Born in Addis Ababa at the end of World War II, Amha Eshèté was never predestined to follow a career in music. Everything changed however in 1969, when the modest record seller dared eventually, to take on the state monopoly of recording and cutting records – and therefore defying “Negus” Haile Selassie I, the Emperor of Ethiopia –, by recording a 45-rpm single of Alèmayèhu Eshèté. Both ran the risk of going to jail for cutting the “double-sided” vinyl in India. “It was the first time you could listen to Ethiopian pop music on vinyl. Even those who didn’t have a turntable bought a copy! The first run sold out in a matter of days,” said Francis Falceto, the sound archaeologist behind the Éthiopiques collection, a series of records that positioned the little-known and mostly fantasized-of country and its African Union headquarters, front-and-center in the music world. In his insanely huge quest to exhume all the treasures of what would soon be known as the “The Golden Years of Ethiopian Music” the French entrepreneur knew from the start that he needed to meet with Amha Eshèté, “THE producer, legendary and unmistakable.” This would eventually happen in Washington, USA, where Amha had gone into exile: it was the beginning of a friendship between two men sharing a profound love of music, a real sense of humor and a pronounced taste for independence. It was through Francis Falceto by the way, that this interview was able to take place in October 2018, meeting up in a hotel car park, a stone’s throw from Addis Ababa’s central square. Let’s roll Amha! For a good two hours, we revisited some of the great milestones in his life. Now in his 70s, his face bearing the marks of time, but with eyes still vivid behind the smoke lens glasses, the timeless elegant Amha Eshèté has not forgotten anything about his crazy years. Ready, set, go…

As a way of starting, there’s nothing quite like going back to the beginning…

I was born in Addis, not far from the high school where my father worked as a civil servant. I grew up in an average social environment, neither disadvantaged nor upper class, and we didn’t want for anything. I was the object of attention, being the only boy with three sisters. I was given nice clothes and sent to good schools, just for being the boy. And then my father was transferred to Harar, before returning to Addis, where I joined the Menelik School. I was a good student, I even skipped a year forward: I should have been proud of it, although I remember it wasn’t always the best situation to be in. You get picked on for any little thing. I got to the point of not wanting to learn anymore, so my dad decided to enrol me in another school. I joined Ethiopia’s best – still to this day: General Wingate Secondary School, which is responsible for training most Ethiopian leaders. You had all the equipment you could dream of there, but there was also a lot of discipline.

Ironically, I was finally able to taste freedom. Looking back, I believe that this was one of the best times of my life. The experience served me for the rest of my life: this is where I acquired my desire for independence and entrepreneurship. Up until my father lost his job, through an unfortunate chain of circumstances. He then found me a winter job – what you would call a “summer job” here – in the State-owned phone company. And what was supposed to last only for the holidays turned into a permanent job. The eighty birrs [Ethiopian currency; translator’s note] a month, I mostly gave to support my family. But the first thing I gifted myself with that money was a stereo turntable, bought second-hand from an African-American who worked at the embassy and was leaving the country. He saw my interest in music, and I got a good bargain. He even gave me some 45s. Soul, doo wop…

Were these your first steps into the world of music?

I had already tried to play the harmonica when I was in high school. I’ve always been very interested in music. I would listen to it anytime I could. But with this new piece of equipment I had acquired, I started looking for all the records that I could. My friends made a habit of coming to my house to listen to music, talk, dance, and have a good time. And then I started frequenting this record store in Piazza [the central square, in the heart of Addis’ redlight district; editor’s note] run by an old Italian guy. We would buy whatever he imported. Two or three birrs for each 45 single, and then he would also give us special discounts. It became my main hobby and I just couldn’t take my mind off it.

And so how were you able to turn this passion into your job?

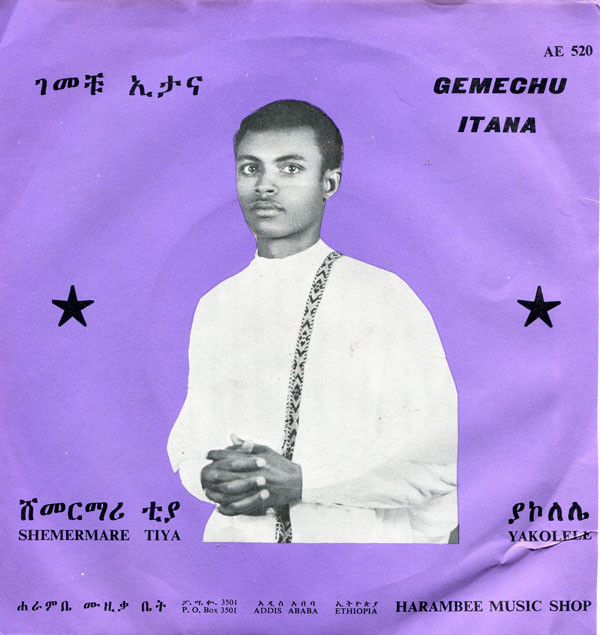

I had worked for the telecom company, the electric power company, then the airline company – roughly five to six-month jobs each time. It changed when I started working with the US Embassy on a cartography mission. It was better paid, and it became easier to order records directly, through a channel that avoided us having to pay customs. I regularly checked out the Billboard charts. I was one of a happy few, a privileged Ethiopian. And on top of that I would sometimes travel to Asmara in a DC3 plane with North American soldiers [*cf. footnote; editor’s note]. It was not that comfortable, but it was free. They even brought me a motorbike back from the US! I was then also working as an accountant in a private club for North Americans in Addis. And that’s how I was able to set up my first record store [“Harambee”; editor’s note].

This is where your legend began. You were importing records that would sell out in a day.

Yes, the whole shop was empty overnight. We only had about twenty copies of each single, and sometimes a few 33-rpm LPs. We couldn’t meet the demand, and that infuriated some people. The younger ones were in major demand of these US-imported 45s. James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave: the big names of the early 1960s. I was almost the only one in the business: there was this store run by an Italian guy, but he was six months late compared to what I was offering.

Soul music was your thing…

Yes: Al Green, Curtis Mayfield, Aretha Franklin, etc. I also liked the blues from the likes of B.B. King, as well as 1940s and ’50s jazz with the big bands. Most of my musical education I learned by ear, listening to the North American radio stations dedicated to GIs. I still listen to radio now: there is nothing better for music, especially given the variety of the current offer.

And soon enough you got the idea to produce records…

Over two, three years, our little business was doing really well. I didn’t have time for anything else. I was importing Indian records, which were really popular here. Once I was able to lay the foundations and be in a more comfortable financial position, I started to think: I’m selling West African and Kenyan music, so why not sell Ethiopian productions too? The big issue: how to get around the state monopoly on music production? When I went to tell them about my project, I remember the people at the National Theater telling me that they were working on the same idea. It would have taken them another twenty years… It was a bluff in fact, but as state administrators they couldn’t admit that they weren’t doing anything for local production. The last record they released dated back to the jubilee of Hailé Sélassié’s twenty-fifth year of reign, in 1955!

So you were turned down but still took the risk to do it…

They showed me an official document, and made it clear to me that it could be very serious if I went against the wishes of the prince – well the emperor – whose word was sacred. What helped me make this wish come true was that I still had all this recklessness in me that my young age excused me for, because otherwise I could have easily just withered away in prison for years. But if I hadn’t done it, who would have dared? Who would have broken this law from a bygone age? It took me several months to think over it, because I could very well have just continued my very successful, yet unsatisfying record store business. It was a difficult decision to make, but it had to be done, regardless of the consequences.

And was it difficult to convince the musicians to break the law?

Very much so! Everytime I would submit a project to singers, they would back away. Playing with our lives was a no-go back then. Even though they didn’t earn much with their work, it was already better than nothing. And I don’t blame them. Alemayehu Eshèté was the first to take the step up. Then he started to convince other musicians: to have a singer was a good start, but having a band to back him up was even better. I myself didn’t have the connections to do the right casting, but he did. He personally knew the right trumpeter, the right saxophonist, the right organist and the right drummer for the project… They were in fact customers of my store, but I hadn’t yet realized their talent.

Selling records and producing them are definitely two different jobs…

We decided to record the first 45s which immediately started a new wave: one side in Amharic, “Timarkialesh”, the other in Sudanese, “Ya Tara” – because Alemayehu was very popular in Sudan too. It was a good compromise, even though we ultimately never exported this record to Sudan. The next problem was that we didn’t have access to a good recording studio. I need to remind you that our references were James Brown and Marvin Gaye! The only place that could offer such standards was the national radio studios. Which is run by the government’s civil servants! The rumor quickly spread that we wanted to make a record in such a fashion, and when we came to request the use of the studio, they already knew everything about our idea. In fact, everyone wanted to do it, but there was no way we could show it to others.

In short, they opened the door for you, but closed their eyes and didn’t want to have anything to do with it…

Exactly. We were able to benefit from the studios without having to say that we came to record music there. Not a single word about it. We cut two sides in three hours! I had arranged beforehand to get a discount on the matrix at a plant based in Beirut. The only thing left was to press the vinyl in India, and to overcome the tariffs of international trade barriers. I had invested money for the entire session, including the musicians’ fees. So when I went to get the records, I was very proud to see my name on them. At the airport, the customs officer asked me if I had been authorised to do all of this, yes, of course, and then went on to ask if I had any copies to give him. Which I did, so then I went straight to my store in Piazza to listen to the record. My return was eagerly anticipated because the rumors had spread in the meantime. As a result, the whole street became blocked off by people dancing to the sounds of our music – with this very catchy melody – and cars zigzagging between them! I think I will remember that moment for the rest of my life.

Yet the police did not intervene…

I’m not sure they even knew about this ban on musical recordings, but the police didn’t care at all. Still, I had already completed the most difficult part of the project. Because now the next record would be much easier to release. We worked with Alemayehu once again, but since the first record had not been pushed as much as I had wanted in Sudan, I thought we should try to include a B-side sung in English: “Honey Baby”, an original composition that didn’t work out as expected either. We were young and enthusiastic, we thought we were living in a dream, which is why we took big risks, production-wise. But I eventually fell in line with the principles of reality, and the following 45s were “100% Ethiopian” songs, although we also released “Mulatu in London” in parallel.

The catalog quickly grew larger…

I soon realized that the people at the National Theater just wanted to a commission: 1 birr for every record I sold. This is what they wanted. But in the end, they offered to receive just 15 cents, and in the end, I never paid them anything. Why would I have done anyway? I just made them wait, and that was it! What helped me the most at the time, and that saved mine and Alemayehu’s lives, was the fact that the political situation was becoming more and more fragile by 1969: the emperor was old and less watchful on all the issues, students were becoming increasingly vindictive, and people were complaining about the cost of living… In short – where uncertainty about the continuation of the regime had started to emerge – it allowed us to do what we wanted. Ten years earlier, it wouldn’t have been the same story at all, believe me.

Was there no censorship at that time?

There still was, of course: the lyrics had to be approved by the authorities, but for this, we weren’t taking any risks. They were mostly love songs. In any case, nothing that would criticize the regime.

And it was like that until 1975 with the arrival of the military junta – the DERG…

Yes, one-hundred-and-two 45s and a dozen LPs in total. But after two years, I was no longer alone in the market: when Philips came to learn that I hadn’t yet been jailed, or even bothered by the regime, they also started producing records. Because of their notoriety, they couldn’t have done it before. On the contrary, I was just a little guy from the underground, who received little attention after all.

You mostly produced records marked by soul, rhythm’n’blues, funk and a kind of jazz. It was about making people dance, while the political situation became more and more tense… How do you explain this paradox?

The nightlife at the time was incredible, as if people were releasing some of their frustration through dancing and drinking. Because we felt the atmosphere deteriorating. You might not believe me: as much as it was difficult to recruit the first musicians to defy the ban, a year and a half later the difficulty was to manage to satisfy everyone who wanted to record! If Philips hadn’t taken over, I don’t know how I would have handled the situation. Every day, I was approached at my store or when I went out to restaurants. I was paying 200 or 300 birr per record, and that was a hell of a fee for a musician. Mahmoud Ahmed, Tlahoun Gèssèss, Seifu Yohannès: there was a lot of talent, and you had to take your time so that everyone could find their own audience. I couldn’t get them all out at once! And then it was a real investment, which you couldn’t lose, especially since I had about twenty people working for me.

During the first sessions you let the musicians do their thing, but then you quickly became an artistic director.

Oh yes, because there were decisions to be made. Both about the repertoire and the musicians. I had acquired enough experience and hindsight to do it: which musician would be best suited to which type of song. I had to learn on the job, and that’s why I’ve always left it to the professionals for procedures that required technical skills, like arrangement.

You have released a number of LPs. How would you choose what to release?

Based on the popularity of the musician. Having a label is a real business. I also released compilations on 45s. I didn’t have the same means as Philips; the banks didn’t trust me enough, and I had to be realistic at times, because I knew I was just a dreamer and a music lover, at heart. Most of the records were printed with 1000 or 2000 copies each. The most was 5000 with Getatchew Kassa’s “Tezeta” 45. And with the hi-fi equipment that we had, the records had to be pressed very well: so many times I heard that Philips’ releases, which had bigger prints than Amha Records, would not even play on record players.

Managing an independent label means being a little bit schizophrenic in a way…

You could say that. I started from scratch as I told you, and I had to help my family. That’s why there was always the risk involved of having to manage a large catalog. All that there is to say is that the label grew until the arrival of DERG [in 1974, overthrowing the regime of Emperor Haile Selassié, who died in 1975; editor’s note]. And there the scenario changed dramatically: with the DERG taking power, they very quickly decided to choose what was important, and clearly music was not to them.

* Asmara is the capital of Eritrea, back then a province under Ethiopian rule, which became independent in 1993. At the time Amha Eshèté refers to, it housed an American military base (after having kicked out the Italian occupier during World War II, the allied troops were stationed in the region for several years under UN mandate).