Moorish music stands at the crossroads of multiple influences – Sub-Saharan, North African, Middle Eastern and European. It’s a highly sophisticated sound that prides itself in being wholly unique and original.

The music specific to the Moorish Saharan community is considered to be one of the most elaborate and accomplished in the Saharan region. It is referred to as “Moorish classical music”, to denote its erudite nature, based on strict rules in its conception and precise principles when it comes to listening. The height of this artform, aesthetically and socially, was during the Emiral period which preceded colonial expansion in the great Sahara.

A brief history: the origins of Saharan coalescence

So-called “traditional” Moorish music is the Saharan fusion of African and Middle Eastern cultures. It first appeared when the Beni Hassan tribes, originating from the Arabian Peninsula invaded the region. Following their conquest, they soon came to mingle with the Sinhaja; remaining members of the famous Almoravids (whose jurisdiction extended from the Niger and Senegal rivers to Andalusia), to unite today’s progressive and multicultural Mauritania with other ethnic groups – Soninké, Peulh and Bambara. From the 15th century, the Hassan, who had seized political power and were supported by the long-standing savant aristocracy of the Sinhaja people, promoted the emergence of artistic expression combining the use of a new dialect – the Hassaniya – with an extensive knowledge of classical Arabic language and sonic influences from Black cultures. Music came to be the most refined and sublime form of the movement’s productions, possessing the ability to support and legitimize the power of “the new aristocracy” and, furthermore, to enlighten and reflect upon the evolution of a society: that of the Beydhane – the result of a union between the Hassa and the Sinhaja and, on occasion, of Black ethnic groups. This new ethnic composition would give birth to a unique culture in its own right, whose musical and poetic signatures are among the most ethereal in the Saharan region.

Bewitching, exhilarating and fascinating: Mauritanian music knows exactly how to subtly enchant the heart and to get deep inside of it, and then raise the spirit unto its truest form. Both female and male griots possess a true superpower: the ability to “conquer hearts”.

However, this music should not be purely regarded as just a “simple” creation formed by a spontaneous impulse of the imagination, and even less as the fruits of an off-the-cuff improvisation. Quite the opposite! Nonetheless: behind the complex rules of language and metrical composition, what remains in control is the soul; in both a metaphysical and profound sense. In fact, Mauritanian music in its very conception, is based on a “hyper-regulated” doctrine, making for a highly complex and expertly created infrastructure. As a result, it is certainly the most sophisticated and accomplished musical art form in the nomadic Saharan landscape. Therefore, it’s easy to talk of such erudite music, in the “classical” pretence. Its power of expression, eminently visceral, is intimately formed – in its vocal aspect – to the prosody of classical Arabic language and its instrumental nature via sub-Saharan Africa.

African influences

If the rules of versification in Mauritanian music are Arabic, its instruments are most definitely that of an Arab-African nature. First and foremost, we have the tidinit, the main instrument that forms the foundation of all theory in this music. It is sometimes presented (by certain Moors) as a variation of the Arabic oud. But this four or five-string lute, whose wooden sound box is covered with stretched animal skin, is a fairly common instrument in many West African countries (Guinea, Mali, Senegal, Niger, etc.). It is called a ganbare among the Soninké (and was utilised as a weapon of mass-enlightenment by the late Ganda Fadiga as seen in Mauritanian director Ousmane Diagana’s beautiful film Ganda, The Last Griot), a n’goni among the Bambara (played by the late veteran Bazoumana Sissoko, among others). It is also used amongst the Peulh, under the name gaaci. And lastly, the instrument is known as the tehardent amongst the Tuareg people, who played it since at least the 16th century. Incidentally, the Tuaregs are the precursors to the most emblematic of current Kel Tamasheq griots: Amano ag Issa, a pillar of the Tartit group descending from the Timbuktu-based Kel Ansar tribe.

The social stature of the griot, the original master of this lute, varies little from one country to another, or from one ethnic group to another. Their main social function is to create “the defence” via the medium of storytelling to recall historical medieval sagas (accounts of great battles; eulogies; genealogy; and noble human tales of chivalry and morality) of various aristocracies. However, the Moorish griots have a uniqueness which forms their values, and the expression of their art. Perhaps more than those of other communities (having maintained the original function of preserving history through oral traditions), griots are generally and above all well-read scholars, committing their work entirely to poetry. The art of poetry is an everyday activity for griots. They are required to learn it from an early age and to then pass it on to their descendants.

The regulations: channels, modes and sub-modes

Moorish music follows strict regulations, duly thought through and ordered. Its structure is based on “poetic and musical” paths chosen according to the circumstance, the audience and the context in which the music is being played in. For a public performance, the griot generally goes through five modes, each of them having sub-modes (forming a total of twenty-eight), subject to variations – at times very complex. They call it “the Moorish concert”: a musical succession during which the griot performs the different modes by playing in one of the three ways.

The suite is achieved by tuning the lute in a number of ways throughout the concert. The player either loosens the strings or draws them tighter, adjusting the pitch and mood respectively of each song. These sequences, which follow the strict modal progression (from first to fifth) “correspond to notions of ‘darkness’ [blackness] and ‘luminosity’ [whiteness] that transposes the Moorish spirit alongside feelings of joy, sadness, love and nostalgia”, wrote the Mauritanian academic Mohamed Ould Bouleïba, who specialises in studying Saharan and Mauritanian cultures.

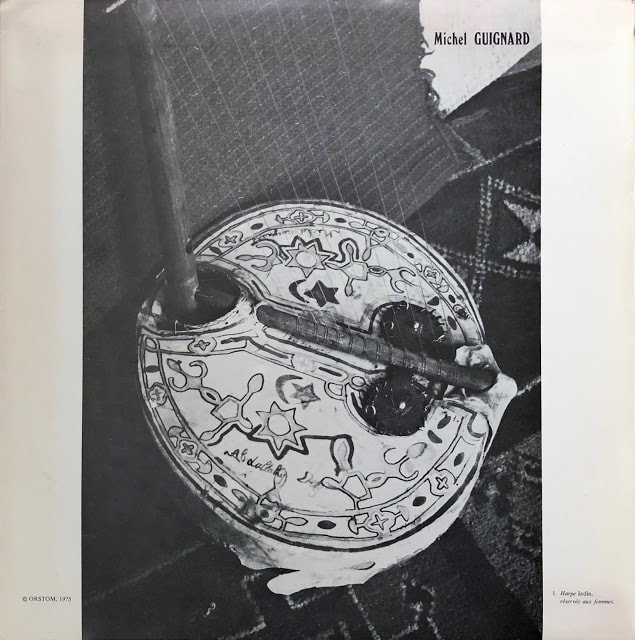

Within this rigorous structure, the tidinit is the lead instrument. The ardine (A Mauritanian harp, aesthetically similar to the Mandingo kora) is played by a female Griot as an accompaniment to the tidinit, along with vocals or rhythmic sections. The griots certainly do not play the songs unplanned; as is the case for any form of classical music, the musicians must follow a pre-narrated order. It flows like a classic story, with a beginning, development in the middle and an end.

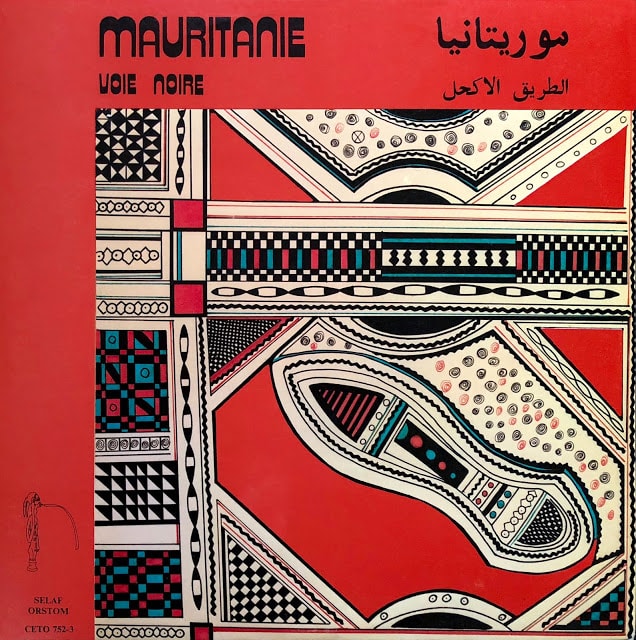

The introduction is made within the “karr” mode, which correlates to elation of the mind: pleasure, joy or even spiritual feelings to generate further enlightenment and good fortune. The griot then switches to “faghu” mode, to recall a historical saga and exalt the honor of the brave and audacious warriors, galvanized by a powerful reflection that “awakens the blood” (Guignard), restores pride and brings about an irrepressible energy to defending a cause righteously. With the third part, the “lekhal” mode, listeners travel through a realm of emotions that get even deeper, and more complex. Then follows the “labyad”, described as being the “white mode”, which is characterized by a certain tenderness, so as to “loosen” the heart. Finally, the concert ends with the “lebteyt”, to express nostalgia and sadness: past joys (love, in particular) and the inevitable end (death).

These different modes (and their sub-modes) come into play in the aforementioned order, according to which one of the famous three paths is chosen: “the white”, “the black”, or the one known as “leg-neydiya”, described as being “the dotted way” by the French specialist Michel Guignard. The term “leg-neydiya” is said to originate from the Soninké culture, according to Ould Bouleïba.

These impenetrable phases form the structure and sequence of the “Moorish concert”. Any composition or score that does not strictly adhere to this regulatory order does not belong to the so-called “classical” framework of this music. Only the great masters, like Elva Ould Abba (Sidaty Ould Abba’s father) manage, through their mastery of these very rules, to improvise a composition and perform it in a “spontaneous” way to the audience, without relying on any written theory or rulebook. Ould Bouleïba points out that “the late Sidaty introduced cultural elements – songs and other lyrical traditions – specific to certain classes occupying the base of the Mauritanian social pyramid“, thus evolving the Moorish concert, from a once very aristocratic affair, towards a wider and more populated audience.

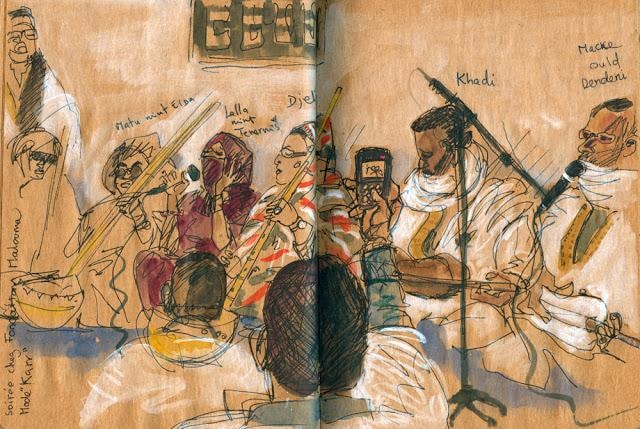

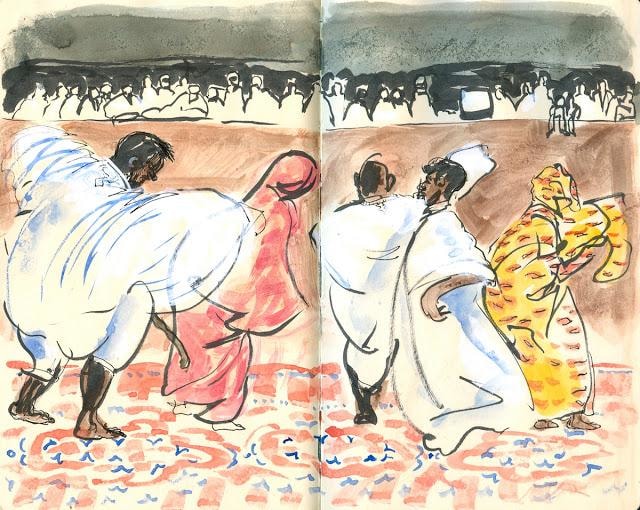

The author would like to thank Isabel for allowing us to use her sketches. Please visit her blog and Instagram profile to see more of her work.