In the early 20th century, when port cities in West Africa thrived, a new indigenous style of music known as palm wine music emerged from the waters. What started out as a form of entertainment in low-class dockside bars where sailors, dock workers, and the working class gathered to drink palm wine, a milky-sweet tree sap alcohol, became a multi-national sensation, birthing local genres across West Africa. Picking up influences and instruments across generations, and reimagined by Ghanaian and Nigerian musical luminaries, the tinny rhymes and cheerful melodies of palm wine would birth maringa, highlife and juju and persist into the music culture of today. This is the complex story of the genre’s humble origins and its massive influence across time and space.

Kru seamen, portuguese guitars and Fante finger-style

The story begins with the faithful old six-string we have come to know and love: the guitar. The indigenisation of the guitar by the Kru seamen of Liberia (also found in Sierra Leone and Gambia), was the first step in the emergence of palm wine across Africa. The Kru people, known for their maritime expertise, were often employed on European sailing ships (starting in the 18th century) to help navigate the West African coast. As history tells it, the Kru people derived their name from westerners who referred to them as members of the ship’s “crew”. Originally from tribes such as the Klao, Bassa, and Grebo, the Kru people were an independent group that westerners were unable to capture into slavery. Instead the fiercely resistant Kru, who often tattooed their forehead and nose to distinguish themselves as free men, were employed for their nautical services. It was during these voyages that the Kru people began learning how to play the portable instruments owned by European sailors including harmonicas, accordions, and especially guitars.

When the Kru seamen stopped at the Gold Coast (present day Ghana), they intermingled with the Fante people who resided on the coastal areas of Accra and Sekondi-Takoradi. There, the Kru picked up the cross-fingering technique from the Fante’s seperewa (a traditional harp-lute) playing, and replicated the finger-style on Portuguese guitars. The Fante people also had a reputation for their traditional percussive style that accompanied their seabound voyages. As the two groups began to combine the Fante’s percussive instruments with the guitars and accordions brought by the Kru sailors, a new genre, known as osibisaaba, emerged.

The Kru sailors continued to journey across different port cities in West Africa, spreading the newly formulated osibisaaba sound, often combined with sea shanties (work songs that accompanied tasks on board). The hybrid sound would rear its head in cities like Freetown and Lagos, as the Kru seamen drank libations with locals, teaching them the two-finger plucking style and chord patterns including “Mainline” and “Dagomba”. Back and forth, land to sea, the songs were carried over waves and coastlines. Many attribute this guitar based, finger-style revolution as a progenitor of genres in places as far as the Congo via rumba-soukous or the makossa of Cameroon. The men and moments lost to the ether, like the soundwaves to the sea, what is certain is the Fante, Kru prototype of machine and mechanism, style and rhythm was ripe for interpretation.

The birth of palm-wine and rise of highlife

Which brings us to palm wine; a variant that gained massive popularity in the 1920s when an unnamed Kru seamen taught this newly-invented technique to Ghanaian guitarist, Kwame Asare (aka Jacob Sam). A massive talent and unrelenting innovator, Kwame invented many styles from this newly opened door. His group, The Kumasi Trio, led by Kwame himself and including H.E Biney (Guitar) and Kwah Kanta (Drums), was renowned for creating classic guitar based, proto-highlife styles including the Yaa Amponsah and the Latin-influenced Dagomba aka “native style”. The trio also has the acclaim of recording what many speculate to be the first official palm wine album, Yaa Amponsah sung in Fante for Zonophone Label in London’s Kingsway Hall in 1928.

While palm wine was beginning to take shape through the influence of Kwame Asare and his Kumasi Trio, the twangy melodies were also making rounds among the Ghanaian social elite. In the 1920s, colonialism was flourishing in Accra. Aristocrats would organise formal dances at ballrooms and nightclubs. Draped in top-hat-and-tails, they enjoyed music played by ballroom and ragtime bands such as Excelsior Orchestra, Jazz Kings, and the Winneba Orchestra. By the early 1920s, these local bands began to infuse their repertoire with the aforementioned osibisaaba rhythms of the Fante people and the emergent styles of Kwame Asare and native style. The fusion was a breath of fresh air for the elites who before then could not dance unchoreographed steps – the music only permitting dances like the waltz, foxtrot, quickstep, tango, and the quadrille.

Though these balls were only attended by the upper-class who could easily afford the hefty entrance fees. Meanwhile the working class was left peering through the windows to spectate on the “high life” happening inside. Nonetheless the more pastoral osibisaaba, native style, palm wine mix continued to gain popularity as local musicians and bands started to perform all over urban spaces and social functions, entertaining Ghanaian professionals including lawyers, engineers, and doctors who were moving from classical music to the new hip sound. Some groups even mixed the palm wine style of Kwame and re-introduced the Akan seperewa into the mix. A “return to the source” that would be christened “native blues”. From the 1930s to the late 1940s, record labels, including His Master’s Voice (HMV) and Parlophone Records, distributed several native blues albums by artists such as Jacob Sam, Osei Bonsu, Kwesi Pepera, and many more which reached the colonial diaspora and beyond.

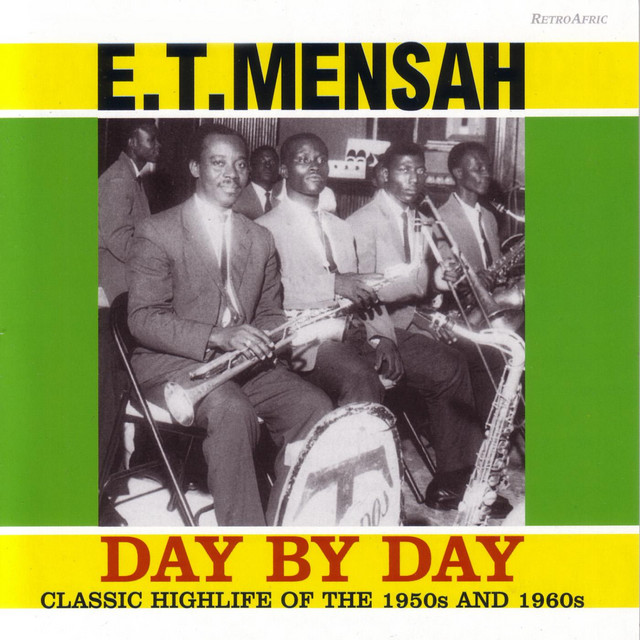

By the end of World War II, the production of native blues records had completely halted, and American and European soldiers who were stationed in Ghana brought with them jazz and swing dancing, forming the Tempos Band. In 1947, a young man named E.T Mensah joined the Tempos Band, and immediately rose to become the band’s leader and once again reimagine the palm wine style. This time with the big band sound that would come to define second generation highlife. As Mensah promoted dance band highlife through extensive touring all over Africa, and the music spread further into urban regions, the guitar-based highlife was steadily making a return in rural communities in Ghana by the mid 60s. E.K Nyame and his Akan trio band, for example, brought immense popularity to the guitar-based highlife in Ghana, recording and performing songs including “Bra Ohoho” and “Small Boy” strictly in the native Akan language. Then there’s Nana Ampadu and his African Brothers Band (formed in 1963) who came into the limelight with their traditional highlife style that was centred on the palm wine guitar with songs such as “Oman Bo Adwo” and “Kwabena Amoa”. It seems, in Ghana, that palm wine never ceased to reemerge into the popular sound.

Native blues and Nigerian juju take control

But it was in the form of native blues that palm wine worked its way East into Nigeria, evolving as juju music among the Yoruba people in the southwest, a genre invented and popularised by Tunde King. Fusing the guitar-plucking style and sonic elements of native blues with Yoruba vocal singing, traditional percussion instruments like the juju drums, sekere (gourd), and a combination of mandolin, ukulele and guitar, Tunde King and his band thrilled onlookers in the teeming neighborhood of Saro Town in Lagos Island. While Tunde King gets most of the credit for integrating the palm wine guitar to form juju music, there were other notable names including Irewolede Denge, Ayinde Bakare, Ambrose Campbell, and Julius Araba who brought their own cup to the juju mix. The Jolly Orchestra, a multi-ethnic band consisting of Yoruba, Ghanaian, and Kru musicians, was especially famous in the old colony of Lagos in the mid 1940s for their groovy version of native blues, rendered in a blend of traditional folk music. A fitting outfit considering palm wine’s diverse origins. All these acts added their respective styles using the palm wine guitar, and released records like Ayinde Bakare’s “Ojowu ‘Binrin” off the Juju Roots album and Ambrose Campbell’s “Ashiko Rhythm” under the HMV record label.

The 60s in Nigeria however was dominated by highlife. Artists such as Rex Lawson and Roy Chicago (known for introducing the talking drum to highlife) were members of Bobby Benson’s big band orchestra and behind hits like “Iyawo Pankeke” and “Ibari Ko Ruwa”. The likes of Bobby Benson and Victor Olaiya made a name for themselves in Nigeria in the late 1950s by replicating E.T Mensah’s sound, recording and performing songs like “Gentleman Bobby” and “Mo fe Muyon”. However, a civil war erupted in 1967 that truncated the proliferation of highlife in Nigeria. Since most popular Nigerian highlife musicians were Igbo people from the South-eastern region of the country, they departed Lagos for their homelands during the Biafra civil war where millions of people died tragically. Igbo highlife artists such as Celestine Ukwu and Osita Osadebe revolutionised highlife in Nigeria by adopting elements from Igbo culture and folklore in their lyrics.

Simultaneously, the decline of Highlife paved the way for juju music which became the go-to music of the Yoruba elites in the 70s, popular in hotels and nightclubs in Lagos and owambe parties in southwestern Nigeria. King Sunny Ade is especially famous for his massive contribution to the proliferation of juju music across the globe, crafting hit records like “Eda Nreti Eleya” and “Awa Arawa”. The palm wine guitar plucking style was central to the development and evolution of the indigenous genre as juju musicians such as Sir Shina Peters and Sunny Okosun who introduced electric guitars to their arrangements.

A brief trip back to Sierra Leone…

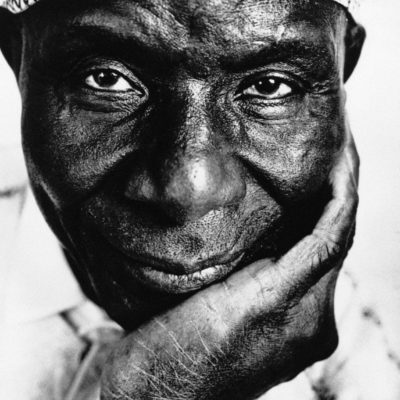

In Sierra Leone, however, though the locals enjoyed listening to Mensah’s big band highlife music and Nigerian juju, they never achieved the same prominence, and were unable to replace the native palm wine guitar band style. The guitar band style, known locally as maringa (a colloquial name for palm wine), was preferred instead. Popularised by creole musician Ebenezer Calendar & His Maringa Band, as well as S.E Rogie in the 1950s and 60s. S.E. Rogie, who would go on to become a kind of West African music ambassador in America, released the album Palm Wine Guitar Music: The 60s Sound as late as 1988. With a career that spanned over 50 years, it wasn’t until later in his repertoire that S.E. Rogie identified his guitar based sound as palm wine rather than the more popular maringa or highlife.

Palm wine lives on

Since its birth in the dingy seaside bars along the West African coast, palm wine and its many forms continue to resonate into the music world of today. Sometimes barely recognizable, palm wine’s musical successors are themselves a blend of many influences. Be it the Americanized Afrobeats, certain hiplife tracks or even the Afropop of Seyi Vibez and Asake. Artists like Show dem Camp in Nigeria have continued to stoke the embers of palm wine music through their music. Show dem Camp, a hip-hop duo that gained prominence in the early days of rap, even hosts an annual Palm Wine Festival that takes place in London, Accra, Abuja, Lagos and New York. The group’s Palm Wine Express album series carries the name in spirit more than sound, but the plucky guitars remain sprinkled throughout. In Ghana The Cavemen. have carried the highlife, palm wine torch forward. On the 2020 album ROOTS we hear the palm wine guitar from the opener “Welcome to the Cave” to hits “Fall” and “Akaraka”. In the Occident, Londonian producer Juls has found a special lane in palm wine music. In September 2023 the artist released his PALMWINE DIARIES VOL. 1 which remains faithful to many elements of the genre including the Fante rhythms and the finger-plucking guitar.

By name or sound, the genre’s legacy is hard to measure. Like many musical evolutions it is non-linear, defies logic and multifaceted. Sometimes it takes local forms, others perhaps, lost at sea. Luminaries and liminal talents create their own form, from Kwame Asare, ET Mensah or S.E. Rogie… Movements in the colonial order or local conflict push it into new spaces, give it a new meaning and fresh sound. Like early ancestors in our evolution, we can look as far as Franco Luambo’s soukous music for a hint of what the common element may be. Often dizzying and complex, it is nonetheless with us, spinning our heads like the milky brew drank by hardened sailors of the early 20th century. But the sound is sweet, the rhythms contagious and the legacy infinite. One thing is sure with the passing of time, palm wine lives on.