In the second and final part of our introduction to Moorish music, PAM takes a look at how the Moorish sound evolved from the days of colonization. Despite profound upheavals, Moorish music has always adapted alongside new foreign influences. It was able to do so, without losing its spirit, going on to conquer new and greater audiences.

The golden age of Moorish music first came under threat with the colonial invasion of the great desert, in the late 19th century. With colonization being a newly-established system, the regime that had protected the griots until then would eventually collapse. This radical change brought about a certain disdain towards music and it became an art that would experience “(r)evolutions” via the path of globalization and its connection with the outside world, particularly from the second half of the 20th century onwards. However, up until today little has changed and the main zones within the region continue their commitment to the historical poetic and musical culture of the country.

Regional music schools

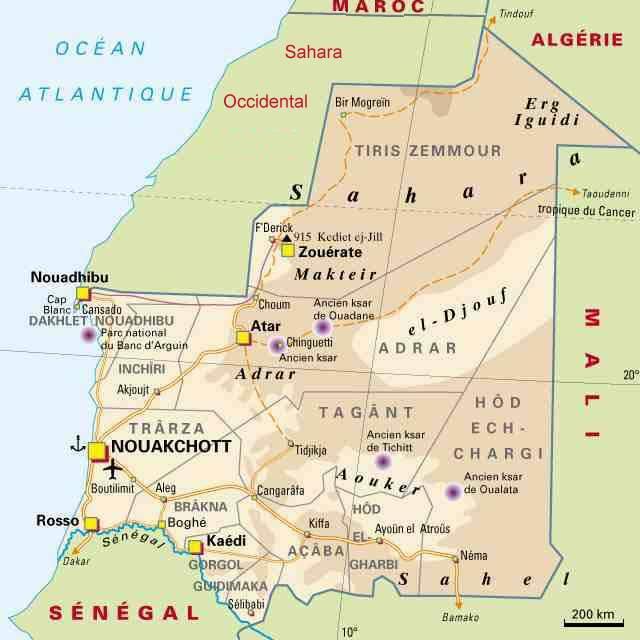

Amongst the vast galaxy of music schools in Mauritania, a number of styles can be identified within them, abundant with regional characteristics – united by both prolific production and consumption of music. There is the el-Howd movement (Eastern Mauritania); the N’djartou school (in the Tagant region) and the el-Gibla (from Trarza to Brakna).

The Eastern school from the el-Howd Echarqi region, neighboring Mali, is renowned for its preference in the predominant use of stringed instruments. The Trarza region is well-known for its very particular emphasis they place in writing lyrics. As for the sounds emanating from the Tagant, they appear, more often, as the middle road, bringing together both of these tendencies.

The intentions of azawan (instrumental preponderance) and al-Hawl (where the poetic intensity of the song is the most powerful part) is to elevate and qualify the families of Mauritanian griots. They can go on to become authors, composers, performers and / or instrumentalists all at the same time. But at times they are solely just the authors of poetry. Their lyrics, sung by others, are passed down from generation to generation, in the same way the great Ehl Heddar family from Trarza did. People even say that “their home is the canvas of poetry”. According to his biographers, Mohamed Ould Heddar (1815-1886), a founder of this lineage, is “the inventor of the concept of Lebteyt in Moorish poetry” [a mode expressing nostalgia and sadness: past joys such as love, and an inevitable death; Editor’s Note]. This history, spanning five generations, and the poetic work of this family have been the subject of extensive editorial and translation works (by authors Abelvetah Alamana and Mick Gewinner), resulting in the publication of the book Le Lignage (“The Lineage”; Ed. Les Trois Acacias, 2016). Below is an excerpt from the book:

As long as I don’t pass too far, and I can still see

The most cherished and beautiful one still sitting there,

I don’t care. And when I say I don’t care…

I mean I really don’t care about anything else.

As long as you whom I love, you smile

And you say what you say…

I really don’t care about anything else.

Mutations, evolution and globalization of the Moorish sound

Following the colonial penetration of the Sahara region, Moorish music has undergone mutations that would only become more apparent further down the line. The Moorish aristocracy swapped places with the new colonial administration. The stature of the “Emir” (the title given to the supreme ruler over a given territory) was reduced to the background, their political power abruptly diminished, or even destroyed. Thus, the influence of the griot, previously upheld by the overlord tribes, was consequently curtailed. In particular, the annual collection of royalties which used to make up the fortune of these tribal lords (these taxes were paid by the tribal fractions, in exchange for protection by a more powerful tribe or for access to pasture areas) would be diverted, taken away from the Emirates back to those of the colonial administration. It was at this stage that the entire Saharan system of the past sank to the bottom of the sea. The old lords, and protectors of the griots, were impoverished and marginalized. And the griots, forced to seek a pittance, would spend less time on their art and the transmission of it to their descendants. But despite all of this, they used their artistic and vocal abilities to raise awareness, and to incite the awakening of these defeated tribes. A classic example of this poetic passion was romanticized in the superb book Le Griot de l’Émir (“The Emir’s griot”, Ed. Elyzad, 2014) by Mauritanian writer Beyrouk. The main character – a griot whose tribe has fallen – refuses to accept the decline of his people, and uses all of his abilities and his art – his verbs, his poetry and the sound of his lute – to awaken and invigorate them. This precisely, is the very function of the griot.

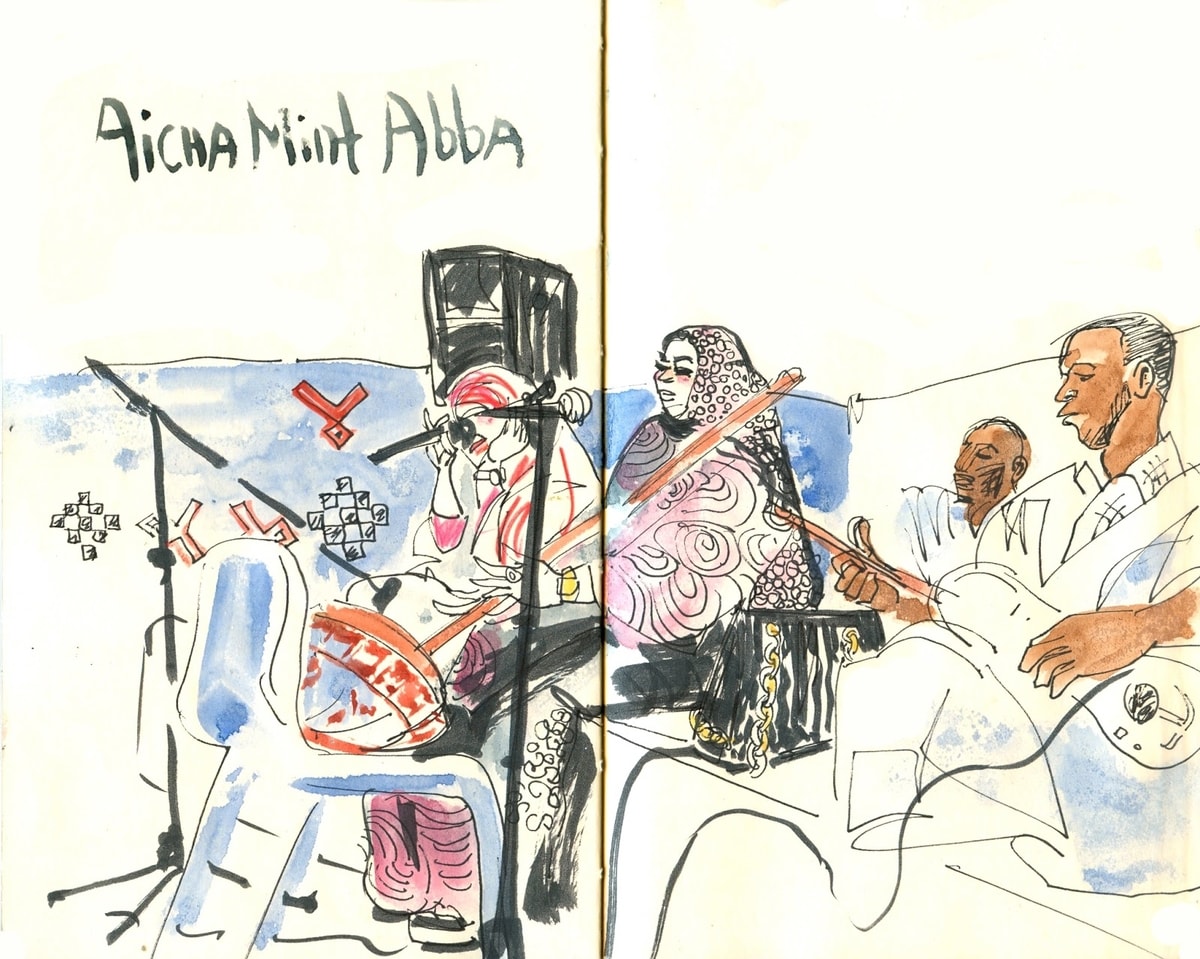

However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that the genre experienced a new lease of life. New media platforms began to promote it and in turn grow its audience, “however the circle of connoisseurs diminished,” wrote the Mauritanian academic Ould Bouleïba. With the help of globalization, a decade later, the art form that was once the reserve of a group of scholarly upstarts, would go on to become “democratized”, in the same way Maghrebian and Arab music popularized itself, opening itself up to new outside influences. The emergence of the modern guitar (just after the country’s independence in 1960) would “relegate” the tidinit, which of course shook the foundations of Moorish music. Consequently, there was an alteration in the sound, both in its vocals and instrumentals. According to Ould Bouleïba, “by using the guitar, you lose the fundamental notions of ‘whiteness’ and ‘blackness’, as well as the fine nuances that exist between the notes and the ‘lagu’ – the referential note which characterizes the Moorish musical concert .” In the three decades that followed, a whole bunch of new artist-musicians appeared. The “griot” term started to lose popularity, in its traditional understanding, although some still remain committed to the traditional ways of Moorish music. It should be noted that within Saharan societies – perhaps the African ones in general – the notion of the griot at times bears more prestige and consideration than that of the artist themself.

However, in these musical “rearrangements”, the audience, often desiring rhythmic cadences, is well served. Even the ears of the most educated music lover (however perplexed they may be), is able to come to terms with this if the orchestration is conducted tastefully with intelligence, as was the case for the band Ahl Nana in their debut, featuring the late Debya mint Soueid Bouh.

The descendants of the highly talented female violinist, in particular the excellent Yassine Ould Nana (very popular in the ’80s and ’90s alongside her brothers and sisters), later embodied an “innovative” wave of Mauritanian music. Their work adapting the instruments (guitar, piano, violin, etc.) was based on the search for a balance which sought to maintain the classical foundations (through singing in particular). The multiple tones that the Ahl Nana produced illustrate the apex of a “modernist” movement that has run through Mauritanian art for the last fifty years.

Modernization is not an end in itself, but it allows one to find the dialogue and openness necessary for progress to happen, but also, to a certain extent, to preserve this music. Contemporary Mauritanian artists have understood this and have remedied this progression with just the right dosage. One could say that Moorish music, with the strength of its artistic expression, with its at times disturbing emotional depth, with its message and its multicultural influences, will long continue as a definitive and key element of Saharan culture. And all that it is able to offer the rest of the world.

References

– Musique et poésie en Mauritanie (“Music and poetry in Mauritania”) by Mohamed ould Bouleiba ould Ghraab (Ed. Joussour/Ponts, Nouakchott, 2017)

– Le Lignage – Ehel Heddar, cinq générations de poètes mauritaniens (“The Lineage – Ehel Heddar, five generations of Mauritanian poets”), by Abdelvetah Alamana & Mick Gewinner (Ed. Les Trois Acacias – 2016)

– Le Griot de l’Émir (“The Emir’s Griot”) by Beyrouk (Ed. Elyzad – 2014)

– Musique, honneur et plaisir au Sahara : musique et musiciens dans la société maure (“Music, honour and pleasure in Sahara: music and the musicians of the Moorish society) by Michel Guignard (Geuthner – 2005).