s tambo-guitar, this is a music that now has a place in annals of history; a keynote that shimmers like desert gold, pulling the sound away and against the Sudanese shores as the lapping waves of the Red Sea.