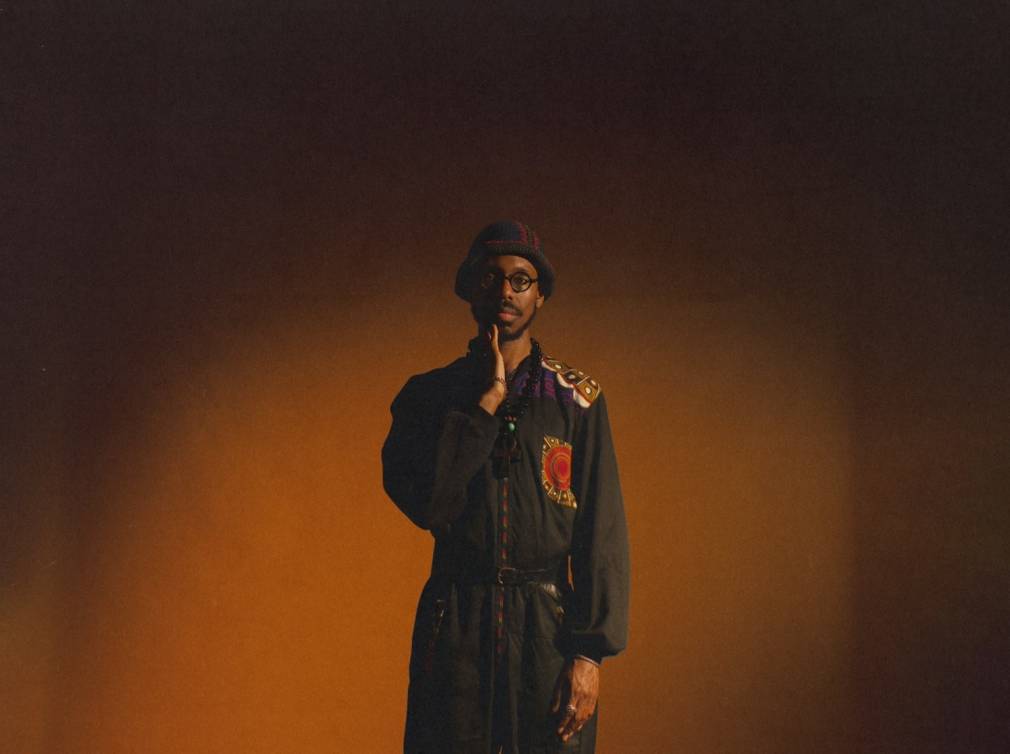

The soon to come new album by Shabaka Hutchings’ Sons of Kemet is a sonic time capsule. A document of the saxophonist’s feelings around the time of the killing of George Floyd and subsequent Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, and a repository of pan-African musical lineages – Hutchings describes the album in a thought provoking essay that will accompany the release as: “a poem for the invocation of power, remembrance and healing.”

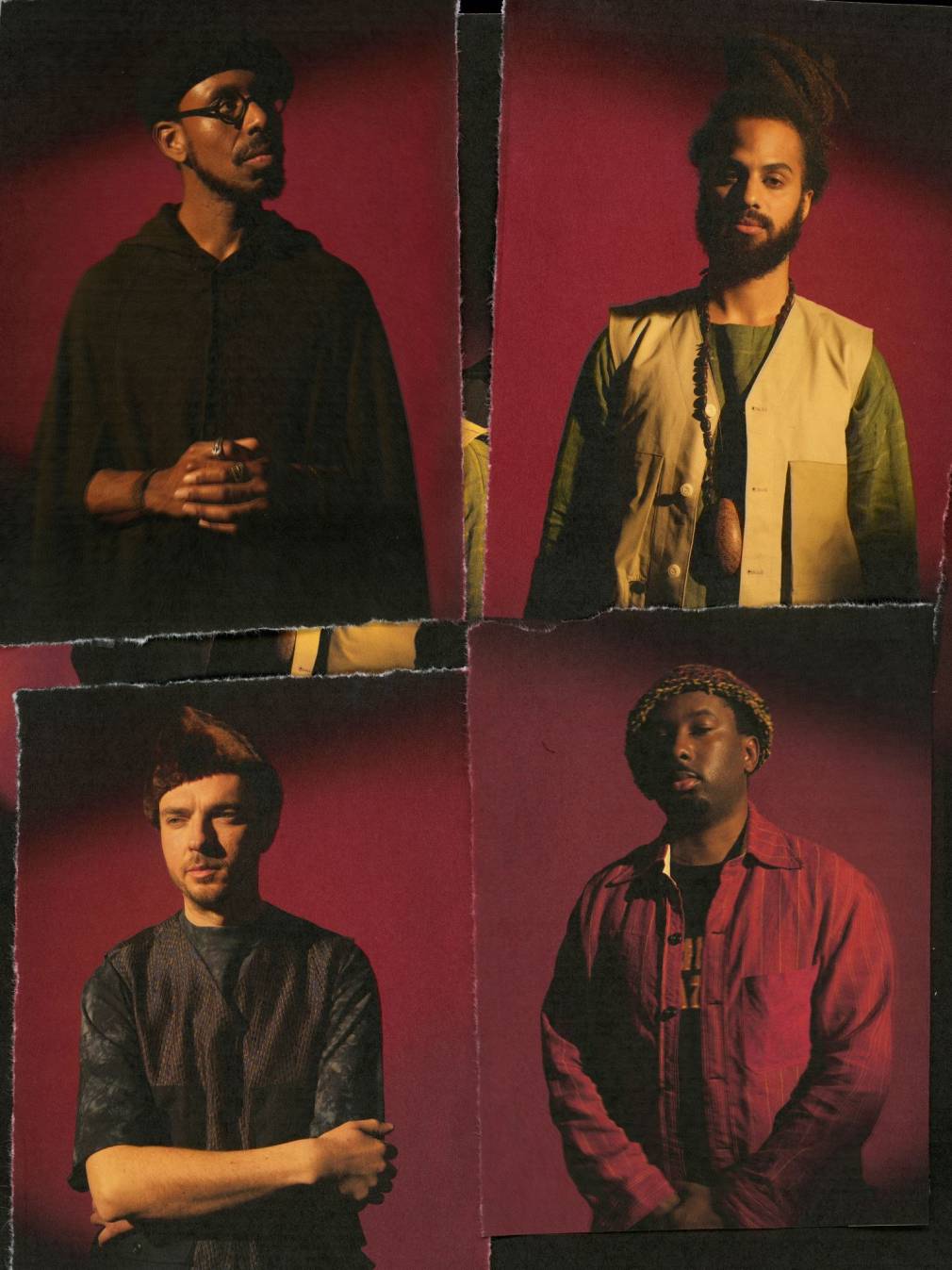

Orchestrated for the four members of this unconventional jazz quartet which is propelled forward by double drummers Edward Wakili-Hick and Tom Skinner and anchored by the steadfast tuba of Theon Cross, Black To The Future is Sons of Kemet’s second album for the legendary Impulse! label and their fourth release since their formation in 2011.

Featuring a number of guests including poet Joshua Idehen, grime elder D Double E and singer-songwriter Lianne La Havas, Black To The Future is a long player crafted in lockdown that is at once futuristic and ancient as we know to expect from a band who take their name from the pre-colonial name for Egypt. Featuring eleven tunes that read top to bottom as one poetic stanza, the album is a meditation on the plurality and commonalities within Black British identity as seen and scored by Hutchings whose cosmopolitan upbringing occurred in London, Barbados and Birmingham.

A voracious reader and collector of sounds and instruments, PAM began the conversation with Shabaka by asking after his current listening and reading.

At our time of speaking what is the last piece of music you’ve had on and the last book you’ve had open?

The last piece of music.. Hmmm what have I been listening to? Actually I compiled a lot of Carribean music I had on my hard drive. A lot of traditional stuff and a lot of tunes I was listening to during the nineties when I was in Barbados. I’ve compiled it on a separate MP3 player so I’ve been listening to lots of Carribean music and I’ve realised there’s a lot in the music that it’s easy to ignore if you just go to other forms of music for what you might consider to be art. So I’ve been asking myself: Do I actually understand Carribean music? Have I gotten the thing behind Soca? How is it constructed? How well do I really know this music that I was brought up with? And the last book I’ve had open? Poetics of relation by Édouard Glissant (Francophone writer, poet, philosopher from Martinique)

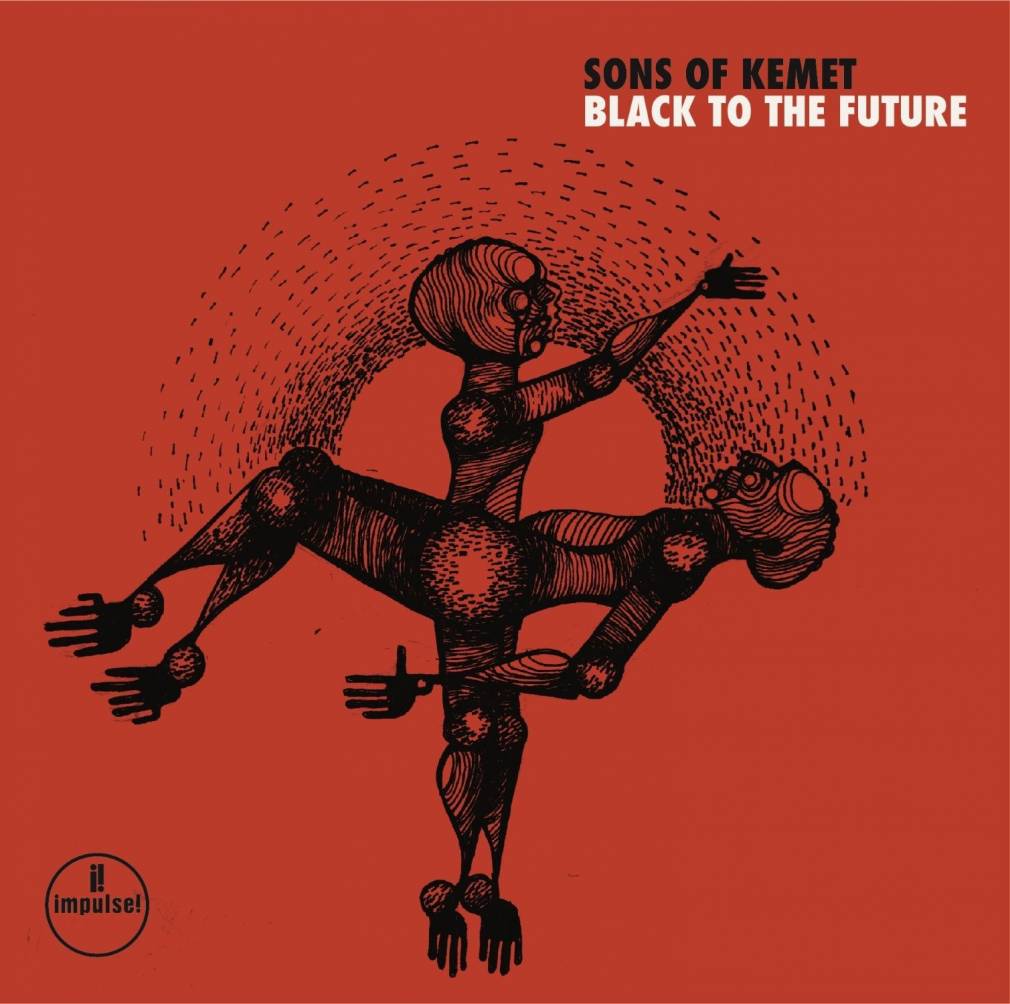

So let’s approach the new record from the outside in. The album’s cover looks like the work of the same artist featured on the cover of Sons of Kemet’s previous album Your queen is a reptile. Who is the artist? And how do you know them?

It’s an artist called Mzwandile Buthelezi from South Africa and I know him from the time I spent in South Africa. He does a lot of albums for the scene of my peers over there and he’s got a really strong spiritual connection with the music. When he does artwork it’s a very intimate collaboration. The creative process doesn’t stop with the music and then the artist does the illustration. It continues until he’s done the artwork and that’s the full stop of the whole process. I don’t like to give him too many ideas before he hears the music, so the thoughts that come into his head and the direction he takes are very intertwined with the music.

On the subject of connections and collaborations, this album features some amazing guests including Joshua Idehen, Kojey Radical and D Double E, how did some of these come about?

With Kojey I’ve been a really big fan of his for a long time. I originally connected with him as I was supposed to play on one of his albums and it didn’t work out for various reasons. But then we collaborated on this tune for the Basquiat exhibition (The Barbican’s Basquiat: “Boom for Real” exhibition in London 2017-2018) So I got in touch with him and asked if he wanted to contribute to the album and he was up for it!

Then with D. we played with him about a month before the recording session for a show at Somerset House and it just instantly clicked. It was like he had kind of always been part of the band! And it’s logical because he’s coming from the same space. So when I hear D Double E, I hear someone who is reflecting what it means to me of the Carribean diaspora within London and to take the essence of the music from the Carribean into the present. It means a lot, as it shows a commonality of approaches that’s not normally acknowledged.

And before we continue to the music within, I want to talk about the essay that accompanies Black To The Future in which you write that the tune “To never forget the source” refers to principles that govern traditional African cosmologies. Would you be able to speak a bit about the specific cultures and beliefs that were on your mind?

The most central one is the idea of the circularity of the journey. The fact that if we consider time to be circular as opposed to linear, if we acknowledge and have reverence for the past and how it is assimilated into the present, a form of momentum into the future is created. An idea of a circularity within time and space that can only be accessed if we really spend time engaging with the past.

There is also the idea of micro cognitivism which is basically the idea that what is reflected on a micro level is also reflected on a macro level. So for instance, if you look at the processes that govern natural cycles, you can find an awareness of the processes that govern human bodily cycles. And if you look deep enough you can see how these processes are mirrored in cosmological and planetary cycles.

And this is at the heart of the Dogon people (of Mali) and how they see that connection between everything, and the symbolism of events, rather than seeing things as being literal and straight forward.

Another idea I found really interesting in the essay was this idea of music being a time traveling vessel. Could you elaborate upon that?

If you think about the sound that you hear when you put on a CD. There is the sound in terms of beats and melodies, but also what you are hearing is the accumulation of certain ideologies, or ideas, and the worldview of the artist manifested in a specific sound. The music you hear doesn’t come out of nowhere, it is from what’s come before, and that’s a form of retention. The academy would like you to think that the only form of retention is in books, or from specific teaching within the walls of the Academy. But there is a lot to be learnt from what is carried on through music and the importance of messages in music.

Listening to the album and reading the press release I was interested to hear that you bring in various flutes and woodwind from Africa and the Carribean. Could you tell me about those instruments and your own introduction to them?

There’s a few on there. We’ve got a traditional flute from Martinique. Then there’s a little flute from Swaziland which I got from the guy on the street when I was there which is a great little flute actually and getting better and better as the years go by. There’s some ocarinas from Mexico, a shakuhachi flute from Japan and even a little bit of recorder on there. And all these extra things were added during lockdown.

The theme I had is of depth. That you have a surface level of anything and then many more layers. So we recorded the album at the end of 2019 and then throughout the lockdown I worked on how I could recontextualise it by adding more elements which is something I’ve not done before.

And what are your plans for involving some of the spoken word elements that are on this record in a live context?

In terms of the spoken word if Joshua can be with us I always like him to be because it’s very important to have him bring that context to the performance. And obviously if Kojey and D Double E are free for the big shows that would be cool. But I am also a really big believer in the album as a document in and of itself and the live performance as something specific, so I’m not really precious about replicating the vocal elements. We are an instrumental band and I don’t want it to be something that gets murky.

Finally, in terms of African music what are you listening to at the moment and what’s your go-to?

In general I like the recordings of Hugh Tracey, the ethnomusicologist who made a lot of recordings in South Africa. Then at the very present moment I’m listening to a lot of amadinda music from Uganda, which is the royal court music from Uganda. It’s a really complex music and I’m trying to understand the sonics of it and what it’s trying to express. I’m also listening to Ongo Trogodé which is Banda music from Central Africa.

For me the music that has been recorded outside of the commercial realm, where someone has taken the microphone to a situation where music is being performed for a function that’s not commercial, rather for a function that is social – that’s what I find the most interesting.

Black To The Future is released on Impulse! on May 14th 2021.

Listen to Sons of Kemet in our Songs of the Week playlist on Spotify and Deezer.