Around the ‘70s, there was serious political unrest in Nigeria; a civil war erupted in 1970, leading to a mass murder of several Igbo Christians by Hausa and Fulani Muslims. Back then, Nigeria was culturally and religiously conservative as the nation was ruled by a military, ethno-nationalist government. While the people faced oppression from the ruling political class, the propagation of Christianity in Southern Nigeria resulted in society becoming more conservative. Fuji faced a lot of criticism from these culturally-conservative Christians, mostly belonging to the middle and upper class, who termed the genre local and hooligan. For fuji music listeners who belonged to the lower class in the society, fuji musicians like Ayinde Barrister who used their music to speak against the oppression by the ruling political class became the people’s mouthpiece. Barrister released an album titled Omo Nigeria, where he sang about the political and economic state of the country.

In the mid ‘70s, things started to look up as Nigeria entered its oil boom era, becoming a member of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Though, with the oil boom, wealth was distributed unequally among the elites, creating a larger divide between the upper/middle and lower class, the country recorded an economic boost, improving the socio-economic status of all people. Then, shortly after the civil war, the government took over schools that were historically founded by religious institutions in a bid to make education more secular. All of these combined to propel fuji into the Nigerian mainstream; the elites who benefited from the oil boom hosted regular parties where fuji musicians were invited to perform; with education in Nigeria focusing more on secular ideas than rigid faith-based doctrine, people broke out of the conservatism that bounded them, and were more accepting of fuji music and its Yoruba muslim roots. There was also a respite from military rule between 1979 and 1983 and with the lifting of curfews, people used their newfound freedom to crowd into fuji shows.

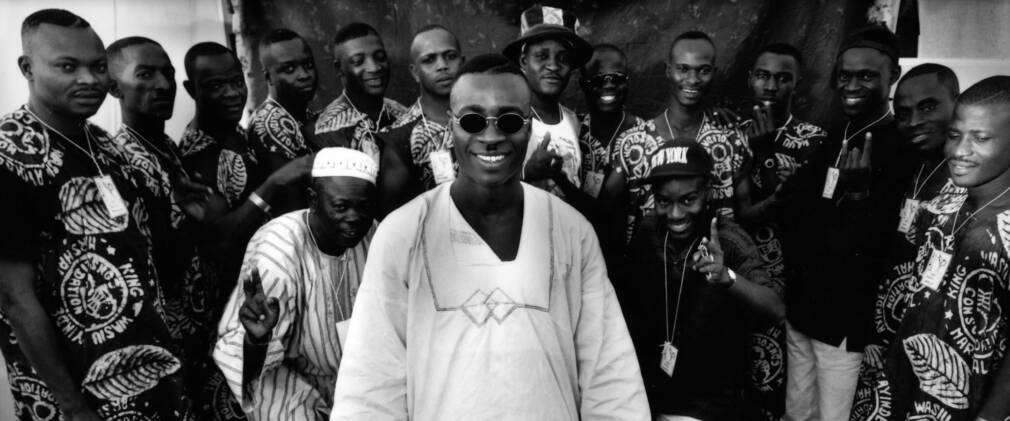

While Barrister and Kollington engaged in musical wars, a young man named Wasiu Ayinde Marshal had begun to carve a path for himself in fuji music. In the mid ‘80s, Wasiu released his critically-acclaimed album titled Talazo ‘84, a refreshing brand of fuji that appealed to socialites in the oil boom era. Before releasing Talazo ‘84, Wasiu Ayinde Marshal was one of the singers in Alhaji Sikiru Ayinde Barrister’s band, initially serving as a roadie under Barrister. Bringing a youthful energy to his style of fuji, Wasiu Ayinde Marshall (popularly known as K1 De Ultimate or Kwam 1) quickly became a pop star, performing mainly to the elites who had just begun to adopt fuji thanks to the singer’s modernised image and style. He excelled particularly in the art of name-praising at his live shows – a core part of Fuji culture – singing praises of affluent people who in turn heaped bank notes upon his head. Wasiu Ayinde Marshal’s style of fuji appealed broadly to younger people as well, introducing instruments like the keyboard and the saxophone to his music, giving his style a westernised touch. Wasiu Ayinde Marshal has often been said to be the most successful fuji musician due to his vast influence on the genre, having pushed fuji to surpass other indigenous genres like Juju or Highlife.

“Wasiu Ayinde was a rockstar. He still is. But back then, he was everywhere,” Billyque, a nightlife promoter and entertainment guru says, “There was no fuji musician as popular as he was. His shows used to be packed full of people. He was instrumental in the middle and upper class embracing fuji.”

After Wasiu Ayinde, a slew of fuji artists rose to prominence in the ‘90s thanks to the genre’s newfound mainstream acceptance. These fuji artists stormed the industry with distinct styles, including Adewale Ayuba whose fuji appealed to energetic youth. Adewale Ayuba was particularly known for his wide-ranging and vibrant fuji sound, which was termed ‘bonsue fuji,’ releasing acclaimed records like Ijo Fuji and Bonsue Tajode. The Fuji act brought a change to the direction of the genre with his “gentleman” approach that manifested in his lyrics, and primarily defined his brand of fuji music, deviating from the violence and rambunctiousness that had long been associated with the genre, and ultimately signing a deal with Sony Music.

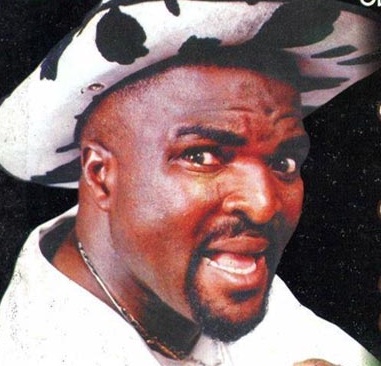

Abass Akande Obesere also popped up on the scene around the same time, introducing a style of fuji known as “asakasa” that was characterised by salacious lyrics in records such as Egungun Be Careful and Asakasa. The elites found Adewale Ayuba’s gentleman style appealing while listeners who hailed from lowbrow areas took more interest in Obesere’s bawdy style. Around that time, contemporary fuji artists like Wasiu Alabi Pasuma, Saheed Osupa, Muri Thunder and Remi Aluko were making their presence known in the fuji music scene. These contemporary acts formed the new generation that revamped the face of fuji music from the late ‘90s into the early and mid ‘00s. Wasiu Ayinde Marshal led the vanguard of fuji musicians that revolutionized the genre, going on extensive international tours to fast-paced cities in the West and spreading the gospel of fuji music globally.