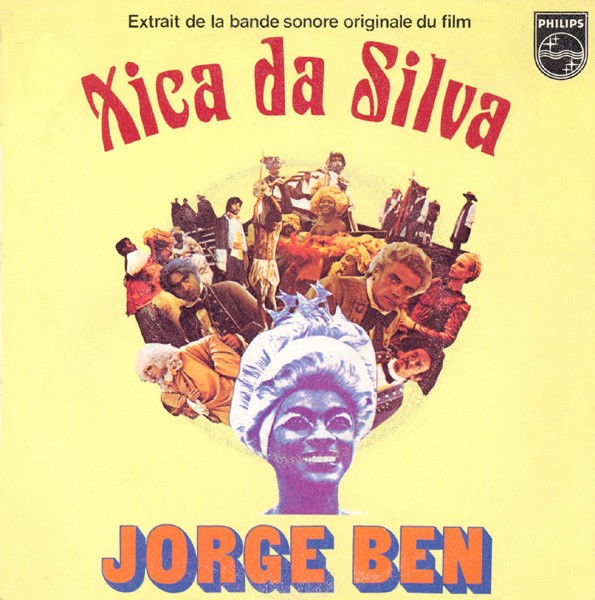

Launched in 1976, África Brasil is Jorge Ben’s most emblematic and acclaimed album. An electrifying fusion of Brazilian sounds, hypnotic Afrobeat and American soul funk, it celebrates Black identity and Afro-Brazilian consciousness. Inspired by a trip to Ethiopia, his mother’s country of origin, Ben recounts the saga of black heroes long ignored in history books, such as the torrid Xica da Silva, first a slave then a woman of power after becoming, in the 18th century, the concubine of João Fernandes, a wealthy dignitary of the regime.

The piece was commissioned by filmmaker Cacá Diegues for his eponymous film, and provides an affectionate, even amorous summary of the festive, tumultuous life of this hyper-sensual Brazilian Cinderella. Using the sound of agogôs and the rolling of atabaques to reproduce the soundscape of the senzala at the time of slavery, Jorge Ben details the character’s environment, repeating almost word for word the film’s introductory text that the director sent him by post. Above all, he underlines the successful emancipation of an exuberant, freedwoman who had to be treated like a queen, and dwells on the image Xica da Silva projected to the nobles and bourgeois of the time: respected, but also envied, feared and hated.

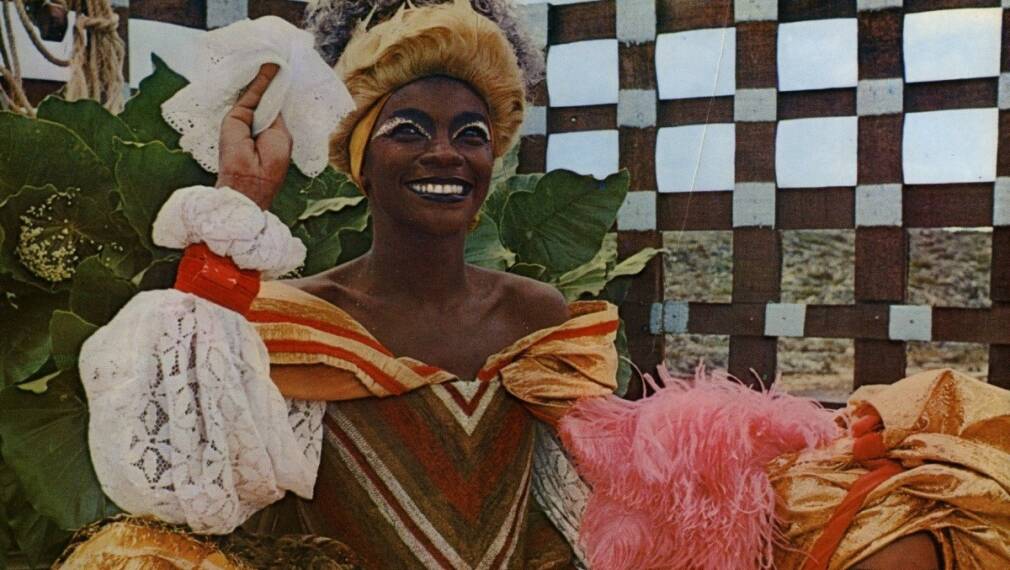

Actress Zézé Motta plays Xica on screen. An icon of black beauty with a warrior’s smile, a muscular body and frizzy hair, she plays a very different character from the slaves in Brazilian cinema, who until then had been portrayed as victims or mothering servants: a seductive, sexually insatiable black woman who chooses her partners and follows through on her desires. A no-holds-barred woman of the 1970s, with a joyful sexuality, who parades down the street in extravagant outfits before the stunned gaze of the locals.

In film and TV: a controversial figure

According to Cacá Diegues, Xica da Silva is not about slavery, but about the right of pleasure. “My wish was to break with the melancholy of my generation and make a political fable“, he wrote in his memoirs. A position criticized by some on the radical left, who considered the depiction of the black slave too equivocal and, above all, too erotic. The latter would have another opportunity to vent their anger a few years later, when 231 episodes of TV Manchete’s telenovela Xica da Silva (broadcast from September 1996 to August 1997), picked up by SBT in 2005, accumulated stereotypes of the lascivious concubine.

In the Brazil of 1976, the story of this interracial scandal and social ascent could only end badly. Since the coup d’état of 1964, the country had been ruled by a military junta, even though serious economic difficulties were forcing it to relax its authoritarian pressure Feminist movements and Black consciousness were only just beginning to emerge, and the evocation of a fleeting experience of liberation in a world of slavery was tolerated. Against this backdrop, the film features a fictional character, the Count of Valadares, hired to restore order to the colony. He forcibly returns João Fernandes to Portugal, and Xica is driven out of town. Morality is saved, but oppression and exploitation take over once again.

Buoyed by its carnivalesque treatment and the charisma of Zézé Motta, Cacá Diegues’ film was a huge success. Poems, novels, children’s books, telenovelas, documentaries and plays all took up the character of Xica. In 1977, Zézé Motta covered Jorge Ben’s song on the B-side of Baba Alapalá (Gilberto Gil), followed the next year by Miriam Makeba, and by the Gilberto Gil/Milton Nascimento duo in 2000. And let’s not forget the disco combo Boney M, who, with original lyrics and music, turned the emancipated Makeba into a spy for those opposed to slavery and racial oppression in the mid-1980s.

Xica, from myth to reality

With Xica da Silva, Brazil rediscovers one of its mythical figures, who became the subject of much research over the years. But who really was Xica da Silva? Thanks to Júnia Ferreira Furtado, professor at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, who published Chica da Silva e o contratador dos diamantes: o outro lado do mito (Chica da Silva and the diamond merchant: the hidden side of the myth) in 2003, we now know a little more about this slave who became a figure of high society. The historian draws on maps, wills, letters, commercial contracts, censuses, emancipations, baptisms and ecclesiastical registers to untangle myth from reality and show how the freed slave used her sexuality instead of armed rebellion to improve her social status.

Francisca da Silva was born around 1730 in the community of Milho Verde, in the state of Minas Gerais, known for its gold, gem and diamond mines, to a white Portuguese father and an African slave mother from Guinea (the Côte de la Mine, now Benin), herself the slave of an ex-slave. She was therefore of mixed race. In 1749, she was sold to Manuel Sardinha, doctor, judge and owner of a gold mine, where she worked as a domestic servant. Two years later, Sardinha, accused of concubinage with three of his slaves, including Chica with whom he had a son, sold her to a priest, José da Silva Oliveira, whose name she kept. He in turn sold Chica to João Fernandes de Oliveira, Governor General of Tejuco (the former name of the Diamantina district), who also owned a gold mine, controlled all diamond extraction and was as rich as the King of Portugal.

In 1753, João Fernandes granted freedom to Chica, who became his concubine, thus acquiring the privileges of Brazil’s white elite. She was 23 years old and spent 17 years of her life at her concubine’s side. With the help of her many slaves, she raised 13 children, including five boys whom she sent to Portugal to study at the schools and universities reserved for whites, and who rose to high social status, becoming judges and officers. All inherited the couple’s immense fortune, as did their sisters, who became nuns or concubines of wealthy Portuguese men.

While the real Chica was prudent in managing her children’s future, she profited handsomely from João Fernandes’ fortune, spending lavishly as the film recounts, and having a sumptuous palace built for herself, with an inland lake carved out of the mountains: “As a freedwoman, she lived in a two-story mansion, owned fine jewelry, a complete wardrobe, with cape, silk shoes and high hats,” says Júnia Ferreira Furtado. “She had 104 slaves for domestic work, cattle breeding, agriculture and mining.” So much so, that she is nicknamed Chica-que-manda (Chica who orders), not only by those who take a dim view of this former slave’s inordinate rise, but also by a whole section of the community who, on the contrary, respect her.

The union with the powerful governor effectively allowed Chica to rise socially and gain privileges. These included attending churches and religious brotherhoods that supported people of color. Although she herself owned many slaves, both black and mixed-race, she granted them certain freedoms (baptisms, marriages, Christian burials and emancipations), made donations to religious orders, organized balls and promoted plays – in short, everything that was expected of a woman of good society at the time.

Contrary to popular belief, the real Chica is no man-eater. She was and remained faithful to João Fernandes until he left for Portugal in 1770 to settle the family estate. He never returned, dying in 1779. Chica outlived him by 17 years, and died in her turn in 1796. Her burial in a white church, with great pomp and ceremony, is the last act of a woman who wanted to integrate into white society and who succeeded, thanks to her perfect mastery of systems of domination, in sustaining power and honor for herself and her descendants.

So where does this myth of the Black woman who conquers her freedom through her ability to seduce and marry the white man come from? The first traces of a manipulative Chica appear in the writings of Joaquim Felício dos Santos, one of her distant descendants, who published Memorias do distrito diamantino (Memoirs of the Diamantina District) in 1868. She is portrayed as a portly, unattractive vixen, brutal, haughty, Machiavellian and capricious, who bewitches a João Fernandes who, like a despot, defies the authorities in the metropolis, until the arrival in the colony of the Count of Valadares, a character totally invented by the author, who brings the governor back into line.

Carnival consecrates the rebel Xica

In 19th-century slave owning Brazil, still resisting abolition, where sexual relations between slaves and white masters were more akin to rape or exploitation, this kind of story is perfectly suited. While Chica’s extraordinary destiny fascinates, she remains the stereotypical sensual, rebellious slave who loses everything and disappears from the colony. In fact, there were many like Chica, former slaves who lived like bourgeoises, blending into white society, married or in concubinage with men of power. Others worked and traded, but Brazilian society succeeded in erasing their memory, leaving only the trace of Chica.

A figure in the national imagination since colonial times, the myth of Chica eventually died out, only to re-emerge almost a century later as a black Chica, seductive and refined in Cécilia Meireles’ collection of poems Romanceiro da Inconfidência, published in 1953, and mixed-race five years later in a play by playwright Antonio Callado. O Tesouro de Chica da Silva valorizes this heroine, victorious over her condition, and makes her a symbol of the fight against racial discrimination.

This is also the point of view adopted by Fernando Pamplona and his partner Arlindo Rodrigues, the set designers of the Rio Acadêmicos do Salgueiro samba school, for their 1963 enredo (theme) devoted to the character of Chica da Silva and based on the writings of Cécilia Meireles. Blackness in the samba enredo is a Salgueiro invention: samba schools have always been a place of black affirmation, but black culture and identity are the hallmarks of the school, which has used this theme in previous parades with Romaria a bahia (1954) Navio negreiro (1957) Quilombo dos Palmares (1960) and Vida e obra de Aleijadinho (1961).

Pamplona is a black intellectual, a professor at the School of Fine Arts and a pioneer of popular culture studies. To illustrate Chica da Silva, he called on Mercedes Baptista for her Afro-style ballet choreography. The first black woman to enter the Municipal Theater, her career was influenced by Abdias Nascimento’s Black Experimental Theater. Isabel Valença, the wife of Salgueiro’s president, plays a black Chica turned Xica, majestic and imposing with her 1.10 m high French nylon wig adorned with semi-precious pearls. Her costume, weighing over 25 kg and studded with sequins and multicolored crystals, cost an arm and a leg. Around her, 12 couples danced the minuet in period costume, while drums resounded. A great show! The audience was delighted, as were the photographers and journalists. The following day, the entire Carioca press was reporting on the story of the beautiful, forgotten black slave and her love affair with João Fernandes. The Salgueiro parade was so memorable, in fact, that no fewer than 12 other samba enredos evoked the myth of Chica da Silva.

In 1963, Acadêmicos do Salgueiro were crowned carnival champions. That year, in Rio, the samba schools paraded for the first time on the wide avenue of President Vargas. In the stands, not far from Kirk Douglas, young Cacá Diegues watches the show. He has just finished making Ganga Zumba, his film about the Palmares epic, a kingdom of maroon slaves that stood up to the Portuguese colonial armies in the 17th century. Enthralled by the first “black is beautiful” in the history of carnival, Cacá Diegues never looked back. Thirteen years later, it’s done, this time on film, to the sound of a heady theme by Jorge Ben. A powerful, radiant Xica, a queen whose name is chanted and repeated as if to recapture the memory of the past, of pre-slavery black civilizations.