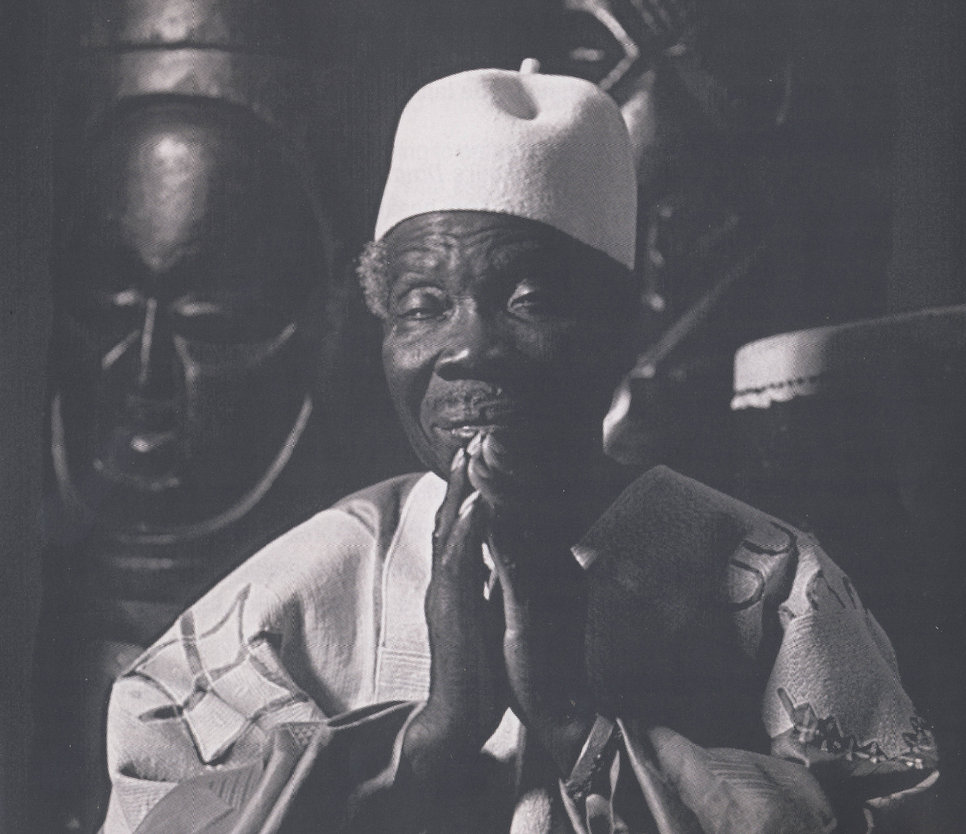

Master drummer, educator, and Pan-Africanist, Olatunji influenced everyone from John Coltrane to Spike Lee in the US where he made his home, whilst in Europe Serge Gainsbourg `borrowed’ Babatunde’s beats for his 1964 long-player Gainsbourg Percussions. Writing in his posthumously published autobiography, the percussionist explained the art of the drummer as; “a very special kind of trinity” comprising the spirit of the tree from which the drum is carved, the life force of the animal whose hide becomes a drum skin, and the spirit of the percussionist. Together these three amount to; “an irresistible force” and provide “a balance that gives the drum its healing power. So let us look at Olatunji’s life in three acts as we pay tribute to the man.

The village child

As origin stories go, Olatunji’s is suitably Homeric. Born in 1927 in the small fishing village of Ajido some forty miles from Lagos, he received the name Babatunde meaning ‘father has returned’ as he was born two months after his father (a chief in waiting) passed. As such, it was hoped he would take up his father’s position, but instead it would be his mother – a potter by profession, who would determine his course.

Writing in his book The Beat of My Drum Babatunde recounted; “There was no school for drumming. Every child in the village is exposed to drums, dances, and sings… But I went beyond that, I would follow the drummers everywhere. They would go from market to market, from village to village, and I would follow.” Seeing her son’s passion Babatunde’s mother made him his first drum, a clay instrument known as an `apesin’, and his fate was sealed.

Moving to the federal capital as a teen he continued his musical education within the Methodist Church where he was employed as a chorister and accompanist. Coming of age in the capital he happened upon an article in Reader’s Digest magazine for a scholarship to The Morehouse Liberal College of The Arts, a historically Black college in Atlanta, and successfully applied, leaving Nigeria for The United States in 1950.

The pan-Africanist

“They had no concept of Africa” Babatunde would write of this time. Realising the need to educate his peers at Morehouse, Olatunji (who had considered a career as a diplomat before he left Nigeria) lamented; “Africa had given so much to world culture, but they didn’t know it. I would invite them to my room and we would talk about their African heritage.” Forming a drum and dance troupe, he began giving school programs on African performing arts and the transmission of the drum that would be his life’s work began in earnest.

Elected president of the All-African Students’ Union of the Americas, he attended the All African People’s Conference in Accra in 1958 where he rubbed shoulders with WEB DuBois, Kwame Nkrumah and Patrice Lumumba. The same year he connected with Radio City Music Hall arranger Raymond White who invited him to collaborate on a performance at the famed New York music hall. Their “African Drum Fantasy” would play four shows a day, for seven weeks, and it was at one of these performances that Babatunde was spotted by Columbia Records Exec Al Han.

Han immediately signed the young drummer and Babatunde’s Year of Africa began with the release of his debut album Drums of Passion on Columbia Records in February 1960. Featuring Babatunde’s arrangements for an ensemble of drummers and voices, this glorious stereo recording includes a praise song to the orisha Shango set to the trans-Atlantic long bell pattern that would inspire jazz drummers such as Elvin Jones and Art Blakey. The album also yielded the song “Jin-Go-Lo-Ba”, worthy of a deep dive as we will see.

A rhythmic conversation between the mother drum (iya ilu) and the baby drum (omele) which underscore a catchy call and response chant – “Jin-Go Lo-Ba” would be `borrowed’ by Serge Gainsbourg four years later for his record Gainsbourg Percussions appearing under the new title “Marabout.” Gainsbourg also lifted interpolations of “Kiyakiya” and “Akiwowo” from Drums of Passion as well as Miriam Makeba‘s “Umqokozo”. All of this proto-sampling was done without permission and Babtunde was never credited. Then in 1969 Latin rock band Santana covered “Jin-Go-La-Ba” as “Jingo” on their debut self-titled album and Carlos Santana was listed as songwriter even though the song was built entirely around the musical hook of Babatunde’s tune.

Nonetheless Drums of Passion would sell five million copies, and in 2004 was added to the National Recording Registry – an archive of recordings considered; “Culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant to, and/or informing or reflecting life in the United States” where Babatunde’s beats are conserved alongside Martin Luther King’s 1963 “I have a dream” speech. With the release of Drums of Passion Babatunde officially became `hip’ and began a storied career as a sideman (often credited as Michael Olatunji) on the records of Cannonball Adderley, Horace Silver and Max Roach.

Babatunde became a regular at New York’s legendary Birdland club, opening for jazz royalty such as Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Quincy Jones. “We were playing ‘Afro-jazz’ before anybody called it that” Babatunde later pointed out, and it was at Birdland that he became close friends with saxophonist John Coltrane. In 1965 Babatunde and Coltrane established The Olatunji Center for African Culture in Harlem to provide music and dance lessons to children. John Coltrane even gave his final concert there in April 1967 three months before his untimely passing, playing alongside his wife Alice Coltrane and the recently departed Pharoah Sanders.

The Elder

In the final decades of the twentieth century Babatunde led his own troupe “Drums of Passion” featuring his students as well as his daughter Modupe and seven of his grandchildren. He remained relevant, and in 1986 filmmaker Spike Lee included Olatunji’s 1962 tune “Mystery of Love” in his debut film She’s Gotta Have It. Olatunji also collaborated with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart on his Planet Drum album, winning a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album of 1991 – the first year the category existed.

As well as teaching in person, Babatunde appeared on VHS, releasing his instructional video Babatunde Olatunji: African Drumming in 1993 on which he explained his “gun, go do, pa ta” phonetic method. Reflecting on his accessible method of pedagogy, Babatunde modestly said: “It was there all along! It comes from the consonants in the Yoruba language. I didn’t invent the system. I just discovered it.” and indeed Olatunji was a lifelong ambassador for the Yoruba language.

“Anyone who does something so great that he or she can never be forgotten has become an Orisha” he stated in his autobiography, and Babatunde would go to the beyond on April 6th 2003, one day before his 76th birthday. Two years previously he had been inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame alongside early New Orleans drummer Baby Dodds and Armenian cymbal maker Avedis Zildjian. His legacy as an educator continues to be felt.

Introducing the idea of the drum circle as a sacred whole, we leave Babatunde the last word “I am the drum, you are the drum, and we are the drum. Because the whole world revolves in rhythm and everything that we do in life is in rhythm.”